Narratives of the Unseen

Prisons and the Incarcerated: looking at the role of photography in exploring detention through the Magnum archive

‘The problem is not that people remember through photographs, but that they remember only the photographs… Narratives make us understand. Photographs do something else: they haunt us.’

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others.

The word prison carries many connotations; of confinement, discipline, criminality, but also invisibility. In the United Kingdom, the rise of the panopticon-style prison took place in the late 18th century, based on the designs of Jeremy Bentham. This was a type of architecture developed around a mode of surveillance; the theory being that discipline could be enforced upon inmates through a centralized watchtower with a 360° view of the facility and its occupants. In spite of this long-standing obsession with authoritarian omnipotence within them, prisons are out of sight, and indeed out of mind. They are however a lived and visceral reality for many. It’s these unseen, and unknown spaces of unrest where photography records and archives life, time and the body.

The writer and theorist John Tagg described the relationship between photography and its role in creating representation politically. He writes, ‘like the state, the camera is never neutral. The representations it produce[s] are highly coded, and the power it wields is never its own’.

In this vein, how does photography intervene within that invisible world of prisons, permitting a reality of its own? What narrative and reimaginings of the inside can photography create, and how can it challenge perceptions of incarceration?

Photographs have the capacity to provide a degree of transparency, allowing the public to witness the ideologies of prisons playing out in a broader social context. But the difficulty in accessing these spaces physically prompts questions of the ethics of photographing detention. If photography can capture worlds which are often invisible to broader society, what responsibility do we bear as consumers of these images? We all consume images of prison, while aspects of prison are simultaneously hidden from our view— we consume representations which are detached from the fraught reality of this system. By capturing the reality of these spaces – both physical and emotional – photographers generate an archive of unseen experience, community, and at times dehumanisation.

In his image of Gidani Prison, Mark Power photographs the fraught relationship between the inside and outside of a facility situated in a melancholy, barren landscape. The distant mountains descend from the right-hand corner of the image, acting as an empowering backdrop to a desolate prison. Three minute figures scattered across the scene act as reference points; one person gazes from the prison watchtower, and two others walk on land adjacent to the building. The majority of the image is of the vast landscape and the prison’s remote surroundings. The picture reminds the viewer that prisons function to sanction and hide the incarcerated – who are strikingly invisible in this image; their walls as well as their ideologies operate as a tool to render inmates invisible.

