Prison Propaganda

Carl De Keyzer reflects on his project Zona - an exercise in photographing controlled environments in the prison camps of Siberia

In 2001, Carl de Keyzer was given authorization by the Russian military to photograph in prisons and former labour camps in the Krasnoyarsk region of Siberia, resulting in images which formed his project Zona. Initially expecting to witness a congruency between the reality of the prisons and the harrowing aesthetics he imagined based on the prisons’ reputation, de Keyzer was surprised to see the surreal vibrance of some of the former gulags, which had been redecorated to resemble “a kind of Disneyland.” Gulag is an acronym taken from Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei (Main Administration of Camps, a government agency), oftenused colloquially in the West to refer to a soviet prison camp. Russian language prefers the more general terms “the camps” – lagerya– or “the zone” – zona. Around the city of Krasnoyarsk, kraslag is the specific term for the sub-Gulag system of camps. Here, Carl de Keyzer speaks to Hatty Nestor about photographing under controlled environments in prisons and the degrees to which imagery and propaganda play a role in how we understand incarceration.

In Jackie Wang’s book Carceral Capitalism (2018) she describes the degrees of manipulation which regulate how the public perceives, compares and experiences prisons. She writes, concerning control and surveillance, that ‘policing represents the inscription of disciplinary power across the entire terrain which is being policed’. Such exertions of power are also enacted through representations of policing, including of inmates and how they are manipulated by authorities and the media. Wang exposes the economic and technological modes by which people affected by the criminal justice system are made invisible; similarly, by analysing photographs, we can define the cultural modes. We discover how images of the carceral realm have to potential to enact the fabrication of the reality they seek to encapsulate.

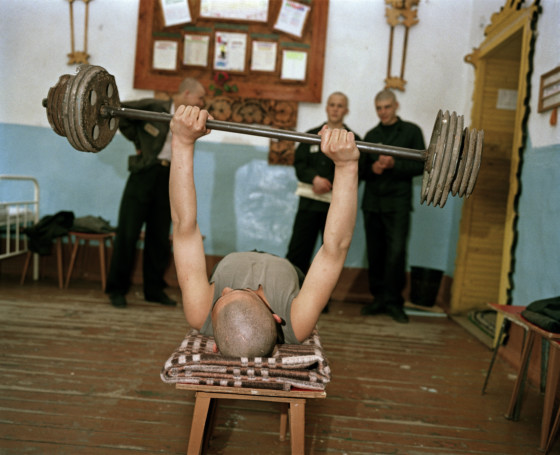

Carl De Keyzer confronts the viewer with these ethical issues in Zona: Siberian Prison Camps. In 2000-2002, De Keyzer spent a total of roughly seven months over three trips, visiting 50 camps. He photographed inmates inside and on the grounds of the prisons in an attempt to both expose the conditions of and destabilize these institutions in the public realm. The photographs are a form of propaganda — prison authorities staged many of the photographs and had an influence over almost all of the scenes De Keyzer witnessed. The intention was to influence public perception of the prisons, whilst controlling the creative agency De Keyzer could exercise. These images of inmates are fraught with an atmosphere of oppression, where the subjects De Keyzer captures subtly display the tension between chosen and staged autonomy. The predetermined set-ups of the scenes were intentionally designed, with the result that the viewer is forced to wonder throughout whether the prisons have been made to look more appealing than how they were in reality. What this series reveals to the viewer are not just the emotional currencies felt by the prisoners, but also the narratives of surveillance and control that De Keyzer experienced whilst completing the project. It is important to note when encountering these photographs, that they are a form of propaganda – a vision exerted by the prison authorities and government themselves. I interviewed De Keyzer in November 2019, to further understand his role in visiting and documenting the Siberian prison camps, and his ethical position whilst doing so.

Gulags were active from the 1920s until shortly after Stalin’s death in 1953. They functioned as forced-labour camps, where those detained were subject to inhumane, labour-intensive work, such as digging, industrial work, and crop maintenance. Under Stalin’s rule, thousands died of disease, exhaustion, and starvation. The camps were famously grim, hostile and labour intensive, often working the incarcerated for long hours, in harsh conditions. When entering the prisons, De Keyzer was aware not just of the current conditions but the histories from the past which they contained. Indeed, it was this horrifying past that prompted the visit, as he noted: “The project started from the mind-boggling fact that before being Gulags from the 1930s’ Stalin era, they were concentration camps. I didn’t understand. Gulags were concentration camps first and now they were ordinary prisons. At the gates you could still see the year they were constructed (1932, 1938…). We would never accept Auschwitz, for example, as a prison”.

