“I can work with no talent, I can’t work with no commitment”

Discussing the perennial challenges of teaching documentary photography with Magnum's Stuart Franklin

Stuart Franklin’s book, The Documentary Impulse, explored the underlying human impulse to document, from cave painting through to modern photography. In his teaching he aims to convey the weight of this hard-wired obligation to his students, and to focus on the importance of storytelling, of making a connection with an audience, over the fine points of technical process.

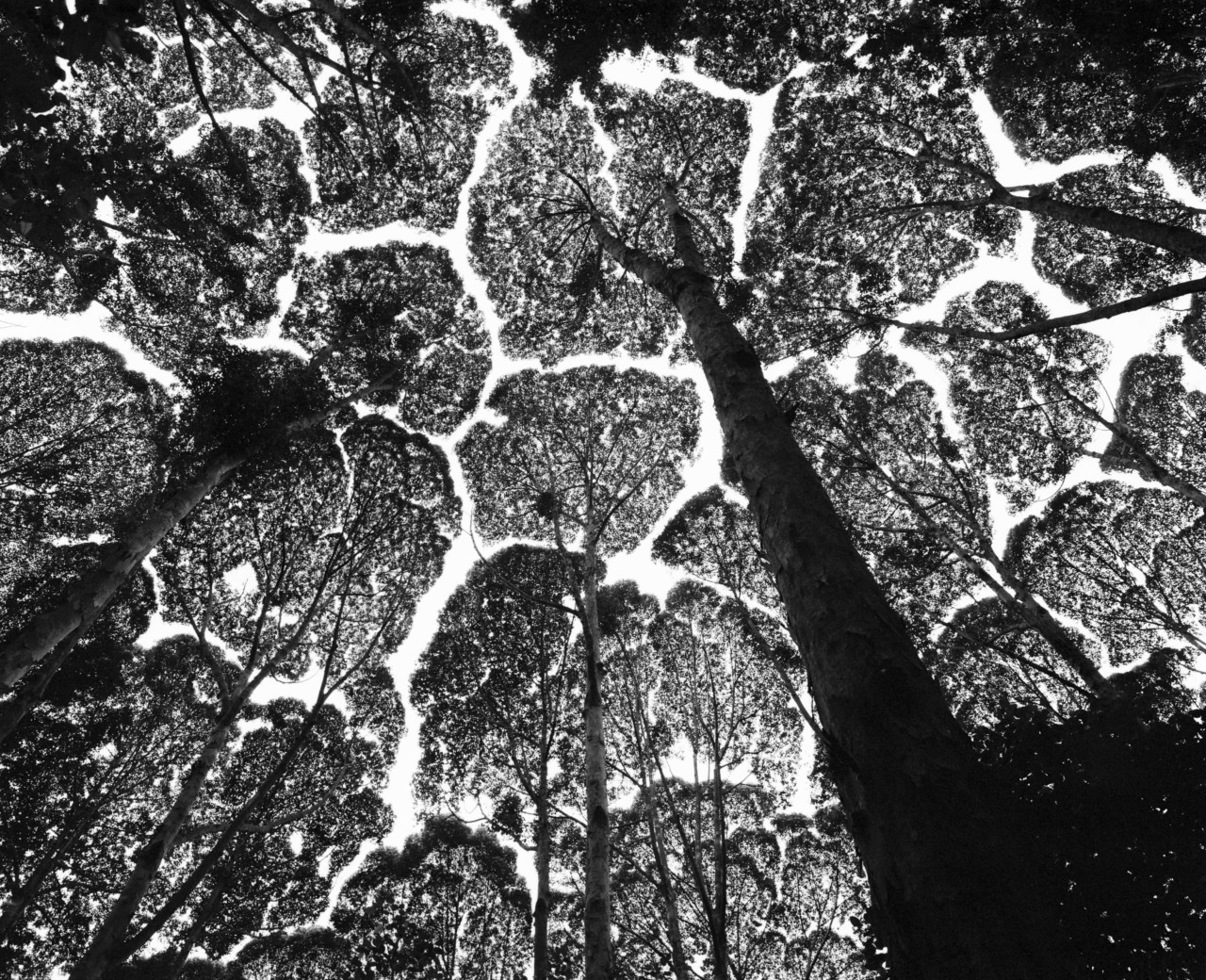

While the subjects Franklin is famous for documenting vary hugely, from the Troubles in Northern Ireland to famine in Sudan, through to his more recent work on humanity’s relationship with trees, there is a consistency in his approach – a practice focusing on consideration and gentleness. Having studied fine art before settling upon photography, Franklin’s approach to teaching comes from a classical standpoint where the refinements of technique can be taught, as long as two essential qualities are present in a student: sensitivity and commitment. Working out an approach, in short, is more fundamentally challenging in story telling than refining a style.

