Empathy and Photography

Discussing the role of emotional connection as both an objective and a tool in documentary photography

Magnum Photographers

The power of photography to provoke emotions can be experienced as a visceral reaction that comes as a response to particularly heat-wrenching or exhilarating images, but empathy and connection also come into play in subtler ways. It might manifest in response to the image itself: for example, candid vignettes of refugees’ daily lives can help humanize them to an audience; or empathy might be present in the connection between photographer and their subject, enabling an intimacy that facilitates the making of resonating images.

The role of empathy in documentary photography was discussed at a Magnum Now Barbican event by speakers, Magnum photographer Olivia Arthur, Save the Children’s director of creative content Jess Crombie, and writer and photographer Colin Pantall. Here, we present some contemporary thinking on empathy and photography explored at the event.

A need for connection

Why might documentary photography need to provoke empathy, and how might this be achieved?

“My job at Save The Children is essentially to persuade people to give money and take actions that will help Save The Children do what we do in the 120 countries in which we work,” said Jess Crombie. “And the way that my team and I do that is to create empathy, and the way that you do that is by telling stories.”

The modern paradox

Why more stories doesn’t mean more empathy.

“In the old world, stories were transmitted from one to many, and we the one (the storytellers), told the stories to the many, and we curated what stories everyone heard. We were in control and people largely accepted them. In today’s world, stories go from many to many; many create, many curate, and there are many stories, so we understand how stories are told more deeply. We are storytellers and we don’t accept stories as easily. I felt that, surely, because everyone has a voice and a platform, everyone can understand each other; that because there are many more stories, they can create a world of better empathy, but this does not seem to be the case.” – Jess Crombie.

The real and the represented

How a lifetime of seeing highly edited stories might make it harder to empathize.

“We live in a world where what I’m calling the real and the represented are at odds with each other. In the old world, there was only the represented because only a few saw the real. Today, loads of us see the real and we tell stories about it ourselves, but because we spent most of our lives seeing the represented, when we see the real it doesn’t work for us.” – Jess Crombie.

Honesty in Mundanity

One suggested solution for achieving empathy through photography is to forgo highly edited and curated images in favour of the slower, more honest approach of showing the real in all its complexities and mundanities. One initiative that did just that was a Save The Children project that gave an Instagram account to Syrian refugee children in Jordan’s Zaatari camp (a camp also photographed by Magnum’s Mark Power), allowing them to post their day-to-day life, experiences, interests and friends.

Although Crombie admits that this way of working is still fraught with complexities and inadequacies, the real solution lies somewhere in the deliberate facilitation of this type barrier breaking down. “We didn’t edit the pictures, they did,” she said. “And so what’s so brilliant about that is you get this window into their world in a way that you don’t often get from what NGOs put out. It takes a bit longer to get to know those children, but in the end you get the same result – if you ask the if you want to help those children they say ‘yes’.”

“It’s about breaking through those preconceptions because I think we think we’re more sophisticated than we are,” adds Colin Pantall. “Our snap judgements are really quick and they’re basic.”

Rapport and Collaboration

For Magnum photographer Olivia Arthur, empathy comes into play between herself and her subject, rather than being something she is necessarily thinking about in terms of a future audience reaction. For a work-in-progress, photographing transgender people, Arthur’s approach is to sit with the subject for some time, listening to their story, building a rapport and then taking their portrait. “There’s a kind of formality to the way that I make the picture, but I think there is also an intimacy because she shared her story first, and the way that she trusted me with her story becomes very important in the way that she looks at me, in the way that she shares herself with the camera,” says Arthur, reflecting on the portrait she took of one woman.

“The person you’re photographing knows what kind of picture you’re taking of them as well, and there’s an honesty with that. I find it very rewarding to photograph people in this way. As a documentary photographer, you are always looking for that thing, that gesture, you’re always looking for something that’s not the obvious thing, whereas here you’re being very honest with people and you’re saying ‘I’m going to make this picture of you’, and you almost make it together.”

