John Morris on Photo Editing

The legendary photo editor discusses editing alongside Cartier-Bresson, the ethics of war photography and more insights from his seven-decade career

Magnum Photographers

*This article was originally published in November 2016. John Morris died on Friday July 28, 2017 in Paris.

London’s Frontline Club – a members’ club for war journalists, photographers and other members of the media covering conflict – was the ideal venue to honour the life’s work of one of the industry’s most prolific photo editors. In October 2016, the venue played host to an evening that gave credit to John Morris for his role in placing into our collective memory images that would come to define public understanding of WW2 and later the war in Vietnam, amongst many other important moments of the past century.

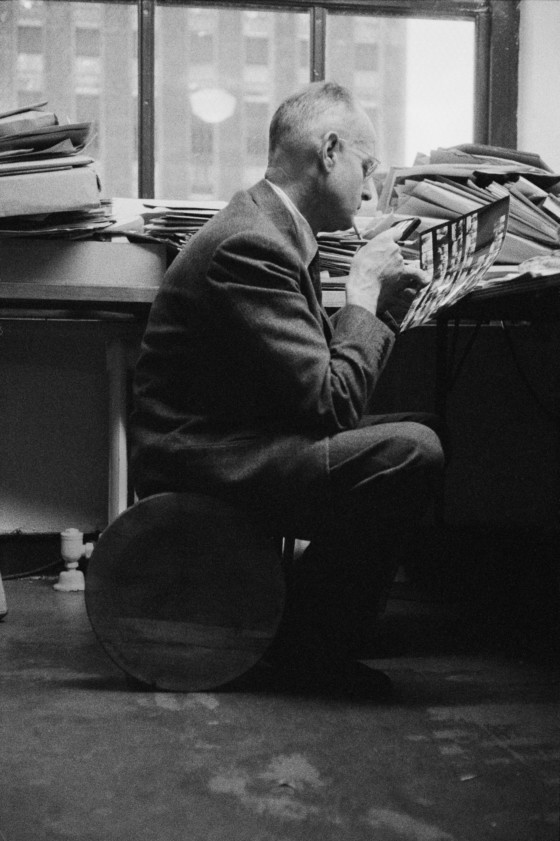

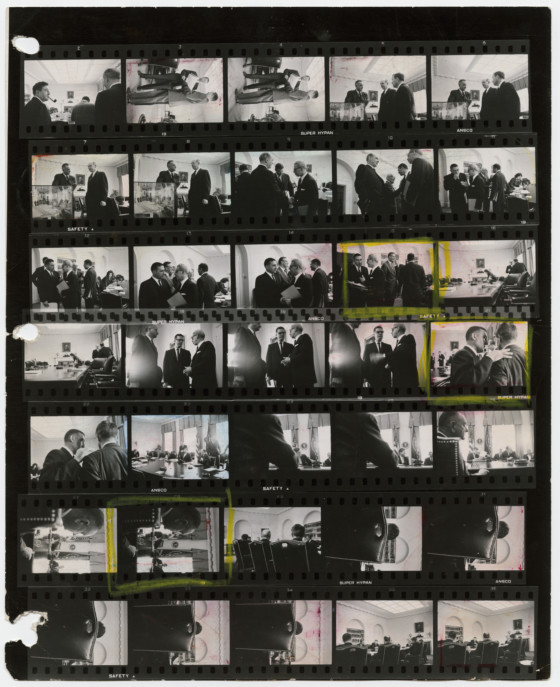

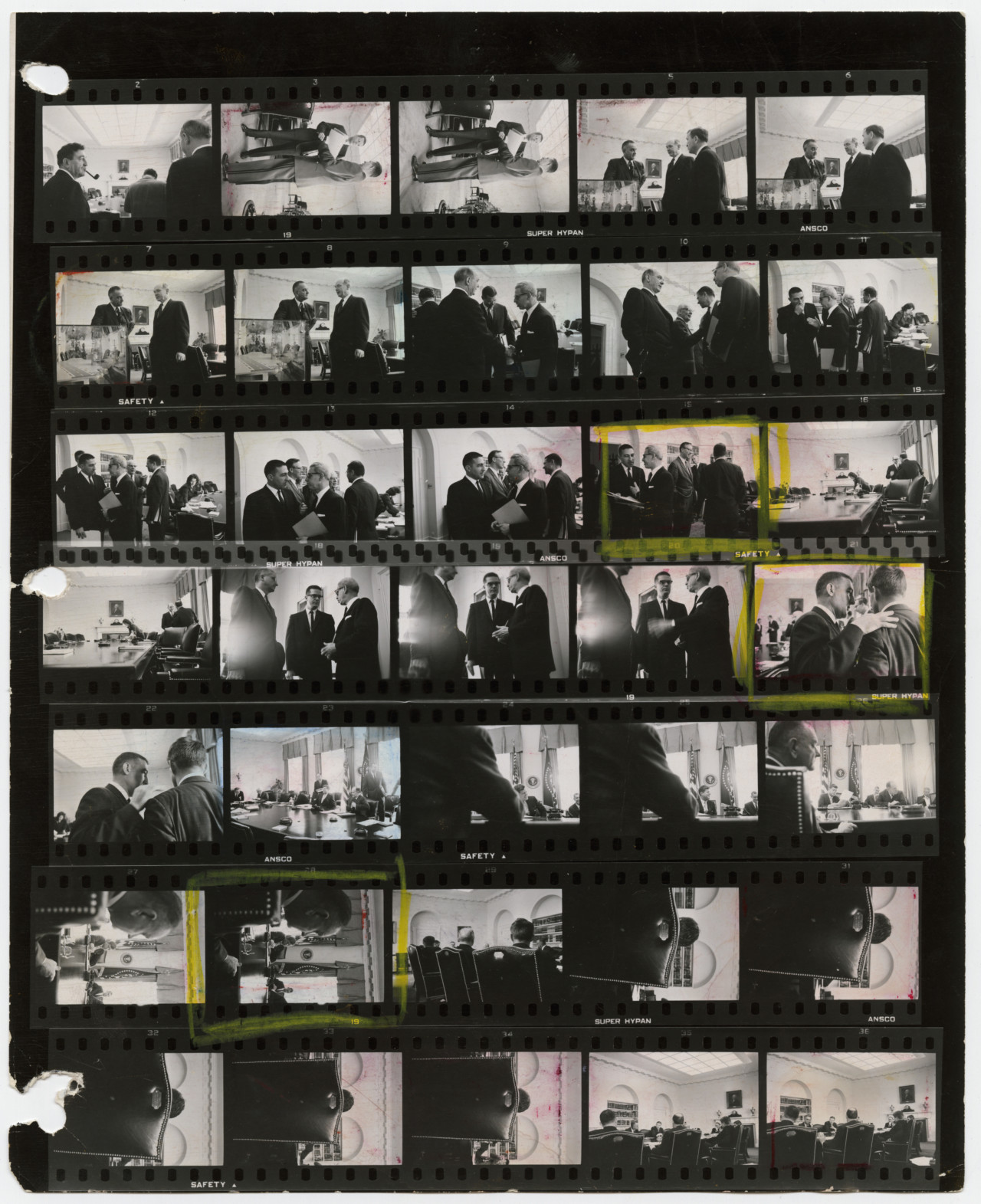

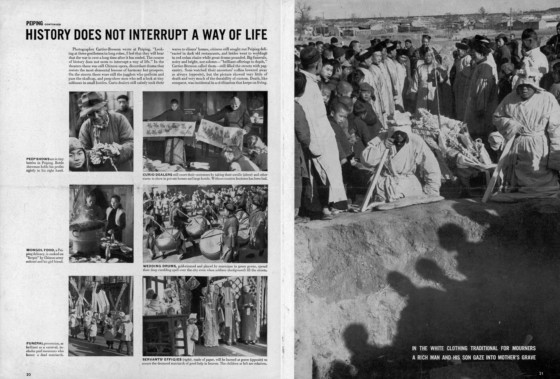

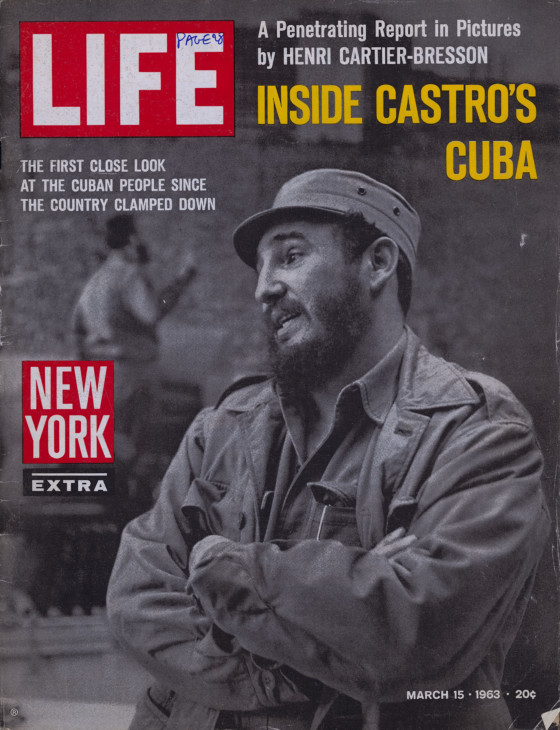

