David Seymour: A Life Worth Living

A celebration of the life and work of Magnum co-founder ‘Chim’ for the 2016 Magnum Seasonal Fundraiser

This year, the Magnum Seasonal Fundraiser is in honor of the agency’s co-founder David ‘Chim’ Seymour (1911-1956). An outstanding photographer, his humanist spirit imbued the agency from its very beginnings. Chim’s empathetic approach to his subjects–from victims of conflict to his ‘Children of Europe’ project with UNICEF–has had a deep impact on how we view the role of photojournalism today, and his legacy has inspired generations of photographers.

The Magnum Seasonal Fundraiser in honor of David ‘Chim’ Seymour runs from Tuesday, November 29, until Sunday, December 11. During this time, we will launch a special series of historic contact sheet prints and fine collectors’ prints on the Magnum Shop. 20% of proceeds from the fundraiser will be donated to an international children’s charity.

Chim’s biographer, Carole Naggar, tells us more about Chim’s life and work.

Dawid Szymin was born in Warsaw in 1911 into a family of Jewish intellectuals. But instead of working as a publisher like his father, he changed path and started taking his own photographs: in 1933, based in Paris, he wrote his childhood sweetheart, Emma “As you know I am not working on the reproductions (lithographs) anymore, I am a reporter, or more precisely, a photo reporter.”1

To match his new life working for magazines such as Vu and Ce Soir, he chose the name “Chim” for his byline. Easier to pronounce, Chim evoked his former name while erasing his Jewishness. It symbolized his identification with a new international and secular milieu, turned toward the values of socialism and humanism.

In 1934 he met Cartier-Bresson. They became friends, and Chim introduced him to a Hungarian émigré, André Friedman, who had taken the name of Capa. They were soon sharing Chim’s studio and darkroom.

