Concorde: Supersonic Dart

On the 40th anniversary of Concorde’s London–New York route opening, we take a look at Peter Marlow’s pictures of the short-lived superfast aviation legend

On November 22, 1977 the Concorde passenger jet opened a London to New York route, cutting the lengthy 8-hour flight in half. In the marginal 3.5 hour journey you could land in one city before you had taken off in another, according to the time difference.

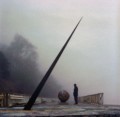

The arrival of the aircraft in 1969 marked the first commercial use of military-grade supersonic technology. Concorde dominated the skies, traveling twice the speed of sound and skimming the edges of the atmosphere. But it wasn’t just the international high-fliers excited by this newfound technology, the general public – who were mostly unable to afford the ticket – embraced the airliner as a symbol of national pride in the feat of engineering, often watching eagerly from the ground.

Yet time eventually caught up with the Concorde, and it was decommissioned in 2003. Even louder than the roar of the aircraft – which shattered windows with ease, much to the vexation of airport neighbors – was the controversy over its high ozone emissions and the subsequent atmospheric pollution. Also weighing the aircraft down was the rising cost of fuel. After the 1973 oil crisis, re-fuelling the Concorde became an expensive exercise, one that could not be sustained.

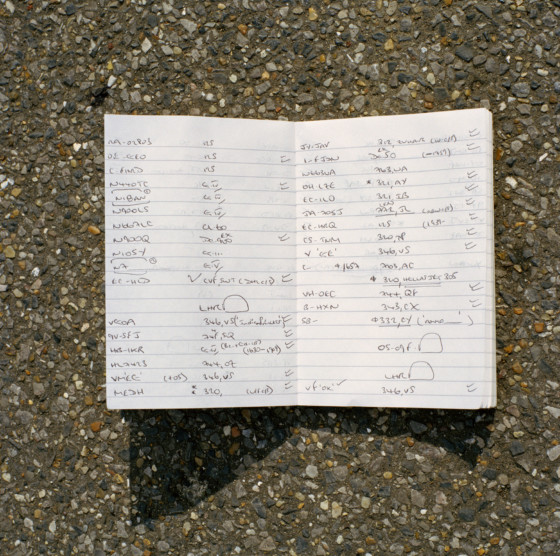

The late Magnum photographer Peter Marlow chose to document Concorde’s final months. In the project, which included a book and an exhibition both titled The Last Summer, Marlow maps the behavior that the iconic jet evoked within the public and the sense of the pathos that settled with the news of its retirement.

"It was only from the outside that you got the true heart-skipping brilliance of this supersonic dart. The journey it made was in our heads."

- A.A Gill

Tracing the aircraft’s flight routes, Marlow found himself in several international airports scouring the fenced perimeters and parking lots photographing ‘spotters’, a diverse group of people united in their love of Concorde; they included an ex-beach bum and a retired grandmother. Marlow soon found his work revealed more about the Concorde from on the ground than the air. In the book’s foreword, the late writer A.A. Gill expands on why:

“It was those on the ground who looked up and felt that moment of weightless awe, and, for a fleeting moment, were once again like a child in bed staring up at Airfix models hanging from the ceiling. They were the real passengers of the Concorde. It was only from the outside that you got the true heart-skipping brilliance of this supersonic dart” adding “the journey it made was in our heads”.

The real attraction of the Concorde was not its luxury status as transport for the elite, but its symbolism. Concorde was a joint venture between France and the UK, with only twenty ever built. When British Airways and Air France both purchased five aircrafts in 1977, it was to the tune of $46 million each. In a century dominated by progressive technological advancements — the Concorde inevitably bolstered national pride for both parties.

The sense of collective sadness at losing the Concorde is palpable within Marlow’s portraits of the spotters, or “armchair Icaruses” as Gill describes them. Every image caption reveals the overwhelming pride and awe the aircraft inspired, with hundreds of bystanders photographed watching its last flights. In one portrait, Geoff Shew, a painter and decorator, laments “It’s sad to see the loss of the last thing that made Britain great”, while Simon Axtem, a systems analyst, simply states “I just wanted to say goodbye”.

"It’s sad to see the loss of the last thing that made Britain great"

- Geoff Shew

"In these quiet elegiac pictures are feelings that can be simultaneously both profound and prosaic, and that’s Peter’s great gift as a photographer….a spotter of the moment between moments"

- A.A Gill

Marlow followed the first Concorde as it was dismantled and shipped down the River Thames to its final resting place at the Museum of Flight in Scotland. As Gill says, “In these quiet elegiac pictures are feelings that can be simultaneously both profound and prosaic, and that’s Peter’s great gift as a photographer….a spotter of the moment between moments”. The project captures how modernity gives way to history in a blink of an eye, while delivering a suitable send-off for the iconic airplane.