World Food Day: Working Towards a Sustainable Future

Four Magnum photographers provide perspectives on food supply initiatives

Magnum Photographers

How do you photograph issues around hunger? Gaunt faces, ribs poking through skin, children scavenging in the streets? In the world today, issues pertaining to the supply of food are complex. Around 155 million children under the age of five suffer from stunted growth, while 41 million children are overweight. And after a steady decline over the last decade, world hunger is again on the rise, affecting more than 11% of the global population—or 815 million people in 2016, up from 777 million in 2015.

According to the UN, conflict and climate change are the key factors driving this uptick. Wars nowadays are more protracted and people living in affected countries are nearly 2.5 times more likely to be undernourished. Conflict is compounded by the effects of climate change, which have already fueled war in Syria and the Boko Haram insurgency in West Africa and driven mass migration. Meanwhile, 40% of the world’s hungry people live in more peaceful countries, where food security and nutrition has declined because of droughts or floods, or because of the global economic downturn.

This year’s World Food Day takes the theme of migration and the need to invest in food security and rural development so that people are no longer forced to uproot their lives. Magnum photographers Patrick Zachmann, Alex Webb, Chris Steele-Perkins and Nikos Economopoulos traveled to Colombia, Mexico, Nepal and Tunisia to visit projects run by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) that are trying to build the resilience of rural communities in an era where people are leaving their homes at a greater rate than at any time since the Second World War.

Colombia

One day in 2002, Orlando Ruiz, his wife and eight children loaded a truck and left their home in northern Colombia. “The violence was so intense that I could not bear the situation anymore,” he says. The farmer lost his father to the violence, and worried his children would be recruited by armed forces. But life in the town of Los Palmitos was disorienting—nothing like the life he had back on the farm. “The city—walking up and down the streets doing nothing—is not for us.”

More than 250,000 people were killed and millions displaced in Colombia’s armed conflict, which dragged on for 52 years. Ruiz and his family finally returned home after 11 years, as land restitutions began. A peace deal was signed in 2016, and increasing numbers of displaced farmers are returning.

That hasn’t been easy, but they have received some help from the government, including chickens and cows, farming tools and a solar plant. Ruiz received five cows and a calf; now he has 19 cows. “My wife jokes that I pay more attention to the cattle than her,” he says, laughing. He set up an association with other farmers with the support of FAO.

Patrick Zachmann shows hunger being tackled as a community. His photographs capture the farmers helping each other get plots of land back into shape; women attending courses on management and farming; more than a dozen farmers eating meals together. The FAO-supported project, which has benefited 500 people, focused on integration, reconciliation and the sharing of resources in communities where people who remained or took over land now have to share it with those returning. The support includes training in sustainable agricultural practices, such as raising animals, producing coffee, milk and honey, or setting up infrastructure like a collective irrigation network.

“You know how hard it is to have to leave your land. Being displaced is something you don’t want to remember,” Ruiz says. “After all the suffering, I’m happy and live in peace on my land, with my children. They have all they need to succeed.”

FAO’s project partners are Sweden and the Land Restitution Unit.

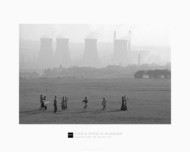

Nepal

In southern Nepal, the wind is getting stronger, less rain is falling and crop yields are suffering. “We have less than a half of the maize we used to have,” says Ashmita Thapa, 21. Last year, her husband—a farmer, who used to grow enough food for the whole family—left to work in Saudi Arabia, hoping he could find a good job. That didn’t happen, and the family struggled to repay the debts they had accumulated to pay for the trip.

Nepal is one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change. In the past few years, long droughts, frequent flooding (because of glacial melts in the Himalayas), unpredictable monsoon seasons and extended summers have all affected crop productivity and forced rural people to migrate. Researchers have predicted that if climate change continues to have such an effect, two-thirds of people in Nepal face risk to their livelihoods.

The effect of hunger that Chris Steele-Perkins captures is there in the absence of men—of husbands, who have gone abroad to seek work. He shows women farmers experimenting with new farming practices, discussing and comparing results; daughters who have never met their fathers.

As part of an FAO-supported project, Thapa—along with around 3,000 farmers—is learning to grow crops better adapted to climate change and better suited to their land. They are also getting support to raise animals. “We have learned many things from the project. If we learn more, it will not be necessary to go abroad,” she says. “I have a great hope that we will be able to work together with our husbands in farming.”

This project is made possible thanks to the support of the Global Environment Facility.

Mexico

It was poverty that forced Paseano Gómez López, a Mexican farmer in Chiapas growing corn and chili peppers, to move to America. Farmers need money to buy supplies to run their farms, but they are often forced to take high-interest loans. If crop yields don’t cover the costs—particularly common in areas with poor soil and high altitudes—they get into debt. Oaxacan and Chiapas states have some of the highest migration rates in the country.

“That’s when you think about migrating—to improve your life, to send your children to school,” says López, who went to Virginia and Florida to pick tomatoes and grapes. He earned $500 a week, sending $350-$400 home to his wife and children.

“There is sadness when you are away. You feel far away from your family,” he says. After 10 months, López returned home to the state of Chiapas and got involved in an FAO-supported project to improve farmers’ lives. He received support to grow better crops, and got some chickens and sheep.

Hunger in Alex Webb’s photographs looks like incredibly hard labor. Couples work the land; tend to livestock and apply herbicide by hand to their crops. FAO has rolled out a project in Oaxacan and Chiapas states, teaching farmers how to use compost to improve soil fertility, as well as offering training in honey production, raising livestock, and setting up greenhouses. López no longer has to borrow money, and his son is now studying at university. “Our life has changed.”

This project is made possible thanks to the support of the Mexican Government, through the Ministry of Agriculture.

Tunisia

Despite having a university degree in mathematics, Said Touety was unemployed for 12 years. He lives in northwestern Tunisia with his 90-year-old mother in Tajerouine, a dry and remote area near the border with Algeria, and was considering migrating to Italy. “I decided to stay in my country and my land. I live with my mother and I am the breadwinner in the house. I cannot leave her alone,” he says, with tears in his eyes. Nikos Economopoulos captured their hunger for a better life.

More than a third of young Tunisians are unemployed, and many leave the country because of poverty and a lack of opportunities; some 1.2 million Tunisians live abroad, seeking work in Europe. In 2016, Touety was one of more than 40 people selected as part of the FAO Rural Youth Mobility project, which aims to provide unemployed rural youth with training and equipment to start their own businesses. Economopoulos’s photographs show some of these new initiatives: quail breeding and egg production; artisanal fishing; production of spirulina, tomato powder, ricotta cheese or organic honey; biological poultry farming; chili and spice mills.

Touety’s father had taught him how to raise livestock but he lacked the resources to do so. Thanks to the FAO project, he learned how to run an organic sheep farm and received a herd of 55 sheep; his cousin also shared some of his own land for Touety to use. “The FAO project gave me a chance. I want to have a lot of livestock and hire a lot of workers to give opportunities to my people.”

The FAO Rural Youth Mobility project is funded by the Italian Development Cooperation and implemented in collaboration with the Agence pour la Promotion des Investissement Agricole (APIA).