Finding Your Documentary Photography Style

Two young Magnum photographers on how they developed their own style of documentary photography

Magnum Photographers

Aside from mastering the basic technical skills, the biggest challenge an aspiring documentary photographer faces when starting out in the practice is forging a style of their own. One common mistake is to rely too heavily on the work of more established photographers for inspiration. “Keep true to yourself,” was the most memorable piece of advice given to Bieke Depoorter, who became a full Magnum member in 2016, from the older, more established Magnum members.

Speaking at a Magnum Photos Now event at the Barbican in London, Bieke Depoorter, and Magnum nominee Max Pinckers discussed how they had both developed their different documentary styles. One approach was borne out of theory, while the other manifested from the photographer’s personal feelings and emotions.

A Theoretical Approach

Max Pinckers developed his documentary photography style whilst studying at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent, Belgium, where his thinking began to develop around questions of authenticity. “I’ve always been questioning, as a maker or as a photographer, the relationship with the subject matter and the images produced, and how far can they actually convey a form of truth,” he said.

“Can you take a picture of something, or someone, or an event and bring it back home and expect people to understand what you photographed? This led me to try to make a documentary about something you can’t actually see, which you can’t point your camera at and press the button, because, if I was able to do that, I would be able to photograph a thought or an idea or a concept – something that is in the air.”

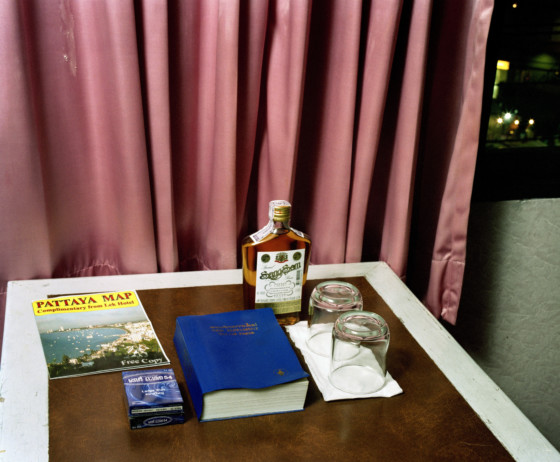

Working in collaboration with visual artist Quinten De Bruyn, Pinckers travelled to Thailand to document the famous transgender community there. Having grown up in Southeast Asia, he was familiar with this part of the world. As a student of photography, he wanted to use the setting as not only a subject matter, but a vehicle to explore the very medium of photojournalism itself.

“What we were really interested in was the kind of thought behind why certain aesthetics are applied in documentary photography or photojournalism. What are the motivations behind making certain aesthetic choices when you’re actually there to report on a certain subject matter? Why do documentary images need to be pretty or beautiful or nice to look at? Even if the subject matter might be completely in conflict with this aesthetic? We chose Thailand’s Ladyboys because they have also gone through some kind of transformation; they have plastic surgery and turn from looking like a man to looking like a woman. You walk through the streets and sometimes you’re not quite sure if you are looking at a man or a woman. This is interesting because that’s exactly what we wanted to convey with our images as well: the viewer questions the authenticity of what they are looking at.”

"What are the motivations behind making certain aesthetic choices when you’re actually there to report on a certain subject matter?"

- Max Pinckers

Working together, the pair came up with a workflow, whereby one of them would set up the lighting while the other would shift furniture in order to create a good composition, creating a very controlled photographic environment for theatrical lighting. Then, they would wait for people to get used to the set-up and become more relaxed. “All of a sudden, they started chatting to each other or would get up to go to the bathroom and then we would take the picture right at the moment when something spontaneous happened. We wanted to to achieve this very stylized, theatrical photographic aesthetic but at the same time capture something that we might not be able to direct or stage.”

This led to another project that also captured not only a physical subject but asked questions about photographic theory and authenticity. Pinckers wanted to document the way Bollywood film is so ubiquitous in Indian culture. “Of course you can do this by taking posters of Bollywood movies or maybe go to film sets and take some pictures of actors or directors and try and explain that this is a very important part of the society,” he said, but “your images aren’t telling it on their own.” Instead, the photographer began to set up equipment in the streets of Bombay and asked people in the street to be his “actors” – they instantly knew what to do. “The fact that these people just willingly jumped in front of my camera and pretended to act shows exactly how powerful this cinema fantasy is for them. That’s another strategy that I developed in order to achieve what I was trying to say, but it’s still a documentary for me.”

Feeling your way

Magnum member Bieke Depoorter, who also studied photography the Royal Academy in Ghent, developed her documentary style in an almost opposite way to Pinckers. Rather than starting with photographic theory, Depoorter’s documentary approach developed intuitively. Having grown up not being exposed to much art or photography – Depoorter’s first visit to a museum happened while she was at photography school – she had very little in terms of a visual references to work from, so Depoorter found her way based on what felt right for her.

In 2009 Bieke Depoorter travelled through Russia, photographing people in whose homes she had spent a single night, for her graduating project Ou Menya, which won several prizes, including the Magnum Expression Award, and led to a book, published by Lannoo in 2011.

“I wanted to travel on the trans-Siberian train and stop in small villages and photograph there,” said Depoorter, speaking at the Magnum Photos Now event. “I didn’t have money for hotels and in the places that I wanted to visit there were often no hotels, so I asked the first girl that I met in Moscow who spoke English to write me a letter that said ‘I’m looking for a place to sleep’ so that I could find a place at night. The first night, I ended up in small village and it was getting dark so I showed the letter to people to find a place and some people took me in. It was an eye-opener because I took pictures and finally I felt comfortable with photography.”

" It was an eye-opener because I took pictures and finally I felt comfortable with photography"

- Bieke Depoorter

Previous to this point, Depoorter struggled to find her niche, and tried her hand at street photography, which she never felt truly comfortable with. “I was always trying to be a street photographer but I felt like I was stealing people’s pictures, in a way. When I was staying the night people really opened up for a few hours and I could take pictures of very intimate moments. I thought that maybe I should do it every night and focus on the intimacy of families and see what happens during my trips.”

While she may not have found her feet as a street photographer, following her intuition led Bieke Depoorter to cultivate her forte in creating exceptionally intimate portraits. The photographer also developed her particular passion for the twilight hours; spending the evening with her host, she’d usually have found a comfortable intimacy by bedtime and often took portraits of her subjects as they got ready to go to sleep.

“The moment before people go to sleep is very intense and that’s something that I like to capture. I think outside we sometimes pretend to be someone else or someone we want to be and once you are home I have the feeling that people are more real, they don’t pretend anymore. The moment that we go to sleep is really a moment for yourself and you’re in your own thoughts and your own mind and that’s something that I really like to be with and to capture.”

Read about more discussions from the Magnum Photos Now events here.