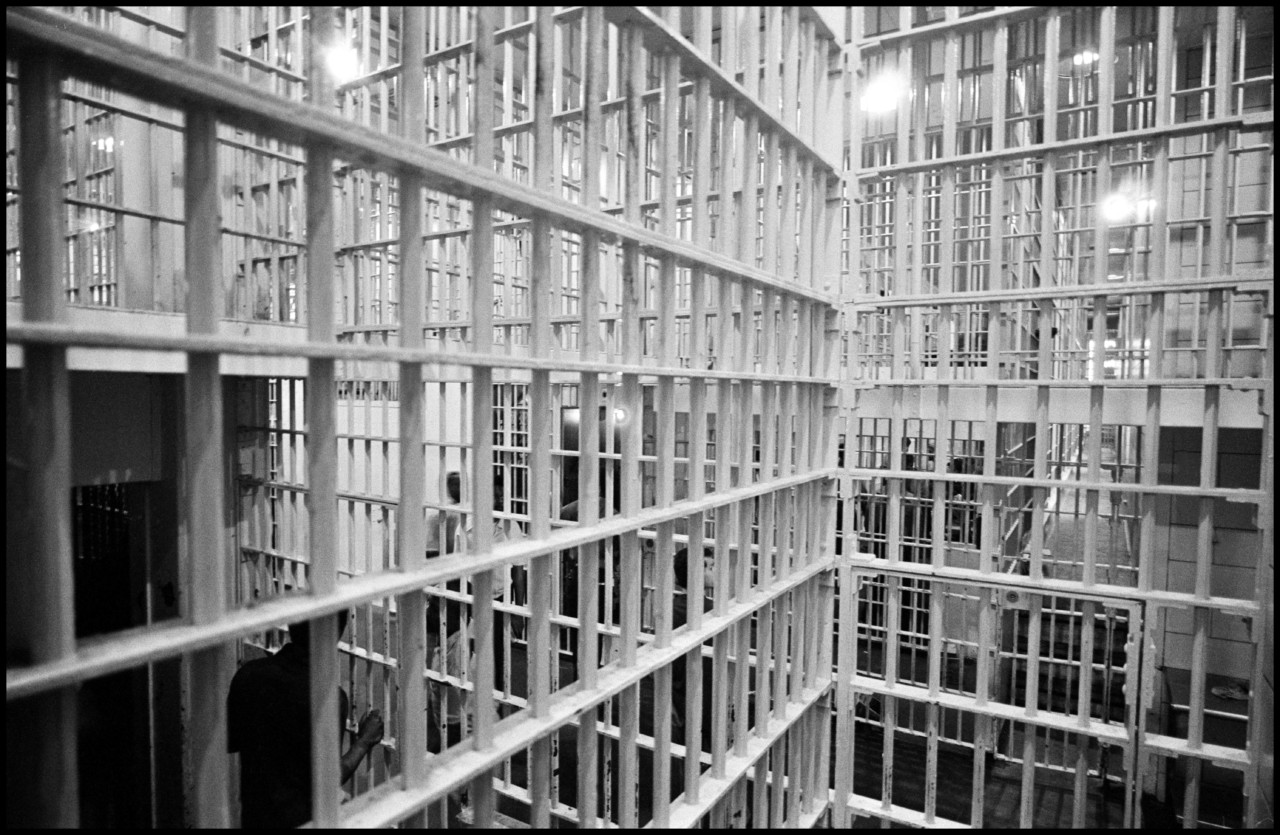

This territory is often unseen by broader society, but photography’s intervention can undo that, and expose this hidden world. Jim Goldberg’s photographs of the prison industrial complex (a term coined to describe the large-scale and increased integration of policing and imprisonment with the interests of private bodies in the USA from the 1970s onwards) intersect the lived reality of incarceration through a poetic methodology. In his 2002 series, made in Illinois’ Stateville Prison, the disciplinary, abject space of prison comes across as a hostile, clinical environment. That same panopticon concept that flourished in 18th Century Britain was echoed in Stateville, its construction completed 1919, and is on show in Goldberg’s images. The photographer captures a section of the prison where inmates wait to be transferred to other long-term cells, everything on view under the panopticon mode of surveillance. Time seems to stand still yet the emotions, lives, and realities which inhabit the prison continue. Glimpses of the (not-so) private spaces of these individuals contrast with the all-seeing eye of the institution.

Time has a direct bearing on how the body is governed within prisons. How does it feel to have your agency controlled by an institution? The physical expropriation of one’s body is a disciplinary method central to the surveillance which the carceral system imposes on its detainees. Indeed, by being physically contained the inmates are forced to endure isolation, and longing for a different physical and psychological reality.

When a person’s daily routine becomes predictable, time becomes elongated, suspended and acutely apparent. How do prisons, and the entities which run them, use time as an emotional weapon?

Time in the criminal justice system begins well before incarceration; from the moment of arrest the accused citizen anticipates the trial and possible sentence, all of which impose an inevitable lack of control over a person’s life. Which is to say, the reality of incarceration isn’t just physical: it exerts itself prior to imprisonment, and lingers beyond prison walls. However, once the inmate is inside, awaiting trial, or in some cases on parole – time morphs into a different reality; days become sanctioned in a foreign mode, time is regulated and imposed upon the prisoners. How can this elongation of experience be portrayed in the photographic image?

