Finding Your Subject

Five very different ways Magnum photographers have found inspiration - and can help you find yours

No two Magnum photographers are the same, and what they decide to point their lens at is motived by a myriad of factors. Second to a drive to pick up a camera, comes the inspiration that grips the photographer, sometimes holding their attention for decades, or an entire career. How a photographer finds their subject comes about in as varied ways as there are styles in which to photograph. And for many aspiring photographers, finding that spark of inspiration can be the most difficult hurdle in their development.

Here, we present five very different ways that Magnum photographers have found a subject they’ve been inspired to photograph, which has formed the basis of seminal work or has helped to define their signature approach. For readers in search of inspiration for their next project, or more profound guidance on where to take their practice, these stories offer some suggestions.

The political climate

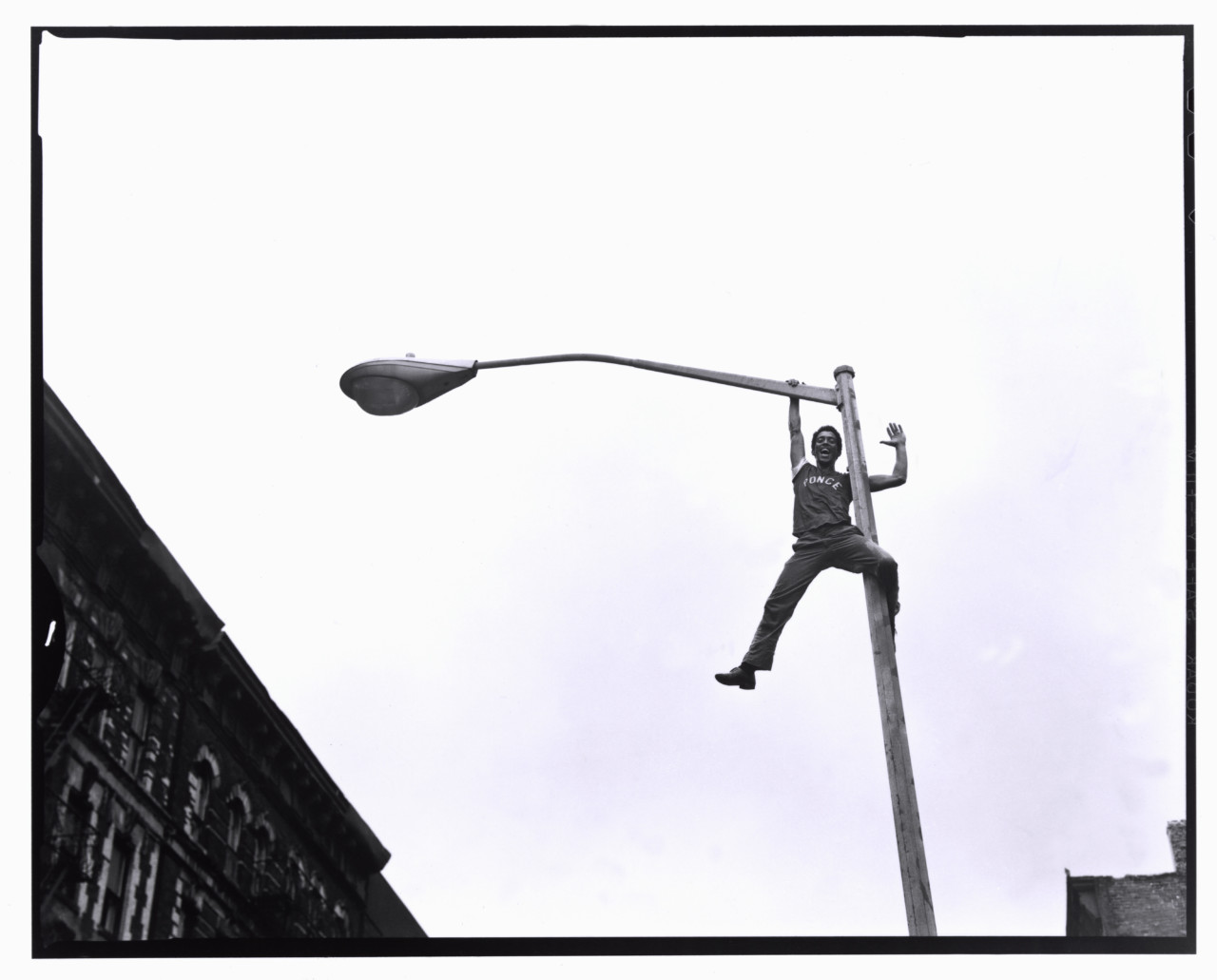

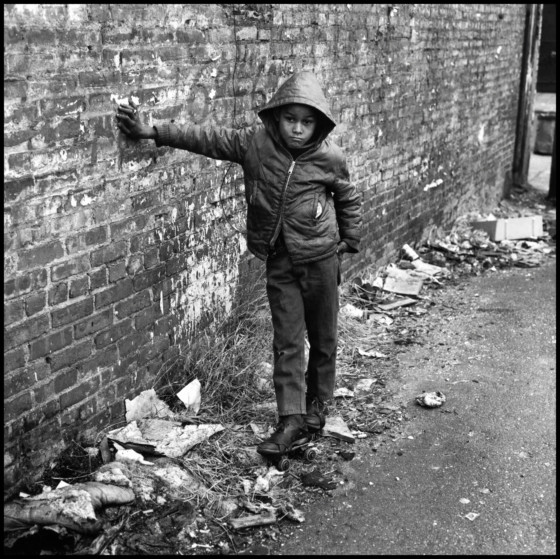

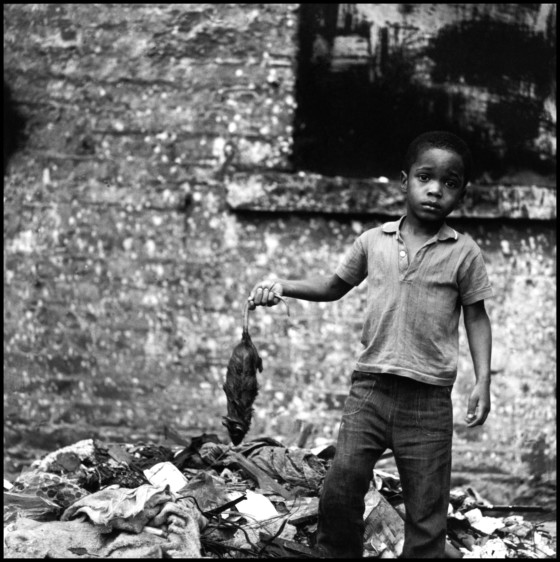

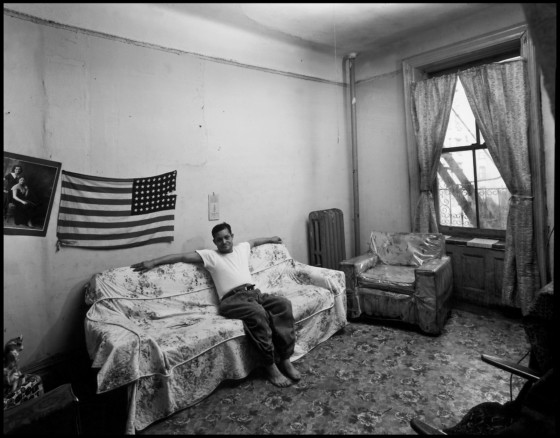

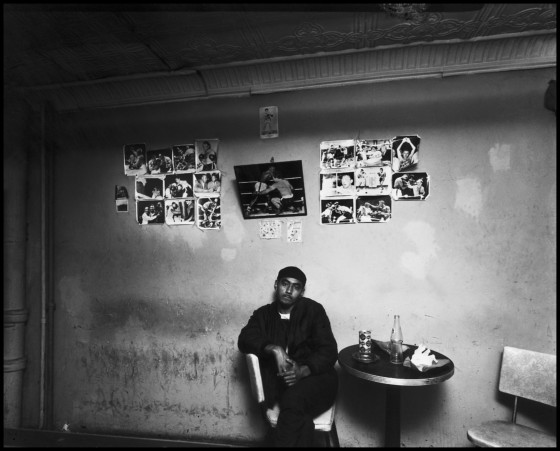

Bruce Davidson is most well-known for the images he took in inner city New York, from the late 1960s, through the 70s and 80s. For him, the broader political climate of the era felt urgent and cried out for documentation. With all that was going on in the States and abroad, such as the war in Vietnam, American space exploration, and the civil rights movement, he could have chased a number of stories, in a myriad of locations. Instead, he chose to turn his lens to his own backyard, showing the plight of impoverished inner city residents within the context of this global turmoil.

Here, Davidson explains the genesis of this career-defining project.

“In 1966, I began to document the neighbourhood in Spanish Harlem known as ‘El Barrio.’ At first, I met with the local citizens’ committee, Metro North, to obtain their permission to produce a document that would serve as a calling card to be presented to local politicians, prospective business investors and the mayor. The community workers took me around to meet and observe people living in abysmal housing.

I witnessed people working together to improve lives and create a place of peace, power, and pride. At that point in American history, we were sending rockets to the moon and waging a futile war in Vietnam. I felt the need to explore the space of our inner cities and document both the problems and the potential there.

