In Private/Mumbai

Poet, journalist, and dancer Tishani Doshi reflects upon Olivia Arthur's project which explores the boundaries and various hues of privacy, intimacy, and identity in Mumbai, India's largest city

The body in India is contested territory. Holy, defamed, groped, glorified, objectified, marginalized—rarely alone. Think of the body of ancient India and the body of contemporary India as standing on opposing banks of a river. They barely speak to one another, but they coexist. Entire museums may be filled with ancient India’s ideas of body. Body as temple, as universe, as vehicle of both the sacred and the sensual, as plural, manifold, non-binary. In the 12th century, the poet-philosopher Basavanna wrote of a kind of gender fluidity that contemporary India dreams of:

Look here, dear fellow:

I wear these clothes only for you

Sometimes I am man,

sometimes I am woman,

O lord of the meeting rivers

I’ll make wars for you

but I’ll be your devotee’s bride

(Speaking of Siva, AK Ramanujan)

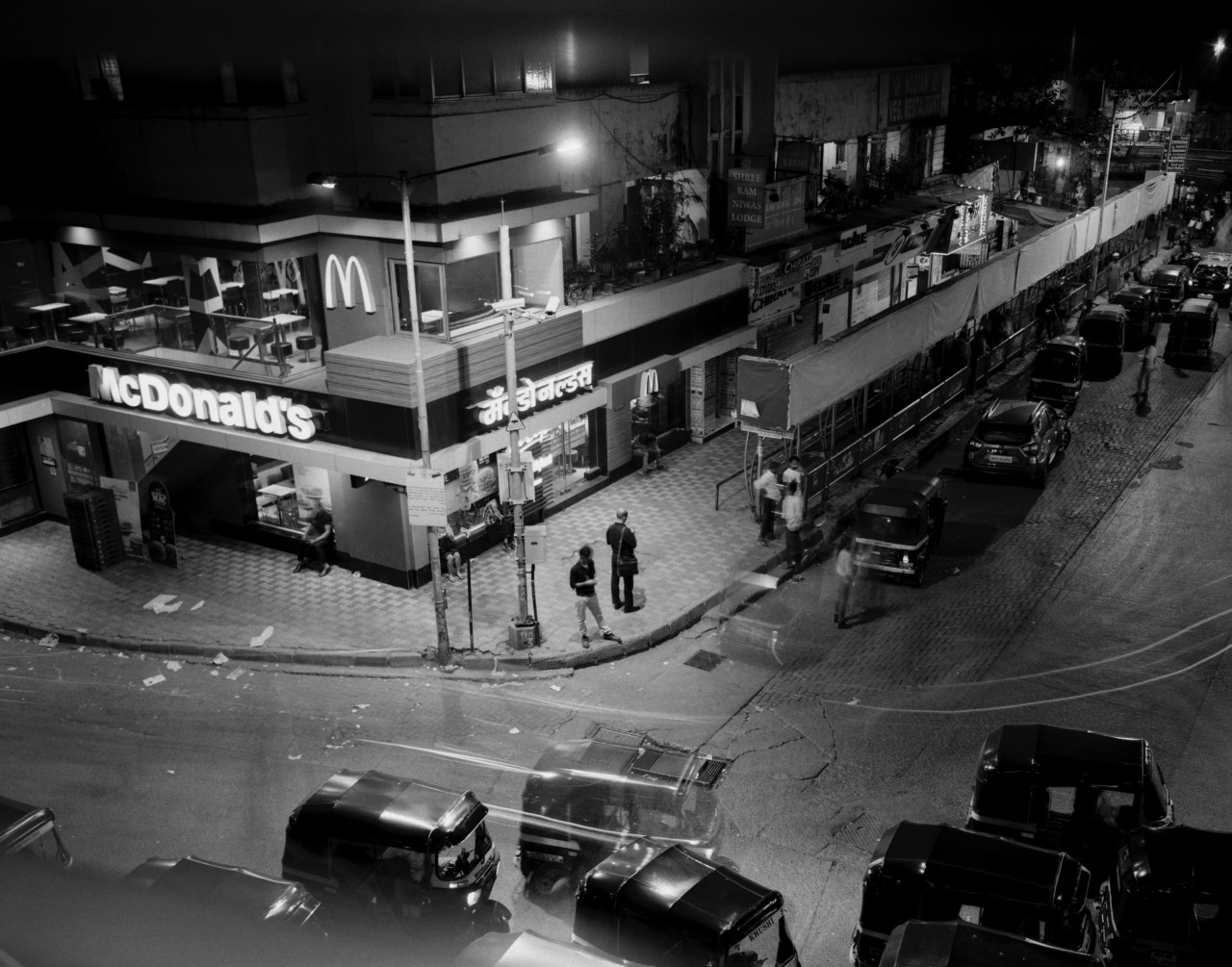

Olivia Arthur’s photographs perfectly capture contemporary India’s gender and sexual idiosyncrasies. The forced intimacy of hand over hand on a busy train, body pushing up against body in the surge of a festival crowd. The impossibility for a couple to find a secluded space in public to be purposefully intimate. In one of her photographs she offers us an androgynous back. We are invited to take in its shape — the delicate convex hillocks of shoulder blades, the faint spread of stretch marks across the waist. Gender is suspended, self is celebrated. She moves into people’s bedrooms where the body can be sequestered, stripped bare, held close against a lover. But she is also interested in the physicality that public places contain, a city’s secret thrum. In this case, the city of Mumbai, where these photographs were shot.

“Something that comes to mind a lot when I’m making this work,” Arthur says, “is the idea of shame, what you shouldn’t show, what’s not okay to show. What is shameful and why? As children you run around naked, and as you get older you can’t. I find myself asking questions from a personal point of view about the functionality of the body as opposed to how we deal with it as a society.”

While it grew to encompass all forms of intimacy and sexuality in Mumbai, the project in fact began as a collaboration with Bharat Sikka to photograph the LGBQT+ community. Until September 2018, Section 377 of India’s Penal Code criminalised homosexual activities. A Victorian legal throwback from 1861, it imposed up to ten years imprisonment for “whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal.”