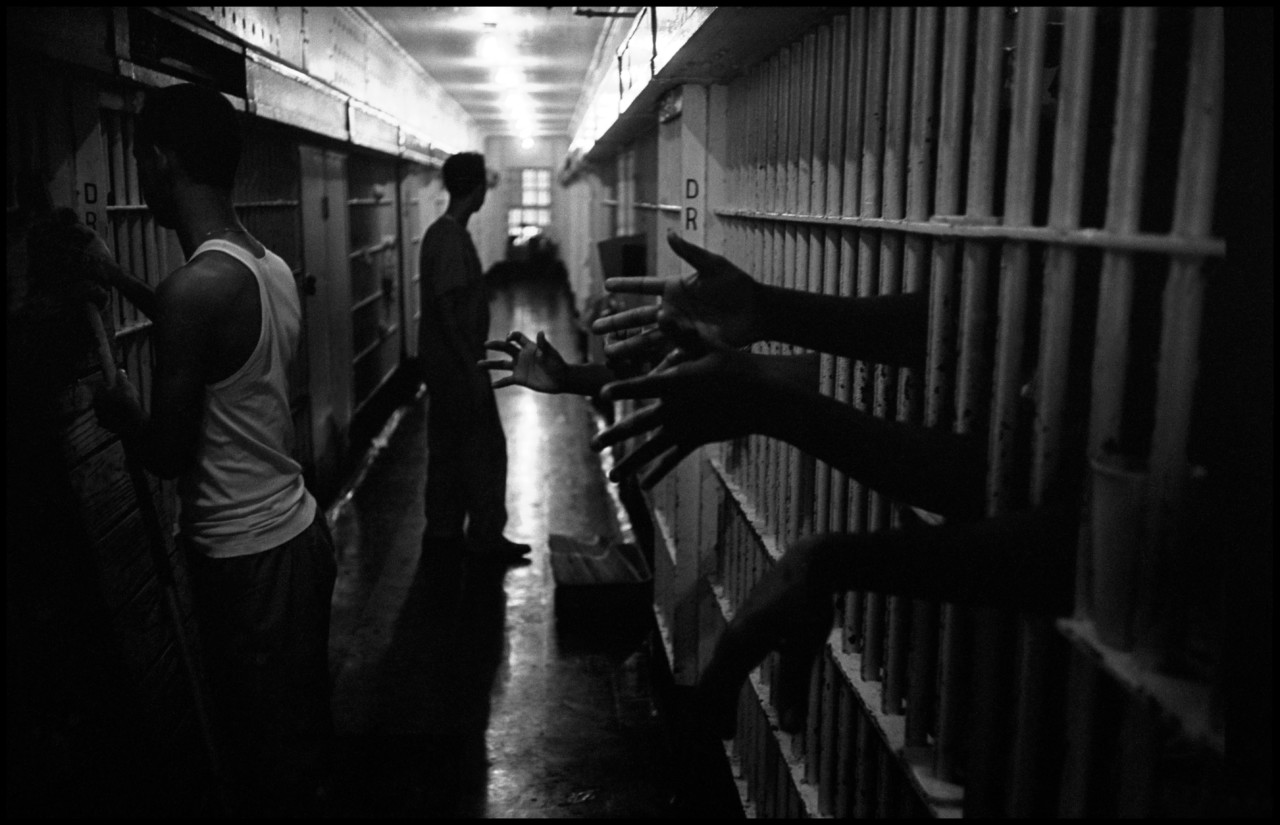

In Aperture’s Prison Nation issue, photographer Pete Brook asks the question: ‘What images shape our imagination of and future responses to mass incarceration?’ He raises an important tension; inasmuch as the photographic image is captured fleetingly, how does it bear witness to the alternative experience of time in prison? Leonard Freed’s 1963 photograph from a city prison in New Orleans, Louisiana, demonstrates the lack of agency these systems impose on their subjects. Hands expressively emerge from their cells… The gesture suggesting a sense of longing for connection, for togetherness. In the background a figure approaches the cell from a distance. The hands in the forefront of the image are emotionally charged in anticipation of this meeting. Time here seems to be informed by two factors; the lived, visceral experience of captivity, and the suspension of agency.

