Documenting Style and Subcultures

An exploration of how societies are shaped by their subcultures, with a curation of images from the Magnum archive by Ekow Eshun

Magnum Photographers

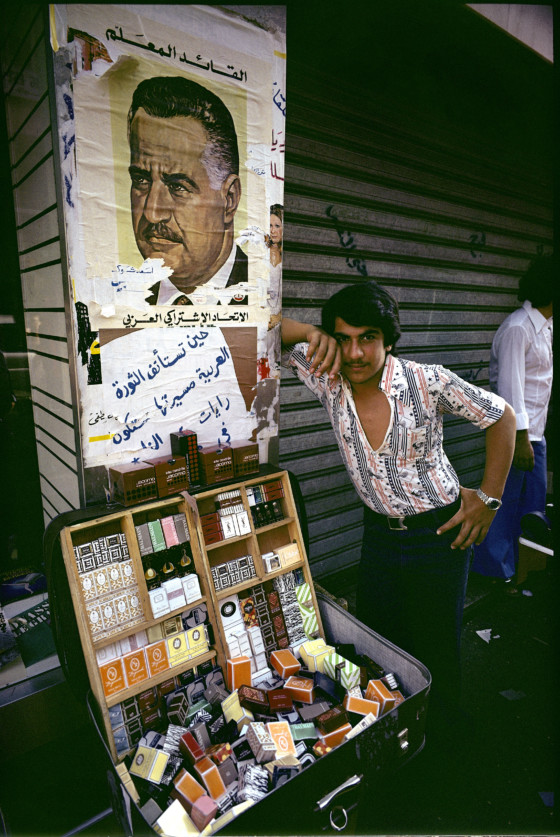

Subcultures have long offered a means for those living in the margins of society to seek out acceptance and respect among likeminded people. They become a kind of valve through which a community’s interpersonal pressures are released, manifesting themselves in subversive style, or music, or beliefs – distinctive behaviours which, over time, trickle into the mainstream via popular consciousness. The factors which cause these sub-sections to form in the first place, however, and the ways in which they are recorded, are incredibly diverse.

Some weeks back Magnum hosted a panel discussion at London’s Barbican Centre at which three key speakers – the curator of photography at the Museum of London, Anna Sparham, photographer Chris Steele-Perkins, and writer, editor and cultural commentator Ekow Eshun – presented their own reflections on the resonance of style subcultures. “These things are all around us,” Eshun explained, in a reference to Dick Hebdige’s seminal 1988 book Hiding in the Light, in which the author explores the creation and consumption of objects and images. “You walk down the street and you start to see how society interacts through the things that people wear, through how they talk to each other, through the music they listen to.” Here, we consider some of the ways that photography can be used to document subcultures, and what the practice of exploring these worlds through photographing them can reveal.

The Photobook as Historical Record

Subcultures offer an opportunity for the disenchanted and the discarded to become part of something greater than themselves – and by documenting such communities, photographers create windows into highly complex moments that future generations to learn from. As curator of photography at the museum of London, Anna Sparham has long-been preoccupied by the liminal space that exists between youth, fashion and identity; she cites Bruce Davidson, Robert Capa, Eve Arnold and Martin Parr as just a few pioneers in the documentation of style tribes. Nowadays, however, it falls to both print and online media to establish the contexts for shifts in style – and with this shift, Sparham, Steele-Perkins and Eshun agree that photobooks have become the most powerful means of demarcating such moments in cultural history.

