On This Day in History: The Little Rock Nine Start School

A photographer's perspective on a defining moment in America's Civil Rights movement, when nine children were finally able to begin the school year, on September 25, 1957

On September 25, 1957, a landmark moment in America’s Civil Rights movement took place in Little Rock, Arkansas, when the so-called Little Rock Nine entered their newly-desegregated high school for the first time. Magnum photographer Burt Glinn documented the history-defining episode; here, we review his notes from the time of the shoot as well as provide the context to these well-known images of a pivotal time in American history.

Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas was set to begin the 1957 school year desegregated. The 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Topeka had made segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Previously, a 1955 ruling (Brown II) ordered that public schools be desegregated with “all deliberate speed,” urging on the move towards desegregation without delays.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) attempted to register black students in previously all-white schools in cities throughout the South. In Little Rock, Arkansas, the Little Rock School Board agreed to comply with the ruling. A plan to begin the gradual integration was to be implemented in the fall of the 1957 school year, with nine students registered, due to start classes in September 1957. However, the Governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, defied both of these rulings.

On September 4, 1957, the first day of classes at Central High, Faubus called in the state National Guard to bar the black students’ entry into the school.

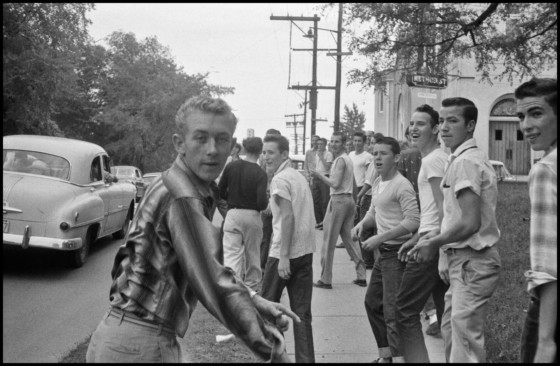

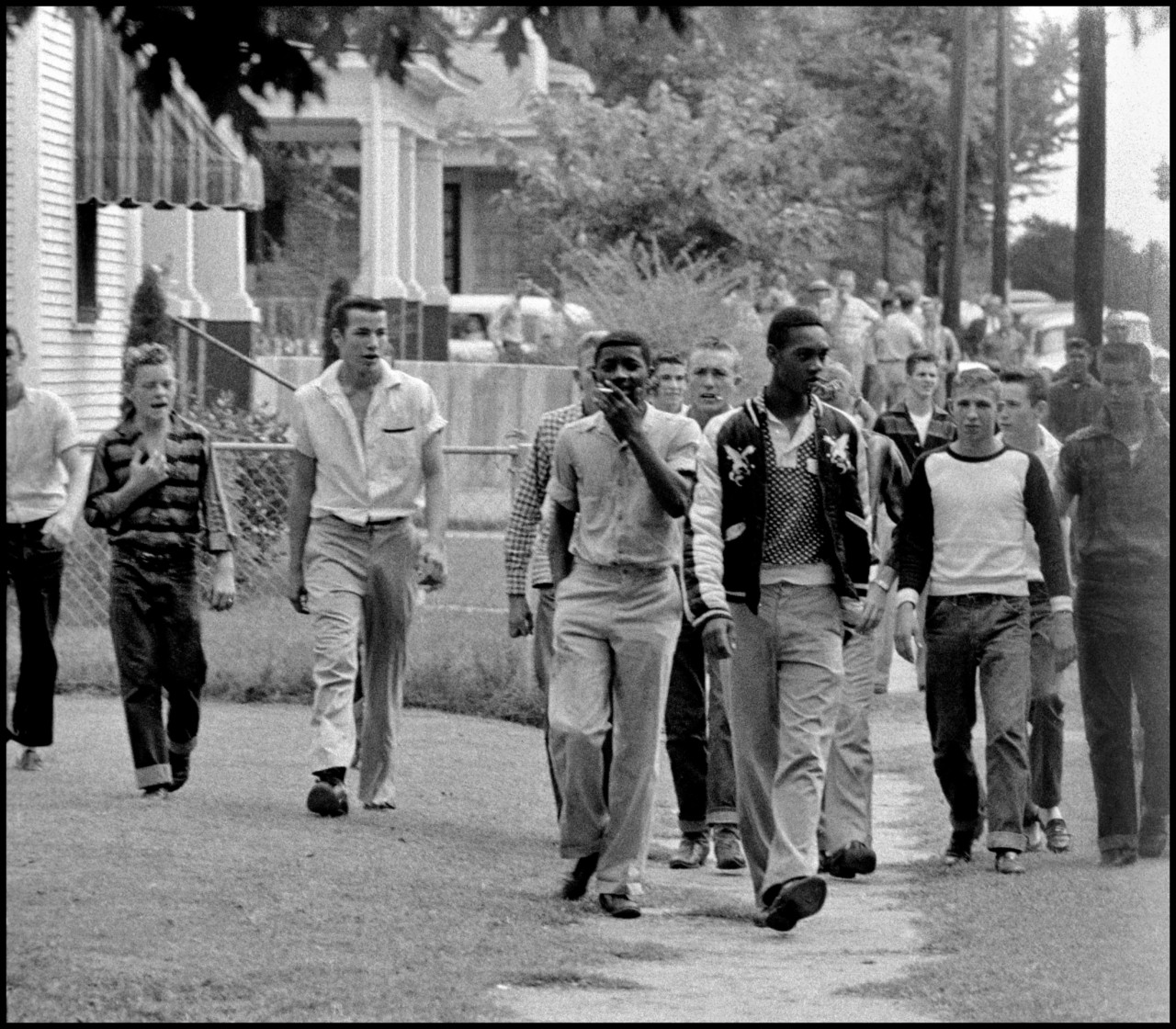

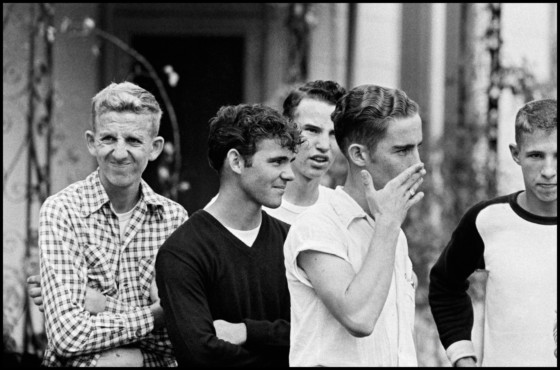

As the nine African-American students approached the school, they were met by a hostile crowd consisting of students, parents and local people, who prevented them from remaining at school. Remembering that day, one of the nine students, Elizabeth Eckford, recalled:

“They moved closer and closer. … Somebody started yelling. … I tried to see a friendly face somewhere in the crowd—someone who maybe could help. I looked into the face of an old woman and it seemed a kind face, but when I looked at her again, she spat on me.”

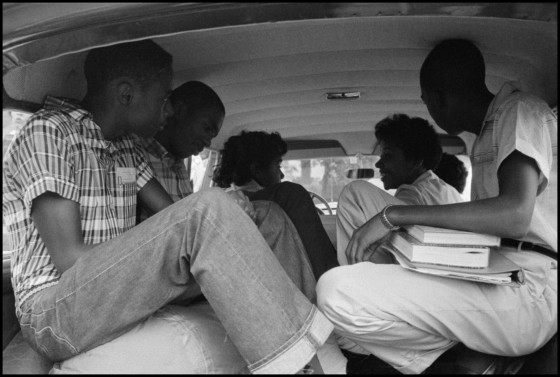

Later in the month, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent in federal troops to escort the “Little Rock Nine” into the school, and they began their first full day of classes on September 25. According to the late John Morris, former Executive Editor at Magnum Photos, Burt Glinn volunteered to shoot the story for Life magazine. In the book Get The Picture, Morris said that this came during a time when many Life photographers were getting beaten up whilst on assignment.

