The Future of the Photobook

What will the photobook of the future look like and how will it survive in a saturated market?

The photobook has historically been underrated in its contribution to the evolution of photography, and only in the past 20 years has it started to be taken seriously as a medium. Martin Parr, an avid photobook publisher and collector, has had no small part in cultivating this awareness. Today, the photobook has come so far that there are books about photobooks charting their history and creating essential archives, such as Phaidon’s recent Magnum Photobook: The Catalogue Raisonné. As photographers increasingly publish their work in book format, the question is raised: how will the photobook adapt to survive in a rapidly changing – and quickly saturating – market?

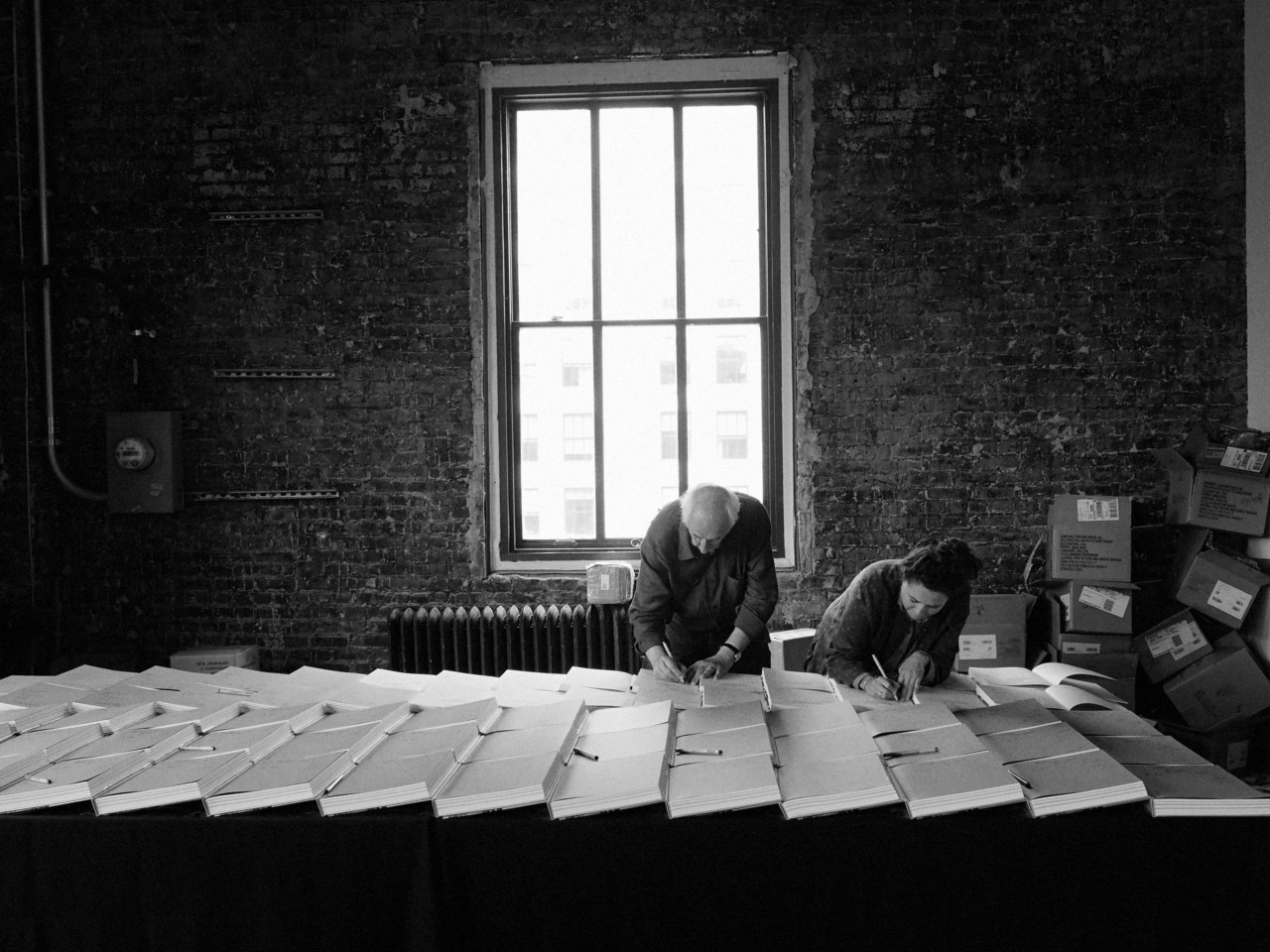

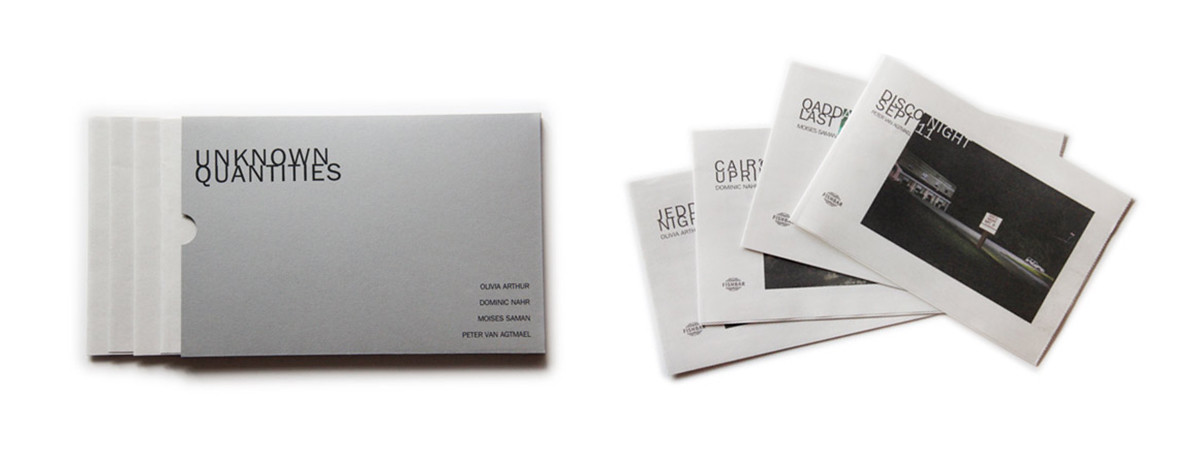

At Magnum and the International Centre for Photography’s day-long symposium on the photobook in New York in June, Magnum photographer Martin Parr, Olivia Arthur, Magnum Photographer and co-founder of gallery and book publisher Fishbar, Aperture’s Creative Director Lesley Martin and Fred Ritchin, Dean of the School at the International Center of Photography, sat down together to talk about the future of photobook publishing. The panel discussed issues such as audience, financing, self-publishing and collaboration. Here, we present five broad conclusions or considerations for the industry and photographers alike, selected to shape thought around what the future of the photobook might look like.

