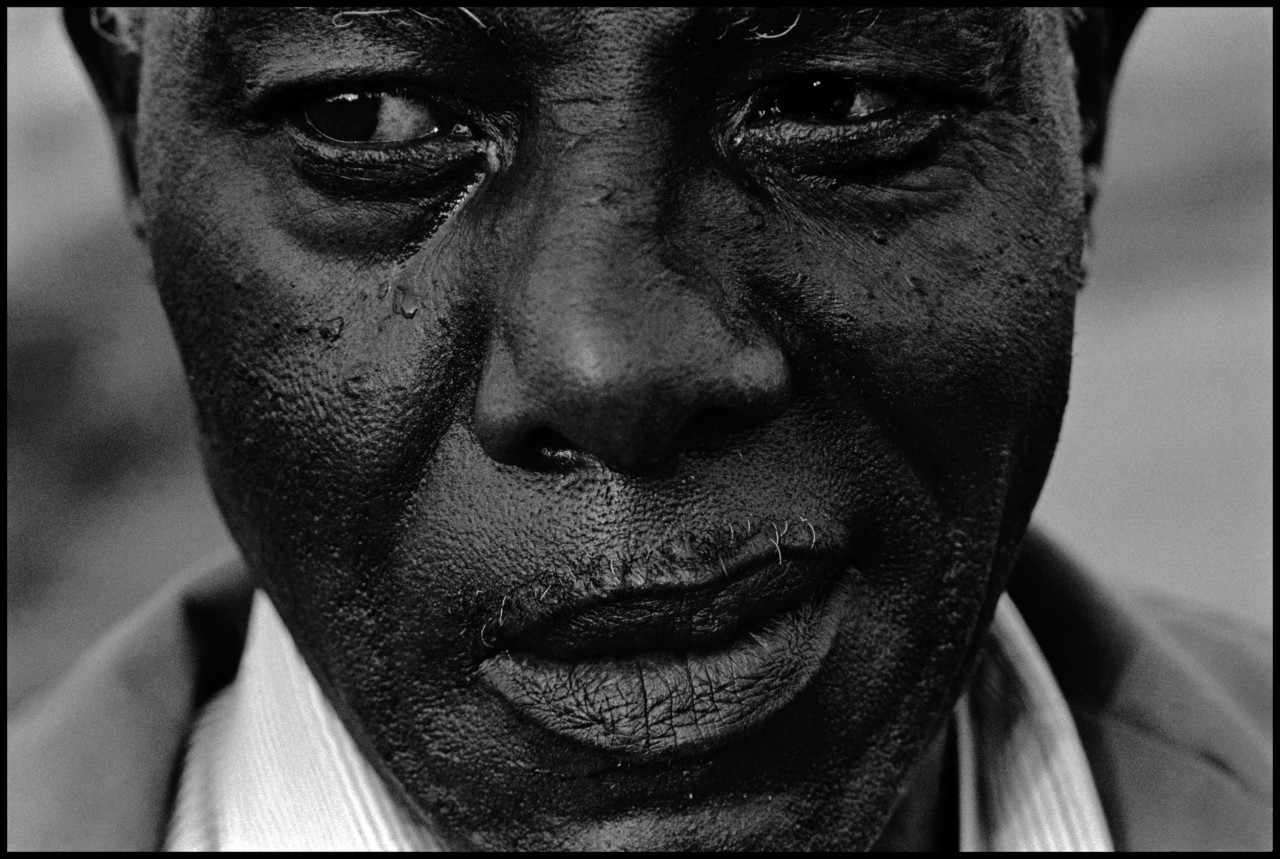

Human Rights at Home: Eli Reed on the Struggle of Black America

The Magnum photographer reflects on his life’s work documenting the daily experience of African Americans

Seventy years ago today, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a milestone document that “proclaimed the inalienable rights which everyone is inherently entitled to as a human being”. To mark this, we explore the way Magnum photographers have reported on injustices in their country of birth. Many have worked on such issues extensively around the world – but how difficult is it to turn one’s gaze inwards and examine the flaws that exist in your own ‘backyard’?

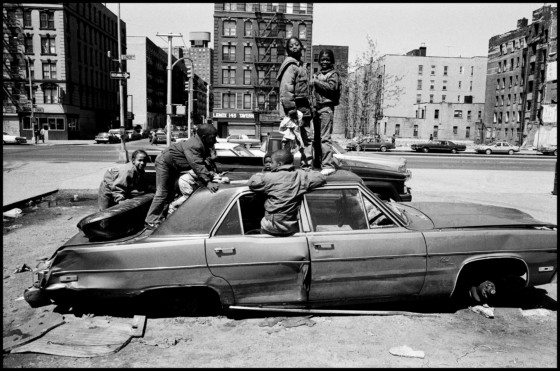

Harlem, NYC, 1970. Eli Reed, then aged 24 and not yet a world-renowned photographer, was circling the streets trying to find a parking spot. A New Jersey local, this was his first time in the Manhattan neighbourhood and he wasn’t entirely confident that his car would still be there when he returned. Reed was on his very first photographic assignment, covering a fundraising concert put on by the Young Lords, a national civil and human rights movement which began in Spanish Harlem.