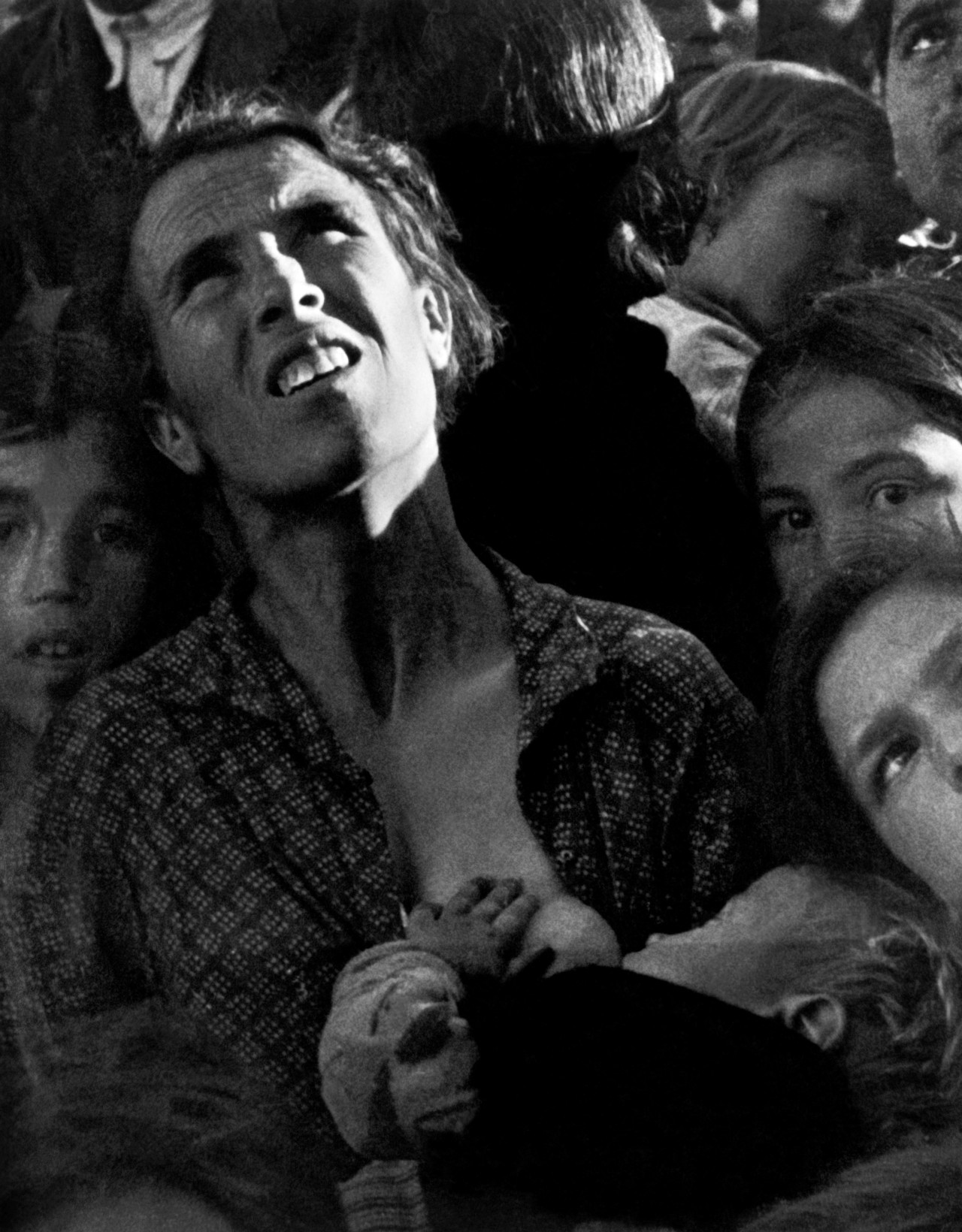

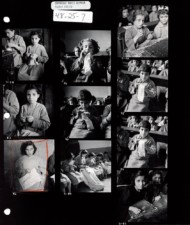

In the spring of 1934, he was hired by the weekly magazine Regards, for whom he covered aspects of France’s political and social life and the beginnings of the Popular Front, a left-wing coalition. In the Spring of 1936, Chim was dispatched as Regards’s ‘Special Correspondent’ to cover the Spanish Civil War–he also persuaded the magazine to send Robert Capa and his girlfriend Gerda Taro to Spain. Among his numerous images is his famous photograph of a woman in a workers’ meeting listening to the speaker in rapt attention as she nursed her child. Like Robert Capa’s Falling Soldier, this picture became an iconic image of the Spanish Civil War.

But by early 1938, the Republicans had lost the war. Chim’s profound sadness and disenchantment are almost palpable in a series of images that show long columns of grim refugees, bundled up in wool covers against the bitter cold, snaking into France through the Perthus pass, their figures blurred by the fog.

In early spring 1939, Match sent Chim on assignment aboard the SS Sinaia, transporting 1,600 Republican refugees to Vera Cruz: the Mexican government was offering them political asylum. Shortly after Chim had landed, World War II started. As a well-known Jew and a socialist, going back to Europe meant risking his own life and endangering his family.

Instead, Chim traveled to New York, where he arrived paperless and jobless. He found a job in a photo lab, Leco. By May 1943, he was an American citizen with a new name: David Robert Seymour. Chim was inducted into the U.S. Army in October 1942, and in 1944, he received an appointment as a photography interpreter. As such, he played a crucial role in the Allied victory.