Morris is responsible for the proliferation of some of the most iconic photos in the history of photojournalism. The American-born photo editor was who Robert Capa sent his rolls from the D-Day landings to. He oversaw the production of the 11 images that survived a lab assistant’s processing incident in which most of the rolls were destroyed. He worked as London’s photo editor for the weekly picture magazine LIFE – which celebrated its 80th year as a photo-led magazine in November 2016 – throughout WW2, and then after the war became picture editor for U.S. monthly Ladies’ Home Journal, Executive Editor of Magnum Photos, Assistant Managing Editor for Graphics of The Washington Post and Picture Editor of The New York Times, as well as going on to work as the European correspondent of National Geographic.

While visiting London from Paris, where he now lives, John Morris spoke to Magnum, an organization of which he knew each of the individual founders before they even knew each other, when Robert Capa’s dream of setting up a picture agency was just talk between friends. Here, Morris discusses the profession of the photo editor, muses on the role photography has to play in war, and offers some practical photo-editing advice.

What was the photojournalism world like when you started out, and how has the role of the photo editor changed?

The role of a photo editor has changed in some respects because the media has changed. Photo editors originally worked with publications. Newspapers seldom had photo editors per se, the large ones had a director of photography in charge of the photos but the editing was done on the desks by news editors. And then LIFE magazine came along in 1936 and got people excited about photojournalism, and photojournalism became a glamorous profession. Every young photographer, every young person who had a camera wanted to be a LIFE photographer, where you could actually photograph the real world and tell stories in pictures. And through LIFE primarily and its other competitors like Look, the profession of photo editor evolved.