“The thing started at midnight,” says Reed, reflecting on the electricity of that evening. “The woman—a beautiful black woman who had a big afro—who was MCing, clutched the mic like it was a lifeline and looked at the audience and said; ‘I was told that I should tell some jokes…well I don’t know any jokes.’ She had no jokes to tell because she was so angry! It was a great moment.”

Though Reed had been taking pictures since he was a teenager, he decided to document the experience of black people in America in earnest around 1980, after a crystallising moment with his friend and mentor, Donald Greenhouse. “I was desperate to go photograph in Vietnam. I was going to buy a one way ticket and Donald said: ‘You know there’s a bigger war here at home.’ I said: ‘What do you mean?’ He said: ‘The racism.” Reed has since reported in war zones around the world from Beirut to El Salvador to Haiti but the “disquieting truth back home” remains a painful constant.

Reed’s parents lived through a traumatic time; “struggling for their rights as human beings in the United States”. Reed himself suffered injustices and racial slights growing up, which trickled into his consciousness during his formative years. In Third Grade, when he gave a Valentine’s Day card to a pretty blonde girl, a couple of white boys told him they planned to beat him up. “I was so pissed off,” says Reed. “It didn’t get to that point though – and if it had I would have aggressively defended myself.”

But early experiences like this, though very hurtful, were few when compared to the support he got from his teachers and others around him. “At school, I wasn’t looked down on, I was encouraged,” he adds. “It was not like what was going on in the South, with the Night Riders [KKK members who terrorised black communities] and so on. But there was still this feeling; if you’re white you had this sense of entitlement.”

It was at school that he first realised the power of photography to express injustices. “I took photo illustration design and spent a lot of time looking at photo annuals,” he says. “The images with the word ‘Magnum’ next to them always showed a deeper meaning and were telling the stories that needed to be told. I didn’t even know what Magnum was then but that was my biggest influence; to understand the possibility of saying something.”

