Alec Soth: Cleansing the Visual Palate

Alec Soth's new book, "I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating", sees the photographer return to his photographic roots and seek out intimacy with his subjects above all else

A few years ago, Alec Soth started meditating. As well as an increased sense of wellbeing and calm, his meditation had another benefit. “I had an experience where I saw the connectedness of things,” he says. The sun on the grass, the grass in the earth, the earth falling into the water, it all begin to join up, and with that joining up came a new way of seeing and being.

The ‘experience’, came after Soth had completed Songbook and Gathered Leaves, photobooks of large-scale projects where Soth’s images fitted into grand photographic narratives, where the small pleasures of the connectedness of things were sacrificed to the epic sweeps of the essential narrative. That way of working was about to come to an end.

Soth stopped travelling, he stopped photographing people. Instead he stayed at home, happy to experience the pleasure of being with people without the camera there to create a barrier.

“Partly it’s my fault because I created those expectations because of the kind of work I made. It’s like if you’re a writer and you’ve written a big novel, maybe you should just relax and write a few short stories or poems and not take yourself so seriously all the time.”

"Soth has made images where the people he photographs blend into interiors, where eyes glance, hands reach, where there’s intimacy"

- Colin Pantall

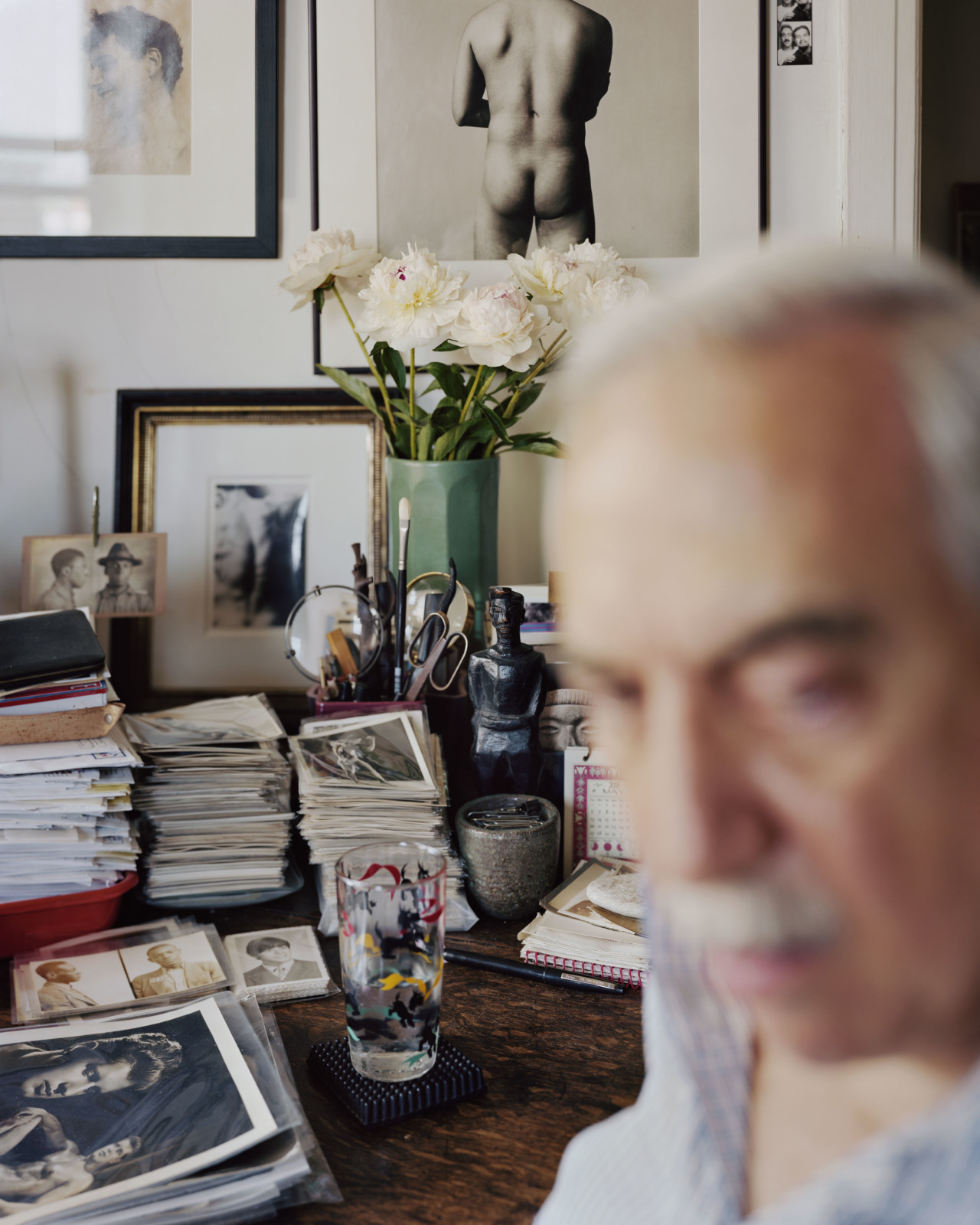

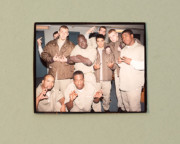

I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating is result of that new way of seeing, that relaxation. It’s a return to photographing people, but without the grand narratives of Sleeping by the Mississippi or Niagara. Instead of some overarching thread, Soth has made images where the people he photographs blend into interiors, where eyes glance, hands reach, where there’s intimacy, awkwardness and a quiet presence that is not overwhelmed by the photograph becoming a monument.