In 2009, there was brief respite, with the Supreme Court revoking Section 377, calling the law unconstitutional, but pressure from religious groups saw it reinstated in 2013. The current mood in the LGBQT+ community is hopeful but wary. There is no place for full on jubilation with a fundamental right-wing Hindu government (BJP) in power that is rewriting history books and has a lackadaisical approach to protecting the rights of minority groups.

The Supreme Court passed two further landmark judgements regarding gender, sexuality and privacy. It struck down Section 497, decriminalising adultery, making it so adultery would still be a civil offence and grounds for divorce, but removing the state’s right to interfere in personal autonomy. It also passed a verdict allowing women to enter the Lord Ayappa Temple at Sabarimala in Kerala, which for centuries had prevented women of menstruating age from entering the shrine for fear of enticing the residing bachelor deity. When women actually tried to enter the temple though, there were riots, proving that judiciary and societal ideas are rarely in alignment.

To view Arthur’s photographs in this context is to understand the kind of seismic changes that India is undergoing in trying to reconcile those two bodies standing across from each other on the river’s respective banks — the ancient and the contemporary. There is a frankness about her portraits. A quietness. A person in a padded bra stares unabashedly into the frame. An elderly figure in a chair turns his head away from the light in somewhat melancholic fashion, toes of one foot en pointe like a ballet dancer. “I had no idea whether people would be willing to make these pictures when I came to Mumbai,” Arthur says. “It was interesting to see how people could be relaxed, how much bolder people were than we thought they’d be. There was a real readiness to be out there.”

Arthur photographed this series on Linhof and Graflex large format cameras. She describes them as old fashioned cameras where the photographer has to put her head under a cloth. “There’s nothing discreet about it,” she says, “And anyway, I stick out in India as a foreigner. I don’t just melt into the crowd. This is a great, big, in-your-face camera, which is one of the things I like about this approach. There’s no pretence. I’m obviously taking these pictures, but at the same time getting crushed around, trying to handle the camera. I like the experience. The quietness the camera gives me when I photograph people at home, and the sort of madness it gives me in the other space. It’s a slower way of taking pictures.”

