Agata

Bieke Depoorter reflects upon her ongoing project, the frustration of trying to ‘capture’ a person with photography, and the demands and extremes of true artistic collaboration

The following article includes images which contain performative nudity.

Seeing is believing, and therein lies the rub when picking up the camera and taking photographs. “I don’t think pictures tell the truth,” Bieke Depoorter says, recognizing the fundamental paradox of art. Representation is not the thing itself, but a world all its own.

Because of this belief, Depoorter takes exquisite care of those she meets. “I want to be with people first as a person, then as a photographer,” she says. “I am really questioning the medium. Why I am doing it? How do you use the people you are photographing, and how can we collaborate with them? How can one photograph or work with ‘the other’ without putting oneself above them?”

These questions are at the heart of Agata, a project Depoorter started in November 2017, as part of the Magnum Paris Live Lab. The Belgian photographer remembers the moment as a dark period when feelings of doubt dragged her spirit down.

But then, one night, a lot changed. Depoorter was invited to visit an infamous strip club in Paris’ Pigalle district. “They gave me champagne all night long. I think they wanted me to strip there,” she recalls. “I really liked the atmosphere. There were not a lot of men. It was a very strange place. The bouncer told me, ‘There’s a girl here. I think you will like her.’”

That girl was Agata, a young dancer, just hours away from her 24th birthday. Their connection was immediate, intimate, and mutual. After hours speaking about art and life at the bar, Agata invited Depoorter back to her home and together they made the very first photograph in the series: a picture of Agata wearing a pink bodysuit in an all-pink room, quietly watching us look at her.

Depoorter realized that in Agata, she had found a rare gem – an elusive, enigmatic spirit whose depth of soul was unfathomable. “Normally I don’t feel the need to see people again. I like the intensity of knowing it is just a short encounter,” she explains. “But I was very intrigued by Agata, I wanted to see her again. We – as photographers – often try to capture the real person and I felt like I didn’t capture her. It was frustrating and fascinating.”

The next time they met, Depoorter gave Agata space to shape their encounter, to lead the way. They walked through Paris at night, taking pictures that would be exhibited the following week at the Spéos International Photo & Video School.

“Agata came to the exhibition in this big fur coat and brought pink flowers for me. She was happy to pose in front of the pictures and talk to the visitors,” Depoorter says.