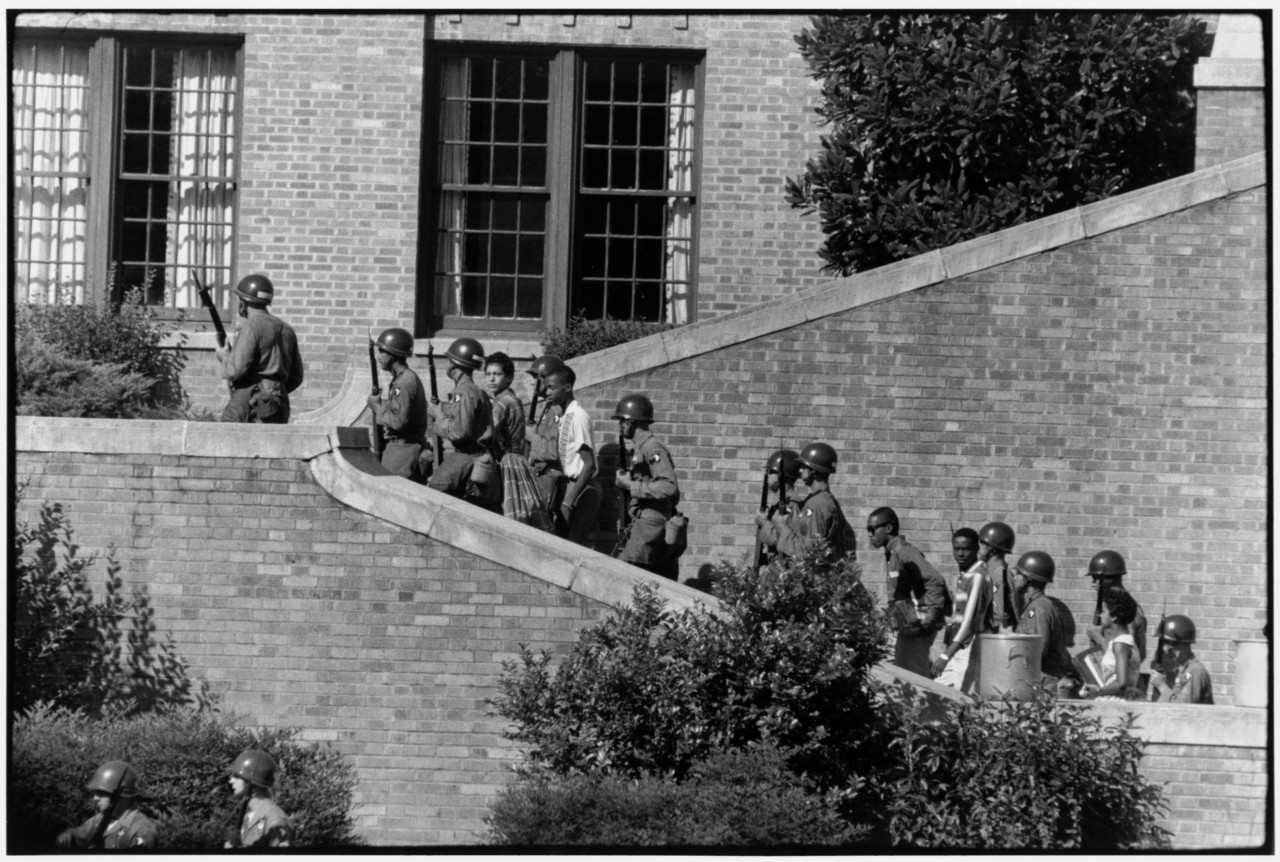

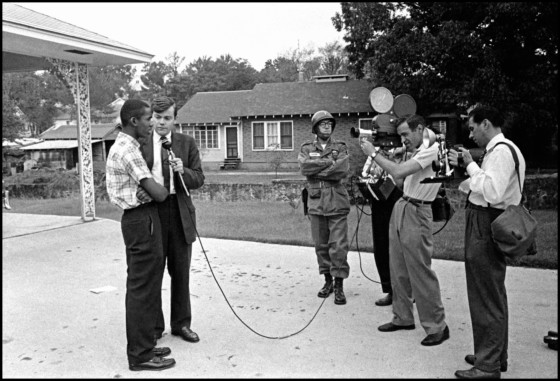

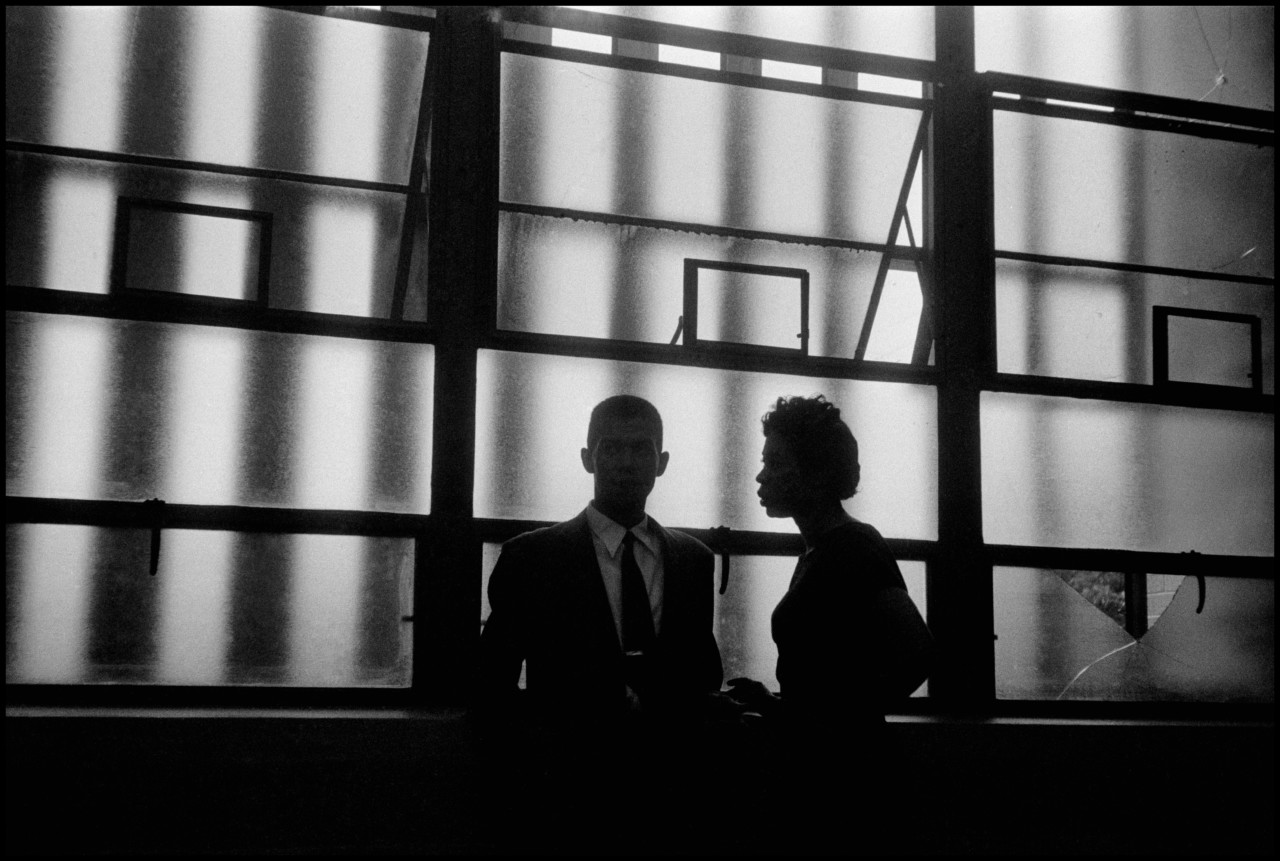

Burt Glinn’s images capture armed paratroopers escorting the black children into school, and also picture the scenes around the school, where huge tanks have pulled up beside quiet suburban lawns. The journey into school for the black children is traced through onlookers, jeering crowds and reporters.

