When Water Rises: A Journey Through Turkey’s Drowning Landscape

Turkish Magnum photographer Emin Özmen travels through South East Anatolia, glimpsing the remains of villages submerged by the region's monumental GAP dam programme, and visiting those next on the list for eviction for the last time

In blazing sunshine, I drive towards the Keban Dam, the starting point of a journey along the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, whose abundant waters catalyze both lusts and tensions in the region. These rivers irrigate much of South-Eastern Anatolia, before crossing into both Syrian and Iraqi territories.

The rivers, which flow without taking borders into account, create a situation of interdependence between these countries. Turkey, home to both rivers’ sources, is highly dependent upon the energy industry, and has sought – since the 1960s – to take advantage of the incredible potential of these waters.

Thus the “GAP” project was born. The Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, or Southeastern Anatolia Project, consisted of the construction of 22 dams (19 of which were to be coupled with hydroelectric power stations) and promised the irrigation of 1,800,000 hectares of formerly arid land. GAP covers eight provinces: Adıyaman, Batman, Diyarbakır, Gaziantep, Siirt, Şanliurfa, Mardin and Şırnak, all located in the basins of the Euphrates and Tigris.

The project nominally aims at the development of a poor and underdeveloped region, at the initiation of a revitalization of its economic and social life. GAP’s political aspect is less explicit, but very real: it is also about the further integration of this vast, Kurdish majority territory, into the state of Turkey.

Until now, the project had seemed both familiar and distant to me. It is the pride of a whole segment of the Turkish population, we studied its myriad benefits during geography classes until I was in high school. Yet I have been to South East Anatolia many times, and never documented the region from this perspective.

"Turkey, home to both the Euphrates and Tigris' sources, is highly dependent upon the energy industry, and has sought - since the 1960s - to take advantage of the incredible potential of these waters"

-

On my way to the Keban Dam, the first step of my journey, I start to understand the scope of the project and its consequences. The kilometers pass by and the hilly lands of ochre and orange shades give way, little by little, to sandy ground, scattered with small rocks. Not a tree, not a plant, not a blade of grass, not a living soul is visible. Only desert. But then, after about fifty kilometers, I see some fruit trees emerging. The green spots become less scarce, some houses are visible here and there.

Suddenly, at a bend in the road, an impressive stream emerges under a massive bridge. A magnificent restaurant, in a suddenly lush setting, welcomes many families who have come to taste the carp, a fish emblematic of the region. Before being able to stop here, a security checkpoint brings me back to reality: I am in a sensitive area. The ID check is brief and courteous. I take a break in this restaurant before continuing my journey along the water, that would not leave my side for the rest of my journey.

A few hundred meters further, along a winding road overlooking the valley, I see a couple taking a picture and discover the incredible view of the Keban dam, the first in a series built on the Euphrates, completed in 1973.

"The Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, GAP, consisted of the construction of 22 dams and promised the irrigation of 1,800,000 hectares of formerly arid land"

-

I cross the Euphrates by boat, the fastest way to reach the opposite bank. I am astonished by the sweetness of life that reigns here, despite the relentless heat and the numerous checkpoints located at both the entrances and exits of the piers. On board, cows and pedestrians mingle as the buses and cars discharge their occupants. The decks slowly fill with locals. They are making the most of the crossing, taking photographs and chatting over tea. Fishermen greet us from their small craft. The landscapes are beautiful, the water limpid.

Reality catches up with me when I start talking with the inhabitants of the villages that punctuate my route. While I enjoy the tranquility of the riverside, I meet an angler. He tells me with a sad smile that under these very waters, which I had been admiring, lies the village where he was born, not far from the new town of Samsat.

There are no visible sign of this village’s existence today, and yet the man’s sense of desolation strikes me, reminding me that the GAP region is full of stories like his. Stories of lives and memories swallowed up.

"The remains of a sunken village nearby make me realize that the process is inexorable. Of this seventy-five-house village, there is almost nothing left"

- Emin Ozmen

Samsat was built in the 1980s to rehome the inhabitants of the ancient city of the same name, submerged by the waters of Atatürk Dam’s reservoir, completed in 1989. The “new city” of Samsat has been hit by two consecutive earthquakes – the last of which occurred in April 2018. More than 3,000 homes were seriously damaged. The government has started the construction of 403 new homes, meanwhile families are living in a camp of prefabricated buildings. Fate strikes hard.

I continued toward the Atatürk Dam itself. It attracts visitors who gaze upon it from a café offering an impressive panoramic view. At the entrance to the restaurant is a monument, erected in homage to the workers who died during the dam’s construction. 28 names are listed here, but final totals vary, with some articles citing 40 fatalities.

70 kilometers further down the banks of the Euphrates, the pretty village of Halfeti appears. Despite the charming stone houses, the village is dying. Following the construction of the Birecik Dam downstream and the flooding of the area in 2000, its inhabitants were evacuated. They now live eight kilometers away from this quintessential village, in new apartments built on the top of the hill. It is called the “new Halfeti”. It is soulless, arid, sorrowful.