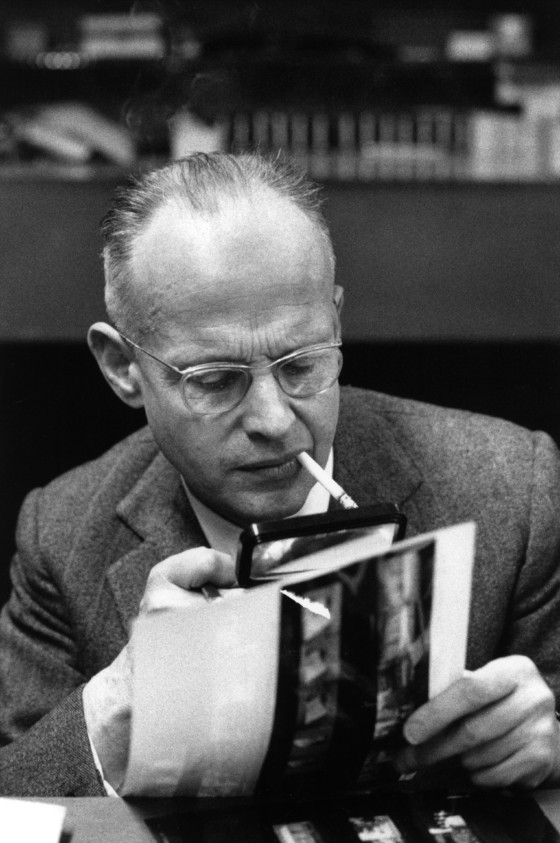

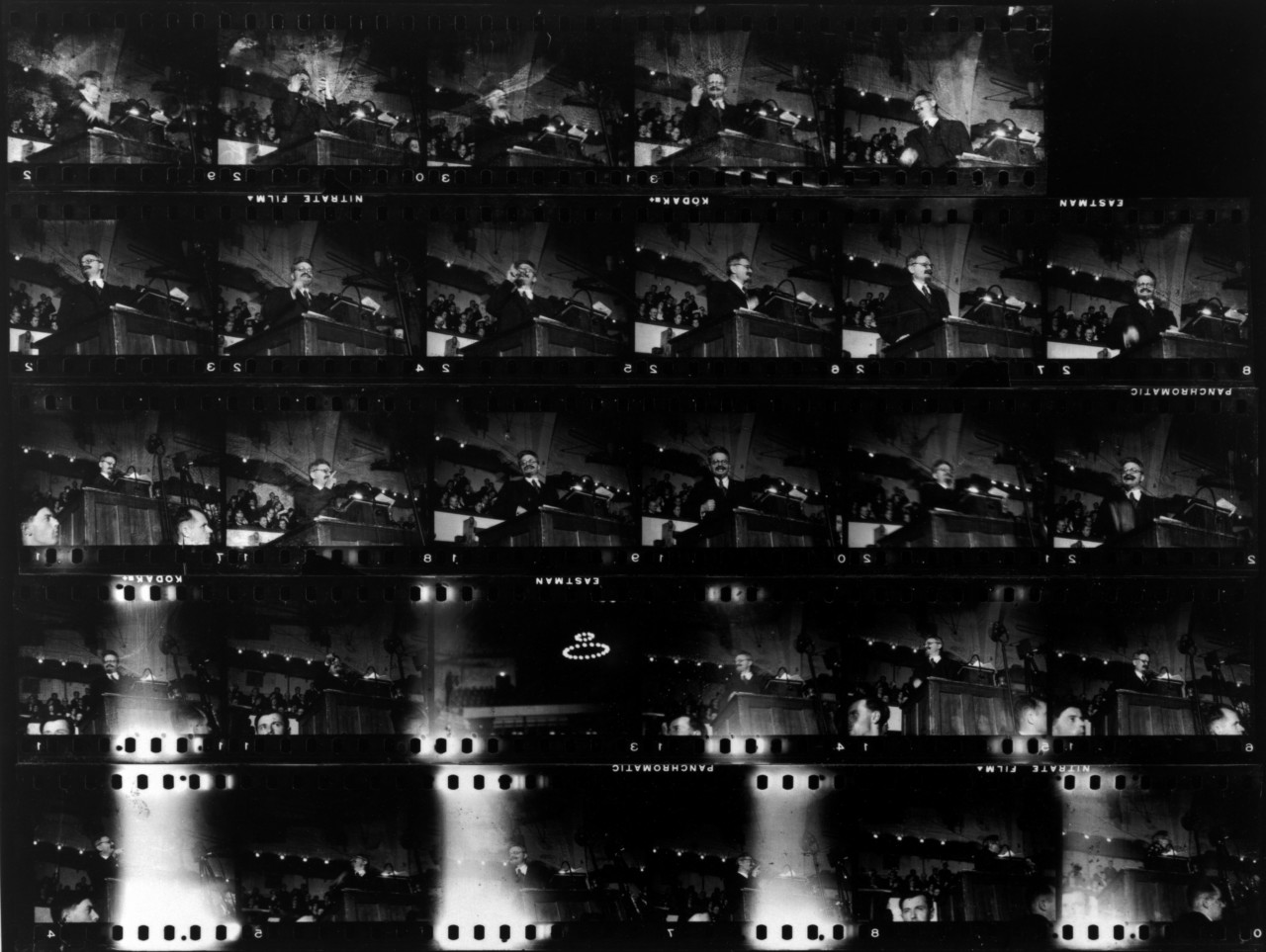

At LIFE, where I grew up, the photo editors would receive, for example, a sports story and then do a preliminary edit, and show that preliminary editing to an assistant managing editor who then would decide which stories could be used that week, so it was a complicated process. Even though I was quite young, I was privileged to work in the field with a photographer sometimes, actually shooting the story and often looking at the contact prints. In the beginning, at LIFE they didn’t bother with making contact prints; in the dark room, a choice of negatives would be made either by the photographer or by the lab person and enlargements would be given to the department managing editor. But then eventually picture editing became editing from contacts.

How is it best to approach doing an edit on a photographer’s work?

A sense of empathy, as with any other profession and taking a sincere interest in the story, understanding the story and understanding the motivation of the various people involved.

What kind of advice would you give to a photographer to help them to become better at editing their own work?

In journalism, one first looks for the meaning, the truth that’s involved in the image – does this image show something important? Is it true or false? The composition, the form, which is more of an aesthetic question, comes second. The ideal picture for a story first has to have meaning and secondly, hopefully, to have form – good composition. Good composition takes the eye to the focal point.

As someone who is anti-war, you’ve previously said that photography has had a role in that it helps people to understand the horrifying realities of war, in the hope, perhaps that people would be against war. But there are more horrific images of war in circulation than ever and yet war continues. Do you think people are desensitised to their effects?