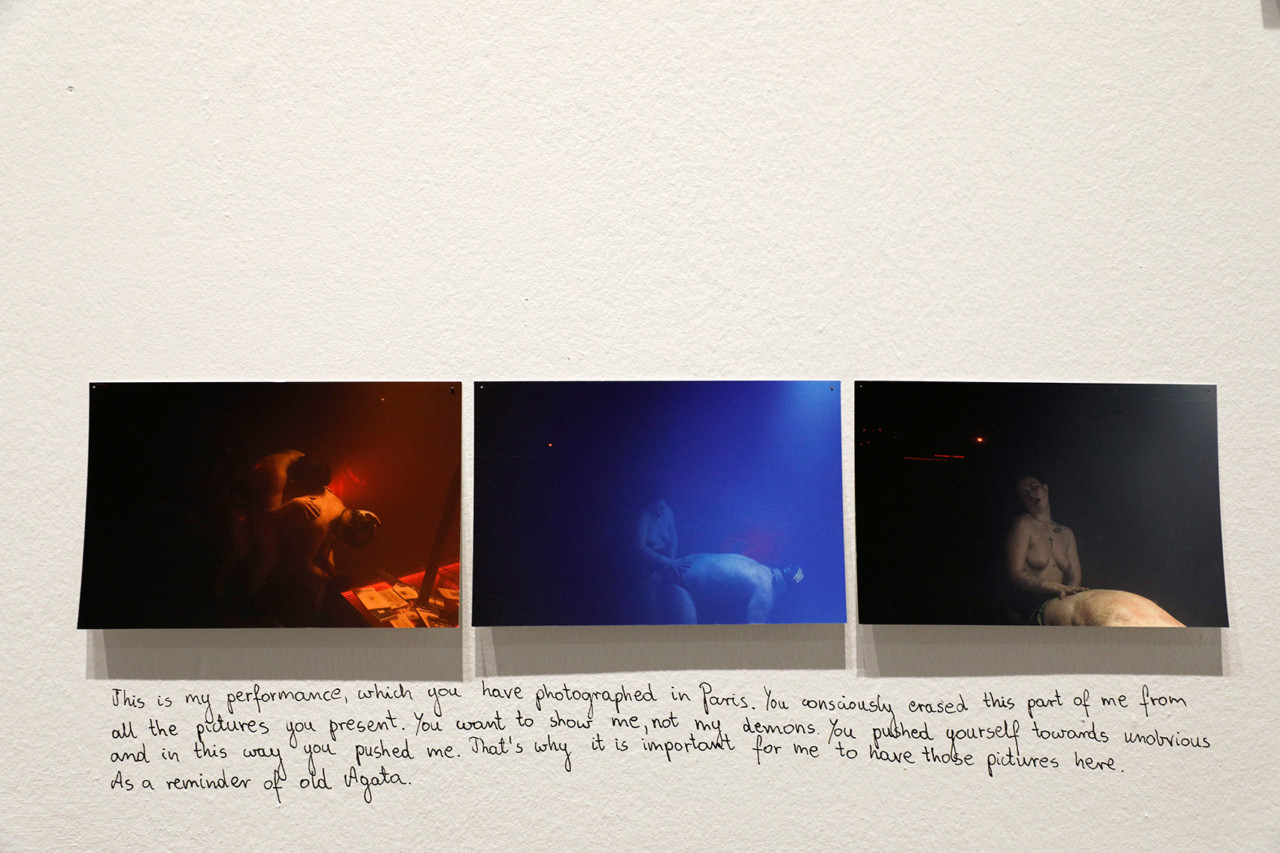

Agata invited Depoorter to photograph her performing before she left Paris. “I didn’t know then, but it was quite sexual,” Depoorter recalls, describing the sight of Agata on stage at a party, penetrating an old man from behind. “After, we talked a lot about this performance,” Depoorter says. “I took pictures of this. We often talk about whether it is necessary to put yourself through pain in order to show if you are someone or not.”

Although Depoorter was leaving Paris, their relationship had only just begun. They decided to continue collaborating and creating a space to explore the existential questions of life and the discovery of the complex layers of self. Over the past year they have traveled to Athens and Beirut together, visited each other – in Paris as well as in Ghent. The pair recently returned from a visit to a Sufi temple in Germany, and are making plans for future journeys that include visiting Agata’s parents in Poland, and going to Morocco for Ramadan.

"In every city, they walk at night under the cover of darkness where the masks of polite society can slip away. Sometimes they walk in silence, with Agata leading the way"

-

In every city, they walk at night under the cover of darkness where the masks of polite society can slip away. Sometimes they walk in silence, with Agata leading the way and Depoorter saying, “Stop,” when the moment is right.

“We often talk about life and searching — for who she is and how she sees herself as the actor in the film, and I too search, we search for each other,” Depoorter says. “I started to photograph her and then it became the constant switch of: what is real? What is not real? Is she acting? I wanted to grab the real Agata, to find her, and she was constantly playing with whether that is possible or not.”

In Agata, Depoorter brings us into their world, using the photograph to explore the space between illusion and truth. As Depoorter and Agata delve into the complex nature of the self, they embrace the ambiguity of appearances while continuously constructing and deconstructing the very idea of what is real.

Together, Agata and Depoorter have embarked on a hero’s journey of challenge and adventure, revelation and transformation, with every stop along the way opening new doors. Before journeying to Beirut, Depoorter visited Agata at her new house , which she squatted in years after an elderly woman named Germaine, the former inhabitant, had died.

"Agata seemed very close to Germaine, sleeping in her room, donning Germaine’s clothes. That night they took photographs of Agata packing her suitcase for the trip - taking almost only clothes that had belonged to Germaine"

-

“That night, we read part of the diaries Germaine had left,” Depoorter recalls. “She was also [writing] a lot about identity, reality, and trying to find herself – sharing quite similar thoughts to those of Agata. Agata seemed very close to Germaine, sleeping in her room, donning Germaine’s clothes. That night they took photographs of Agata packing her suitcase for the trip – taking almost only clothes that had belonged to Germaine. Then a flash of inspiration hit: Agata would travel to Beirut as Germaine and bring one of the diaries with her, in which she could chronicle her experiences and observations. Now Agata’s voice was centered loud and clear, as her words have become an integral part of the story being told.