“The root of all this was a very positive feeling,” says Soth. “I felt refreshed and rejuvenated. I wanted to bring that into my photography. I didn’t want to complicate my photography with big narratives and complexity. I wanted to keep it simple and have portraiture experiences.”

“A lot of this work is a return to my roots as a photographer. It is a cleansing of the palate, a cleaning of the system and getting back to this fundamental experience of being with another person, looking at them, wondering what’s going on inside them.”

"I’m responding to that book that’s on the shelf behind them, or the light that’s coming through the window"

- Alec Soth

In that sense, that return to the roots of photography is like a regaining of visual innocence. It’s the question of how can you photograph without the imperatives of the gallery, the photobook or the editorial intruding. It’s the question of how can you photograph with an innocent eye, especially when your eye is manifestly not innocent.

“There was a period after college when I realised that so many of the photographs I love are of people,” says Soth. “I decided to teach myself how to photograph people so I started these exercises with a 4×5 camera to photograph people. I told myself at the time that this is not a project, this is not going to be a show. It was just practice of encountering people and it’s funny because looking at those pictures now, there is a lightness about them because they’re not burdened with the agenda of a project.”

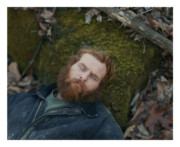

In the same way, the portraits in I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating have a lightness about them. The first picture is of the dancer, Anna Halprin. She appears seated on a carved wooden bench. The light pours in through one window, foliage from the overhanging branches of a tree blurring the scene. It’s shot through a window, the inside merges with the outside, and Halprin merges with both. She is in and of the place.

This was one of Soth’s early pictures, one where he found his “sweet spot”, a spot where he is not determining how the person photographed is seen, but rather they reveal themselves through their connectedness to the world around them.

"How can you photograph without the imperatives of the gallery, the photobook or the editorial intruding?"

- Colin Pantall

All the pictures were made inside, with Soth responding to the different elements in the room that help make the person who they are. “It’s not in a studio. I’m responding to that book that’s on the shelf behind them, or the light that’s coming through the window. Every picture is made through a room. But sometimes they are made through windows and there’s a bit of a release. I’m such a sucker for windows in photography (Szarkowski’s Mirrors and Windows and all that) because they’re such a visual metaphor for photography. The camera is a box and the lens is a window so there is this element of separation. This glass that separates you”

“The fascinating thing about reflections is that a window is a mirror. And that’s the same with a camera. You are looking out at the world, but at the same time you get glimpses of yourself. That’s the space I like to work in, between outside and inside, where I’m looking at other people but it’s also about myself.”

"You are looking out at the world, but at the same time you get glimpses of yourself. That’s the space I like to work in, between outside and inside, where I’m looking at other people but it’s also about myself"

- Alec Soth

In that sense, the book is about who we are when we photograph somebody, who the person photographed is, and how they reveal, conceal or perform themselves in front of the camera. It is about a metaphorical removal of the photographer’s self to allow the person photographed to enter the picture.

That removal of self is also perhaps an attempt by Soth to bridge that sense of detachment he feels. “I have an exaggerated sense of separateness. The world’s out there and I’m in here and there’s this gap between us.”

That gap is also apparent in The Gray Room, the Wallace Stevens poem from which the book gets its title. It goes like this:

Although you sit in a room that is gray,

Except for the silver

Of the straw-paper,

And pick

At your pale white gown;

Or lift one of the green beads

Of your necklace,

To let it fall;

Or gaze at your green fan

Printed with the red branches of a red willow;

Or, with one finger,

Move the leaf in the bowl–

The leaf that has fallen from the branches of the forsythia

Beside you…

What is all this?

I know how furiously your heart is beating.

"It’s austere but there’s so much beauty in there, things are glittering, and there’s beauty and wondering at what’s happening in this other person. It’s about making do with the amount of connection or disconnection at any given time."

- Alec Soth

“It’s austere but there’s so much beauty in there,” says Soth, “things are glittering, and there’s beauty and wondering at what’s happening in this other person. It’s about making do with the amount of connection or disconnection at any given time.”

“One thing I was thinking about recently was that when I photograph people I’m at a distance. When I reach out I would not touch them so I’m at a not-touching distance.”

Because there is distance, it allows the photographs to breathe, it makes the people photographed become part of the places they inhabit. And because they have produced those places, it’s their home or their studio, they bleed into it and Soth becomes part of it. In the image of the dancer on the chair, his eyes go one way, his body is tense, but then you see his feet on the floorboards, one pointing at Soth, and that’s the connection.

I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating is a return to the fundamentals of photography, to the pleasures of photography. It’s an attempt to touch on how eyes, face, body and space reveal a person’s presence and give an image soul, an attempt that is freed from the burden of having to be part of some monumental project or book.

In one sense it’s a success, a meditation on the intricacies of portraiture, on the little things that make us who we are. In another sense it’s a failure because now it is a book and it will become something else. Alice Munro, the great Canadian writer once said: “I want the story to exist somewhere so that in a way it’s still happening … I don’t want it to be shut up in the book and put away – oh well, that’s what happened.”

Alec Soth’s new monograph, I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating, is published by Mack Books.

Specified images made as part of the Romanias project, Courtesy Eidos Foundation.