Learning From The Master

An exclusive extract from a new biography of Inge Morath explores her earliest days with Magnum, working in Spain under the at times gruelling tutelage of its co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson

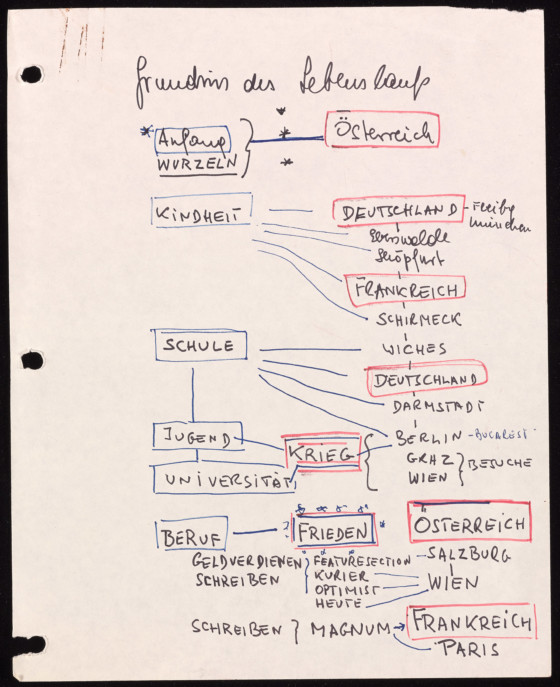

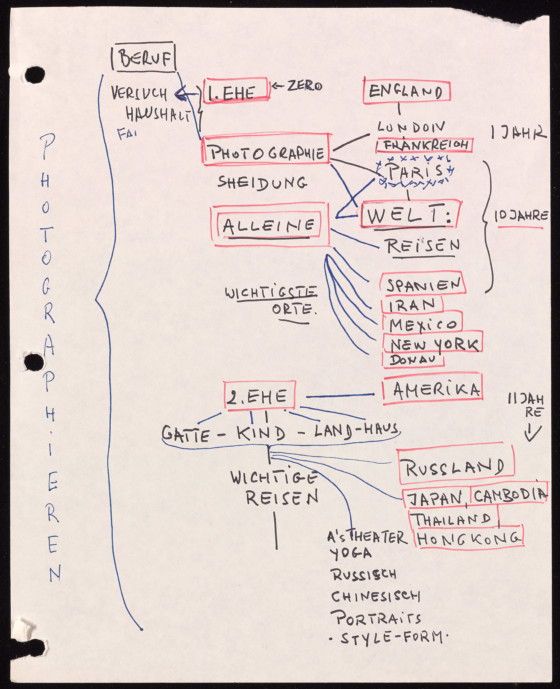

Austrian-born Magnum photographer Inge Morath (1923-2002) lived in Berlin during the war where, in the latter stages of the conflict, her university studies were curtailed when she was drafted to work in a factory making aircraft parts alongside Ukrainian prisoners of war. In 1945 Morath – making use of the chaos of an air raid – fled the factory determined to walk to Salzburg, 455 miles away, where her parents lived. It was a traumatic journey among fellow refugees and soldiers, which at one point drove her to the brink of suicide.

Morath reached Salzburg and found her family in time for the US-led liberation of the city. In her new hometown she took a job at the United States Information Service (USIS), translating articles and assigning photographers to them. Morath soon relocated, along with the USIS, to Vienna where she threw herself into the city’s artistic and intellectual scenes, before taking a new position as a journalist for Der Optimisist.

Her work for that title and her freelance writing led her to a position at the weekly Heute, where in her capacity commissioning photographers she met, supported, and championed Erich Lessing, and Ernest Haas among others. She and Haas struck up a working partnership and when Robert Capa invited Haas to Paris to discuss his work, in 1949, Haas took Morath with him. Morath entered the Magnum sphere as Haas’ professional partner, and was soon working with others in the collective. As Morath herself wrote in Inge Morath – Life As a Photographer, “I started to accompany different photographers on assignments for which I had also done the preparatory research, and later edited their contact sheets; I think that it is from this work that I learned the most.”