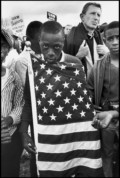

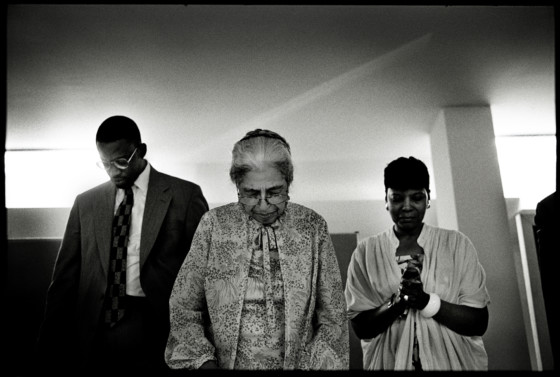

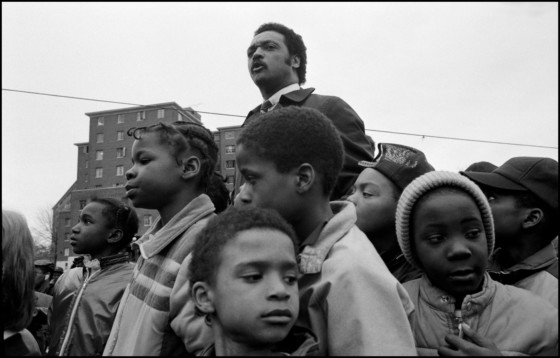

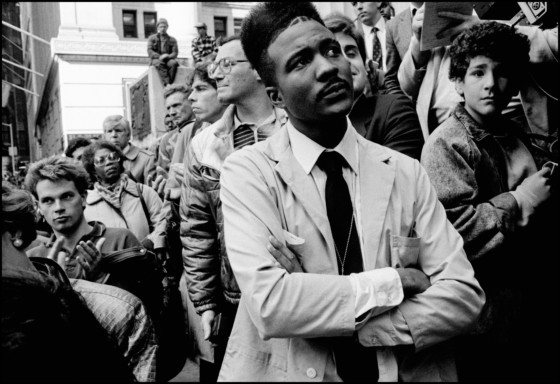

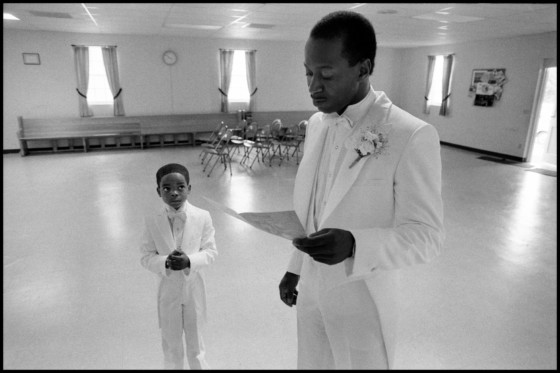

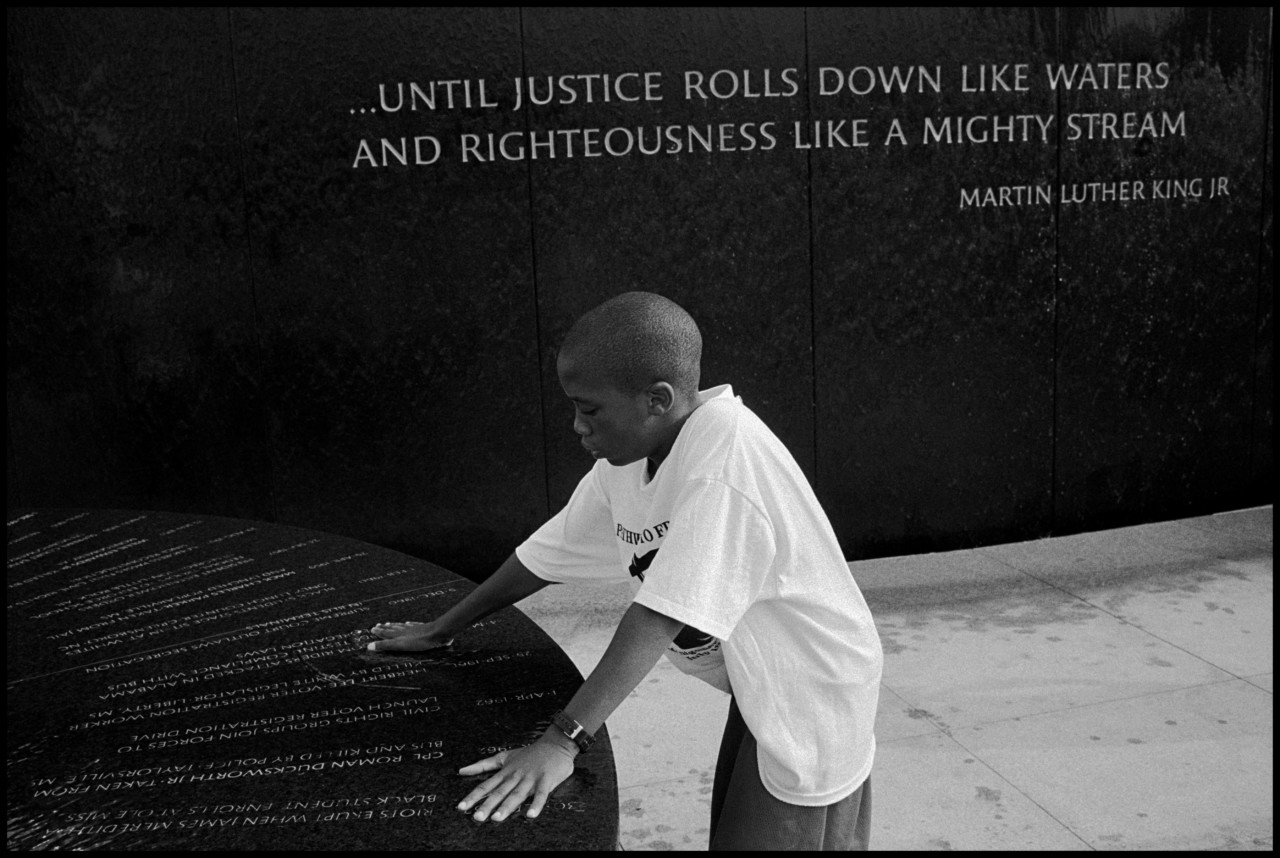

While this education fed his imagination, what was happening out on the streets—namely the Civil Rights Movement—gave him a sense of urgency that has only grown in its sense of purpose. Reed was there at the Million Man March in Washington DC in 1995, a “very emotional experience” that showed solidarity against a backdrop of disenfranchisement. He has photographed the “enduring ritual of parents and children loving each other” and watched as lovers married, families went to church and teenagers revelled in their youth.