I photographed the people of East 100th Street and their environment in an open ‘eye to eye’ relationship, using a large bellows camera with its dark focusing cloth. I carried a heavy tripod and a powerful strobe light along with a portfolio of pictures taken in the community. As I stood before the subjects, the physical presence of the classic camera lent a certain respect to the act of photography, placing me in the picture itself.”

Under-reported news

Whilst big news stories require thorough documentation, to find stories that truly resonate, paying special attention to smaller, less widely reported news stories can pay dividends.

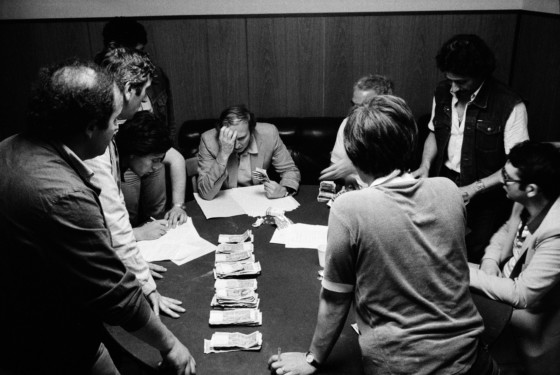

Patrick Zachmann’s seminal Naples work was inspired by a small news story that had, so far up to that point, not had very much coverage in the international press. His interest piqued, he decided to investigate further, resulting in his seminal immersive documentation of the Naples mafia and police.

“The first real story I did was on the Naples mafia. I was reading the newspaper in France at that time, which said that there was a gang war between two main families in Naples, with 400 dead in a year. At that time it was the Lebanon war and all the reporters were going there. I didn’t want to follow the same route, but I did want to confront the violence I had read about. I was young and as a photojournalist I wanted to experiment and push my limits.”

Read more about Patrick Zachmann’s approach to photography in ‘Storytelling: the Single image vs the Series’ here.

Beyond the comfort zone

Whilst following in the footsteps of other photographers can be a good way of learning and developing your practice, breaking away from a well-trodden path can enable you to develop a new niche that is truer to you.

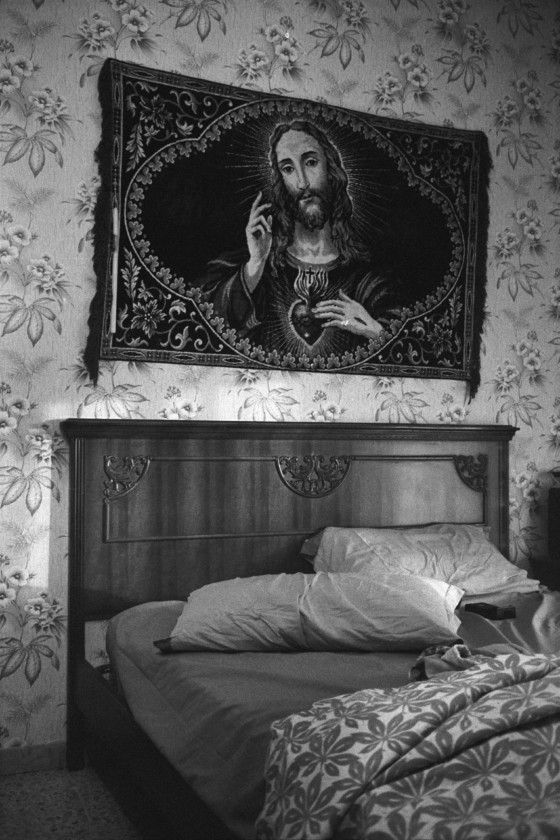

As a young photographer Bieke Depoorter struggled to find her niche, and tried her hand at street photography, which she never felt truly comfortable with. “I was always trying to be a street photographer but I felt like I was stealing people’s pictures, in a way.”

Her breakthrough came when she pushed herself outside of her comfort zone, travelling to Siberia, where she knew nobody and did not speak the language: In 2009 Bieke Depoorter travelled through Russia, photographing people in whose homes she had spent a single night, for her graduating project Ou Menya, which won several prizes, including the Magnum Expression Award, and led to a book, published by Lannoo in 2011.

“I wanted to travel on the trans-Siberian train and stop in small villages and photograph there,” said Depoorter, speaking at the Magnum Photos Now event. “I didn’t have money for hotels and in the places that I wanted to visit there were often no hotels, so I asked the first girl that I met in Moscow who spoke English to write me a letter that said ‘I’m looking for a place to sleep’ so that I could find a place at night.

The first night, I ended up in small village and it was getting dark so I showed the letter to people to find a place and some people took me in. It was an eye-opener because I took pictures and finally I felt comfortable with photography…When I was staying the night people really opened up for a few hours and I could take pictures of very intimate moments. I thought that maybe I should do it every night and focus on the intimacy of families and see what happens during my trips.”