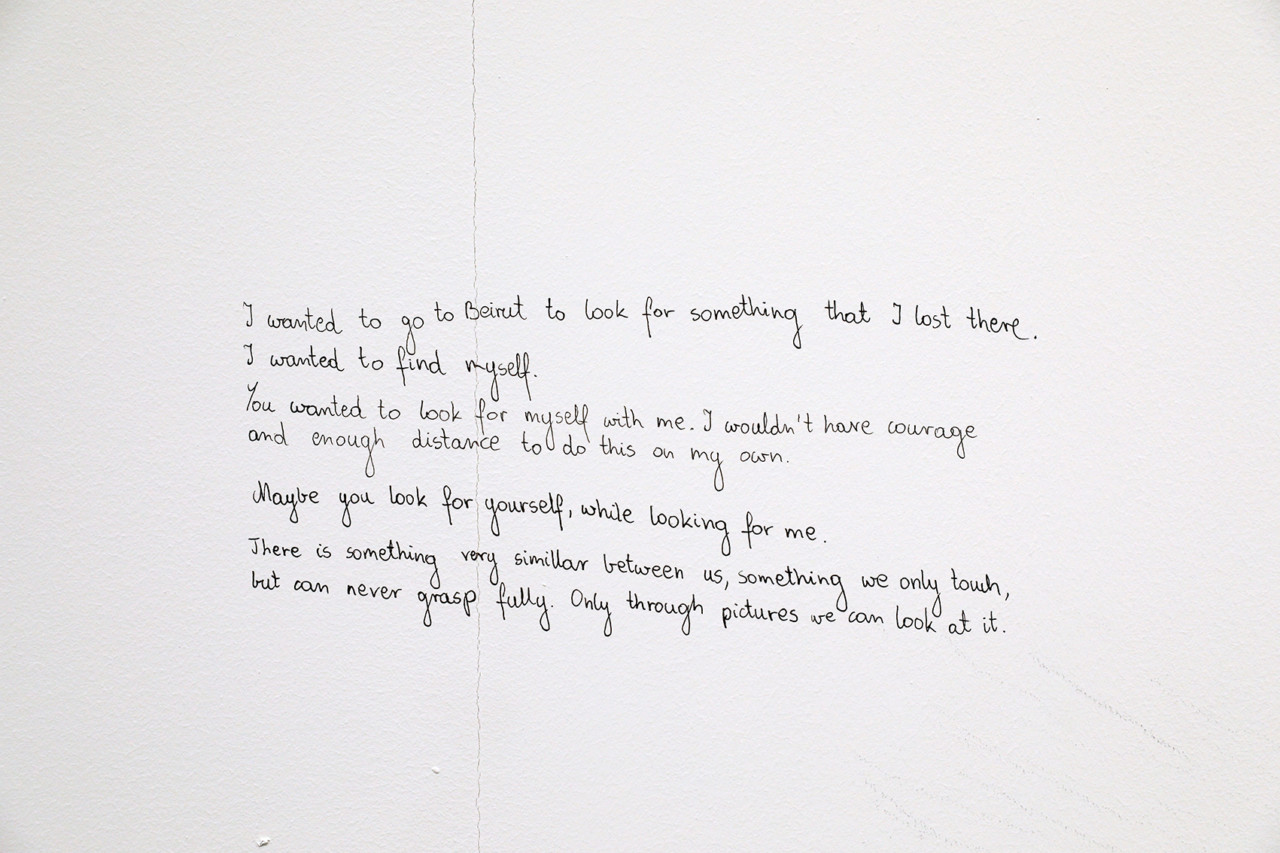

“I wanted to go to Beirut to look for something that I had lost there. I wanted to find myself. You wanted to look for myself with me. I wouldn’t have courage and enough distance to do this on my own. Maybe you look for yourself, while looking at me,” Agata wrote in 2018, on the wall of Depoorter’s exhibition of the work at FOMA Museum in Antwerp.

Indeed, for Depoorter every encounter with Agata was a revelation: of self, of art, of truth — and of the relationship they share. “Beirut was very special. Normally I don’t take so many pictures, but here it was an explosion,” Depoorter reveals.

It was, at this stage, that Depoorter discovered the space where film and photography meet, at the very moment of “Action!” Recognizing that a scene was unfolding, and needed to be captured as it did, Depoorter began shooting a rapid series of photographs which she then printed small and showed in sequence, explaining, “I don’t see them as single images; I see them as six images together. There is no one way in which they work with each other. There are very different styles of how I photograph her.”

"There was a really weird tension between her and the guy, and all of us. I felt she wanted to have power over this man"

- Bieke Depoorter

The pair’s organic, intuitive partnership is renewed by the twin engines of surprise and discovery — perhaps most tellingly one night in Beirut when Depoorter introduced Agata to a man she had met on the street.