Bad books matter too

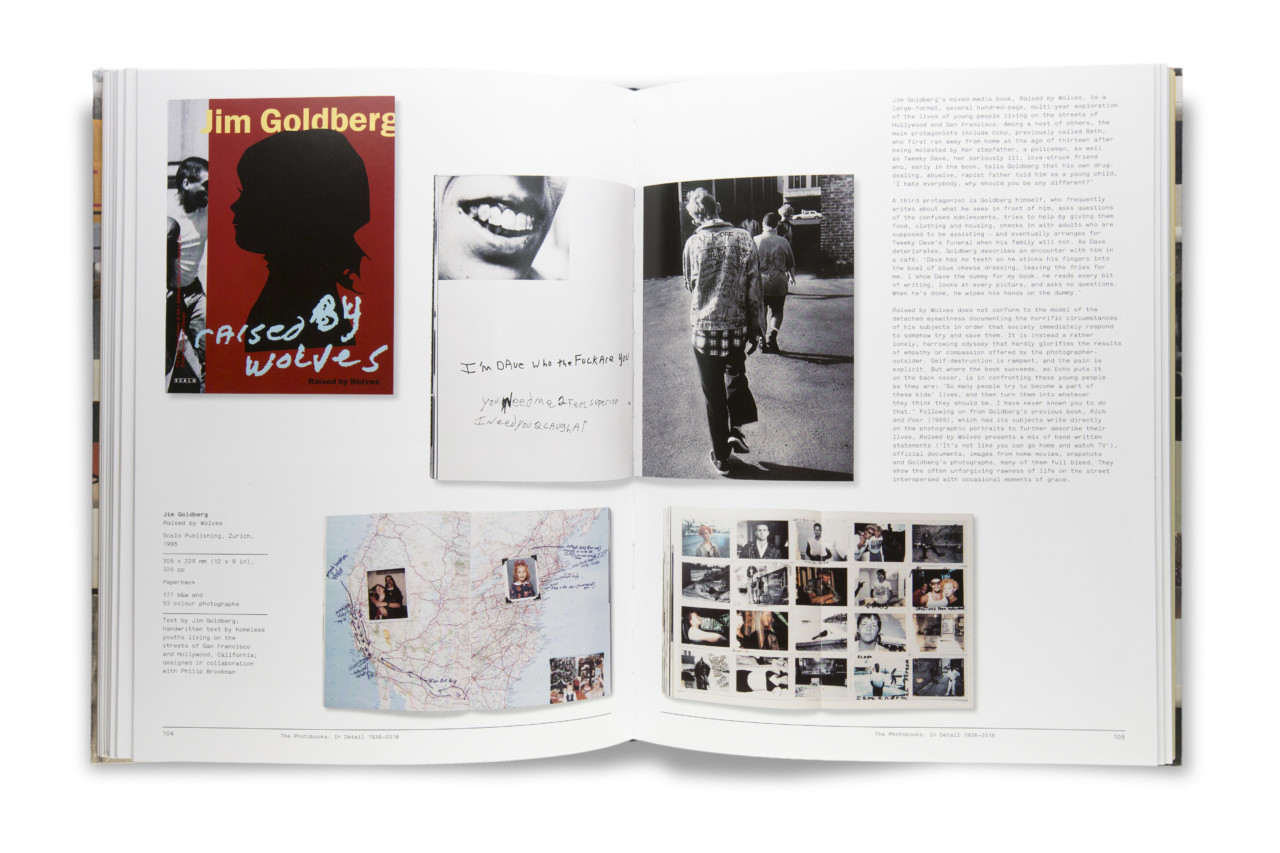

Self publishing and print-on-demand may be to blame for the proliferation of thousands upon thousands of photobooks flooding the market, but instead of seeing this as a death knell for the medium, Martin Parr argued that especially innovative books still stand out against mediocre photobooks, the abundance of which only emphasizes the achievement of those that are truly fresh and exciting.

“Photography is the easiest thing in the world but also the most difficult. It’s very easy to take a body of work and in an afternoon turn it into a book that looks contemporary and exciting but it has no soul, no message, no real substance. People believe they have made an important contribution to photography but they haven’t,” said Martin Parr.

“A lot of books are very bad and we need these to understand a good book, because when a good book rises above the flotsam and jetsam of all of the stuff out there you really notice it. We need these lists – best of books and awards and prizes – because these are the ways that the achievements of photography publishing can rise to the surface. We need this guidance to understand what is actually interesting and good.”

"Photobooks are having a golden era but the concern is that we are making them for each other"

- Fred Ritchin

Breaking out of the photo-ghetto

For many photographers, the fact that other photographers and professionals in the industry like their work can feel like a huge achievement, even vindication, but the need to look outside of the photo-community in trying to reach an audience for books is more important than ever. Doing so invites a wider audience, one interested in the issues explored within the book, rather than just the photographer who created it.

“Photobooks are having a golden era but the concern is that we are making them for each other,” Fred Ritchin said. “It’s not sufficient to just talk to each other at this point. I’m looking for something that restates where we are in different ways.”

“I think we see this big cloud which is the photobook audience and what’s interesting is trying to go out and think about things differently and saying I’m going to reach these people because this is what I want to do,” said Olivia Arthur. “We aspire to be like each other, too much so.”

“We need to think about how to incorporate other audiences into this ecosystem and to think about those audiences when making books as well,” added Lesley Martin.

