The Golden Age of the Photobook

Charting the evolution of the photobook through a conversation between Martin Parr and David Solo

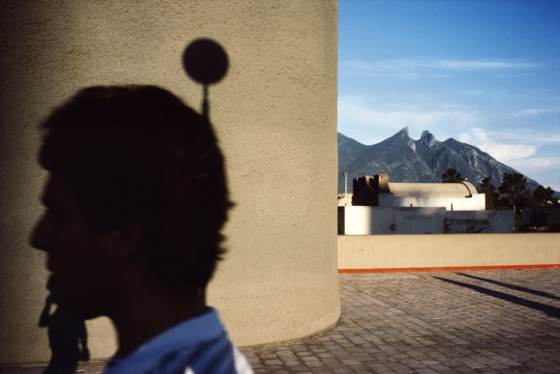

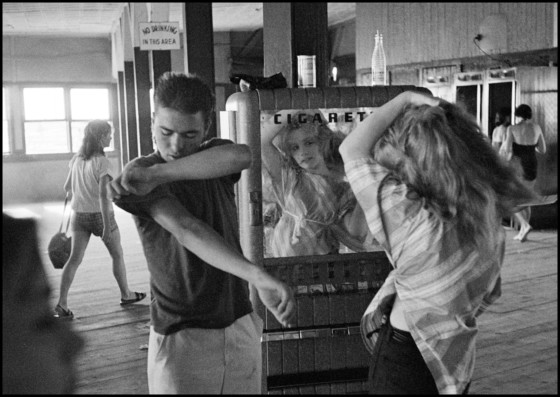

Magnum Photographers

The photobook is the “supreme platform to disseminate work,” declared Magnum photographer Martin Parr, thus opening a conversation with noted fellow collector David Solo at the ‘Magnum Photos Now’ event at the Barbican, London in November 2016. This preamble leaves little doubt as to Parr’s enthusiasm when it comes to photobooks, but belies the vastness of the photobook market, and the attendant, ever-growing, body of books about photobooks.

Martin Parr is known to be a collector of photographic objects, from postcards to watches and assorted political ephemera, but his photobook collection is of particular note. Driven by this interest, he realised that photobooks lacked recognition and status. To redress this, Gerry Badger and Parr undertook to document a history of the medium in three epic volumes (The Photobook I, II and III), published from 2004 onwards.

In 2016, Magnum and Thames & Hudson joined forces to publish an unprecedented and in-depth catalogue of photobooks published by Magnum photographers. The tome Magnum Photobook: The Catalogue Raisonné reveals the photobook as the photographer’s primary vehicle for long-form storytelling. Parr featured on the advisory committee for the project, in a constant dialogue to choose a single book from each photographer to feature.

Much helped by the advent of digital, Parr admits we are now in the “golden age” of the photobook. But how did we get here?

The renaissance of the photobook

Hiroshi Hamaya once made a book and gave it as a gift to all the people who attended his wife’s funeral. This anecdote points to the weight the photobook carries as a mode of expression.

The essential role of books is to get the work out, to have the work seen. Practically, books have a wider viewership than fairs; they can cover diverse geographies. Magnum’s Alec Soth first book is memorable: a digital dummy for Sleeping by the Mississippi, which publisher Steidl initially launched as a trade book with only 1,000 copies, effectively launched his career in a single move. Parr describes it as “spectacularly good book”. It remains true that good books can have a huge repercussion on a career of a photographer. More recently, Cristina De Middel’s Afronauts gave the heretofore unknown artist pre-eminence; her sold-out, self-published book is now an expensive rarity.

In parallel, since the late 1990s, photobooks are of growing importance of to cultural institutions. Where only just two decades ago, book publishing was a rare occurrence for museums, it would now seem utterly unthinkable to do a retrospective or group show in a museum without an attendant book. Museums and galleries must now also focus on solving the inevitable problem of how to show photobooks in exhibitions, spurring new debates, scholarship and research, as the realisation grows that books complement the study and collection of prints.

The advent of self-publishing has created a huge diversity in the space, and this, in turn, can be attributed to technological changes having put the means of production directly into the hands of artists and photographers. Significant evolutions in printing and distribution, mainly attributed to digital capacities, meant more options became accessible at a more affordable price. Following a surge of artist books and photobooks in the 2000s, small indies and large traditional publishing houses alike now contribute to a yearly explosion of photobooks.