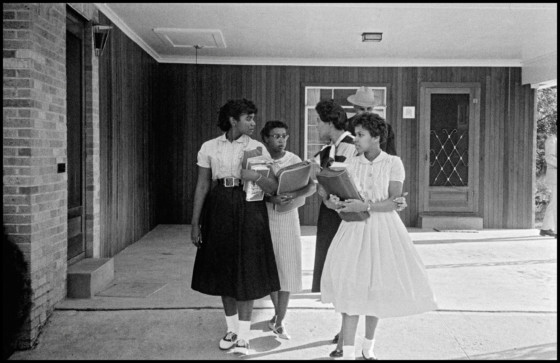

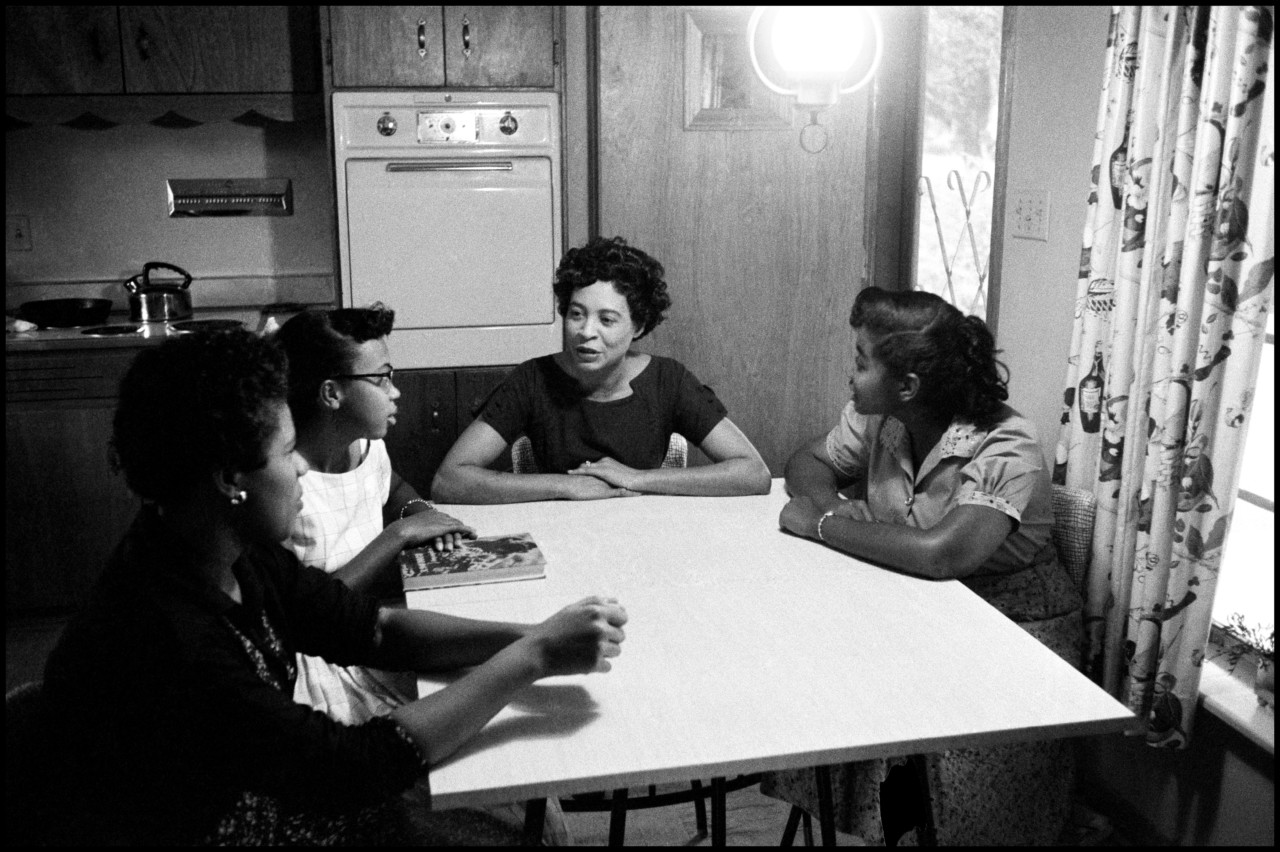

Glinn also followed the story to a television news studio where Governor Orval Faubus gave a public address, and to the home of Daisy Bates, President of the NAACP’s Arkansas branch, who congratulates three of the girls after completing their first day of school.