Expanding markets and territories

While Europe is arguably ahead of the US in its acceptance of the photobook as a medium unto itself – through the proliferation of photobook publishers and fairs – one thing we will continue to see in future are other territories around the world making meaningful contributions to the medium.

“One of the positive things is that we are now seeing photobooks coming from all over the world, from where we didn’t think there were any. For example, I’ve just recently bought a collection of 20 books from Indonesia,” said Parr. “We will see other territories get involved apart from the obvious ones and the numbers [of books from these places] will probably continue to increase.”

Uncollectible and affordable books

Given the trend towards collectible photobooks with hefty price tags, we may see more of a backlash and a move towards the opposite of the spectrum, a more democratic view of the photobook that could reach a much larger and more diverse audience.

“I would love to see uncollectible books,” said Ritchin. “I would like mass market, uncollectible books which are made on issues of social interests. A book that’s about current affairs, about what’s going on that a conglomeration of groups, like Magnum, Aperture and ICP, could do together. The collectability mix makes me nervous. A book seems to be about one thing but it’s made to be currency.”

“It has to be affordable. Magnum’s Square Print sale is very successful because it’s affordable. We need to start training people and offering things at that lower price point that can still be really enjoyable,” said Martin.

"People still have a huge desire for the book, for the printed object that they can hold."

- Olivia Arthur

Print will prevail

There is little doubt that the photobook within the history of photography will continue to proliferate, almost as an antidote to the digital era, as people continue to crave the physicality of a book.

“People still have a huge desire for the book, for the printed object that they can hold. It’s exploding in all sorts of different directions at the moment, and there might be a retraction but I think we’ll come through the other side with something more interesting,” said Arthur.

“When a body of work is really important and relevant and touches people it’s eventually going to be published as a book, either initially or inevitably afterwards,” added Parr. “We will need these books to preserve the legacy of the history of contemporary photography. And let’s celebrate that.”