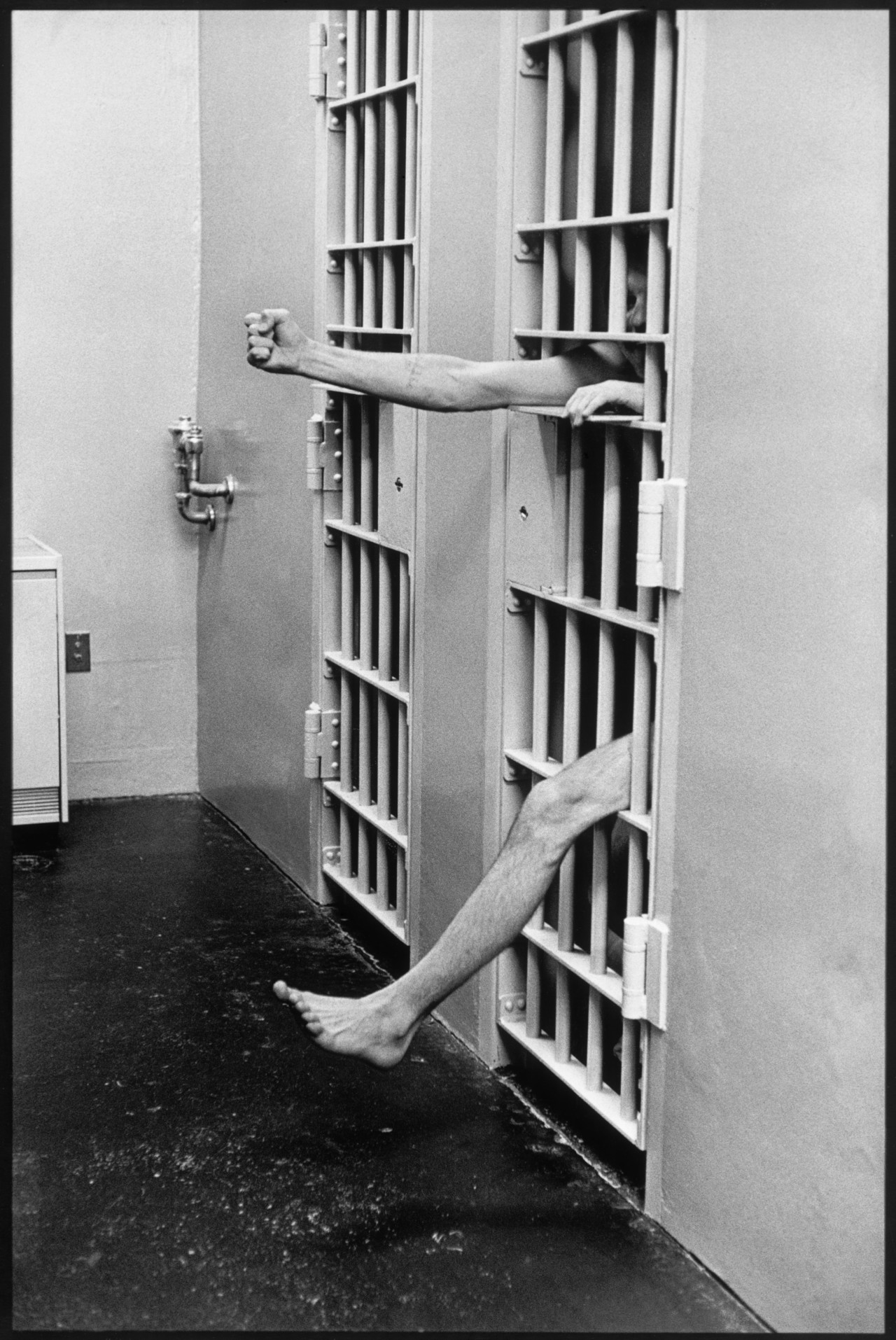

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s 1975 photograph, made in the solitary confinement cells of New Jersey’s Leesburg Prison, meditates on the discipline of the body and its ability to intervene physically when imprisoned: a leg assertively moves between the cell’s bars, as a seeming announcement of the prisoner’s physical existence. The gesture of the body here is twofold; on the one hand, it demonstrates the desire to exist beyond confinement, while also acting as a pronunciation of the body when the face is invisible: a fist forcefully penetrates the air, protesting against entrapment. It is this duality which is perhaps most striking to the viewer, the photograph manages to juxtapose a sense of claustrophobic entrapment with the body’s vigorous action in defiance of this setting.

