They Defend our Freedoms

Acclaimed French journalist Éric Fottorino delves into the history of human rights for Magnum and the European Parliament

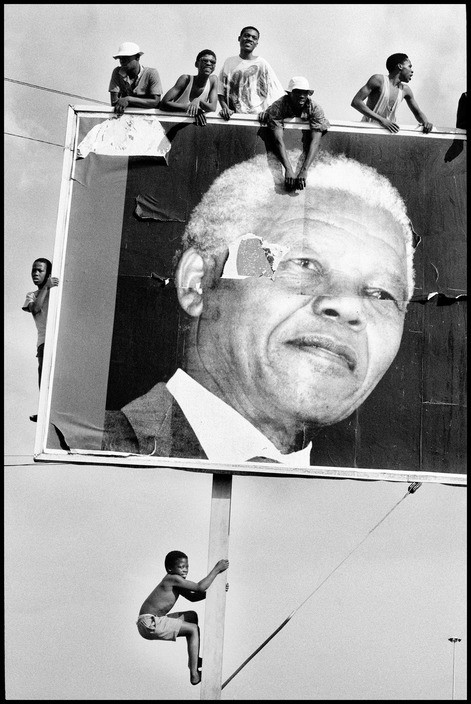

Awarded for the first time in 1988 to Nelson Mandela and Anatoli Marchenko, the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought is the highest tribute paid to human rights work by the European Union. It gives recognition to individuals, groups and organizations that have made an outstanding contribution to protecting freedom of thought.

To mark 30 years of the Sakharov Prize, Magnum photographers Jérôme Sessini, Bieke Depoorter, Enri Canaj, and Newsha Tavakolian have worked with four remarkable individuals, all staunch defenders of human rights, to shine a light on their work. A commission for European Parliament, these stories are gathered in a new book and exhibition which will launch this month, and the work will be serialized on Magnum Photos over the coming weeks.

“This book is about all those who — just as the laureates — fight for their rights and fairer societies while motivating others to do the same,” wrote Antonio Tajani, President of the European Parliament in the book’s introduction.

Magnum will be serializing the work over the coming weeks. In our first chapter, an extract from the essay They Defend Our Freedoms, by acclaimed French journalist Éric Fottorino, we explore the history of human rights and those who have fought for them, illustrated here with the extensive historic work of Magnum photographers, for documenting – and defending – those human rights abuses and issues is central to the agency’s work.

"Human rights. Two short words with a long history"

- Éric Fottorino

They Defend Our Freedoms (extract)

Human rights. Two short words with a long history. Two short words which, armed only with the force of an ideal, do so much to prevent human beings from preying on one another. How many ideals and struggles are encapsulated in this term? How many tortured faces have been banished from the world of the living? How many charters and resolutions, protocols and pacts, conventions and petitions are there? How many hopes and battles against the arbitrary? How many places on this planet where the force of law has finally won out over laws imposed by force?

These are always uncertain victories, which, lest we forget, are constantly undermined by complacent, empty rhetoric of the ‘never again’ variety. The formal agreements binding all nations did not do anything to prevent a series of genocides throughout the 20th century, even though the preamble to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights is very clear as to what our aim should be:

‘Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people’.

This prefigured Article 1 of the declaration itself, which bears the stamp of Eleanor Roosevelt and the French lawyer René Cassin: ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.’ The Shoah was followed by the slaughter perpetrated by Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, the Rwandan genocide and the mass killings of Bosnians carried out by Serb soldiers at Srebrenica. Other massacres in Latin America, in Darfur, in Congo, in Iraq, in Yemen and in Syria — the list goes on — have provided further proof of the willingness of regimes and countries to trample under foot fundamental human rights, which the inter- national community continues, in the face of all the evidence, to proclaim as universal, inalienable and indivisible.

A list of the most serious instances of human cruelty towards others would highlight at least three types of large-scale repression which have gone on simultaneously since the end of the Second World War: state communism, totalitarian and imperialist, as exemplified by the Soviet gulag and its inmates, known as zeks; Moscow’s snuffing out of the revolts in the satellite countries of the former USSR — Budapest in 1956 and Prague in 1968 —; China’s Cultural Revolution, which claimed the lives of 1 million people between 1966 and 1968; or the crushing of the student uprisings at Tiananmen Square and the massacres of peaceful Tibetans.

Then there are the colonial wars, which, from Vietnam to Africa, decimated civilian populations, turned children into cannon fodder and women into sexual objects and forced millions of ordinary people into exile. I am thinking of the Vietnam War, of course, and of the war in Algeria, which at the time were merely seen as local conflicts.

"Reading the list of winners is enough to be reminded that the work of defending human rights takes many forms: upholding democracy, safeguarding freedom of thought, "

- Éric Fottorino

Lastly, there are the Latin American dictatorships, Vargas’s Brazil, Pinochet’s Chile and General Videla’s military junta in Argentina. In the 1970s, these regimes provided the most glaring examples of human rights violations. Who could have forgotten the young opponents of the regime who were thrown into the sea from helicopters, or the determined struggle by the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo — dubbed the ‘madwomen of the Plaza de Mayo’ by the military — to find their children who had been kidnapped during Argentina’s long night of terror? In 1992, these courageous women were awarded the Sakharov Prize, which this year is celebrating the 30th anniversary of its inception.

Reading the list of winners is enough to be reminded that the work of defending human rights takes many forms: upholding democracy, safeguarding freedom of thought, combating torture and all forms of discrimination, condemning arbitrary decisions to deny people freedoms on religious, racial or political grounds or for reasons linked to their sexual orientation.

"Throwing the spotlight on them is often also a way of protecting them from their enemies and offering them conspicuous backing. "

- Éric Fottorino

Awarded for the first time in 1988 to Nelson Mandela and Anatoly Marchenko (posthumously), this prestigious distinction does not only reflect the European Parliament’s determination to defend fundamental rights. It is also intended as a mark of support for the men and women who take great risks to advance the cause of freedom in their respective countries. Throwing the spotlight on them is often also a way of protecting them from their enemies and offering them conspicuous backing. Because in almost all parts of the world, defending freedoms and democracy is a dangerous activity which costs many activists their lives.

Winners of the Sakharov Prize include heroes who were previously anonymous and have now become the public face of a struggle: Denis Mukwege, who saved the lives of so many women in the Democratic Republic of Congo, had been appallingly mutilated; the young Pakistani woman Malala Yousafzaï; or the two young Yazidi women from Iraq, Nadia Murad and Lamiya Aji Bachar, who narrowly escaped the worst of the horrors perpetrated by Da’esh before leading the fight against the trafficking of women. Mothers, artists, anti-torture and pro-peace activists, representatives of ethnic minorities and the United Nations as an institution: from the start the Sakharov Prize has made bold and eclectic choices when choosing recipients who embody the struggle of the human face against the inhuman.

See the stories from this series here.