Desire Lines: Reframing the American Road Trip Narrative in Alec Soth’s Photographs

In response to a series of maps in which the Magnum photographer traces his projects, Rebecca Bengal reflects on the psychology, history, and art of journeying in the United States

The following feature, by Rebecca Bengal, was originally published in Issue 30 of IMA Magazine, which can be ordered here. Reproduced here also are four maps which Alec Soth created for the issue, and to which Bengal refers in the text.

Magnum Learn’s second on-demand online course – Alec Soth: Photographic Storytelling – offers unique insight into Soth’s best-known projects and photobooks, as well as his practice and processes, through more than five hours of exclusive video content. Watch in-depth interviews, on-location shoots, and practical demonstrations; to learn more about the course, visit the link here. You can watch the course trailer at the bottom of this article.

You can purchase a number of Soth’s books, prints, and posters on the Magnum Shop, here.

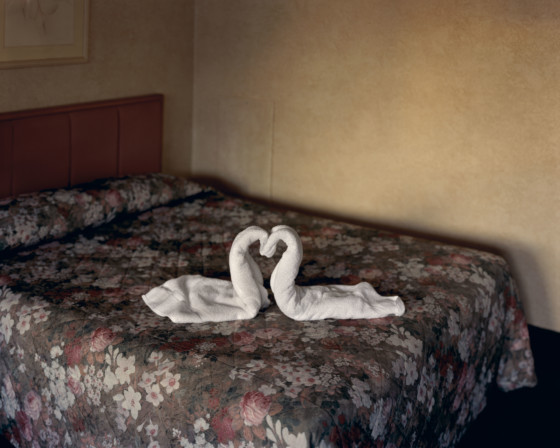

In 1954, when the Swiss photographer Robert Frank applied for his first Guggenheim fellowship, the things he planned to photograph, according to his proposal, included “a town at night, a parking lot, a supermarket, a highway, the man who owns three cars and the man who owns none.” Taped to Alec Soth’s steering wheel, when he drives out to photograph, are his own lists. For Niagara, his 2006 book of honeymooners and jilted lovers who loitered at the motels and bars on either side of the North American border of Niagara Falls, for instance, he set his sights by a smattering of quotes from Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita and an updated catalog of what that particular four-mile stretch of Canada-US roadside might deliver: “high-school yearbooks, Polaroids, men in pajamas.” You can read either list as an itinerary—or not, because a road trip is apt to veer off course, forming its own narrative.

"For Niagara, his 2006 book of honeymooners and jilted lovers who loitered at the motels and bars on either side of the North American border of Niagara Falls, [Soth] set his sights by a smattering of quotes from Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita"