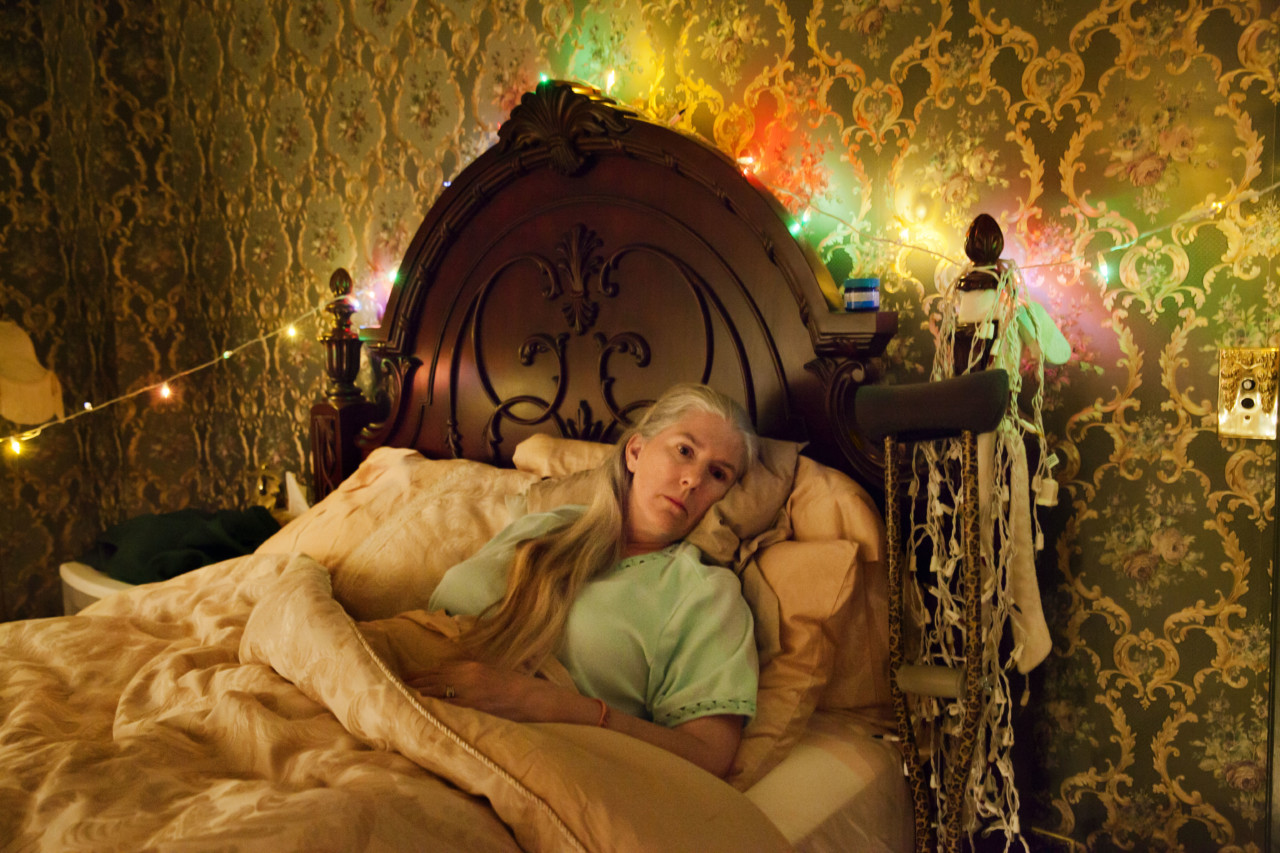

This is a similar approach taken by other Magnum photographers, including Bieke Depoorter, who not only talks with her subjects, but goes into their homes, shares meals, and spends a night – the resulting portraits offer unprecedented access into the subjects’ private lives and captures something of the genuine intimacy they shared.

Intimacy

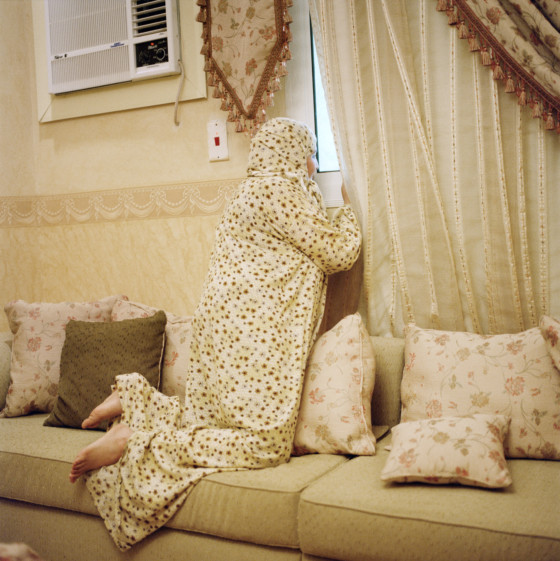

“I think, most importantly, my work is about intimacy, its about looking for an intimacy with my subjects,” says Olivia Arthur, for whom emotional connection with her subjects is a vital tool. “It’s not about my own personal intimacy, but finding a way into other people’s world, and finding a way for them to share their intimacy with me. It really is as much about them wanting to share that as it is me looking for it,” she says, reflecting on her work in Asia, exploring the lives of women, most notably those in Saudi Arabia, which became the subject of her book Jeddah Diary. “It is about looking for women who could have been me. It was a journey along the border with Asia, looking at influences of different cultures on people’s lives, but as much as anything, it was about looking for connections.”

Camera model and intimacy

Achieving intimacy with her subjects hinges on the way Arthur is viewed by them, and the type of camera she uses seems to have a profound effect. “When I went back on my second trip, I took a little digital, snappy camera with me, and it was really interesting because it opened up a way of taking pictures. Previously, I had been working with the Hasselblad, which is a big camera. It looks professional and it’s a slow process, and they know that I’m taking a picture. But then I used a camera like the sort of camera that they would use to take pictures of each other and they would forget that I am the professional photographer.”

“I started to take these pictures that were much more informal, they were much more intimate and represented a slightly different role that I had there – they saw me as a friend, we could hang out together, take pictures, put on their make-up and pose. It was a different sort of atmosphere.”

Read about more discussions from the Magnum Photos Now events here.