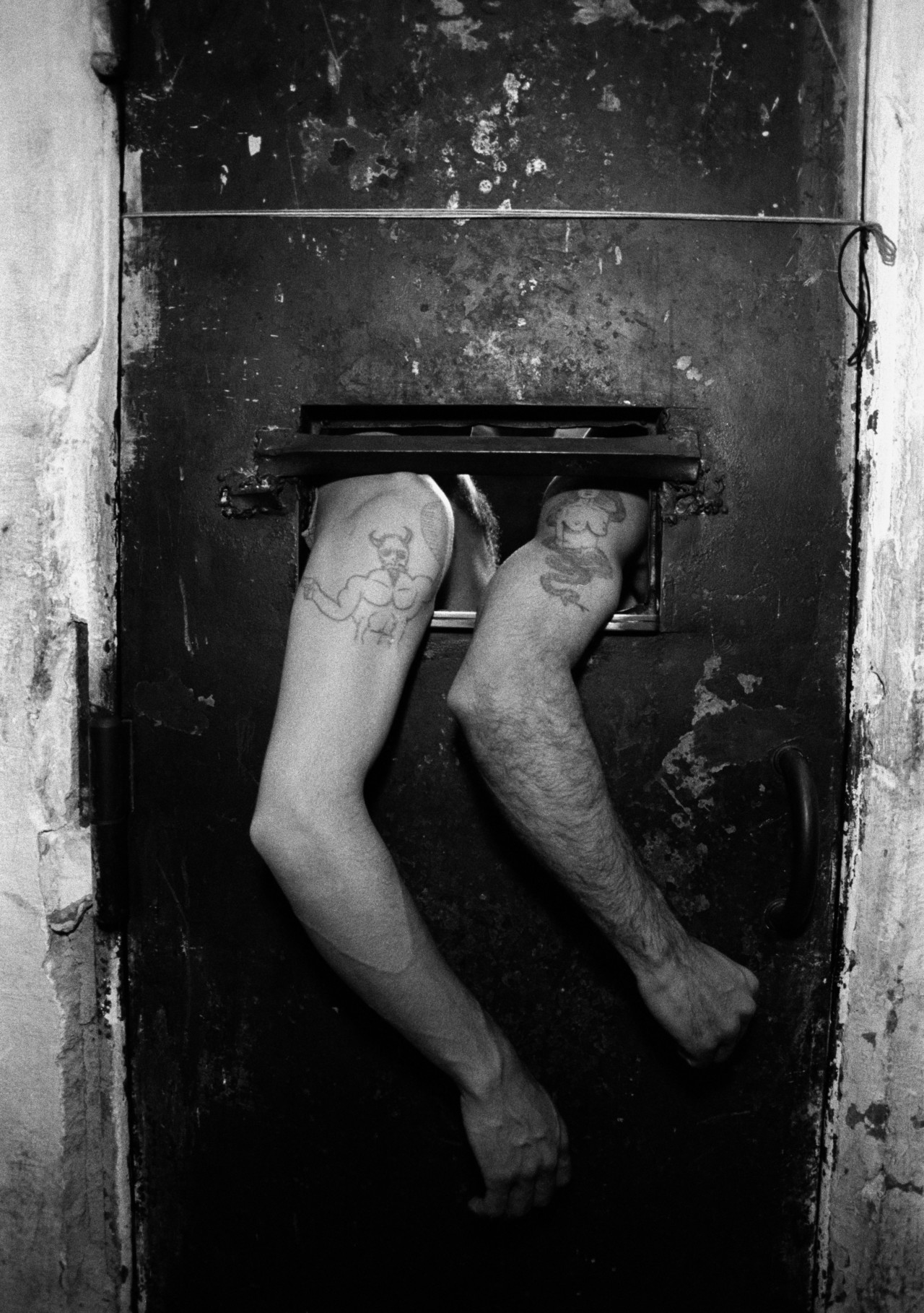

This sense of solidarity and entrapment is also apparent in Alex Majoli’s images from Brazil’s infamous Carandiru Prison. The body here — in a similar vein to that in Cartier-Bresson’s Leesburg picture — interrupts the cell’s door, infringing upon architectural constraint to occupy the space beyond it. Two tattooed arms— presumably male— both create a right angle as they emerge from the small opening in the door, one firmly creating a fist, the other relaxed. What prompted this dual gesture? Did the photographer direct the inmates to pose in this way, or can this be understood as a spontaneous act of physical solidarity? Can we read this as a moment of kinship between prisoners, who share the same daily reality within their cell?

What is the difference between confinement and incarceration? Confinement suggests a state of physical restriction, a lack of agency. Whereas incarceration’s definition is, to a degree more expansive; that isolation and segregation are byproducts of being confined.

Some images in the Magnum archive seem to ratchet-up the physical restrictions upon bodily movement that confinement denotes in its most straightforward sense – the tightness of space, the funnelling of light. They convey the claustrophobic nature of imprisonment.

In Reni Burri’s photographs of a large prison in Nuremberg, West Germany, the hardness of incarceration is documented in a wholly different mode. Cold concrete buildings line up against the left-hand side of the photograph— presumably the prison— while harsh, black barbed wire spirals through the center of the image. The ground is carpeted with snow, evoking the mood of the prison’s barren location. As onlookers we realise we cannot enter; or if we indeed try to, there is a violent boundary which can inflict pain and harm on our bodies.

