Feldpost: A Global Vision of the Great War

More than 1,500 photos form Thomas Dworzak’s recently completed project, which delves into the myriad narratives, present-day echoes, and truly international reach of the conflict

Feldpost was the name given to the German military postal system used before, and during, World War I. Thomas Dworzak’s project of the same name has seen the Magnum photographer, over the last seven years, create an annotated image for each day of the Great War – over 1,500 of them in total. These ‘postcards’, with their extensive explanatory notes, represent a vision of the war which conveys it’s truly global nature: a complex picture of the conflict that delves into its far-reaching impact, myriad complexities and peculiarities, as well as its present day reverberations.

Chris Bird worked as a reporter with Thomas Dworzak across the former Soviet Union and the former Yugoslavia. Here, we share a small fraction of the project as Bird – now a doctor specialising in paediatric emergency medicine – reflects upon the Feldpost project for which he wrote the many texts that accompany and elucidate each photograph.

When Thomas Dworzak asked me to write accompanying texts for his Feldpost project I imagined he wanted one for each year of the Great War centenary. With stock images in my mind of doomed soldier poets in the muddy trenches of France, a nod to revolutionary Russia and possibly skirmishes in the Middle East, I thought the project would be straightforward: short notes for “postcards” of our contemporary world shadowed by a past that many of us see now as a distant precursor to World War Two and the decades of Cold War that followed.

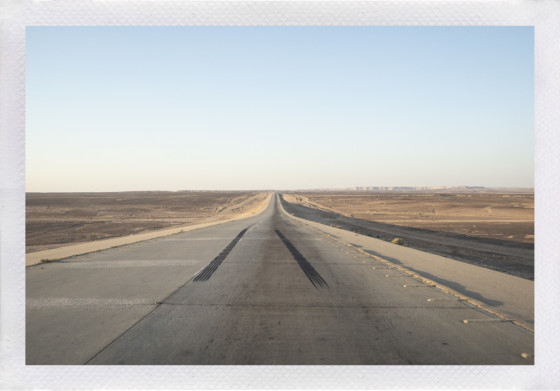

He said he actually wanted 1,568 pictures annotated – one for every day of the war. He mentioned locations that I had no idea had been part of the mechanised conflagration – (Papua New Guinea, Thailand, Brazil…) – while the complexity of regions such as the Middle East, shaped by the 1916 Sykes-Picot line and the 1917 Balfour Declaration, left me slightly overwhelmed.

"Dworzak of course went to Flanders, but he spent most of his time off the well-beaten Great War track"