You’ve raised a serious question: why is it, that after all these years of wars being photographed that we still have war? I’ve discussed this with Don McCullin: does our coverage of war tend to make heroes of soldiers? Is that the right thing to do? It’s sadly unfortunate that people have different reactions. A picture that may turn one person off, turns another person on. I, personally, think that pictures should be for real, they should be truthful.

What deserves to be photographed and what doesn’t?

I think now, there are too many photographs being made. It’s so easy to take a picture and to see it immediately. People don’t even think when they take a picture, they just go ‘bang, bang, bang’ and it’s not good. It would be much better if people took four pictures and concentrated on those few.

What do you think the role of photography is now?

I worry about it. I still see important pictures being made that represent the truth, and I worry that there’s too much concentration that will supposedly sell something. I don’t like to see photographers having to worry only about money.

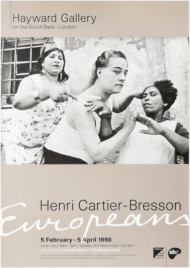

"I used to love to edit alongside Cartier-Bresson"

- John Morris

You’ve known Magnum from the very beginning, how do you recall that time?

I knew all the founders of Magnum, even before they knew each other. I met Robert Capa just when the war in Europe was starting. He had already covered the Spanish civil war. It was from Capa that I first heard of his dream of a picture agency. It was not called Magnum, it was just an idea that photographers should benefit more from the sale of their work. I called him my Hungarian brother, and I knew Robert Capa very well during the last 15 years of his life. I met him in 1930, he died in ‘54 on May 25. I became very close to Cornell Capa who was essential to the continuation of Magnum after his death. I also met Chim during the war, first in New York and then in Paris, where he wound up working in intelligence. He was not working as a photographer at that time. We became friends. Through Bob I met Cartier-Bresson in Paris; he was far from famous at that time but I absorbed a lot from him, particularly in terms of composition.