Magnum, at the time of Morath’s arrival, offered fertile ground for her growing love of photography. As is written in Inge Morath Fotografien 1952-1992, “Magnum, still a small agency, a group of enthusiastic photographers whose unbounded joie de vivre combines with the sense of mission of a generation who has lived through the madness of a world war, offers an ideal environment for Inge Morath’s development as a photographer.” All the same, her early months at the agency saw her at times rueing her subordinate role.

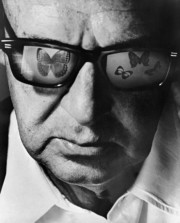

In 1953 Inge Morath was eventually assigned by Robert Capa to Henri Cartier-Bresson, as an apprentice and assistant. The pair’s relationship was formative to both Morath’s career, and her personal life. The two were lovers, intermittently, over nearly ten years prior to Morath’s marriage to the American playwright Arthur Miller, in 1962.

In this exclusive excerpt from the chapter Learning From the Master, taken from the new illustrated biography, Inge Morath : Magnum Legacy, by Linda Gordon [published by Prestel and Magnum Foundation], the pair’s earliest days working together are explored.

Extract

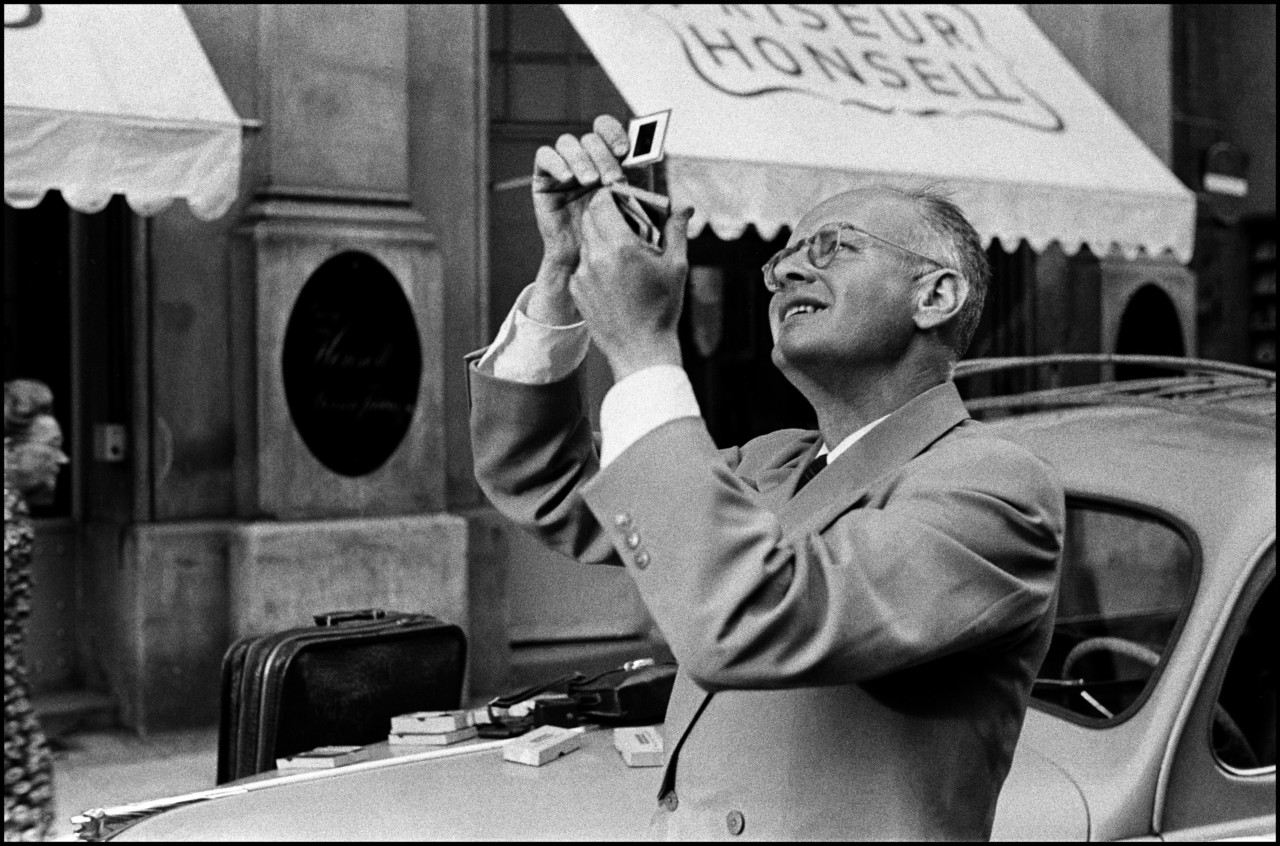

Cartier-Bresson was Magnum’s professor of photography. He taught Morath systematically, and she considered him “the hardest taskmaster.” Editing his contact sheets in her first years with Magnum had been an important part of this education, because doing so allowed her to examine the images in the sequence that he made them, to see his “rigorous pursuit of an event in clear geometric compositions.” Decades later, she summarized her process by writing, “I learned how to photograph myself before I ever took a camera into my hand.” She would practice “without a camera, with one eye closed and one open watching the street.”[i]Now Cartier-Bresson taught her to see composition by looking at photographs upside-down, a standard teaching method for photographers and painters. He gave her a Vidom viewfinder, which allowed the photographer to view her subject not only upside-down but also reversed right-to-left.