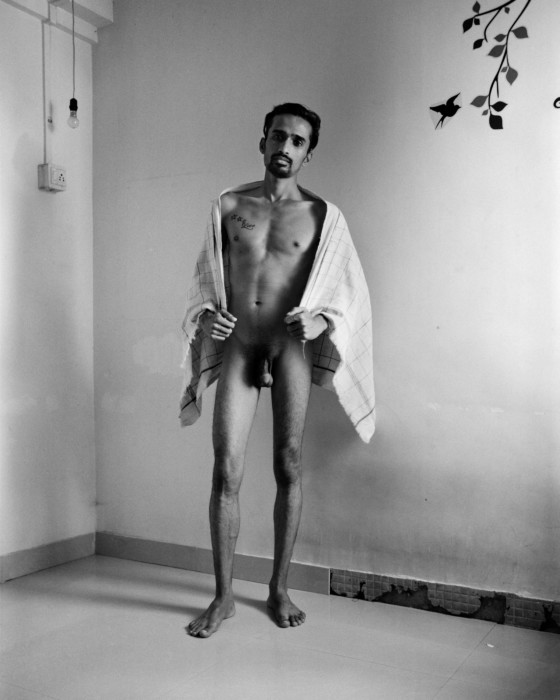

Two photographs from the series weren’t allowed to be shown in her exhibition in Mumbai. The first is a frame of two women naked and kissing, reminiscent of a Japanese Shunga, tentacular and unrestrained. The other — a candid frontal of a young man holding a towel as if it were a superhero’s cape across his shoulders. “It was a shame,” Arthur says, “Because these people had been really strong. They knew their picture was going to be shown in the city and they were kind of proud. But we were able to later show it in London.”

"To view Arthur’s photographs in this context is to understand the kind of seismic changes that India is undergoing in trying to reconcile those two bodies standing across from each other on the river’s respective banks — the ancient and the contemporary"

- Tishani Doshi

The insidious problem of censorship runs deep in India. Nude photographs may not be allowed in an art exhibition, but nobody flutters an eyelash about the nation being the third highest consumer of porn in the world after the US and the UK. For all the changes in judiciary, draconian laws still exist. Marital rape is not a criminal offence, a new Transgender Persons Protections Bill is being rejected by the trans community who say it criminalises them, and the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act remains a serious threat to activism and free speech. The writer Arundhati Roy wrote of India’s problem with censorship, “Fortunately we are an irredeemably untidy people. And hopefully we will stand up to them (the BJP government) in our diverse and untidy ways.”

"The luxury of space in India diminishes each year. The idea of a room of one’s own is quite foreign. People must find private spaces even when they are with other people"

- Tishani Doshi

This untidiness is what Arthur’s series encapsulates. The contradictions and brutalities that patriarchy continually throws up, the messiness of humans that prohibits them from sticking within prescribed dichotomies. The series also hints at how we may find resolution. In private moments of calm, truth and disclosure. The luxury of space in India diminishes each year. The idea of a room of one’s own is quite foreign. People must find private spaces even when they are with other people.