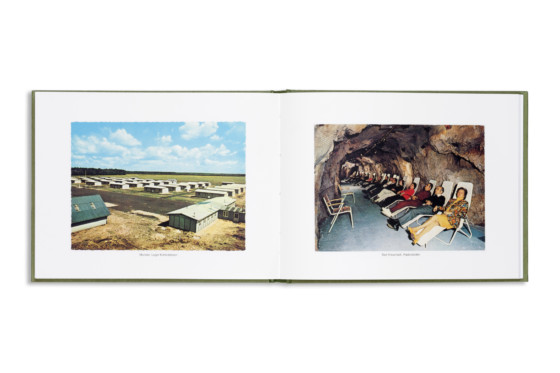

Traditionally a Euro-centric practice, photobook making is now opening up. Pockets of self-started photobook-making communities are appearing; Parr and Solo point to China and India for their emerging scenes, and hark back to the past photobook movements that most inspired them: the Japanese photo books of the 50s and 60s which were a “revelation” for Parr; the Latin American scene which Solo is involved in with the 10×10 project.

The making of a photobook

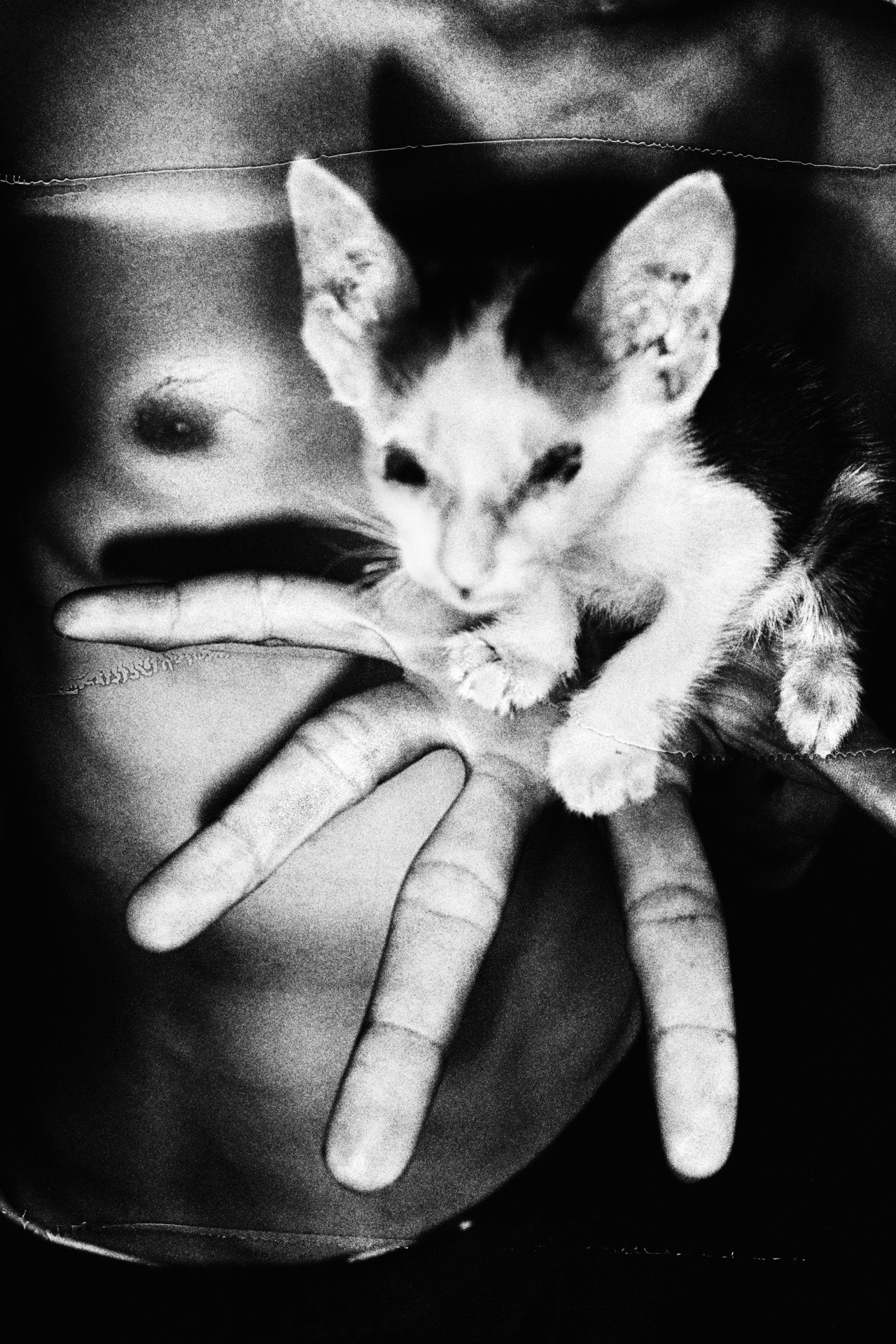

When asked why making photobooks matters to him personally, Parr remembers an earlier part of his career, when his anti-Thatcher politics found expression in photography, which became a form of therapy and “a means of articulating something important on a personal level”. Making a book allowed him to express and hold on to the integrity of his idea.

That’s why photobooks take a long time to evolve; they are a process of continual transformation from conception, to selection, and presentation, in order to find the perfect articulation of a personal point of view.

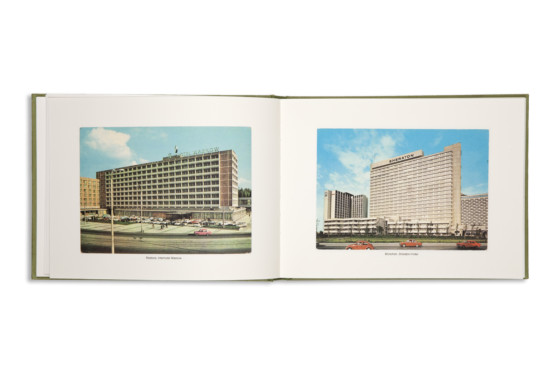

Photobooks are also an intensely collaborative process, working with an editor and a publisher to reach decisions on the sequencing of images, to considerations the impact of a book’s size and paper stock on the physical object-ness of the book, and, of course, on the text accompanying the images. There is a plurality of ways of integrating text into a book, from captions, introductions, essays, forewords and after-words, to deeper partnerships with writers throughout the project’s evolution.

The making of a book cannot be dissociated from the audience the final object is intended for, and indeed, different audiences will influence how books are made. Thanks to technological advances, a wider set of options is available now than ever before, all at the service of the book’s genre and intention, from news and reportage, to advocacy, diacritic journals or portraits of people and place. Self-publishing has come to the fore as a way, which some would consider the best, of disseminating the work and the stories behind each project, with the intention always firmly in mind of going beyond preaching to the converted.