- Chris Bird

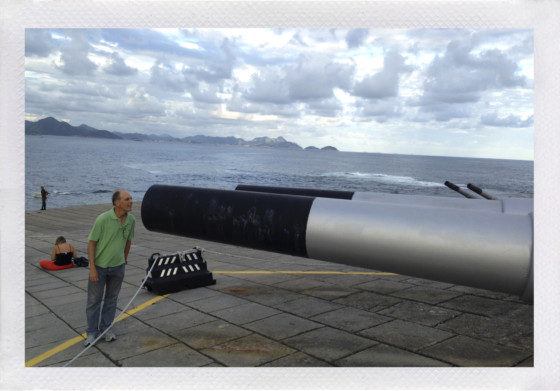

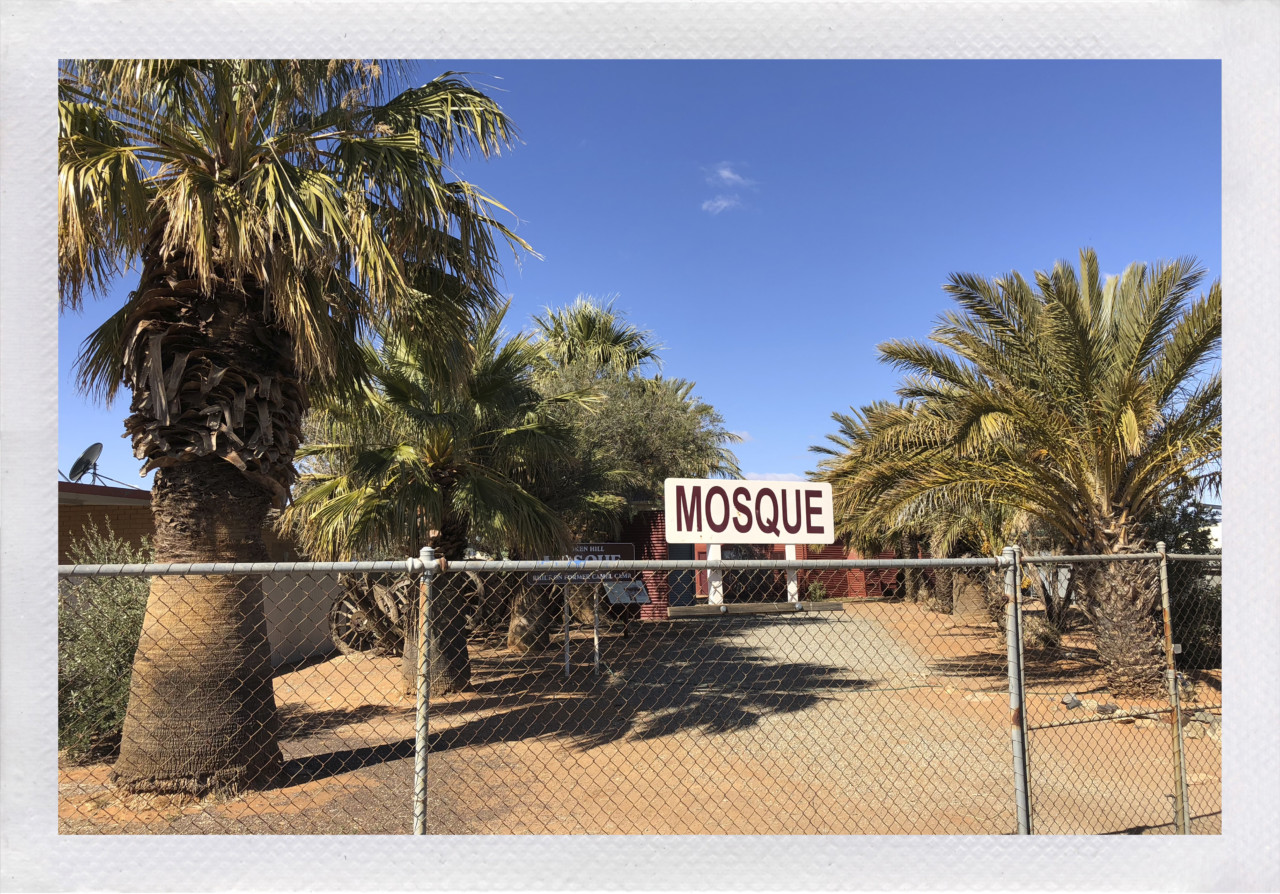

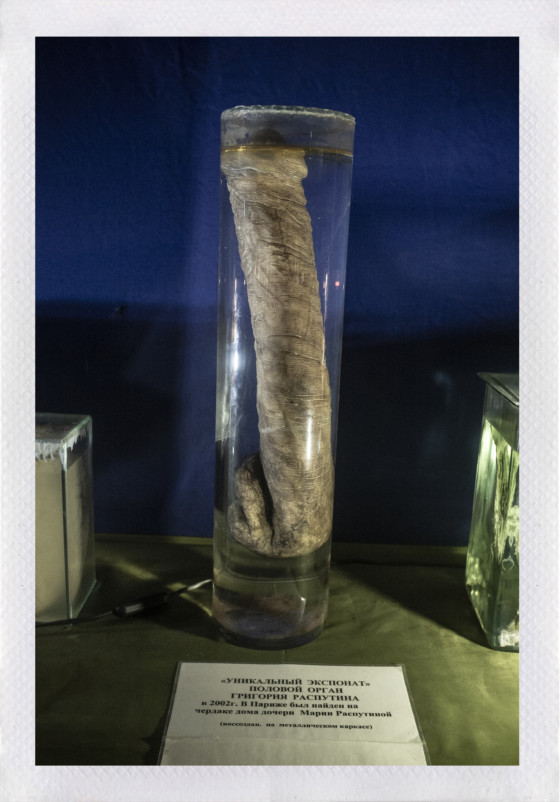

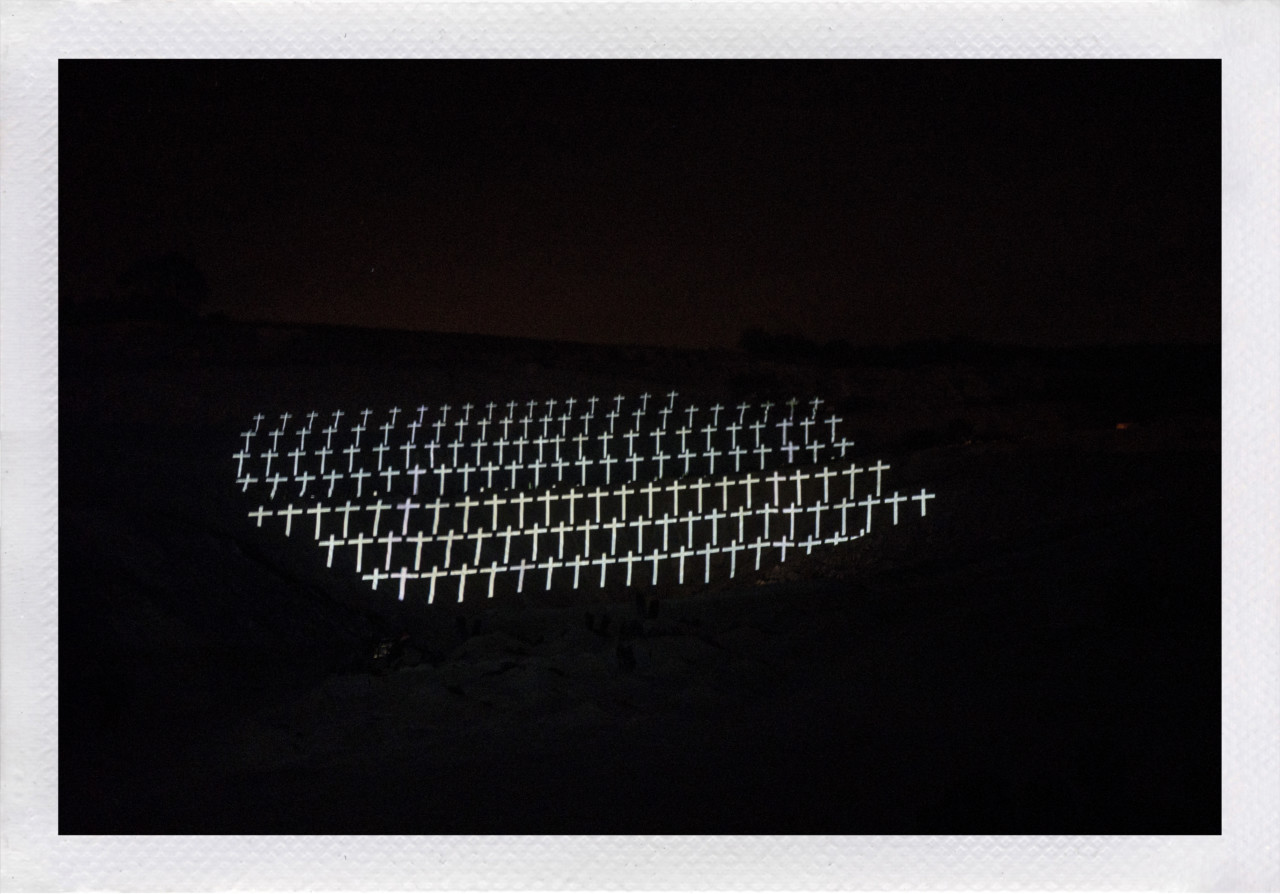

Dworzak of course went to Flanders, but he spent most of his time off the well-beaten Great War track. He travelled to the Australian outback to photograph the site of a forgotten 1916 Jihad attack in Broken Hill and to Japan to cover the story of German POWs captured in China and interned in Bando, where a prison orchestra brought Beethoven’s 9th Symphony to the country – which is still performed annually nearby. He also plays with contemporary myths, for example in his photographs taken around Sarajevo’s Latin Bridge – the Bosnian Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip did not in fact stop for a sandwich at Schiller’s Delicatessen – near the bridge – before assassinating Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie.