-

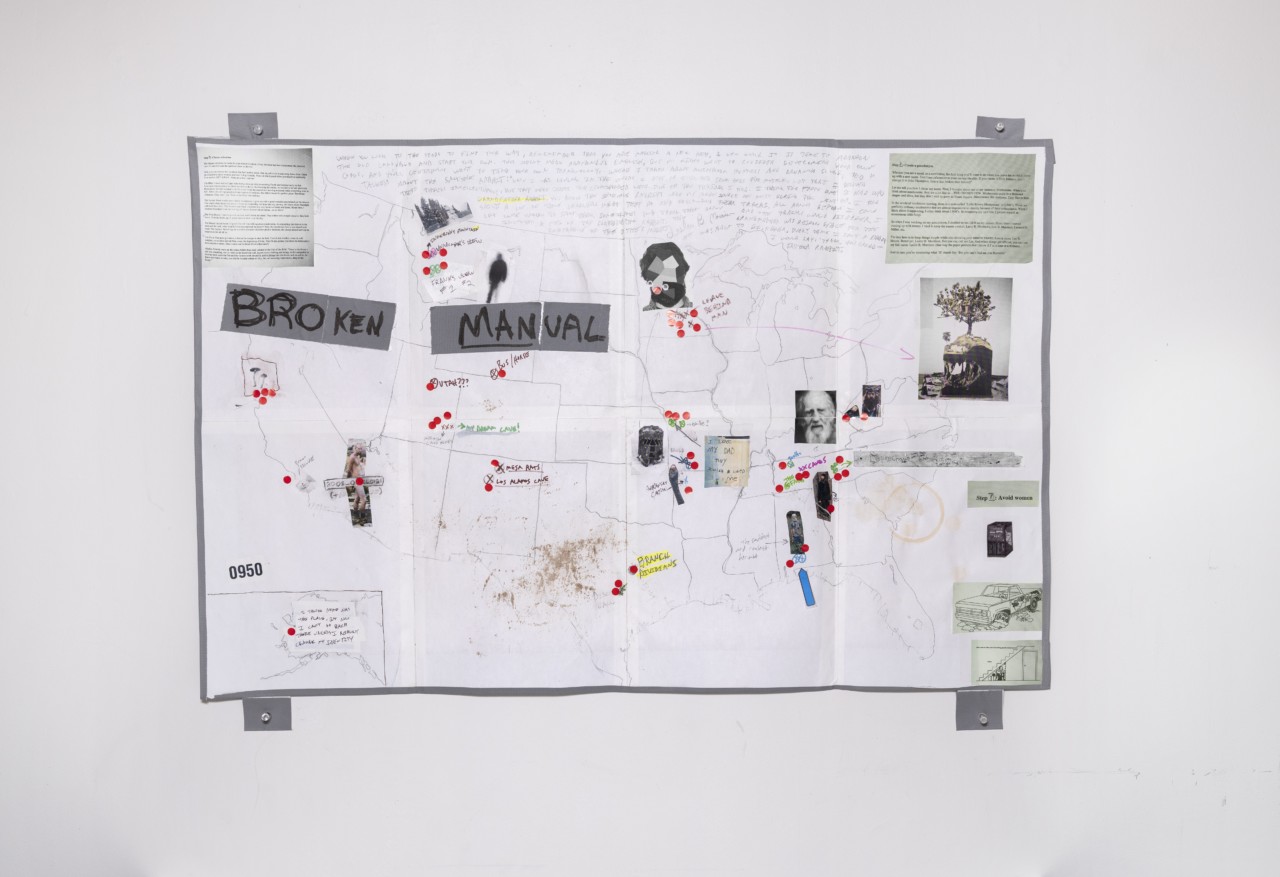

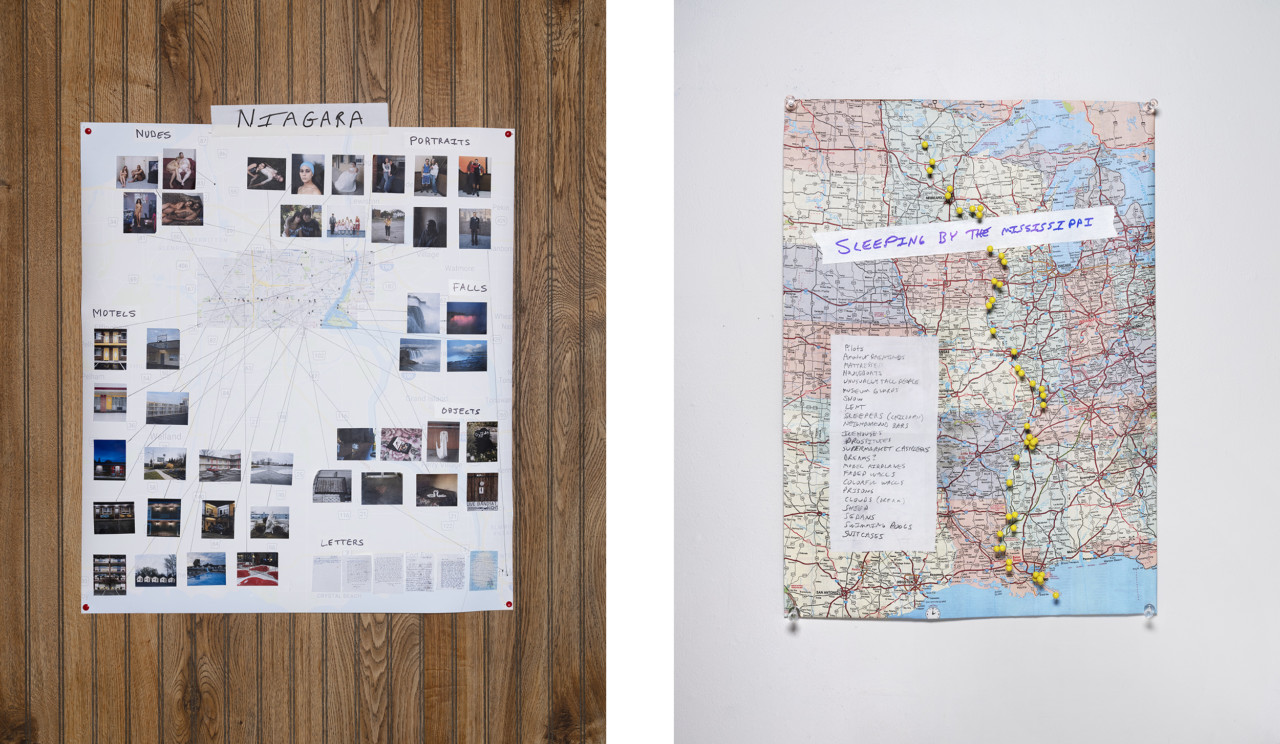

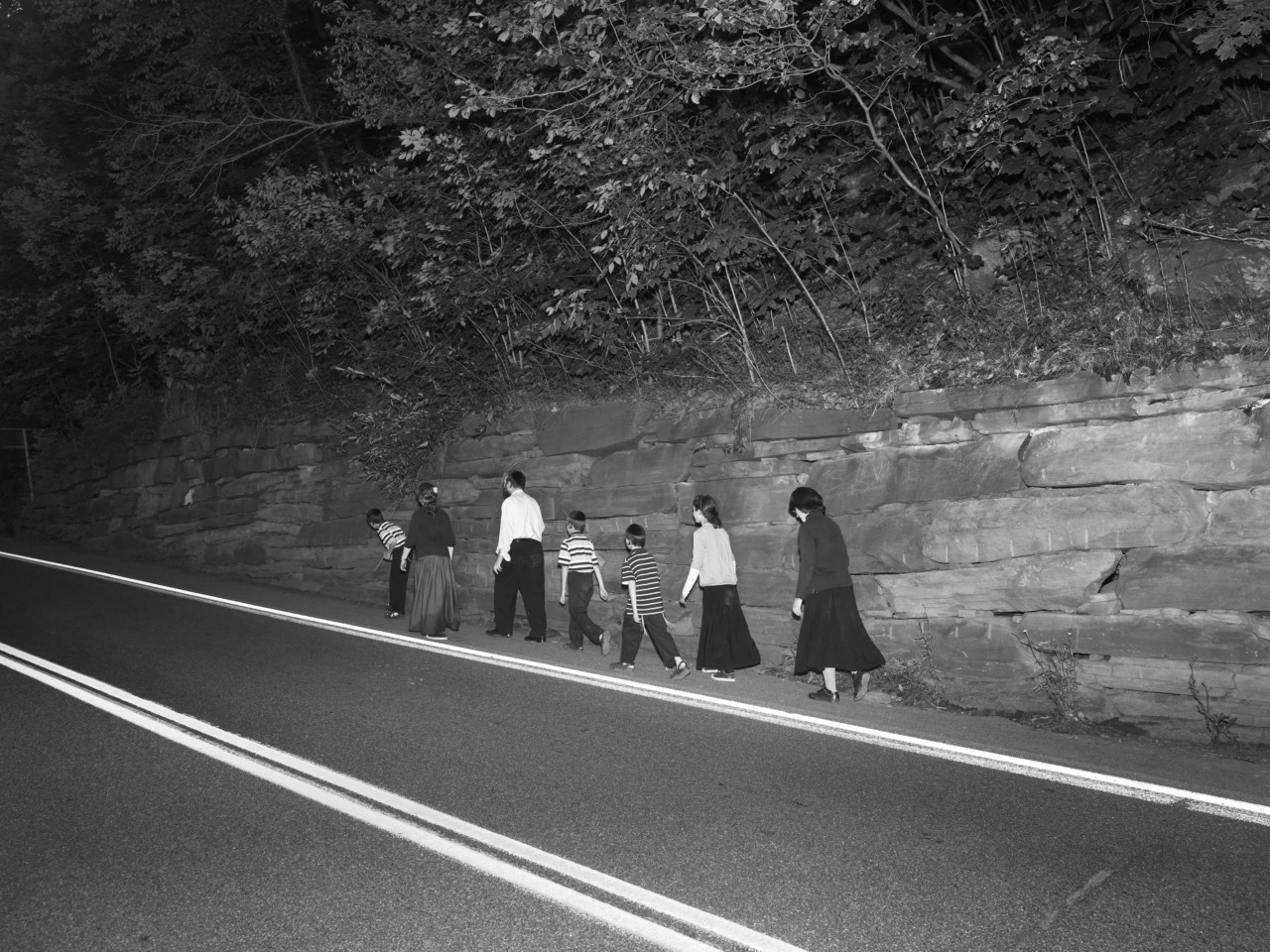

This is best seen in the maps Soth created recently, of the photographic road trips that resulted in four of his monographs. In fact, let’s veer off course for a moment and look at the very different shapes they make. Niagara roams the edges of its central motif, an inventory of letters, motels, nudes, objects, and of course, the falls themselves. The photographs in Songbook came out of the LBM Dispatch series of broadsheets Soth made through his publishing imprint Little Brown Mushroom with the writer Brad Zellar, in which they portrayed nebulous and mythic and ordinary regions as if they were local reporters or Sherwood Anderson writing Winesburg, Ohio. The texts were not used for the book, but its map nonetheless resembles a collection of newspapers fanning out from small, scattered towns.

Starkest is the difference between the fragmented structure of Broken Manual, a book of loners and hermits, hidden in random spots all over the United States, and Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004), whose map traces a jagged, curving line like a backbone down the middle of the country, from Minnesota, where Soth grew up and still lives, down South to Louisiana. It is a road that is a river that is also a metaphor in the American imagination.

“It’s surprising, because the line is so evenly dispersed,” Soth says. “It’s like the structure of a thriller; it all holds together and that’s not the way things usually work.” The first time Soth and I spoke several years ago, he’d called Sleeping by the Mississippi a “neurotic road trip” and also “a kind of country-western.” I knew that the making of the book was not so straightforward. I’d always liked the poetry of those steering wheel lists, for instance, but rarely, Soth said, would the items on them actually pan out. They were an excuse to make other discoveries, just as the presence of the river was an excuse to wander along it.