"Without Chim, Magnum would not have existed, because he drew up our by-laws"

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

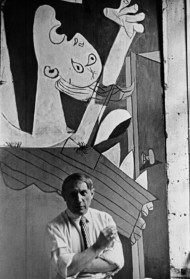

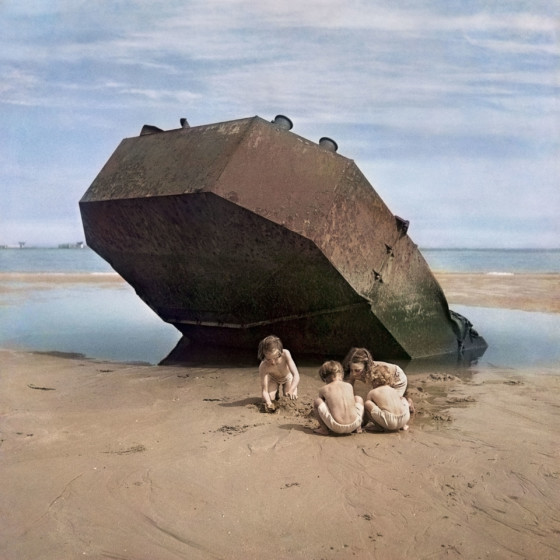

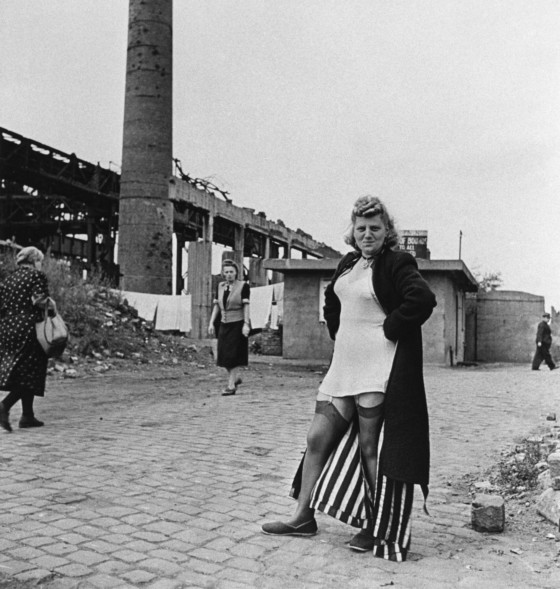

He was finally able to go back to photography in April 1947 when This Week magazine assigned him to photograph the places of the U.S. Army’s progress in Europe during the last months of the war. In his story We Went Back, he tracked down the still-fresh memories of war in impeccably composed Rolleiflex photographs, some in color. Upon his return, he found a telegram waiting for him in Paris. It was from Maria Eisner, the woman who was to become Magnum Photos’ first bureau chief: “You are President of Magnum Photos. Detailed letter sent to Paris on May 22nd. I will soon have interesting assignments for you. Advise you against coming back now. Wait for me in Paris.”2

Before the war, Seymour had often discussed with Capa, Cartier-Bresson and Rodger the idea of a photographic community, a cooperative to be run by and for photographers. “Without Chim,” Cartier-Bresson once told me “Magnum would not have existed, because he drew up our by-laws.”3 Seymour soon proved a formidable businessman and negotiator whose precise and methodical mind counter-balanced Capa’s enthusiasms. He was also great at public relations, and capable of blending into any milieu.