“No single person today can master all of the writing available about the First World War, and no one in the future will be able to read at the same speed as new materials appear in print, and in televisual, video, movie or digital form,” wrote the US historian Jay Winter.

Winter’s “big bang” analogy for Great War history outlines four generations of history with ever expanding amounts of material: contemporary and official accounts; those 50 years later which looked more at the social aspects of the war; the Vietnam generation’s deepening disgust with war of all forms; and more recently, the transnational generation, where the fall of the Berlin Wall and the digital era have brought a truly global – rather than solely European – lens to the conflict a century later.

Dworzak takes us to these forgotten places, from photographing sacks of flour in a Beirut supermarket so we remember the 200,000 dead from the Lebanese famine in 1915 (which resulted from Ottoman grain requisitioning, an allied naval blockade and a plague of locusts); to a beautiful blue sea, known as the “Blue Grave”, on the shores of Corfu, where hundreds of Serb soldiers had to be buried for lack of space during a Typhus epidemic; or a Togolese family pausing near the grave of a German soldier killed defending the Kamina radio transmitter in the West African state in August 1914.

Dworzak’s contemporary milieu is haunted. An elderly Jewish man wears a yellow Star of David on a Vienna street, the star recalling not only the Nazi era but that 400,000 Jewish men who were enlisted and fought for the German and Austrian emperors during World War I. The bloody military reversals were fertile ground for simmering anti-Semitism, with right-wing groups in Germany demanding the 1916 Judenzählung (“Jewish census”) to try and show that Jewish men were draft dodgers. The results of the census were suppressed – over four fifths of Jewish men eligible to enlist were already fighting on the frontline, proving their loyalty to the German state.

More ghosts: the carefree stroller posing in front of a camera in Munich’s Odeonplatz, where the young Adolf Hitler was “photo-shopped” into a crowd scene showing him as an enthusiastic supporter of war against Russia in 1914 to boost his patriotic credentials (along with the Iron Cross he was awarded on the recommendation of his German Jewish commander).

"Dworzak brings millions of people back into the story - Asia, Africa, the war on the Eastern front and the crumbling Ottoman Empire"

- Chris Bird

Dworzak brings millions of people back into the story – Asia, Africa, the war on the Eastern front and the crumbling Ottoman Empire. One example: the famine and disease from war-induced shortages that claimed the lives of an estimated 2 million Persians between 1917 and 1919.

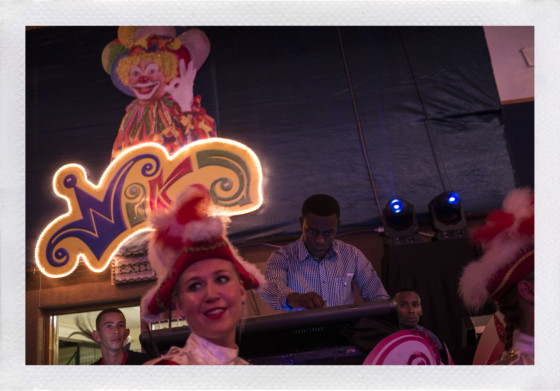

Dworzak’s war is also a diverse one. He turns his camera to the intimate side, the picture of an Amsterdam nightclub poster of a Kaiser in drag reminding us of the first steps towards gay rights during World War One in the form of the German Bund für Menschenrecht (League of Human Rights), which had a 100,000-strong membership.

He also documents the involvement of millions of women in the war, from the struggle to continue the campaign for the right to vote to nursing the wounded, also recalling the major advances in medical care in what was still a pre-antibiotic era.