But it is the neighboring village of Savasan, now only accessible by boat, which attracts the attention of most visitors. More than 200,000 people come, every year, to admire the town’s minarets, just visible now, poking above the waterline. The rest of the has city disappeared. Children playing in the water while standing on the roof of the village’s mosque, offer a surreal vision.

The Birecik dam’s construction also drowned archaeological sites and the ancient cities of Zeugma and Apamea, causing a huge scandal at the time. İn 2000 The New York Times ran an article under the headline “Dam in Turkey may soon flood a ‘2nd Pompeii’“, shortly before the sites were submerged. But through my meetings with people over the years, I’ve noticed that there’s only one name on everyone’s lips when it comes to GAP: Hasankeyf.

"Children playing in the water while standing on the roof of the village’s mosque, offer a surreal vision"

- Emin Osmen

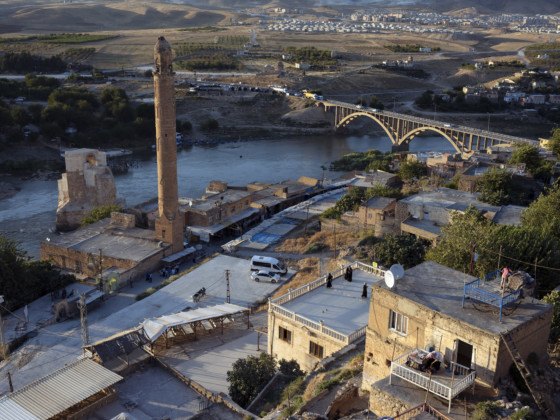

Hasankeyf is a small town, famed for its beauty and history, which has attracted tourists for decades, I had last visited as a student in 2007. The city, whose earliest foundations date back some 10,000 years, boasts an exceptional archaeological heritage: Assyrian, Roman and Ottoman monuments, as well as troglodyte houses, the remains of an ancient stone bridge, and a 12th century mosque.

Hasankeyf is however condemned to disappear under the water due to the construction of the Ilisu Dam on the Tigris River. Once completed it will be the second largest dam in the country. Started in 2006, the project was described by the then Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, as bringing “the greatest benefit” to the people.

In reality, the project is highly contested and plagued by delays, which were exacerbated by the scheme’s European investors (German, Swiss and Austrian) withdrawing from the project, criticizing the failure to comply with environmental standards, and citing concerns over the risk of human rights violations. Iraq’s government has also criticized the construction plans, noting the risk of reduced flow of the Tigris to already-parched areas of Iraq.

The Turkish Government wants to complete the project at all costs. Arguing that the initiative proves that, “the south-east is no longer abandoned”, it will also allow the government to exert pressure on the Kurds, who are a majority, in the south eastern region. The construction site extends to certain mountain corridors used by Kurdish fighters, and in this respect the Ilisu dam Project appears to also be an instrument in the ‘fight against terrorism’. The Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, which is listed as a terrorist organization by Turkey, as well as the United States, will no longer be able to operate as easily in the region, with the dam project and associated development blocking easy movement. In this respect the project is a means to regaining control of a region where the Kurdish conflict has simmered for decades.

"The city, whose earliest foundations date back some 10,000 years, boasts an exceptional archaeological heritage: Assyrian, Roman and Ottoman monuments"

- Emin Osmen

While the town of Hasankeyf itself has a population of 6,000 inhabitants, a total of 70,000 people are likely to be displaced from the surrounding area, and dozens of villages are condemned to disappear on the dam’s completion. All of these sacrifices are to be made for a dam whose lifespan is estimated at only 60 years.

It is therefore with a strange feeling of unease that I drive towards Hasankeyf. As I stop to take photos of the mountains from the road a family invites me to drink a tea in the shade on the opposite bank. The crossing, on a makeshift boat, takes less than a minute. The family is originally from Hasankeyf, but some of them live in Batman, a town of nearly 400,000 inhabitants located 40km from the millennial city. When I mention the old town’s fate they seem rather resigned, ready to leave. They are sad, but do not seem angry. They do not dwell on the subject.

I get back to the car and, after 4 or 5 kilometers, the first stones of Hasankeyf stand in front of me. I wasn’t prepared for what I was going to see. The city’s iconic cliffs had been blown up, destroyed with explosives. I no longer recognize the city I had so enjoyed visiting in 2007. The water, once so beautiful, has turned to a dubious brown colourits flow has been considerably reduced. The restaurants and cafés, once so alive, seem to have disappeared. I looked everywhere, but could not find the famous monuments – they are no longer there. The oppressive heat and the swirling dust of the construction site finally lowers my morale.

Yet later, when the heat becomes less overwhelming and the light becomes softer, life resumes along the Tigris and the magic happens again. As is traditional here, some restaurants placed tables and chairs in the water. While children play nearby, families are having tea, teenagers are shooting rifles at glass bottles, men are lighting barbecues.

