Power and the Camera: Gregory Halpern on Intuition, Reflection and Representation

The 2018 Magnum nominee and long-time teacher discusses the beauty of books, the craft of photography, and the politics of representation

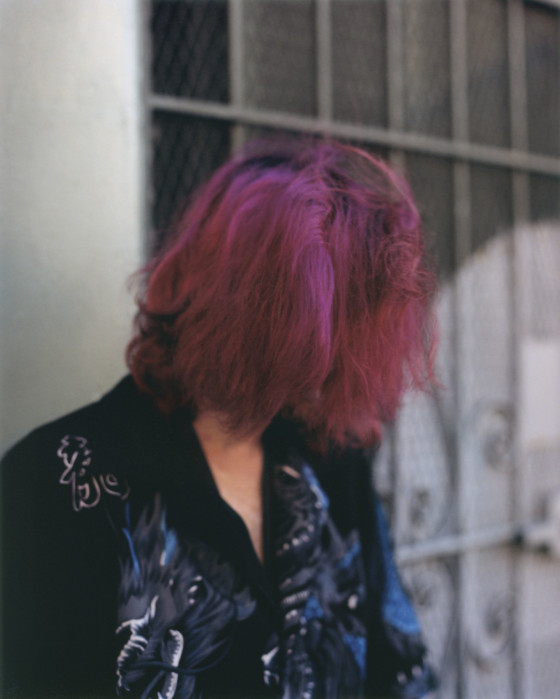

In our final piece in the series introducing Magnum’s new crop of nominees, we explore the work of Gregory Halpern. Based in upstate New York, the artist has a long history of teaching photography as well as making series-based work, often published in the form of photobooks. His acclaimed project, ZZYZX, was published by Mack Books in 2016. With Halpern, we delve into his practice to understand how he engages with the world.

What gave you your start in photography?

I was fourteen and my father brought home a book of photographs called Triptychs by a photographer named Milton Rogovin. Rogovin had worked largely in obscurity into to his eighties, photographing his neighbors in Buffalo, NY (where I grew up) starting in the 1970s. He returned to photograph the same people in the early 1980s and again in the 1990s. The pictures are stylistically modest but just devastating in content. It was the first time a work of visual art moved me to tears.

What are the areas that interest you at present?

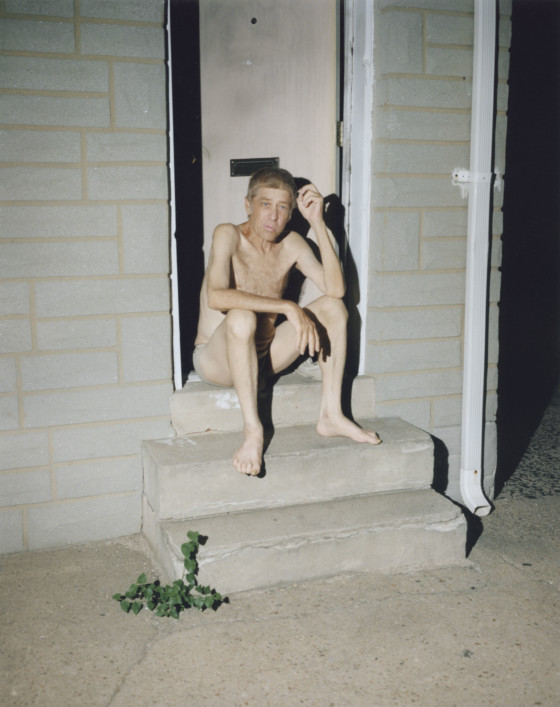

Right now the main subjects that interest me most are class, masculinity, beauty, hope, despair, rage, death and contradiction.

Can you talk us through the craft of your process?