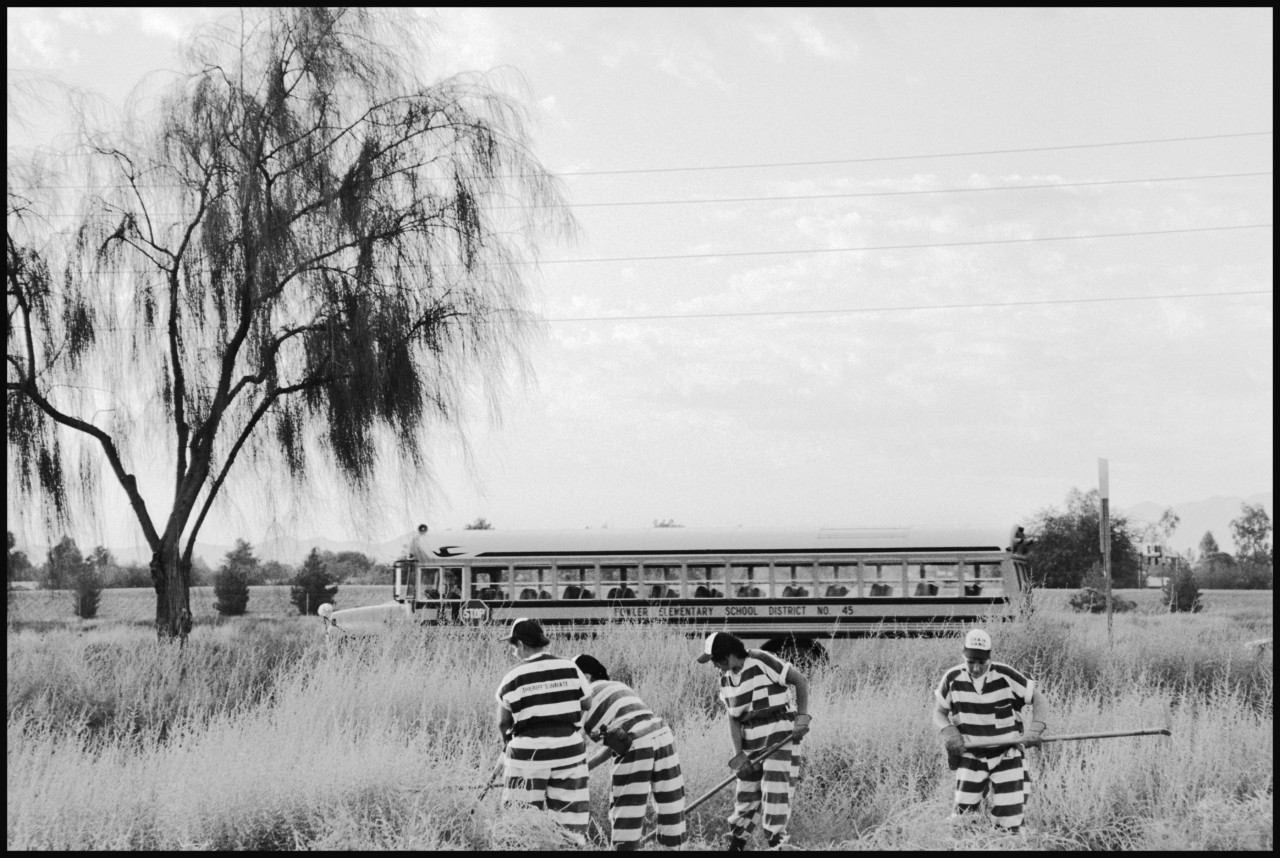

Eli Reed demonstrates the work-labor programmes available for inmates in some prisons in a series of photographs from Arizona. One particularly compelling image depicts prisoners working in a field, wearing the familiar striped jumpsuits and holding rakes. In the background a school bus passes by. To the left, a tree solemnly drapes its branches downward: it seems lifeless, uncared for. There is an elongated sense of time. As the bus passes the workers, they remain fixed in their reality and incarceration. Whether the bus holds other prisoners or children, we do not know, but the viewer becomes acquainted with the everyday reality of imprisonment: confinement as an ordinary state of existence.

‘What is justice and how does it function?’. This is an extensive and ethically charged conversation which is often raised when critiquing the practices of the legal system. On the one hand, prisons are one of the main institutions which deal with justice, yet in the last few years there have been extensive discussions— particularly in the US— around reform. Carl De Keyzer’s photographs of prisoners in Siberia eating at lunchtime evoke a strange sense of otherworldliness. In his work from this project, Zona, captured across Russia, Siberia and Krasnoyarsk De Keyzer also depicts prisoners returning to the camp for lunch. In one image two men sit in front of a bright, almost voluminous mural of a cornfield awaiting their food. Neither of their faces can be seen, but there is a feeling of slowing down, taking stock and pausing. This backdrop tells a story and reimagines agency, removing the individual from the identity the prison has assigned them. The infinite, expansive terrain of this landscape presents a glimmer of humanity and freedom for those who are incarcerated, proposing the potential to exist apart from the restrictions imposed by the carceral system.