“There was a really weird tension between her and the guy, and all of us. I felt she wanted to have power over this man,” Depoorter remembers.

The man cut the pair’s hair, and they went inside to look at the results. “In one of the first pictures I took that night, she started to let the man kiss her breast. I am not sure that this was purely performative, I don’t know whether this was for me, or for Agata,” Depoorter says. “I didn’t want her to do this, but then at the same time she was looking at me like, ‘Do you have the picture?’ It was a strange and special moment,” and, according to Depoorter, it conveyed a great deal about the relationship between photographer and subject.

When the time came to curate the FOMU exhibition, Depoorter showed Agata the photo and then expressed concern about including it in the show, worried people would see Agata as a prostitute. “She told me, ‘No you have to put this picture in, this part of myself, and I like the idea people don’t know who I really am,’” Depoorter recalls.

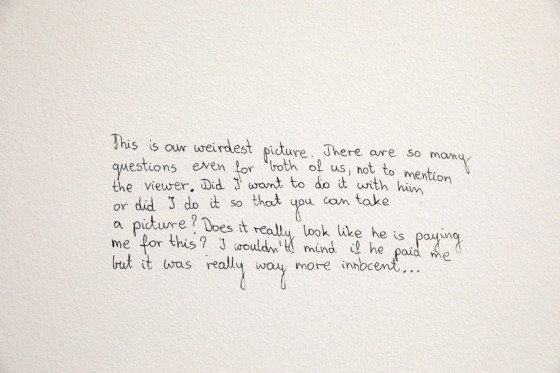

Agata, in turn, wrote a few words next to photograph, sharing her thoughts with Depoorter and by extension, the viewer: “This is our weirdest picture. There are so many questions even for both of us, not to mention the viewer. Did I want to do it with him or did I just do it so that you can take a picture? Does it really look like he is paying me for this? I wouldn’t mind if he paid me but it was really way more innocent.”

"Agata’s words serve to remind us that there is far more to these images than meets the eye"

-

Here, Agata gets to the very essence of the work, revealing the ways in which seeing is more than believing — it can be projection, assumption, and judgment based on their pre-existing biases. In this way, Agata’s words serve to remind us that there is far more to these images than meets the eye.

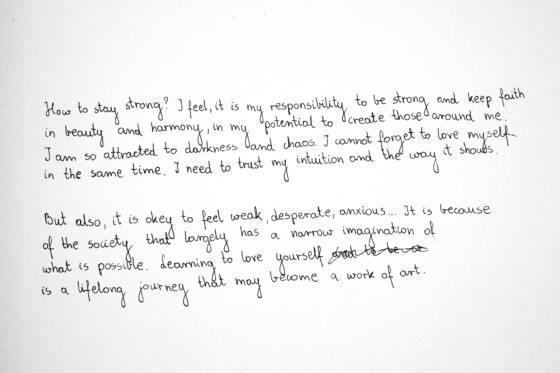

In a letter to Depoorter, Agata explains, “When I met you, I was at the beginning of massive transformations. Starting to see reality differently and to question myself. Trying to understand who I am and how to love myself. The Agata you created when we first met in Paris was fuel for this self-inquiry. You flashed a light on many of my hidden identities. I never though any of them were good enough to be brought to the surface.”

But Depoorter knew, and she believed. It was this faith that has allowed Agata to be the face and voice for the profound questions that stir Depoorter’s soul. “I want her writings to be included because you see how she feels and how she plays with reality,” Depoorter notes. She added that the writing reveals how photography itself is defining and altering their relationship. That Agata is changing because she is being observed, photographed, and that the process of being the subject is changing how she sees herself. “The picture is not the truth — and I am searching too. We try to find this out together.”

In Agata, Depoorter and Agata have found that the key to unlocking the paradox of self is to slowly peel away the layers of ego, belief, and conditioning. In Depoorter’s hands, the photograph becomes the stage where truth and illusion weave a captivating spell. Within this hall of mirrors flashes of reality reveal themselves only to slip through our grasp — but this only serves to heighten our desire for the moment of revelation to come.

A wider edit of Depoorter’s ‘Agata’ project can be seen on Magnum’s archive, here.

Depoorter’s Agata work is included in The Body Observed exhibition, opening at the Sainsbury Centre of Visual Arts on 23 March. More information on the exhibition can be found here.