I tend to photograph intuitively, photographing what I’m attracted to. I have a sense of what I’m looking for, but I’m open to what comes my way, which is usually different from what I anticipated. When editing, I slow way down. I sit with the work for a long time. At times, I won’t even develop the film for months after shooting it. I often rely on people to help me edit the work. People who have been immensely helpful to me on that front, for example, are Jason Fulford, Michael Mack and Ahndraya Parlato.

You pay minute attention to color and composition. How important are they to you as visual tools? What do you think of the concept of beauty?

When I was working on ZZYZX, I printed out an early edit of the book on a color laser-printer and sent it to Robert Adams, with whom I have corresponded over the years. He wrote this back to me: “Beauty and its implication of promise is the metaphor that gives art its value. It helps us rediscover some of our best intuitions, the ones that encourage caring.” I couldn’t have expressed that sentiment more eloquently. But yes, I believe in the concept of beauty.

In your photographs, and in particular in the way you edit and sequence them, we often see vibrant, quasi-mystical, sublime compositions, in conversation with images that depict the real in unadorned glory. What is it about these two extremes – the real and the sublime – that is important in understanding your photographs?

I’ve always been interested in how these two ‘genres’ intersect, or are related, although we tend to think of them as separate. I love the way Magical Realism, for example, allows for multiple realities to intersect. I also like when viewers don’t always know how to read work, in terms of where it sits, genre-wise. And I think that approach shows respect for the viewer by forcing them to be an active reader of the work.

Three of your main and most recent projects, A (2011), ZZYZX (2016), and Confederate Moons (2018) all take the shape of photobooks. Can you talk us through the evolution between these projects?

Of these three, A is closest to having a traditional documentary “style.” It’s not straight documentary but it’s deeply influenced by, and indebted to, the documentary “tradition.” I envisioned A as a ramble through a fictional city—a place that was an amalgamation of other places and feelings, and that was heavily inspired by Buffalo, NY.

Over the next five years I drifted towards something else, a way of working that allowed for something more fantastical, which led to ZZYZX, a book inspired by Los Angeles. I wanted to make a book that, in its edit and range, was unwieldy and unpredictable, that struggled to hold itself together and yet somehow does, like the city of Los Angeles itself. I wanted the pictures to evoke something simultaneously contemporary and ancient, a response to the Los Angeles of the moment, but also something not so literal. I wanted the space to also be somewhat mythical, the timeline somewhat Biblical.

Lastly, Confederate Moons was a quick project, an experiment really, so it’s not on the same scale, but I was thinking about Magical Realism, and also trying to make a personal reflection on the state of the nation at that moment. The summer of 2017 was a strange and painful one for the US, full of tension across race, class and gender lines. There was a full solar eclipse nine days after a white supremacist drove his car into a crowd of peaceful protestors in Charlottesville, VA. The country felt like it was being ripped apart and yet the entire nation was staring at the sun, reveling in the apocalyptic thrill of watching the moon temporarily extinguish our life-source, all together. It was such a strange moment, and the book is a response to that moment.

ZZYZX was the top of many best photobook lists in 2016. Looking back, is that something you had anticipated, for example, was it the culmination of a specific process or cycle of work? Has its reception changed anything about your practice?

I had no idea the book would resonate the way it did. It was a pleasant and weird surprise, and I still wonder why people seemed ready to see that work at that moment. I don’t think the reception really changed anything about my practice, but maybe it allowed me to trust myself a little more when making new work, and for that I’m grateful.

Is the photobook the best format for showing your work?

It definitely is. I love the space between images. The things that happen when you turn the page, when you are looking at a new image with the ghost of the previous image lingering in your mind… I love the feel of a being swept up, as if by a stream, by a book of photographs. I love the introduction to Rinko Kawauchi’s book Illuminance, in which David Chandler writes this beautiful and simple meditation on books in general: “There is something primal in the act of opening a book for the first time. That moment of expectation, that prospect of discovery, however dulled or wearied, is still there each time we take a new book in our hands. At our most innocent and instinctive, we are prepared to be changed in some way by what we are about to see.”