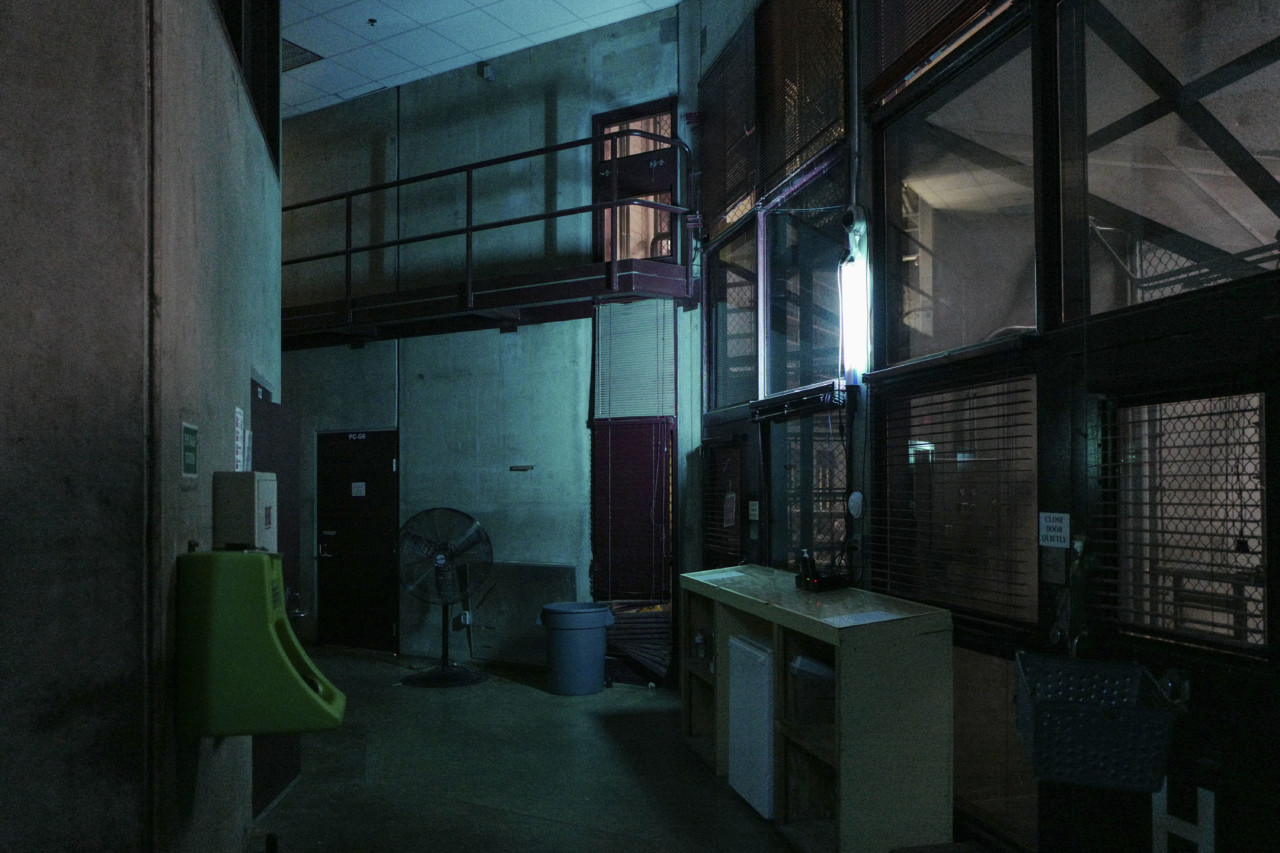

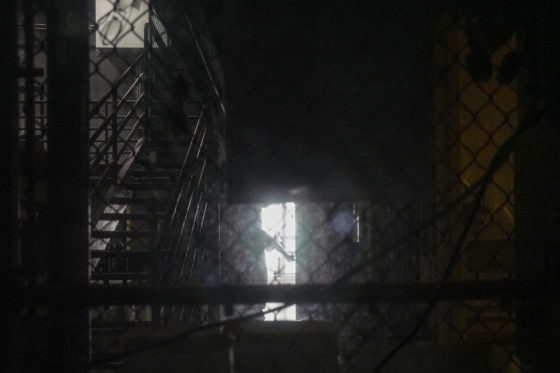

The pursuit of justice is captured by Peter Van Agtmael, who portrays the harshness of a penal system in another context altogether. In 2017 he travelled to Cuba, photographing Guantanamo Bay detention camp. In this series, the notoriously inhumane and controversial prison facility appears intimidatingly industrial. His meditation on the physical melancholy of the architecture of justice poses important questions about the failure of justice in this carceral system.

While working in Guantanamo Bay, Van Agtmael was confronted with ethical issues relating to the photographer’s role when working in a detention center. ‘Everything is very orchestrated and controlled, yet there are many cracks in the facade,’ he says. The photographer explains that even if he had tried to pursue making photographs of prisoners, regardless of the ethics of his approach, he would have failed. Due to Van Agtmael being forced to participate in a larger, pernicious system of incarceration, the photographs do not necessarily break the ‘spell’ of invisibility, but instead, demonstrate the degrees of control when attempting to document their realities as an onlooker.

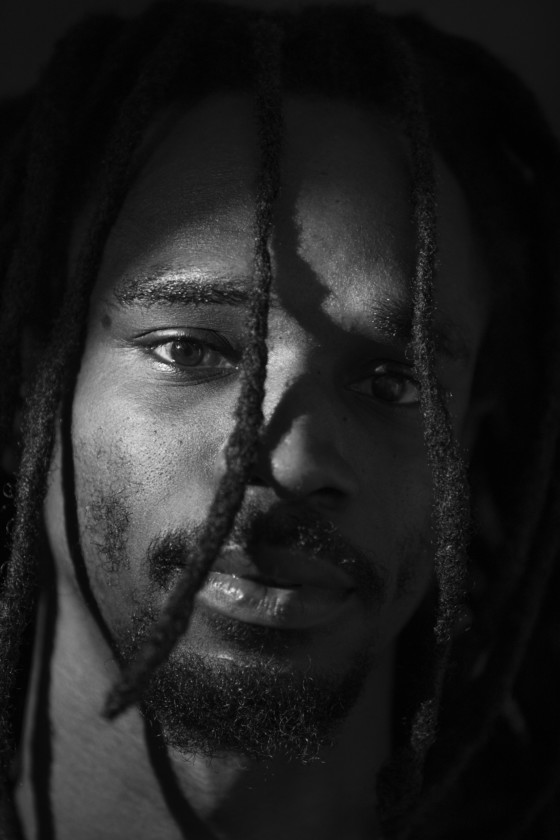

In stark contrast in terms of access, Paolo Pellegrin’s up-close portraits of the occupants of Meux-Chauconin prison in 2016 momentarily remove the human being from its context: the prisoners become men again, freed from their surroundings and the prison’s associations. That is, until their images are juxtaposed with his photographs of the prisons’ barren communal spaces, and stark, imposing structures.