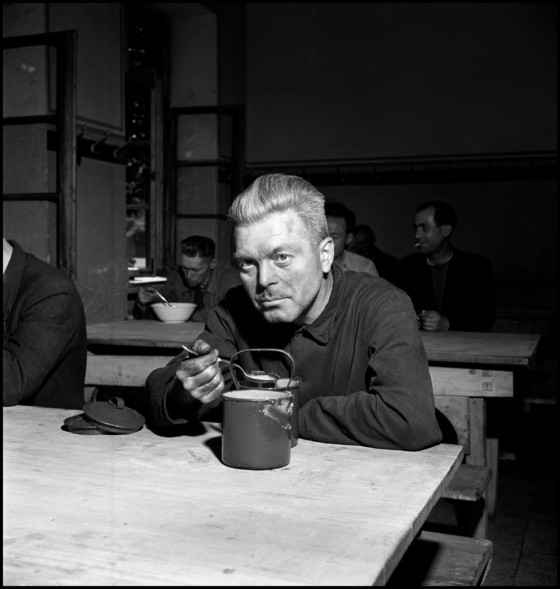

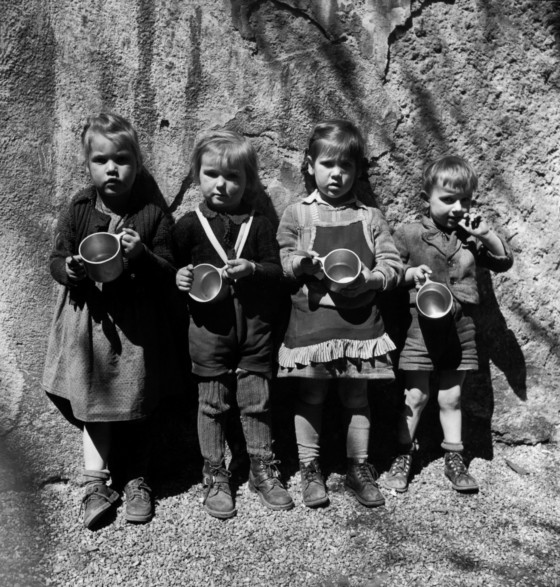

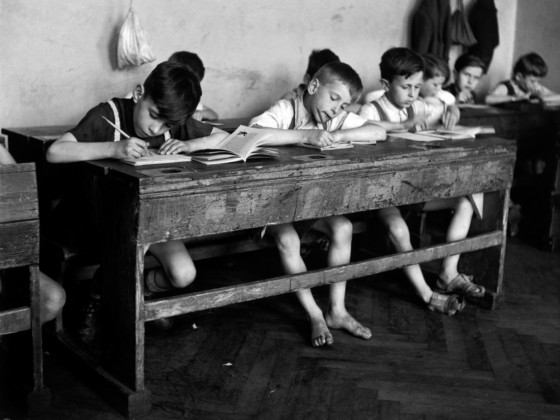

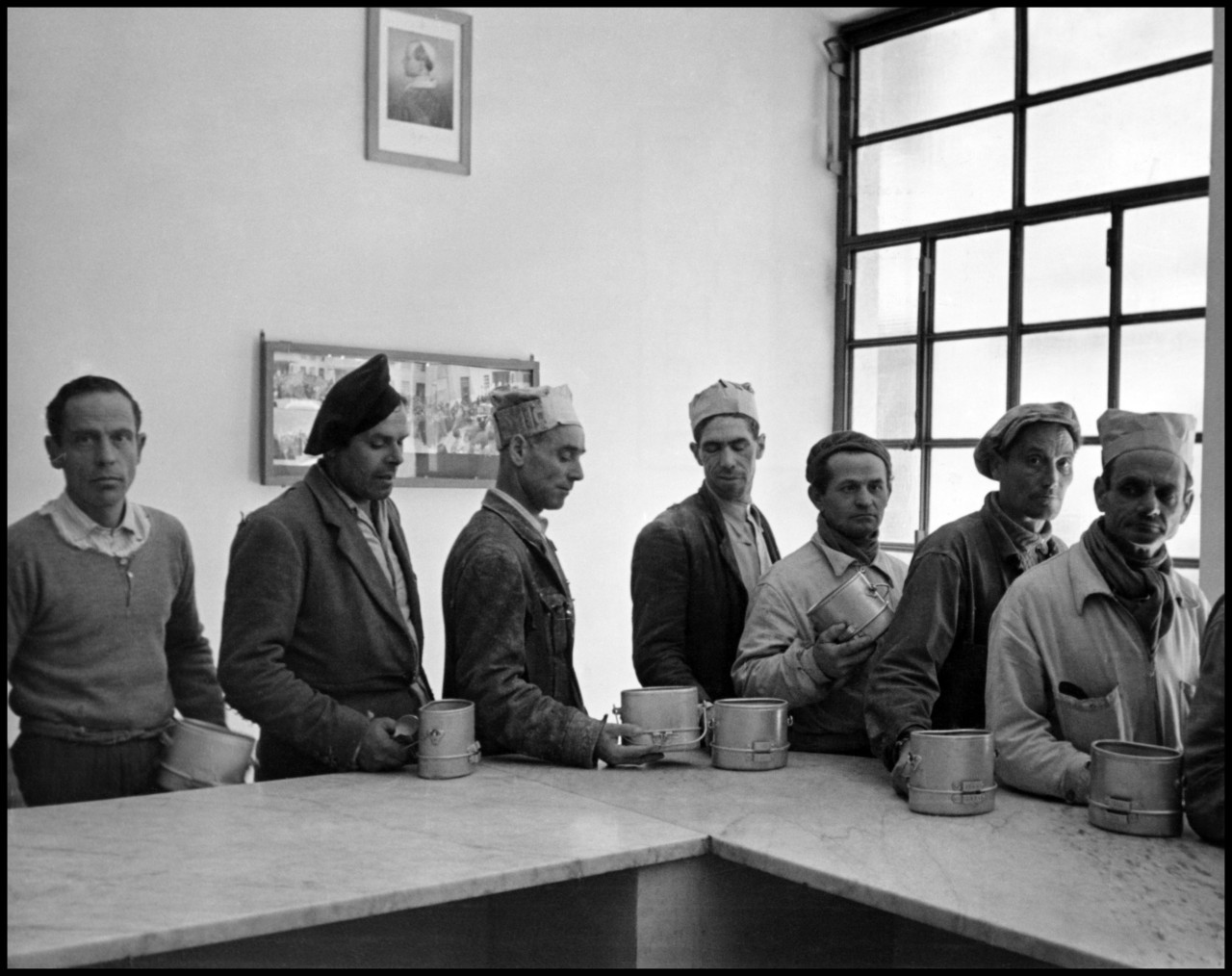

Designated a ‘special consultant’ by UNICEF in March 1948, Seymour embarked on an assignment to document the living conditions of the child survivors of World War II. The assignment would take him to five countries. One of his most famous images was made in Warsaw in a school for disturbed children. Tereska’s rendition on a blackboard of her ‘home’ is an inchoate scrawl, a reflection of her deep trauma. Seymour had recently learnt that his parents had been killed by the Nazis and projected his raw emotions into his Children of Europe series.

In 1949, he moved to Rome. For a book on the Vatican, he took some 2,500 photographs, from workers to a portrait of the pope made during a private audience. One of his most moving Italian stories, made with his friend writer Carlo Levi, was about illiteracy. One striking photograph focuses on the calloused, worn hands of an old peasant gripping a pen as he hesitantly traces the outlines of letters of the alphabet.

By 1951, Robert Capa was working as both a photographer and a ‘packager’ of stories. He came up with one on a large scale to be handled entirely by Magnum photographers: ‘Generation X’ was to be about children coming of age after the war. Seymour started in November with two subjects in Italy, who shared a desire to escape their environment. From 1951 to 1955, he documented the traditional religious festivals and processions held in Italian villages, and made a number of trips to Israel as the newborn state was fighting against attacks from neighboring Arab states. Israel became extremely important to him symbolically and emotionally, as the place of new hopes for the Jews of Europe.

1954 was a tragic year: on May 16, Werner Bischof died in an accident in Peru, and on May 25, Capa stepped on a landmine near Thai Bin. Seymour’s letter to Magnum summed up everyone’s feelings: “My Dear Magnum family, the lump is still in the throat, and the dust not settled yet. The blow is hard, and the reaction slow to come… We have to go on, keep together, and avoid the stunning effects of our sorrow. Maybe through this we will help ourselves, and find strength to keep and develop Magnum—a home for all of us.”4

George Rodger helped Seymour keep Magnum afloat. Cornell Capa, Robert’s younger brother, joined the agency and Seymour became president again. Magnum soon had twenty-four new members and associates. After the blow of Capa and Bischof’s deaths, it was a whole new generation. Seymour found his duties as president a heavy load, but by the end of October 1956, he was confident that he had put the situation to right.