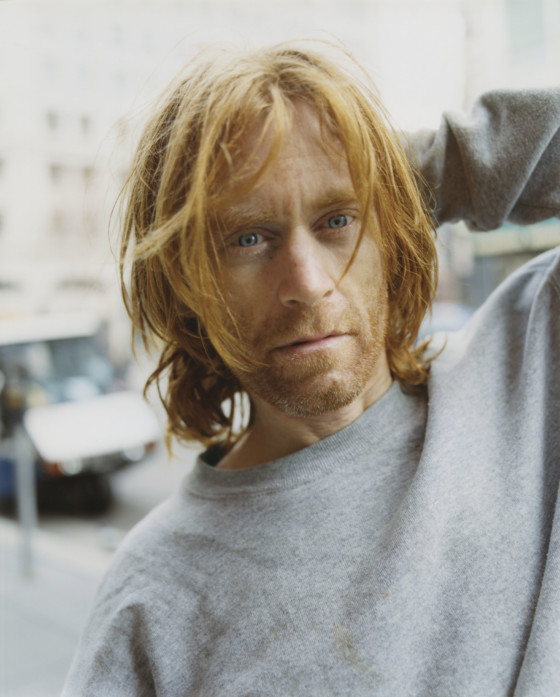

Amongst landscapes and details of daily life, your books also often feature characters, whose gaze interrupts the sequencing of images, arresting the viewer with direct eye contact. It seems they serve a sort of performative role, bringing the viewer closer in, demanding that we pay attention. What is the role of figurative representation and portraiture in your work and how do you choose your subjects?

I think the portraits are really the backbone or the building blocks of the work, and the landscapes and details sort of hover around them, filling the spaces between, fleshing out a narrative and creating a setting. I tend to not like the way my work looks when it’s edited to be all one type of picture or the other – just portraits or just landscapes. As for how I choose my subjects, I’d say they are people I want to keep looking at and thinking about, and whose likeness I continue to find interesting, compelling or beautiful even after looking at them for many months or years.

You have been teaching photography at university level for many years, and your book, The Photographer’s Playbook, co-written with Jason Fulford, brings a playful edge to photographic assignments, in a bid to diversify photographic practice and to encourage practitioners to try new things, but also, to work hard at becoming photographers. What is most important to you about teaching photography? What is missing from students’ work? What would your best piece of advice be?

I’ve been lucky enough to be at the Rochester Institute of Technology now for almost ten years. It still amazes me that I get paid to look at pictures and talk about them with other people who love pictures. It’s a very privileged position to be in, especially at a place like RIT, where the best students are really remarkable. I care less about talent than I do about passion, curiosity and engagement. If I had to generalize about what is missing too often from American students’ work, it would be content, simply put. Sometimes students are so well-versed in aesthetics and trends, or in their own emotions and lives, that the pictures are all style and feeling, no content. I’d prefer that students point their cameras at interesting content in an artless way than make photographs of beautifully-seen but relatively insignificant details.

You have range: geographically, thematically, and visually. How do you choose your subject matter? What needs to be looked at, photographed and why?

What’s interesting to me about the world is its chaos and contradictions, the way opposites can be so beautiful in relation to each other. I like how you can be attracted and repelled by something at the same moment. I want my images to create cognitive dissonance. If I feel that a sensation caused by an image is singular in nature—awe, beauty, dread, for example—I wind up finding the image to be manipulative, and unfaithful to the contradictory natures of reality. I think we underestimate our viewers’ and ability to read the work.

How does your work fit into the current politics of representation, and what is photography’s role within these?

It’s a great question and it’s really important to talk openly and honestly about this. I am a white man with institutional support, and all the privileges and benefits therein, and yet some of my projects look towards those on the margins and the disenfranchised. The first thing I’d say is that I think about this fact all the time. I question why I feel compelled to make this work, and whether I have the right to do it. And depending on the day, my answers to these questions can change.