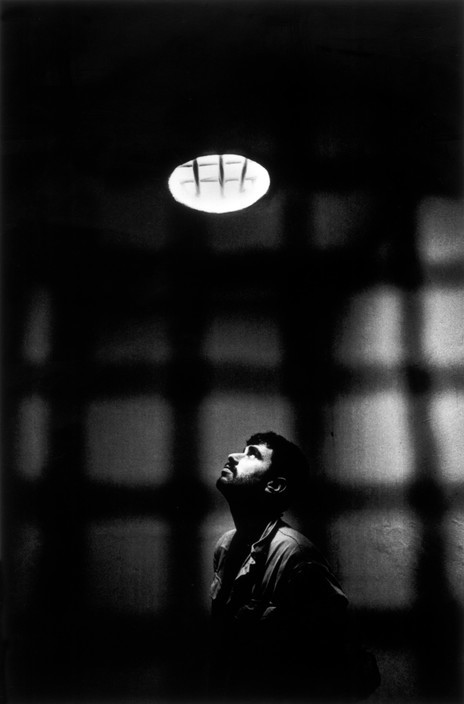

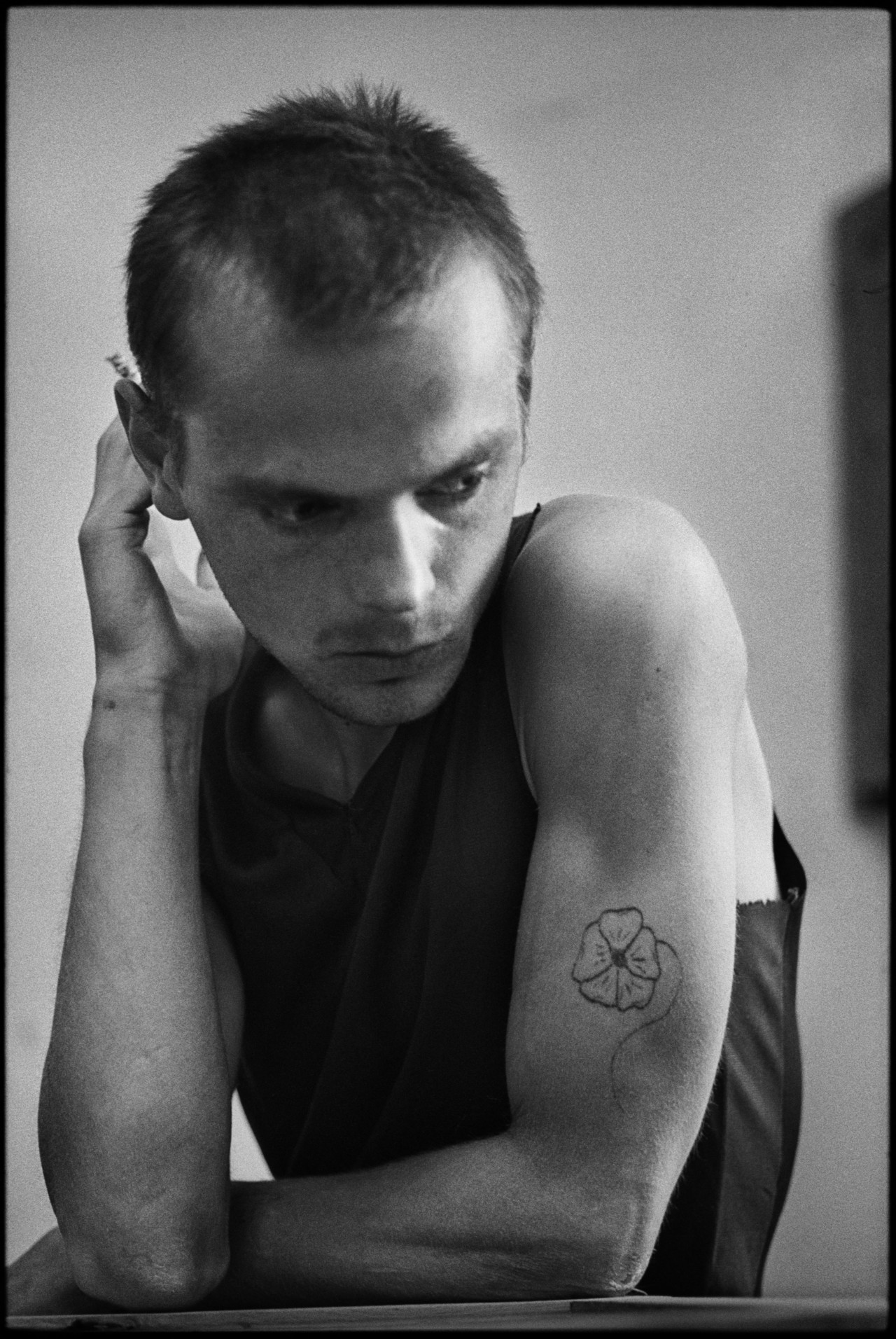

Something of the contrast between the dislocated, reflective individual and their authoritarian surroundings is also to be seen in Jean Gaumy’s portrait of a seemingly pensive convict in Sant-Martin-de-Ré prison, a wilting flower tattooed on his arm. It seems almost strange that this still, personal moment could have occurred in the tightly choreographed, machine-like existence depicted in Gaumy’s other images, taken the same year in Caen, another French prison.

It is perhaps the photographer’s gaze into this territory of incarceration, uncharted for so many of us, which is most alluring to the viewer. Through documentation, the photographer unleashes what cannot be known, and indeed cannot often be seen. Such photographs demonstrate the control of the individual, provide a space of seeming transparency for the public to speculate within, and situate the ideologies and constitution of prisons in a broader context.

These photographs, therefore, reposition this world in a renewed artistic context— breaking with the current reality of carcerality, if only for a moment. Perhaps even in the most controlling and restrictive situations, photography is a process that beckons wider society towards a different perception of inmates, or in Sontag’s words— ‘photographs do something else: they haunt us.’