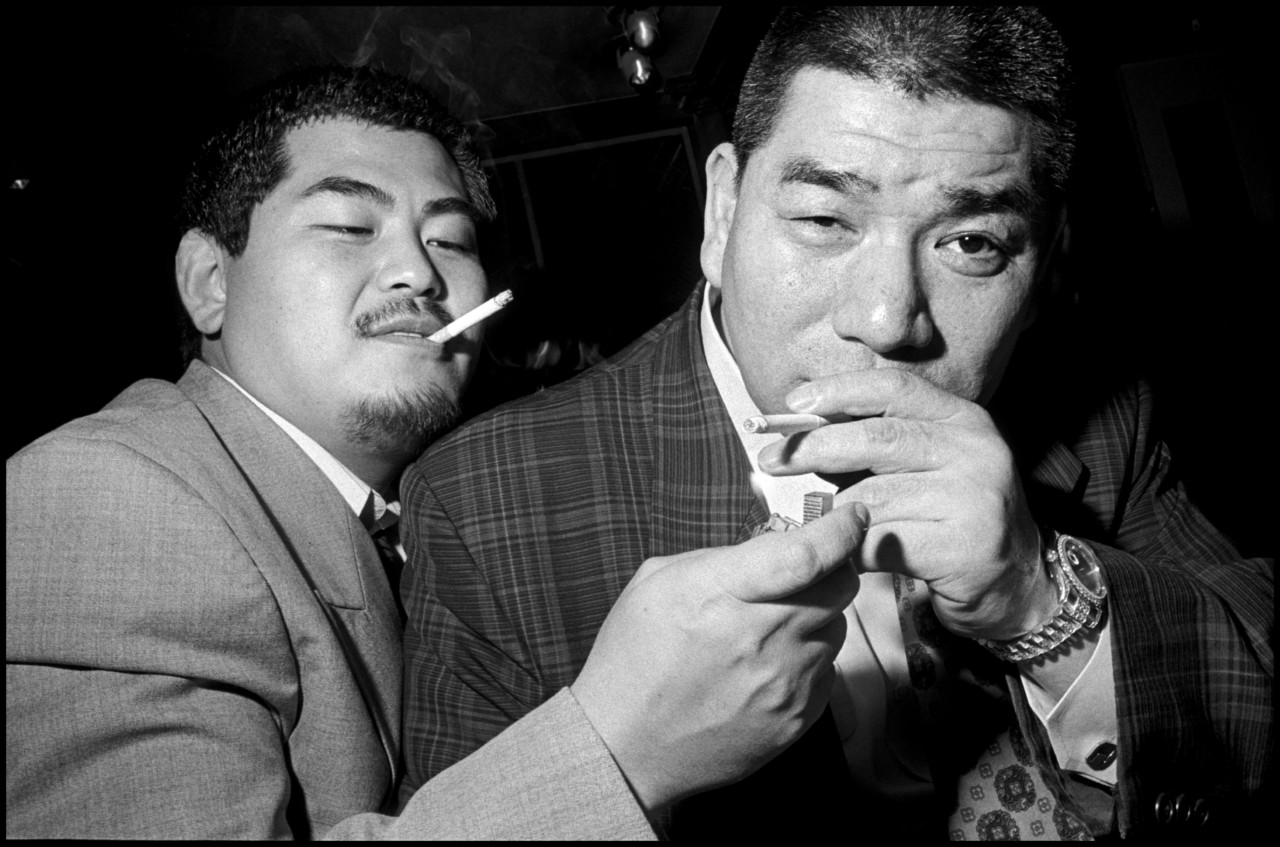

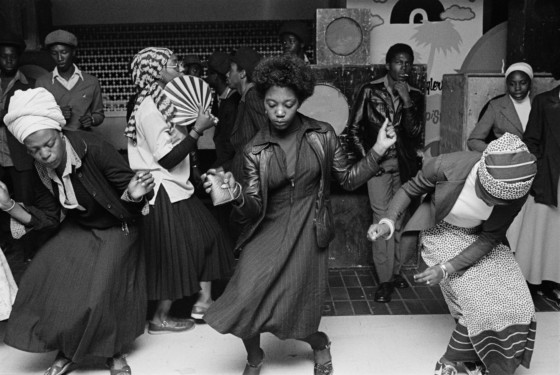

Substance Disguised in Superficiality

On first glance, considering black masculinity through the prism of style might be considered “a potentially superficial way of addressing some quite serious issues,” Eshun explained, describing the combination of factors which drew him to curate Made You Look: Dandyism and Black Masculinity at The Photographers’ Gallery earlier this summer. Where the person in question occupies a highly vulnerable position in society, however, he pointed out that transgressive style often gestures towards something much more resonant. “I tend to think that the way that any of us carry ourselves, the way we dress and comport ourselves, is powerfully indicative of who we are,” he said. “And when it comes to black men in particular, I think we see that in pointed detail, because these issues around visibility become quite heightened.” He used a photograph of a young black man London in the late 20th century as an example; he is dressed flamboyantly in skintight tartan trousers, a towering hat, and his shirt shrugged from his shoulders to reveal his bare chest. “Here you see someone behaving transgressively, in terms of style, but he has no status,” Eshun explains. “Therefore his choice to dress this way becomes all the more loaded – and all the more fabulous.”

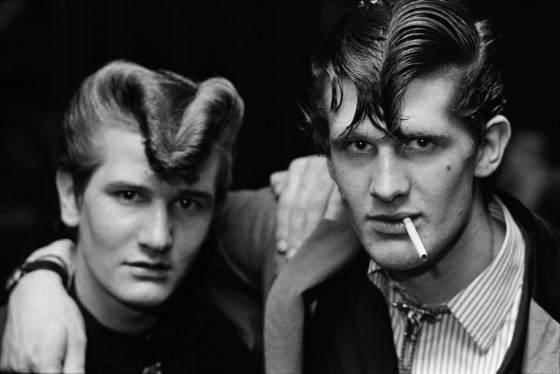

A Route to Understanding Society

When Chris Steele-Perkins first set out to photograph the resurgence of Teddy Boys in the 1970s, he was drawn by their singular style and defiant attitude. The more time he came to spend with his subjects, however, the more he came to realize that their search for allegiance was rooted in their rejection from established social groups. “These were working class kids who were going to be butchers and bakers and so on, and they wanted to be taken more seriously,” he explained. “They wanted people to pay attention to them – kids have always wanted that.” Their means of winning respect came through sartorial signatures discarded by the upper classes, he continued, from elaborate ruff collars to the traditional ‘drape’ overcoat. “It came from austerity, it came from charity shops,” he continues, “blended with what they could see about America in the newspapers and magazines. The Teds did it first, and they then became sampled by later generations, who were looking back to see what had come before.”

Read about more discussions from the Magnum Photos Now events here.