I think the recent criticality about how we represent one another across lines of class, race and gender is long overdue. It’s important to talk about power and the camera, and for that matter, who is and who isn’t able to navigate with ease the art-fraternity of power brokers and the elite social clubs of collectors and curators, etc. The art world can be a profoundly alienating and exclusive place, obviously, and it is worse for female artists and artists of color.

As for my own work, there are times I worry how it will be read, although in truth, I’m interested in creating work with contradictory degrees of discomfort and reassurance built into it, and so I accept the fact that the work will make some people uncomfortable. My first book, Harvard Works Because We Do, had a specific political agenda and was designed to help the service workers of Harvard University win a wage increase. It was perhaps the most “comfortable” work of mine to view because the text and the overt moralizing agenda of the work left no room for interpretation or discomfort.

Since then I’ve come to feel that an artist’s only “responsibility” is to illustrate and articulate their own vision and sensibility. I’m no longer a big believer in telling artists, or anyone, for that matter, what they should or shouldn’t do. Should artists only make pictures of people who look like them, sound like them, have shared histories, etc? People can disagree about this, but for me the answer is no. Call me naïve, but for me there is something transcendental in the power of story, and there is something mysterious and hopeful when one stranger looks into the face of another stranger (via portraiture) and feels something. If we are going to question artists’ ethics (although I’d prefer not to) why not question the ethics of escapist abstract work, or work exclusively about the photographic process, or work made to decorate the homes of the uber-rich while the poor get poorer and the rest of the world burns?

And what does it mean if work about the poor or marginalized does not upset? If it upsets, is it because the work points to uncomfortable realities? Is it because the artist has used their subject in a way that is uncomfortable or exploitative, or has profited from making their likeness? Is it because the artist has implicated the viewer, as a guilty party? Distress from looking at work is often hard to articulate, understand, and specify, but I think there is a more nuanced conversation to be had, if we are willing to sit with, interrogate, and even appreciate discomfort.

It’s not an easy conversation because of the facts of poverty and marginalization and because of the history of how cameras have been used. The colonialist history of white men travelling to places “owned” by their countries and photographing the “natives” is troubling not just because of the power imbalance between subject and photographer, but because it lays bare a dynamic that still exists, albeit in a less obvious way. This history, compounded by generations of institutionalized racism, haunts all photography. And it haunted me while making ZZYZX. And yet I knew that I wanted the book to be representative of Los Angeles, a city in which whites are only 29% of the population, and where 2.6 million residents (or 27% of them) live in poverty (less than $11,880 a year for an individual or $15,930 for a couple). I was particularly struck by the reality of those facts in contrast to the white-washed vision of America created by Hollywood. By ignoring that reality I could have avoided questions of representation, but to ignore it felt equally suspect/complicit. It’s all immensely complicated and fraught, but for me, I come back to the belief that to avoid making the work, for the sake of avoiding the conversation, is not a solution.

What is your stance on the traditional role of photography as record keeper, a representation of reality, however subjective?

Over the last 15 years, I sort of drifted away from my attachment to the idea of photography as record keeper, but I have been moving back to an interest in it recently, with both a renewed respect for its power to do so, but also perhaps with a more informed sense of its limitations. The swing back that way, I think, has something to do with the politics of the moment, the desire to engage, uncomfortably, with our reality. But the question of photography and reality is such an amazing one. For me, what makes photography such an exciting and troubling artform in general is the deception and tension hard-wired into it, the difficulty of defining its slippery relationship to truth. A photograph has potential to be much more objectively truthful or factual than, say, a painting, but painting is more honest about its intentions and possibilities. What I respect, and at times envy, about painting is that it never claims to be anything other than a purely subjective vision. And we place no false expectations on it in terms of its truth value. Photographs, on the other hand, are truly never entirely fiction or non-fiction.