[ii]He taught her economy and precision in defining her subjects and frames. He was not much interested in darkroom technique, and maintained a hardline rejection of cropping and other manipulation of the original image. For him, what mattered was finding the “simplicity of expression” at the moment of exposure. In one of many autobiographical texts written later, she quoted him as if from memory: “The recognition of a fact in a fraction of a second and the rigorous arrangement of the forms visually perceived which give to that fact expression and significance.” She was amazed at how fast he worked, yet remarked also on his patience in searching out the right location and waiting for the moment. “Now I had enough métier to absorb the essence” of his method, she wrote, learning “the conviction of composition, the constant alert, truth to the subject, ruthlessness when there was something to photograph.”

During their nine months of joint work, she traveled with Cartier-Bresson on several assignments.[iii]Holiday magazine wanted a photo story on “Europe,” so they took off in 1953, accompanied by Cartier-Bresson’s Javanese wife Elie and Holiday’s picture editor, Lou Mercier, driving through Germany, Italy, Spain, and England. Cartier-Bresson was demanding and when photographing, somewhat oblivious to others. He required Morath to carry the luggage, keep his cameras loaded with film, make notes for his captions. She had not yet learned to drive, so she sat in the back, waiting for him to stop when he saw something worth photographing. She spent evenings unspooling and cutting bulk film and loading it into cassettes, an activity performed blind with your arms inside a black bag.[iv]Doing such scut work cheerfully and uncomplainingly earned her some respect at Magnum, whose members registered her capacity for hard work as a mark of her determination.

————-

[i]Inge Morath, “I Trust My Eyes.”

[ii]Inge Morath, “I Trust My Eyes;” Russell Miller, Magnum: Fifty Years at the Front Line of History (New York: Grove Press, 1997), 103.

[iii]Elsewhere she wrote that her work with Cartier-Bresson went on for two years, Morath Papers, Beinecke Library, Box 585; and elsewhere she says a year and a half, in interview by Russell Miller, 10.

[iv]Inge Morath, interview by Russell Miller, 9.