Propaganda is both De Keyzer’s tool and the topic of subversion; his work manages to comment upon that which he seeks to dismantle. Propaganda is a theme he has confronted throughout his practice – photographing NATO meetings, North Korea and Capitol Hill. Throughout his work, there is an uncanny sense of invasion; his photographs expose scenes which are politically contested, whilst infusing the photographs with an advertisement-like quality, and vivid color. As propaganda is both his theoretical interest and artisticmedium, the line between the infiltration of cultural manipulation and the generation of it through the photographic image, tread a fine line in his practice.

Yet the photographic image, for De Keyzer, presents problems in and of itself. In seeking to subvert the propaganda of the prisons, De Keyzer was confronted with layers of control. He was caught in an ethical bind: “I felt like I had a moral obligation to do this project right, to not be manipulated by the system because that is what they wanted to do,” he says. The authorities asserted their control through the staging of the photographs – directing the prison staff and commander who accompanied de Keyzer. It was a strange place to find himself, wanting to change representation but not having the complete freedom to do so: “I knew I was possibly being manipulated” he tells me, “because I was there to correct all the images of the old prison system”.

But the extent to which the prison authorities had fabricated the material conditions for the inmates transcended De Keyzer’s control, because he was placed within a setting that had purposefully been orchestrated to appear a certain way. De Keyzer notes that this orchestration was not methodical, and very often set up in what seemed a naïve and ad hoc way. He elaborates:

“Before my visit to some of the camps they had arranged things before my visit. Again, only on a few occasions. Very often they were surprised to see us with the approval papers from the general. Sometimes we had to wait a week before we could go into the prisons. When we got into the prisons we had noticed there was new paint on the fence and flowers on the prison tables.” De Keyzer’s reflections on his time spent at the gulags, published in the appendix of Zona, further reveal the level of orchestration he encountered: “In most camps we could open every door we asked for. In that sense, they showed us everything we wanted to see, except for certain situations. That was something they could arrange as they wished. […] the colonel who was with us understood that I liked people working and doing things, not just standing there staring at the camera […] He’d come into the cell and say ‘You’re being photographed, and you keep on working’ even when they weren’t doing anything, so they’d be given books to read.” De Keyzer recalls that occasionally, a Bible was put on a table somewhere, or they’d have to start cleaning their room, or playing ping-pong.

The viewer is confronted with the harshness of emotion, the uncertainty in the expressions of the prisoners De Keyzer captures. He was never alone upon visiting, accompanied by a commander and a Russian photographer, which posed an ethical tension in and of itself – who controlled the images, and were the prisoners free to pose how they felt appropriate? This conflict runs throughout the series – apparent in the expression of the prisoners and the angle in which they are captured. “You can see it in their faces, they were afraid, they had to obey,” De Keyzer explains, on his encounters with the prisoners.

Despite material changes in the prison surroundings — such as a new coat of paint — initially not appearing to alter what might be at the heart of the emotional qualities of the photographs, they are symptomatic of a larger ideology to render prisons as other to their material reality. Throughout the series, the bright, enigmatic colors are consistently juxtaposed with somber, eerie expressions. In Prison Camp Lunch Time (2000), the tension between the utopian backdrop – a fanatical river with golden grass – hangs behind two men. In front of it, there seems to be a dialogue between two prisoners. The viewer can see a man whose face rests in his hands, adjacent to the camera. There is a feeling of despondency, the backdrop a type of propaganda in and of itself. It reminds us that the reality of prison is far from the painting’s feeling of serenity. Similarly, in Women’s Camp 22 (2001) a group of female inmates sit in a cinema-like setting on bright orange chairs. There is a consistency in their postures, expressions. They all seem somewhat lifeless, indeed almost corpse-like, as they all congregate as an audience. Again, the scene is offset by a natural backdrop of trees and sky – less fanatical than the lunch scene – but its presence reminds the viewer that the prisoner’s experience of the outside world is distant. Yet the insight De Keyzer reveals alters the tone of the picture somewhat: “In this scenario, the room was dark, the lights were out so the prisoners could listen to ‘therapeutic’ music and see disco lights. Most had their eyes closed. I used a flash. In both photographs, we are reminded of the contradictions of documenting controlled prison environments.