The allure of the photobook

Both Parr and Solo agree that, because there are so many books out there today, a rigorous selection process is key, though Parr admits, “the only way to tell a good book is to see lots of not very good ones.”

And what do these two distinguished collectors look for? One thing all good photobooks have in common is good photographs and something to say, says Parr. He continues, “You can have the language but nothing to say”. With their well-practised eye, they decipher the cover and pick it up to get a feel for its weight and production values. Both are on the lookout for a surprise, something unusual or new, a sense of unfamiliarity that prompts further discovery and investigation, and of course, motivates the purchase. Most importantly, they look for an original voice – something Parr recognises is the most difficult thing for a photographer to achieve.

The engagement with a photobook plays out over space and time. It has a physicality which prints or digital don’t: books can be handled, smelled, shared. Engaging with the photobook is an extended, different experience that plays out over time; and in turn, it is this sense of the duration that allows time and space for ideas, themes, and emotions to develop. As Solo says, “a photobook is more than the sum of its parts or of the images it contains.”

Prizes play an important role in helping discern the future classics and celebrating them as they emerge. For instance, the Aperture Book Prize, announced every year at Paris Photo, creates a shortlist of the year’s best books. Magnum’s Michael Christopher Brown won 2016’s Aperture First Photobook Award for Libyan Sugar.

The photobook’s renaissance has much to thank new technologies for, but its longevity is a mark of the medium’s effectiveness. Indeed, in Parr’s words, “in a throwaway society, it is almost impossible to throw away a book.”

Read about more discussions from the Magnum Photos Now events here.