Franklin will be one of the Magnum photographers teaching on the 2018-19 Spéos Photo School course on Creative Documentary & Photojournalism in Paris.

What do you see as your primary obligations as an educator?

I am very conscious of the fact that young people put a lot of store, and a lot of trust in an educator, in someone that they look to for guidance. I take that trust very seriously. I have heard too many stories of teachers overlooking work, or not taking it seriously enough. Of course the seriousness with which students go out and take the work is also important. I would say I try to be encouraging, it’s been said before that 90% of education is encouragement, and I think that’s probably true. I always look for the opportunity to progress meaningfully with a project.

And sometimes students feel a bit lost, because they are trying to find themselves through the photographic work they do. I also try to support them in that.

Do you think that’s something that’s quite specific to photography, and teaching photography – that idea of students using it as a means of self-discovery?

Not within the arts, really, no. If you are a sculptor, painter, or creative writer then the process would be the same, and the mode of guidance would also be the same. I don’t think photography is any different in those terms. It’s about getting a sense of what the student is trying to do and supporting them to do the best they can within the path they have carved out for themselves .

How much do you think coherence is important. Is that something that younger photographers are often missing, or need to develop?

Well visual coherence is one of the talks that I give students, but I don’t necessarily think that it’s an area young people are particularly lacking in. I think that coherence comes in really making the jump from the single image to a multiple image form of storytelling. With a single image – it’s the sort of thing you get more and more on social media – it’s very hard to get a sense of who the person is, what the story’s about, what the voice is. When you start to put a body of work together, say leading toward a photo book or exhibition, then there has to be an authorial voice underneath that work. Visual coherence is all about finding that author, or that voice.

Do you think that there’s been any sort of fundamental change over time, from say, 20 years ago when young photographers primarily thought in terms of books and exhibitions, to now when as you say, the focus on single images or different formats for work? Does the importance of a body of work need to be reemphasised?

It’s very hard to say. People I have grown up with or seen or taught, as photographers, have often gone on to make documentary films. Photography, or documentary photography, is a starting point to a number of different end points. And those end points can vary hugely depending on the story and audience and so on.

There is an awful lot of bendability within media right now, twenty years ago there was a lot of, in a sense, artificial segregation between different visual media And now there is much more convergence. The idea of photography with sound and moving image, of painting for lack of a better word, all sorts of things are starting to wrap and converge and create opportunities for meaningful expression within the broader envelope of photography.

More people are looking at found photographs too, from archives or the internet, to form part of a narrative that is meaningful in a different way.

What other developments or trends in terms of outlook and approach have you witnessed in teaching students, and what challenges do they pose?

I think there’s much more personal work now than there was 20 or 30 years ago. People would see themselves going out into the world as a foreign correspondent before, even if they were only going to the next town over. I think today much more people are digging into their own lives and experiences and trying to make that jump – the synechdocal jump – between the particular and the general.

Sometimes it works, and sometimes it needs more work. Without work it can just become ‘John’s Story of Collecting His Trains When He Was A Kid’. You have to make those personal stories relevant and draw people in, draw an audience in. These personal stories can’t just be there just because you saw a famous photographer do a story about his one-year-old son, so now you want to do one and are expecting everyone to do double backwards summersaults in admiration.

I think these personal projects have got to transcend and communicate. Much as if you were writing a very personal screenplay or novel, it’s got to touch some wider issues, about growing up, childhood, whatever. And if it doesn’t do that convincingly then it’s not going to fly. A personal project has got to have that reach. And I can work on that with students.

So if that can be worked on and can be taught to an extent, what are the recurring challenges that are harder to overcome?

I think there are two fundamental stumbling blocks, and they are usually stumbling blocks I get over at the stage of recruiting students. One is sensitivity, and the other is commitment.

When I am looking for a student it’s someone who has those two qualities, in spades. If they do then I can work on technique. I mean, John Lennon could hardly play a guitar when his mother was run over by a bus. But he was so moved by that event, which took away part of his childhood, that he taught himself to play the guitar and to write, so that he could express himself. Lennon didn’t have innate musical talent, he had conviction and drive, that’s what made him, and what made the Beatles.

I can work with no talent, but I can’t work with no sensitivity, and I can’t work with no commitment.