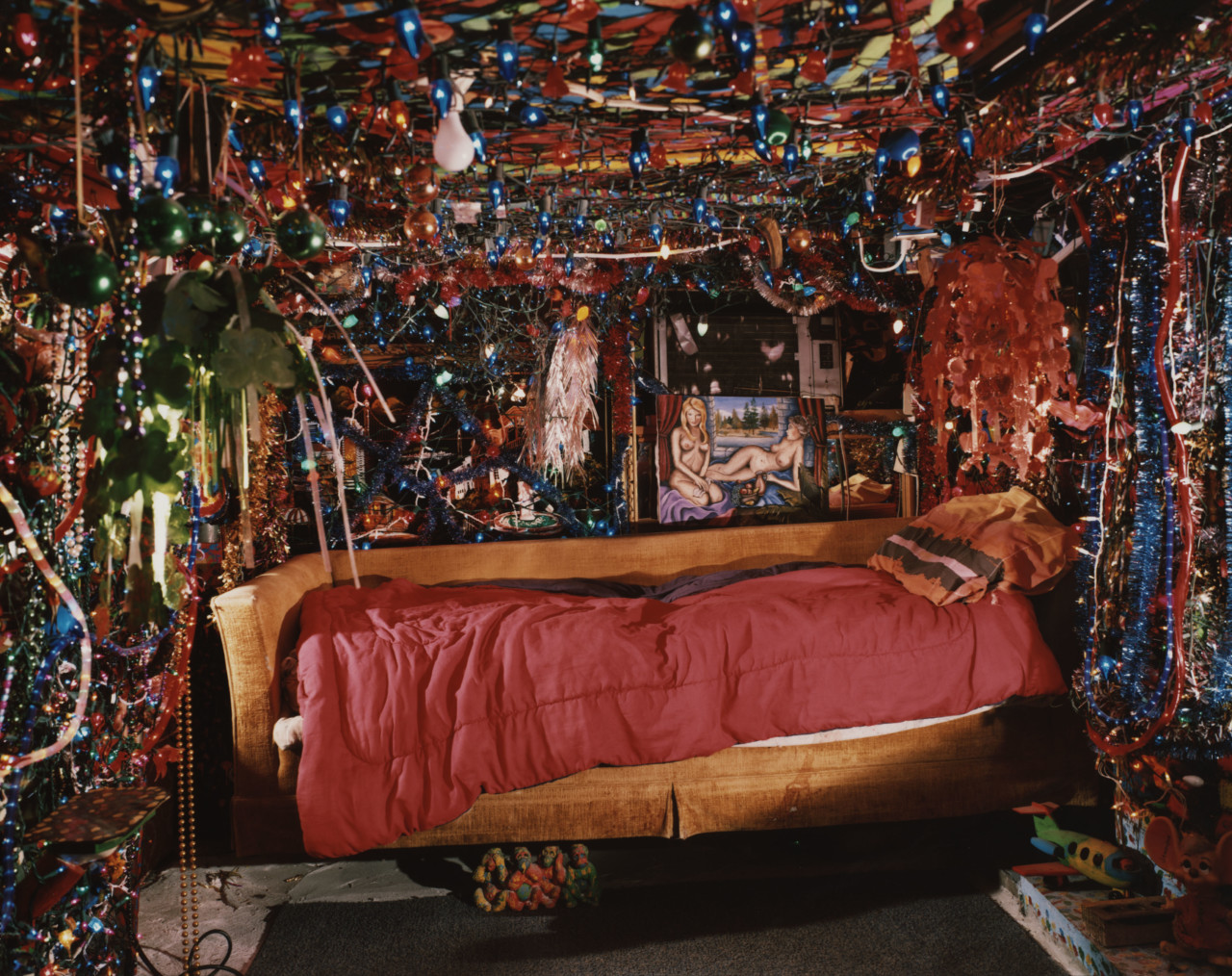

Sleeping by the Mississippi is a book about American dreamers, as its photographs of beds repeatedly remind us; the way we impress our private individualized longing upon our tiny worlds, how we project our desires onto our walls and out into our yards and onto the symbolic river. And to make Sleeping by the Mississippi, Soth roamed in a way that was also dreamlike, guided by instinct and whims and research he gathered on the fly, often from the Internet, traveling from place to seemingly disconnected place, the gaps between each setting slowly forming a plot.

"There are visible desire lines within Soth’s frames for instance—the trampled weeds around a bedframe sinking into the ground, the footfalls in a cemetery"