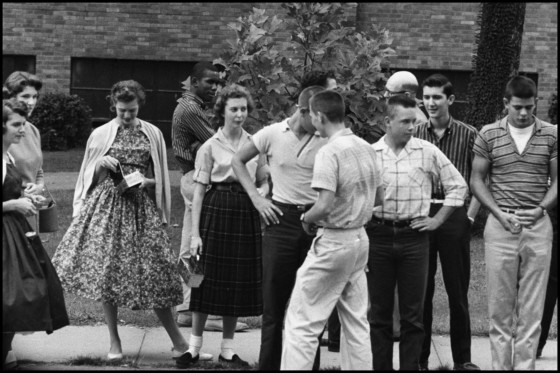

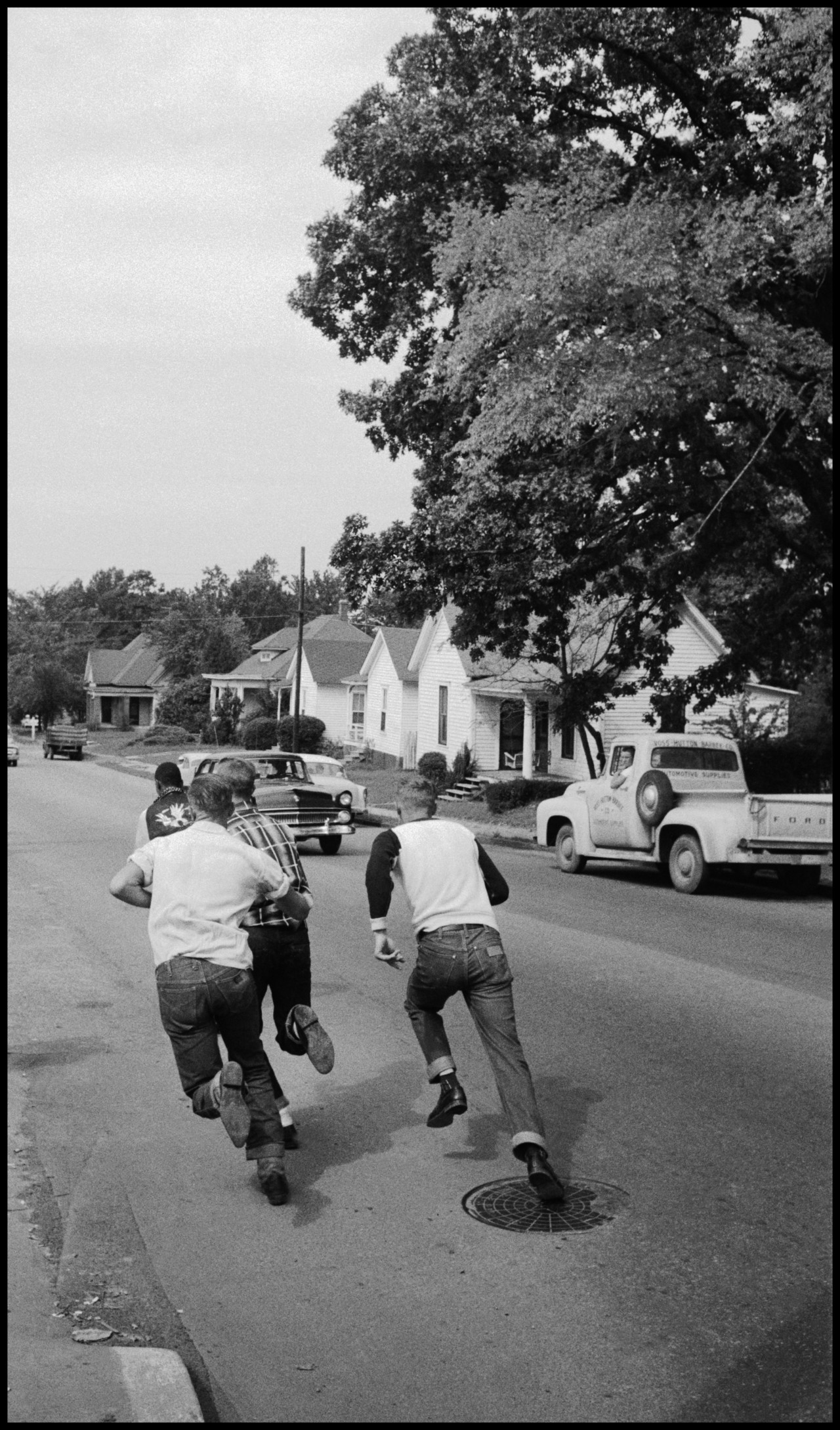

In his original typed notes for the story, Glinn described witnessing a scuffle between a group of white boys who chased black student Lawrence Coley. He also provided context to a shot where children are seen to be happily clapping whilst the young black male student seems disengaged. He wrote that “to pass the time (30 minutes) during a fire drill, students practice school songs and cheers used at football games…Terrence Roberts stands off to one side, in a world of his own.”