"Later, when the heat becomes less overwhelming and the light becomes softer, life resumes along the Tigris and the magic happens again"

- Emin Osmen

I talk to some locals. They tell me that for years they have heard rumors about the impending arrival of GAP in the town, without ever believing it. But when the trucks arrived in the city, when the excavator’s echo was heard in the valley, they finally understood that the project was real. They slowly resigned themselves to it.

Hasankeyf has lived on tourism for decades and the resumption of conflict in the region, in 2015, between the Turkish state and the PKK has been fatal to that crucial industry, scaring away the tourists. The economic situation has become very difficult for the city’s inhabitants. The people I talk with are torn. Torn between nostalgia and a desire to move forward. Their lives have been suspended for years, they do not know when they will have to leave or how they will make their livings once the city is gone. Some end up telling me that, at least, they will live in better conditions in the new city.

In fact, the approximately 6,000 people directly threatened by the submergence had their homes bought by the government, which built a new town less than two kilometers away from the old one. Composed of 710 soulless houses erected by the Ministry of Collective Housing (TOKİ), the city’s administrative services have already moved there.

It is here that the historical monuments have been moved. The authorities relocated eight emblematic artifacts to “New Hasankeyf” in an effort to preserve the town’s heritage and keep some grasp over the vital tourism industry. The monuments are now settled in a kind of archaeological theme park – also soulless – in the new settlement, which is yet to be inhabited.

"I wasn't prepared for what I was going to see. The city's iconic cliffs had been blown up, destroyed with explosives. I no longer recognize the city I had so enjoyed visiting"

- Emin Ozmen

In a typical café, where nothing seems to have changed since the 1960s, some men tell me that they understand the importance of these dams for the country’s economy and energy independence. That the exorbitant cost of moving monuments to the new city reflects the importance they have in the eyes of the government. They add that in a region where unemployment is high, this site offers jobs to those who have been hit hard by the tourism crisis. Others would have liked the government to save Hasankeyf, but don’t know if it is technically possible within the GAP plans anyway…

Below, along the Tigris River, under the monumental bridge which characterizes Hasankeyf, small straw huts built on stilts sit, one after the other one. I’m one of the only tourists. A child fishes, a man prays, a pleasant wind blows on the sheets which protect these small cafes from the sun. Only ducks and geese disturb the tranquility.

Hasan, the owner of one of the huts, has been working and living here for 19 years. He doesn’t know what he’ll do once the city is swallowed up. City officials told him not to worry, that thanks to the rising waters he will be able to open a new café, in the new city. He gets upset explaining to me that the offer is not comparable, there won’t be this view, these grapes, nor his precious fig trees from which he collects fruit every day. He is tired of not knowing what tomorrow will bring.

"The people I talk with are torn. Torn between nostalgia and a desire to move forward"

- Emin Osmen

Ahmed, a farmer from Hasankeyf, tells me that he regrets not being able to unite residents in opposition to the scheme. Their voices might have been heard en masse, but for the fact – he explains – that many men in the city are actually working on the dam, because they have no other source of available income. “They broke Hasankeyf’s arms and legs and now they are destroying its heart,” Ahmed tells me, “I cry, but it doesn’t change anything for my city.” Before he leaves me, he shows me photos of his children on his phone. “Who cares about their future? What will their future look like if they stay here?”

In the neighboring village of Keşmeköprü, I meet four young men who go out every day to savor freshly picked melons. They settle down on the side of a cliff to admire the sunset over Hasankeyf. They then become quiet as the honey-colored rays that licked the stones of the millennial city finally disappear.

The next day I meet them again. They invite me to their home for dinner. I meet their family. Without going into details, they tell me that strong tensions exist between the inhabitants of their village and those of Hasankeyf – the two settlements have been vying for tourism revenue for decades. It is therefore not possible for them to move to the new city and as a result they have no idea where they will go once their village also disappears under water. Maybe to a big city nearby: Batman or Diyarbakır.

"I cannot help thinking that it will be an added cruelty for all these people to see their sunken former city every day from the windows of their new homes"

- Emin Ozmen

As I hit the road again, I pass by the “new Hasankeyf” city. I cannot help thinking that it will be an added cruelty for all these people to see their sunken former city every day from the windows of their new homes.

It is difficult for me to accept that Hasankeyf is going to disappear under water within a few months. And yet, as I approach the Batman dam (completed in 1998), the remains of a sunken village nearby make me realize that the process is inexorable. Of this seventy-five-house village, there is almost nothing left. Only two buildings, partly damaged can be seen, including the remains of a mosque where a dozen cows are now drinking. It is a painful reminder that I will never see Hasankeyf or its neighbouring villages again.

I think back to the four young men who sit every evening, savoring their melons, admiring the millennial city, as if hoping to forget nothing of its details, colors, sounds, or its history. Their history.