-

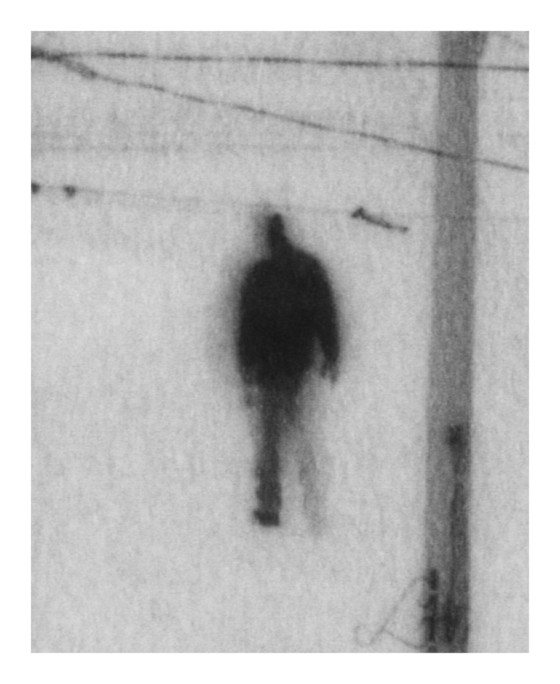

Recently I told him the maps of his books reminded me of desire lines, the phrase used to describe the phenomena of informal trails worn into the grass and snow by humans and animals. They are shortcuts sometimes, or they are secret paths, or they are escape routes, or they are simply the ways people and animals instinctively travel, veering off prescribe routes or walkways. Cows and elephants and other herding animals take desire lines to water; humans follow theirs at whim. There are visible desire lines within Soth’s frames for instance—the trampled weeds around a bedframe sinking into the ground, the footfalls in a cemetery. A work Soth frequently refers to is Richard Long’s A Line Made By Walking, a land art piece that Long created in a field near his home in Bristol, England by repeatedly pacing a continued line and photographing the flattened turf as it revealed itself, as visible as a chalk line in a sports field, or a divider on the highway. Essentially Long’s 1967 sculpture is a desire line too: performative and self-conscious. Whether they are meant to form impressions of the self, as Long did, or deviations from a planned course, desire lines are affirmations of the individual.

"Beneath the surfaces we travel are layers of the invisible past, embedded meanings that we don’t always visually perceive but which attract us on an implicit and subconscious level"

-

The urbanist Jane Jacobs and the architect Rem Koolhas were both advocates of planning cities in part by adhering to the desire lines already made clear. In Finland, some city planners wait for first snows to make evident the chosen paths and then chart walkways accordingly. In London, the landscape architect Riccardo Marini followed a trail of littered pieces of gum and cigarette butts to choose where to place city benches.

Desire lines run deep. In New York City, Broadway was plotted along a desire line walked by its first Native American inhabitants. It’s this aspect of desire lines that has long interested me, a writer of stories and a traveler, and which I had always suspected has long interested Soth. How, beneath the surfaces we travel are layers of the invisible past, embedded meanings that we don’t always visually perceive but which attract us on an implicit and subconscious level.

“It’s like Rebecca Solnit’s atlases,” Soth tells me. The author of Walking and A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Solnit has also published atlases of several American cities in which she maps the cultural history of a place. “In hers,” he says, “a map of a city might show you the location where, just to make up a hypothetical example, fruit is sold now but where there used to be prostitution.” This is also why it adds extra dimension to know that Soth’s photograph of a bed with old rumpled covers is the one where the famous pilot Charles Lindbergh slept and dreamed as a boy.

If desire lines are embedded in our roads, so is the idea of the road trip in photography. Let’s backtrack for a moment to its earliest days, at the start of the twentieth century. With the advent of the car in America came the road atlas and the camera. Beginning in 1906, the Rand McNally map company branched out beyond making highway atlases, introducing a series of photo-illustrated guidebooks of the United States made up of pictures taken from inside a car. They were essentially very early precursors of the Google Street View vans that prowl the globe today, documenting every street banality and detail. Virtually transporting the reader to unfamiliar parts of the country, they effectively established the concept of the American road photobook as guide, an idea that has bled into the worlds of art and documentary, and persists today.

In 1938 Walker Evans became the first photographer to receive a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which was accompanied by a book of the same name, American Photographs. Though neither a guidebook nor the chronicle of a road trip (the images were made over the course of a decade), the pointed title Evans chose, coupled with his perfectionist and unsentimental style and subject matter made the pictures feel declarative, definitive, and emblematic. Of course there was a real person behind the camera, seeing and making choices, but Evans did his best to make viewers of the pictures forget he was there.