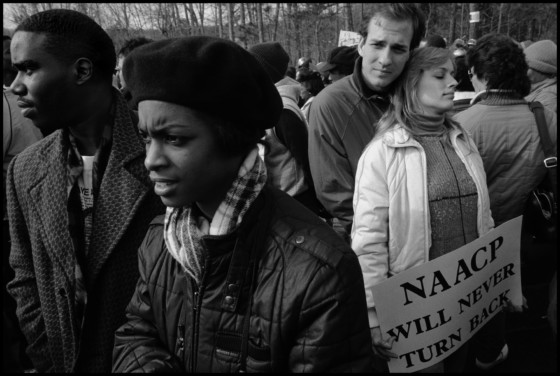

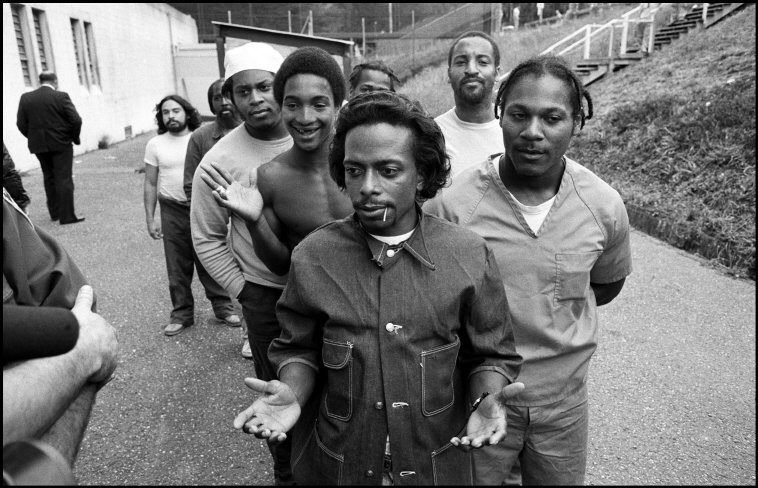

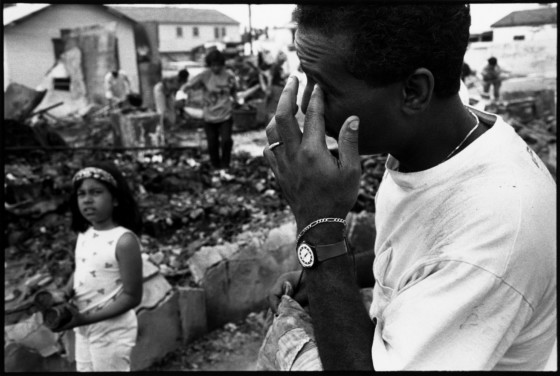

This self-assignment—still ongoing—was intended to be an “inspiring overview of one chapter in our struggle for equality in America”. But Reed’s hope has dimmed over the years as he saw fear and foreboding etched in the faces of the young, as he witnessed the struggle against the Ku Klux Klan in Forsyth County, the numerous riots between black citizens and the police and the many people of colour incarcerated in America’s prisons. “It’s an ongoing thing,” he adds. “And it’s even worse now. There is open hostility. I haven’t been going out covering specific things but I don’t have to, it’s an everyday thing. It’s what happening.”

Despite the proliferation of racial bias in America—and the apparent interest in highlighting it—Reed has struggled to get this self-assigned work into mainstream magazines. Editors often told him he was “too close to the subject”. “But they wouldn’t say that to a white photographer would they?”, he says. There was much talk, particularly on radio and television about how important it was to document the African American experience, says Reed, but “very little will to actually have someone (particularly a black someone) photograph them”.

Race relations in America today are fractious at best. A study by Public Religion Research institute in 2017 showed that 87% of black Americans say black people face a lot of discrimination today, but only 49% of white Americans said the same thing. “The problem is we have a racist in power,” says Reed. “He’s like a predatory animal. And there’s plenty of others who look at black people as if we’re so lucky to be able to walk free. It’s an endless, terrible game.”

But Reed has not given up. “I’m gonna keep on working because it’s important to me. Why else are we out here?” he asks. For Reed, photography is about being able to communicate with people, and he believes there is always the possibility of changing someone’s way of thinking. In 1976, Reed was teaching at a New York prison where the guards were reported to be openly recruiting KKK members. He remembers walking past the cells with inmates rattling their cages and threatening him. But later in the day, he struck up a conversation with a guard who was clearly a KKK member. “I think he was there because he felt he had to be,” says Reed. “But we had a long chat—he made sure it was away from the other guards—and I felt like I reached somebody then. I think I put a dent in that [mindset] hopefully.”

What has Reed learnt, having spent a lifetime witnessing self-perpetuating injustice? “Speak through your work. Say something,” he says. “Don’t just sit there and accept it.”