The images prompt us to consider the impact of De Keyzer’s photos, as one of the few people who have created a visual history of the prisons. What ethical responsibility did De Keyzer bear as a documenter? Would documenting the camps further the problem of propaganda, or subvert it? Prompted with the choice, he explained:

“When you realise this you have two choices, either to say, no I don’t want to participate in this or you continue, going inside and trying to take advantage of the system which is taking advantage of you. It was a game that worked each way.” In his book, De Keyzer speaks of how this decision influenced his visual approach to the photographs, “I decided to use colour.… there wasn’t even a possibility to get the real situation. I don’t think so anyway. I never saw any really hard situations like torture.” Reflecting on this, De Keyzer also notes that he chose color as a way to show that the images came from the modern day — “otherwise, nobody would have believed this was 2001.”

He continues: “I quite liked that idea [of game-playing] because I don’t like [to use] mise en scene myself but when people do it for me I never say no. My colleague had the typical Russian habit of many press photographers to set up situations. So either he set up something with the prisoner, or the colonel or bodyguards set up something… in a way it was a double mise en scene.”

De Keyzer witnessed many surreal — and at times farcical — scenes. “I only once saw a tennis court. I asked who it was for. The prisoners, they said, and immediately looked for two prisoners to play the game. Then they had to find rackets for them, which took another half an hour. They seemed happy with that; I asked them where the balls were, but even after another hour’s search, they couldn’t find any. So we had this ridiculous scene with me photographing these two prisoners pretending to play tennis without any tennis balls. It was like a crazy mime scene.”

Through methods of surveillance, punishment and government control, institutional sites have become severely restricted to the public. This is also entwined with the media, its deep-rooted degrees of bias: the images we receive contribute to a longstanding distortion of the lived realities of those in prison. After all, the agency of those on the inside is suspended, and their appearance in the media is subject to how such outlets dictate not only their image but also the language which surrounds the prisoner. Images of lives encapsulate the way that narratives are transmitted and understood, reflecting not just the day to day realities of those on the inside but also the historical moment in which they are depicted.

De Keyzer explains it was possible to enter prisons, military sites and even abandoned factories, but the regulations on visitation at the time were minimal. Fifteen years later, he is the only person he knows of who had captured the inside of the prisons. Now, nobody can gain access. “A few years after my visit Putin closed all the camps and nobody could get in anymore. Now it is impossible to do what I did fifteen years ago. I haven’t seen any pictures since then and I heard from other people that what I did back then was impossible now.

When a system collapses there is always a period of lack of control. I think this happened in Russia after the collapse of the USSR. Between 1994-2004 a lot was possible. Visiting all kinds of places that were closed or forgotten. This void, lack of control, is always good timing to do things as a photographer or writer you couldn’t do before. “

One might query when encountering these images if they should be viewed as an extension of a system that hides and conceals incarceration, or a documentation of truth. Or, are they an objective depiction, a demonstration of how systems of surveillance might always sustain a form of propaganda? The ruthless histories which inform these photographs are clearly still evident to the viewer. As are the complications of the ethical terrain that De Keyzer had to tread. Perhaps the images dwell in a strange, intersubjective space, where we can attribute them to neither ‘fact’ or ‘fiction’. Interestingly, De Keyzer had originally anticipated filming the camps, as well as taking photographs, as he felt that moving image had the potential to rupture the propaganda of the camps:

“I had a video recorder when I was there, a mic recorder, etc. I felt so lucky to be there I wanted to record everything. On two visits I tried to interview people and I got some amazing stories. After two visits, I had to choose, I could not make a film and a documentary, etc, I choose photography… In total during the 7 months I had exactly 90 hours where I was in front of my real subject, after being greeted by the commander each time, and drinking vodka for 1 hour. That was not enough to do a video documentary. Luckily I chose for photography or else I would have ended up with nothing final.”

This staticity of photography, the surveillance it enacts, is a profound insight into De Keyzer’s process. As the project drew to a close, he described feeling as though it were “a very tricky exercise, which was about the history of image-making and manipulation. If you look at it superficially, without seeing the layers and depths, you see the photographs as black and white, like an advertising campaign”. When viewing these images, it seems only right to ask, not for whom do they serve, but instead, what is lost and found through the process of their creation? What currently takes place in the prisons which we cannot see, or that De Keyzer was not permitted to capture? Looking at these images requires a degree of sensitivity and caution. To claim a certainty about the lived realities of prisoners based on these photographs would be unethical, and indeed, impossible. Instead, certainty lies in De Keyzer’s ability to capture the complex systems of control at work in the prison, and the ways this manipulation operates.