In 1955, when Frank published The Americans, the American fervor for the road was at a high. The US was manufacturing three-quarters of the world’s cars, inciting an artistic fascination with the automobile. In 1947 Frank’s friend Jack Kerouac wrote the first draft of his wanderlust Beat novel On the Road, famously typed on a continuous paper scroll (though the book was heavily edited before its publication). In 1953, to make his work Automobile Tire Print, Robert Rauschenberg pasted twenty sheets of typing paper together, laid them out on then-deserted Fulton Street in New York City, and invited his friend John Cage to come over with his Model A car. Rauschenberg poured black paint onto Cage’s tires and instructed him to drive slowly and as straight as possible. The continuous tire print that resulted prefigures Long’s A Line Made By Walking. It resembles a tire track on a road; it resembles the fantasy of the highway itself; it resembles the wild speed-fueled rush of Kerouac’s seemingly endless script. It is the classic American story of the road. “There’s something corny about it,” Soth says of road trip photography. “I’m embarrassed of using that structure. But I keep returning to it.”

Soth came to Frank secondhand, via the generation of American photographers who the Swiss-born photographer had influenced, and especially through the books they made, from their own American road trips. “I wasn’t overwhelmingly influenced by Robert Frank starting out,” Soth says. “I was sorting out who I was as a photographer.” Their titles either bore the gravity of their subject matter—Joel Sternfeld’s American Prospects, Stephen Shore’s Uncommon Places and American Surfaces—or pointedly addressed it, as William Eggleston did with Los Alamos, using the name of the town where the atomic bomb was invented to represent all of America. Eggleston is the title king, Soth says, whether with the evocative The Democratic Forest or, in William Eggleston’s Guide, slyly twisting the notion of photobook as travelogue, acknowledging the artist as guide.

"It’s like Rauschenberg and Cage’s straight line, it’s Kerouac’s unbroken typescript, it’s the distinct pictures considered as a narrative whole, the isolated individuals in them forming a collective story"