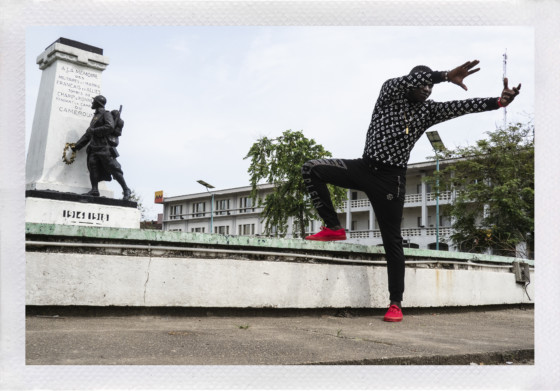

He photographs India Gate in New Delhi, which stands in memory for 70,000 Indian soldiers who lost their lives in France and the Middle East – over a million Indian soldiers served in the war. Dworzak’s pictures from across Africa show us an imperialist war that cost the continent over two million lives, not only in combat casualties but also as a result of hunger and disease. The photograph of portraits of colonial troops awarded the Legion D’Honneur remind us that France used more African troops than any other country – 450,000 – who were often viewed as little more than cannon fodder. Addressing the French senate in January 1918, French premier Georges Clemenceau declared: “I would prefer that ten Blacks are killed rather than one Frenchman.”

From there it is only a short distance to the German genocide against the Herero and Nama peoples in modern-day Namibia in 1904-08. Dworzak picks up the trail, showing old black and white pictures of German soldiers in Namibia as part of an exhibition in Rwanda’s Genocide Museum in the capital Kigali. Crushing a rebellion against German colonial rule, Lieutenant-General Lothar von Trotha, wrote: “I believe that the nation as such should be annihilated.” Rwanda itself was a German colonial possession at the outbreak of World War One but fell to Belgian control in 1916. The genocide against an estimated one million Armenians under Ottoman rule in 1915 is still unrecognised by several states.

Dworzak’s pictures of African Americans waving the Stars and Stripes at a Veterans Day parade in downtown New York tell us that World War I presented African Americans, subjected to segregation laws and racist violence, with a dilemma: whether or not to serve in the US armed forces. Seen as an imperialist war by some African American leaders, others, such as William Du Bois, one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, saw it as a chance to demonstrate their “unfaltering loyalty” to their country.

While 380,000 African Americans were called to serve, over half of them in France, soldiers and officers were still trained at segregated camps. Du Bois wrote of his community’s task after the war, “by God in heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.”

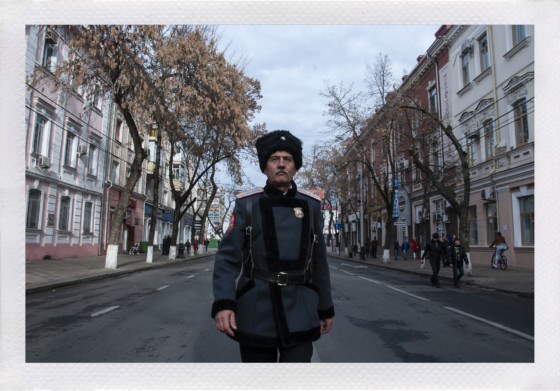

Dworzak’s odyssey also underlines the Great War as a modern phenomenon, an international crisis, according to historian Christopher Clark, brought about in part by the deniable, cross-border terrorism we both witnessed decades later as journalists in the former Yugoslavia (echoing the shadowy, Serb ultranationalist “Black Hand”) and which Dworzak went on to photograph in modern-day Iraq and Afghanistan.

Some of his images seem commonplace – a rack of newspapers, for example – until you realise that the Spanish ABC newspaper was the first to openly report the influenza pandemic. The pandemic was dubbed the “Spanish flu” only because censorship elsewhere suppressed news of the outbreak.

"Dworzak’s use of humble postcards to carry his images puts this overwhelming and tragic story into tangible and human focus"

- Chris Bird

During World War One, thew Feldpost military postal was a crucial link between combatants and their loved ones far from the front. According to historian Martha Hanna, the German postal service moved 7 million letters and parcels between soldiers and civilians a day (the French sent around 8 million a day, with British soldiers sending up to 2 million letters and postcards daily by 1917).

Dworzak’s use of humble postcards to carry his images puts this overwhelming and tragic story into tangible and human focus but loses nothing of its complexity and global scale.