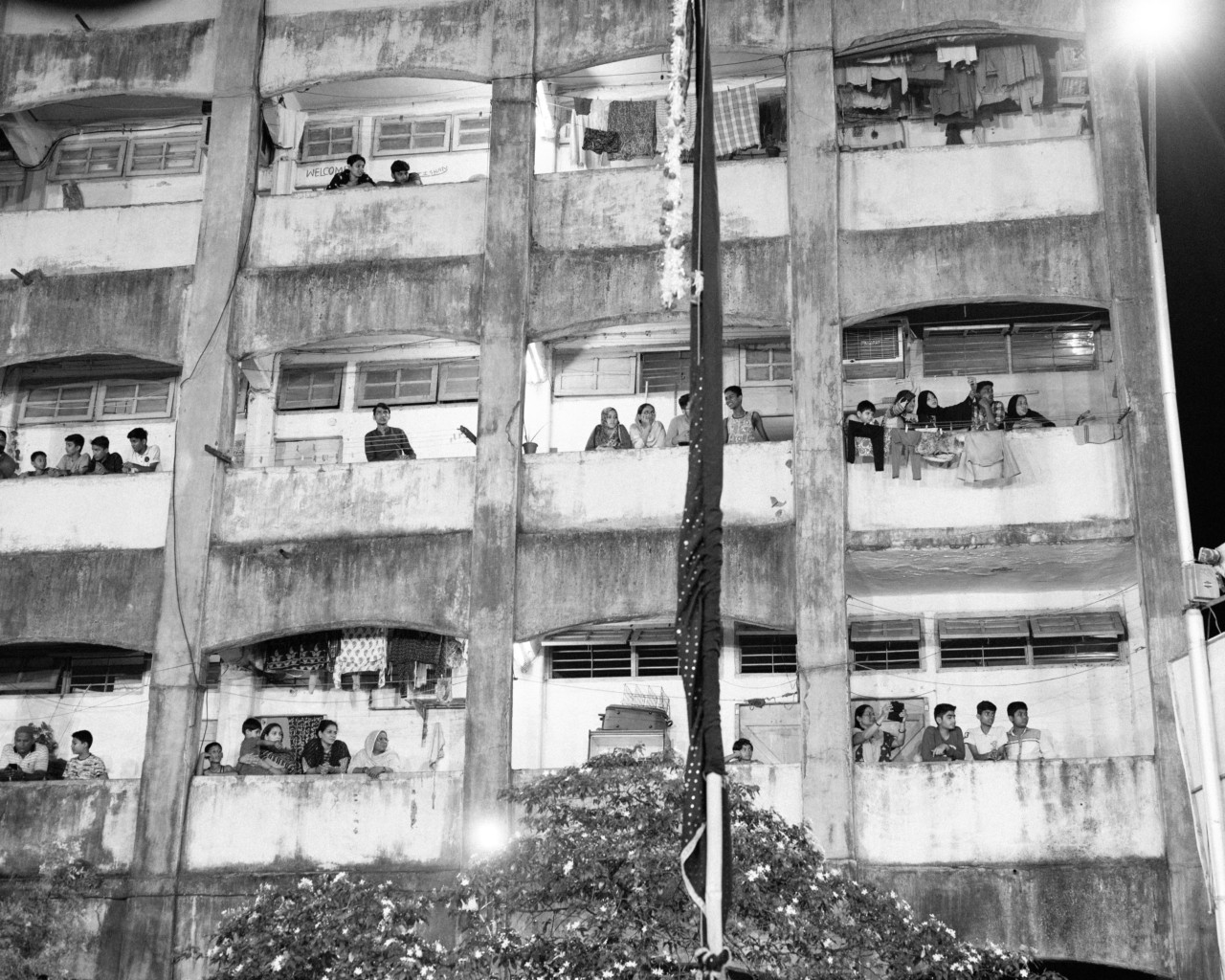

We see this beautifully depicted in one of Arthur’s photographs of a nondescript apartment building where people stand out on their balconies. She tells me they are watching the Ashura procession, which marks the tenth day of Muharram. It is a festival observed by Shia Muslims – one of mourning and self-flagellation. In the photograph, we see none of this. One woman in a burkha is taking a selfie, another is photographing the procession, a man looks into his phone. The range of emotions they display represent an entire spectrum — bored, concerned, joyful. Some stand alone, some gather in groups. All have the body language of the voyeur, which is the perhaps the most apposite position in India.

"Some stand alone, some gather in groups. All have the body language of the voyeur, which is the perhaps the most apposite position in India"

- Tishani Doshi

The people in Arthur’s photographs look back at us. They hint at ways in which the body can arc back to a more seamless state of being — able to morph into cloud, animal, god, container of both kama and bhakti/eros and agape, Shiva and Shakti/ male and female — a more complete, less shackled version of ourselves.