Read more about finding your documentary style here.

Pinpointing your passions

You may have found a subject that excites you, and has led to brilliant work, but perhaps it has come to an end or you’ve exhausted the story. By identifying what elements of that project excited you, you can look for those characteristics in new stories.

Jean Gaumy spent years photographing on ships out at sea, very often in rough and dangerous conditions. During this last trip on a Spanish trawler in the North Atlantic, he make a breakthrough, where he identified that the elements that made him passionate about these kind of trips were also present in other areas of vastness where a man can feel the full ferocity of nature in the wild. And so his career-spanning exploration of such places continued with renewed passion.

“I made this photograph in January of 1998 on a Spanish trawler in the North Atlantic. It’s one of the last pictures I took on a traditional trawler. I started photographing on these boats in the early ’70s because I really wanted to be in the middle of the sea and the elements. This kind of boat, with an open deck, undergoes all the chaos and violence of the water and sky. The experiences defied my expectations. And I suffered sometimes.

I did not know that this trip would be the last trip. It represents the end of something, but also the beginning of something else, another cycle. I turned away from the sea, and toward the mountains. The sea and mountains are very similar in some ways in their relationship to the world, to the universe. The tiny, fragile spaces in them, which serve as shelters: the roof of a boat, the bridge of the trawler, the mountain refuge, the tent clinging to a ridge. It’s a spiritual and physical experience, being in the middle of the vastness.”

Love

A timeless source of inspiration that charts back to the very beginnings of story telling and art, love or a muse can change a photographer’s outlook and approach to their work.

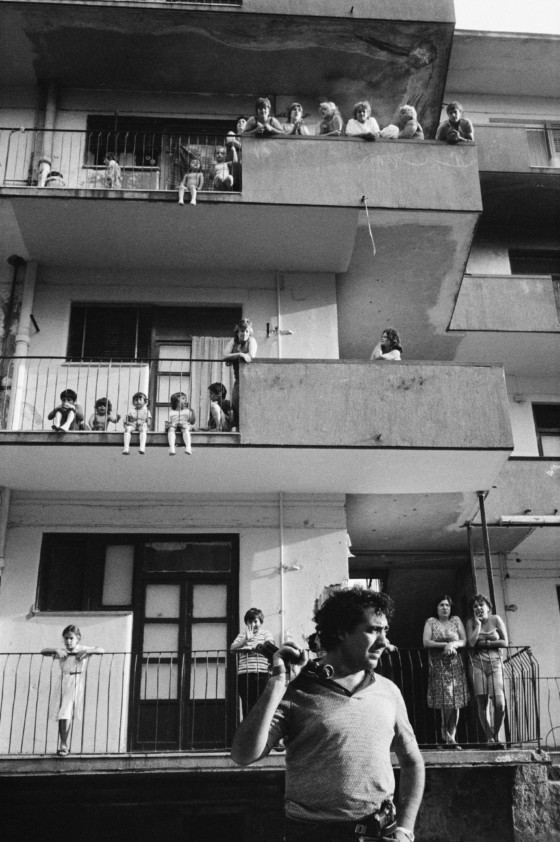

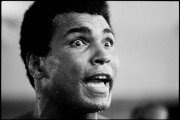

Jacob Aue Sobol’s deeply personal work became truer to himself when he fell in love with a muse – Sabine – who gave Sobol’s work a softness and a raw intimacy, which he described in 2015, in reference to the above image.

“When I fell in love with Sabine and she taught me how to dance. After that moment, I stopped taking pictures to prove anything or to be daring. After that moment, I started taking pictures out of love and curiosity. After that moment, I started dancing. Sabine had put on lipstick, high heels and a polka-dot dress. It’s was the christening of her sister’s first baby.

‘Peqqeraava? Am I beautiful?’ Sabine asked. She lifted her skirt, revealing her star panties and a pair of laddered tights. ‘Lorunaraalid. You’re wonderful.’ I replied, grabbing hold of her and starting to dance.

I’ve often watched Sabine dance at the village hall without wanting to join in. But now that we’re alone in her uncle’s house, I surrender to both the dance and Sabine. We danced across tables, chairs and mattresses. Wilder and wilder. Through the open window we can hear the church bells chime but Sabine insists: ‘Aamma, aamma, qilinnermud ilinniardiiatsiikkid! More, more. Let me teach you how to dance!’”

The book Sabine, A Love Story, is a testament to this transformative relationship. A sense of emotional exposure has been characteristic of Sobol’s work ever since. With And Without You, a book published in 2016, is Sobol’s reflection on 20 years without his father as he reached 40 years old himself. “The book is a tribute to him, and all the emotions and anxiety churned up in the wake of his death,” he said.

Read more about the practice of Magnum photographers in Theory & Practice.