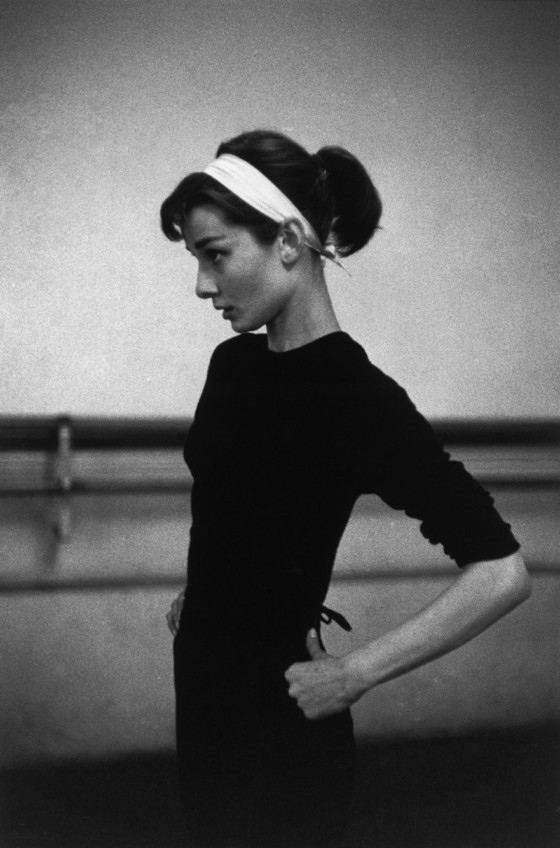

Magnum photographers capitalized on the coverage of movies for magazine publications and Seymour was soon selling portraits of Cinecittà stars to House and Garden, Holiday, Newsweek, Epoca, Harper’s Bazaar, Look, Paris Match… His unobtrusive manner and sense of humor, his ability to listen, helped in the creation of portraits that went beyond the usual “glamour shots,” conveying an air of relaxed intimacy. Among his subjects were Ingrid Bergman and her family, Audrey Hepburn, Joan Collins, Ava Gardner, Kim Novak, Kirk Douglas, Gina Lollobrigida, Rita Hayworth, Irene Papas, Maria Callas, Sophia Loren and many others. Seymour also produced portraits of writers and intellectuals like Arturo Toscanini and Bernard Berenson.

On October 14, 1956, Seymour was in Greece when he heard that Egypt had attacked Israel. He wrote Trudi Feliu: “It was clear to me as soon as I had heard the news that I was to return to some basic center of operations…. I would like to be into things… At first sight I feel we cannot stay out of world events if we are to grow as a group in world photography.”5

He arrived in Port Said on November 7 with journalists Frank White and Ben Bradley, and joined forces with a Paris Match photographer, Jean Roy. Frank White remembers that Seymour was fearless, taking more and more risks. That night, Bradlee and White left to file their stories. Bradlee delivered Seymour’s rolls of Port Said film to the Magnum Paris office.

They were to be his last films. On November 10, Seymour and Jean Roy took off to photograph an exchange of prisoners that was to take place at Al Qantara, the last post before the Egyptian lines. For unknown reasons, the two continued driving their Jeep at full speed and did not stop when Egyptian soldiers summoned them.

They were shot by Egyptian machine-gun. Three days after the cease-fire, David ‘Chim’ Seymour, forty-five years old, was dead, his creative life cut short.

End notes: 1 Letter to Emma, May 13, 1933, the David Seymour Archive, www.davidseymour.com. / 2 Telegram from Maria Eisner, May 22, 1947. The Magnum Archive, Paris. / 3 Interview with Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, January 14, 1998. / 4 Letter to Magnum, May 27, 1954. The Magnum Archive, New York. / 5 Letter to Trudi Feliu, October 31, 1956, John Morris Archive, University of Chicago.