-

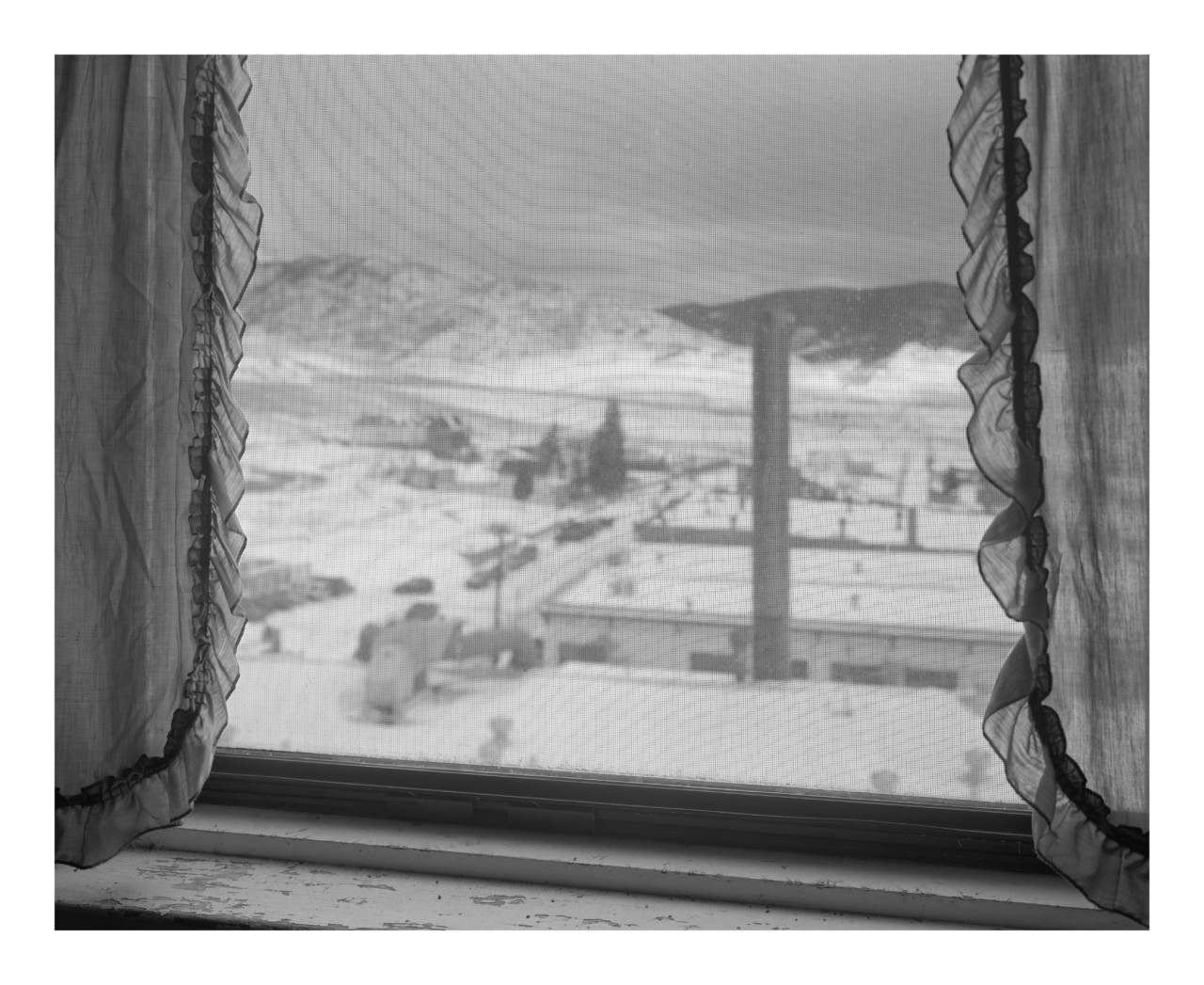

Eventually Soth came to find an affinity with Frank’s deceptively outward-seeking, essentially inward-looking pictures—the ones Frank’s friend Kerouac said “sucked a sad poem right out of America.” “In retrospect The Americans is a lot about Robert Frank,” Soth says. “You see that [in “View from Hotel Window, Butte County, Montana, 1956”] the real awareness of the author standing there at that window. It’s as much a picture of Robert Frank standing at the window as it is a picture of what’s outside of it.” Framed by gauzy curtains, Frank’s window opens out onto the smokestacks of a lonely-looking mining town, and onto the mountains in the horizon—a portrait of self, of reality outside, of a more distant, westward dream, all at once. On the road in Montana while making Broken Manual, Soth created his own version of Frank’s hotel window photograph.

The presence of the photographer is palpable in the final picture of The Americans too, a photograph of Frank’s first wife, the artist Mary Frank, and their children, wearily accompanying him on the road. The presence of Eggleston is perhaps most evident in the pictures he made closest to home in Memphis and Mississippi. And the formalist photographer Shore briefly but significantly acknowledges the self too, via the tabletop photographs of his pancake meals; or the photograph of his wife, Ginger, included in Uncommon Places. “But I really feel the photographer’s presence in Frank’s hotel window,” Soth says. “Frank doing that is showing himself like the author sort of being the narrator.” In other words, he means, the artist-author as guide, pulled along by desire lines. “The road trip and the road itself become this thing you hang all the pictures on, the way you writers hang words on a narrative structure.” It’s like Rauschenberg and Cage’s straight line, it’s Kerouac’s unbroken typescript, it’s the distinct pictures considered as a narrative whole, the isolated individuals in them forming a collective story.

Sometimes it can be hard to determine from which direction the lines are originating. In his poem “On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist, and His Work,” John Cage lightly downplays what was possibly the shortest road trip in the history of artistic American road trips: “I know he put the paint on the tires. And he unrolled the paper on the city street. But which one of us drove the car?”