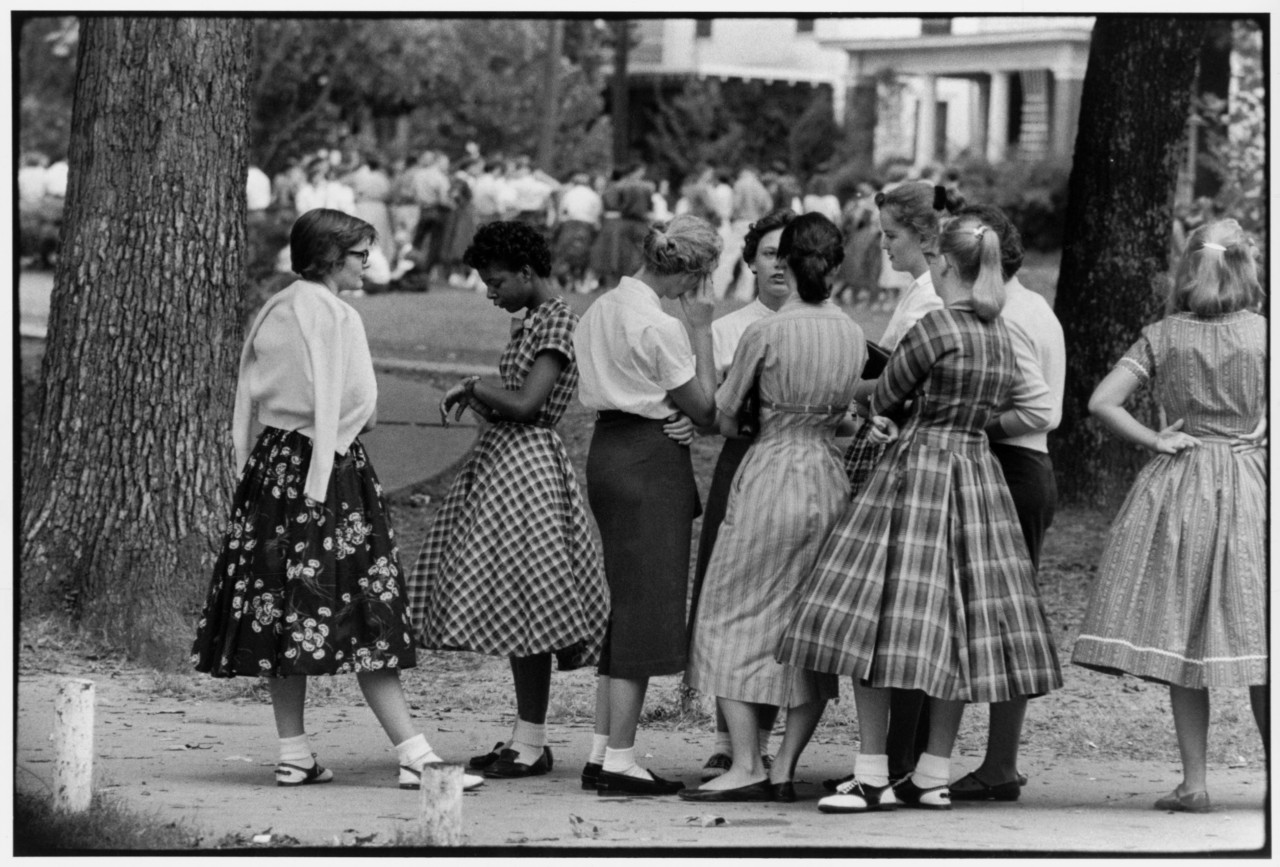

At around 10am on September 25th a bomb threat caused an evacuation. Glinn captured the students waiting outside, picturing black student Minnijean Brown talking to a group of white girls during the drill. “Minnijean Brown continues to talk to other girls during a fire drill,” say Glinn’s notes “but soldiers of the 101st airborne division in the background serve as reminder of surrounding tension.”

Craig Rains, a white student at Central High, who argued that he was opposed to integration on the grounds relating to state-law issues, remembered the National Guard’s arrival in an interview archived by Washington University:

“I had gone down to the school, the night before it opened, and just kind of a tradition, I was going to meet some friends down there, and I was sitting there, outside the school, waiting for them, and I heard some pretty loud noises coming down the street. And I looked up and saw a