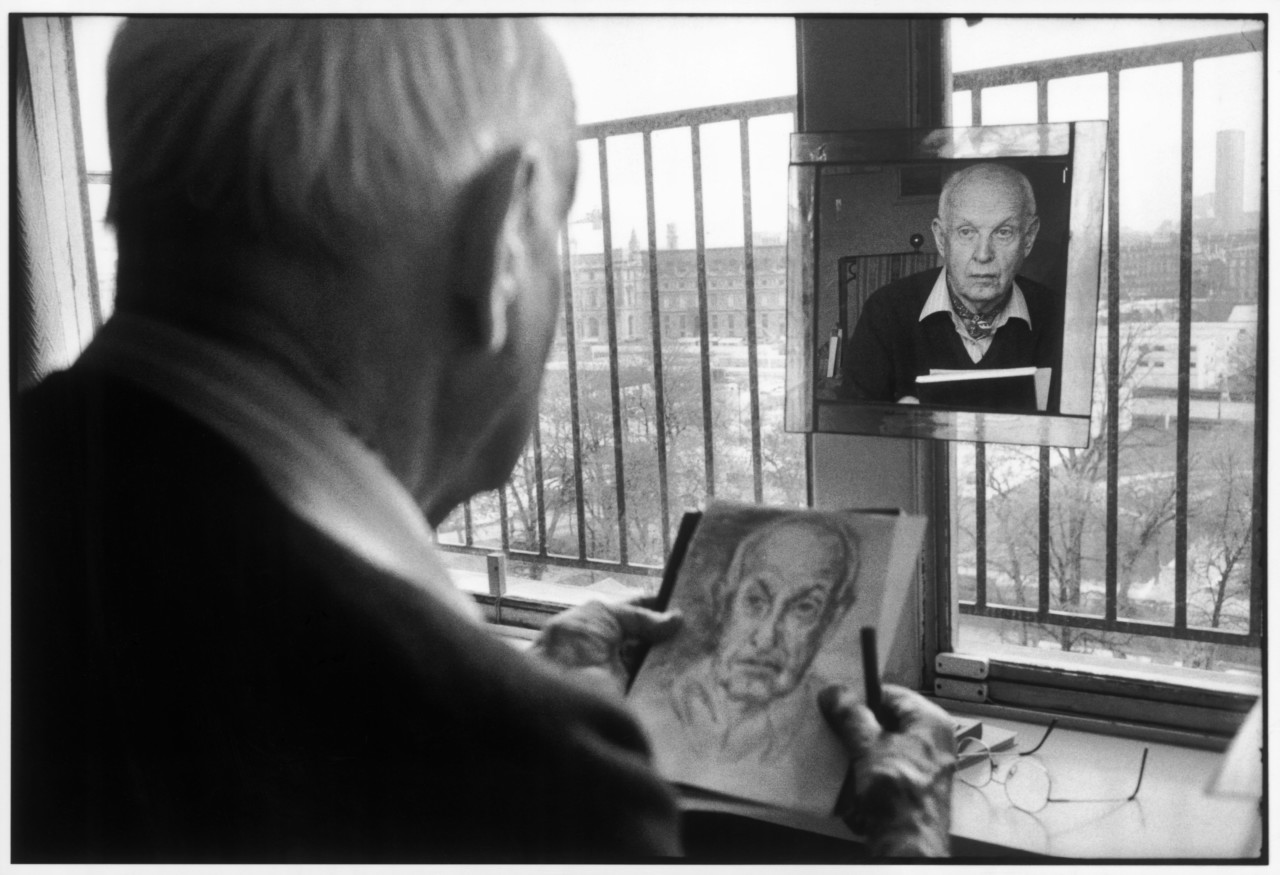

What did you learn from Cartier-Bresson?

I used to love to edit alongside Cartier-Bresson. In the early years, he never worked from contacts, but when he began working from contact sheets, often we would edit the same contacts and I would almost always end up picking the same negatives that he did. George Rodger was quite different. George was an adventurer, far more interested in travelling than he was photography. He was a good photographer but he was not a natural journalist, for example, sitting in our London office one day we heard a bomb explode and I said George go take a look and he came back with a beautiful picture of the victims of the Buzz bomb. It would never have occurred to George to go.

What conversations were they having back then about photography?

I don’t think they were interested in talking about photography per se, but the world. Photography was simply their way of expressing their concern about the world and what was going on. They didn’t talk about F-stops and exposures and what film they were using.