convoy coming down. And I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. It was military vehicles, and they started rolling by me, and started parking in all of the intersections, all around the school… I didn’t know whether they were the good guys or the bad guys. I didn’t know whether they were National Guard or federal troops, what they were. And didn’t know until I got home, and it was all on television about the fact that Governor Faubus had called out the National Guard.”

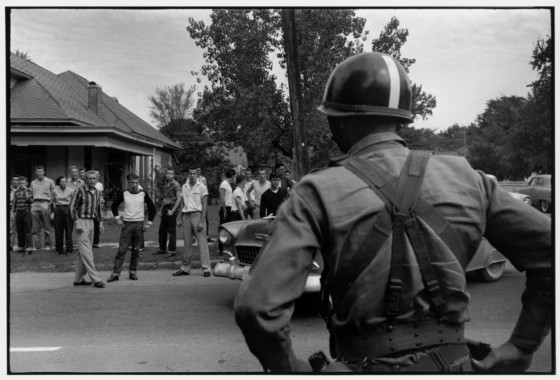

Glinn’s notes portray the seriousness with which the troops took to their role to enforce integration: “soldiers of the 101st Air-borne division order a gang of 3 high school boys who opposed integration and had gathered near the school in protest to ‘move on’. Soldiers showed with pointed bayonets that they meant business,” he wrote.

See more of Magnum Photographers’ coverage of the civil rights movement in America here.