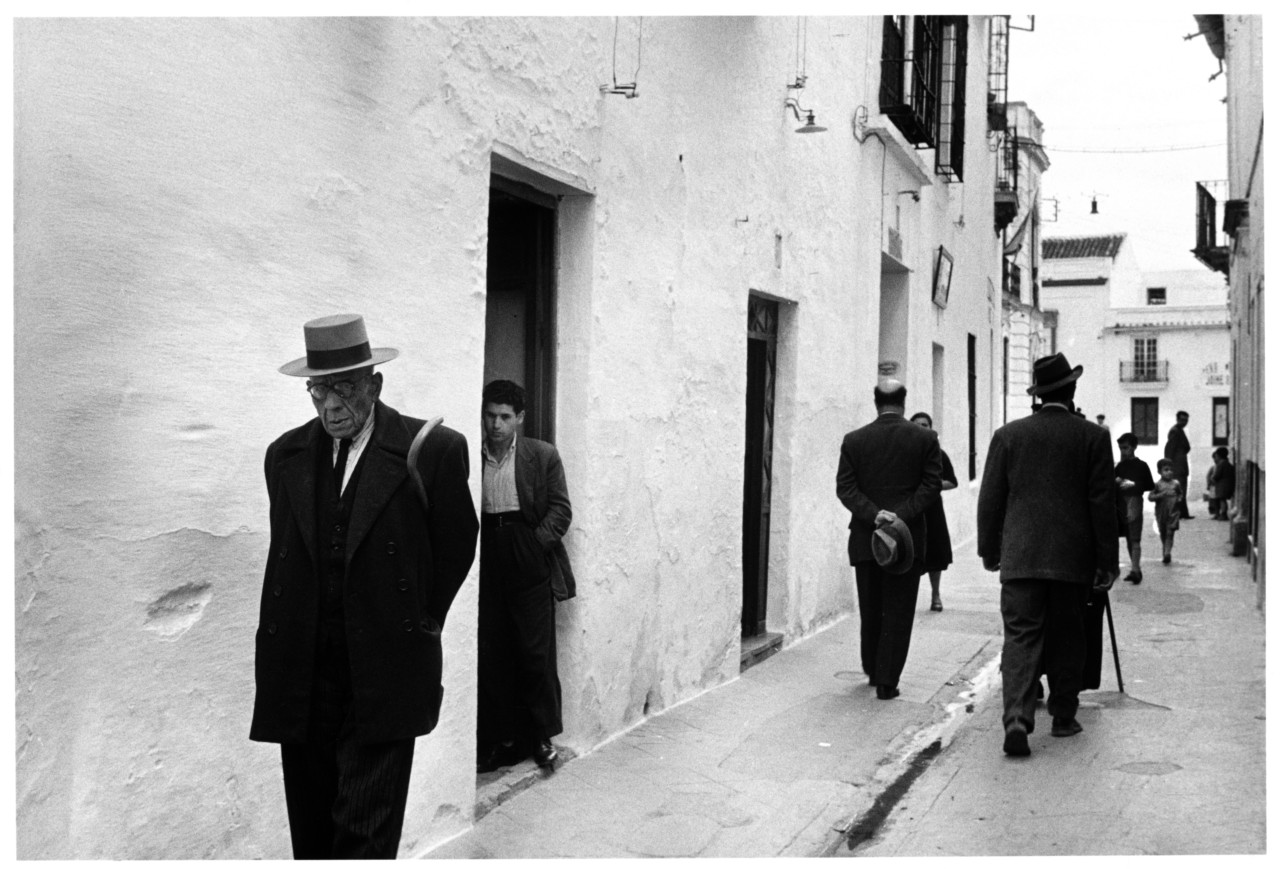

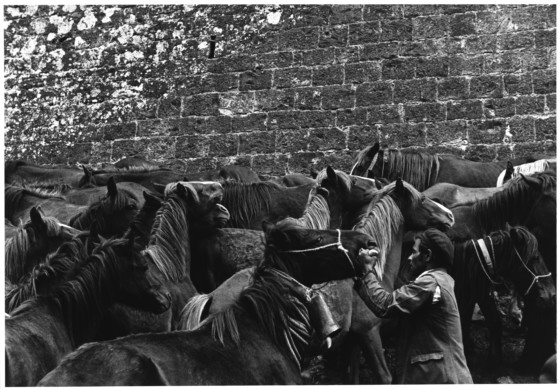

"The highlight of the Holiday piece was Spain, and Morath ever after felt a special connection to that country"

- Linda Gordon

Traveling with Cartier-Bresson limited her own photography, however, because “when you are with Henri it’s hard to photograph because he would see it first . . . and you can’t do the same thing . . . Nothing escaped his lens.” Still, she thought it was her “ballsy side” that evoked his respect for her—and attraction to her.[i]In her loving remembrance of this trip she recounted how they went into “every museum in sight” and discussed art passionately. (By contrast he hated to talk photography)

Capa’s decision to provide Morath with such a lengthy internship was simultaneously generous and also, possibly, sexist. None of the men were treated this way. Was admission to Magnum thus not only probationary but “premature,” requiring more training to get her to the right level? Or did Capa hesitate to send her out alone? (That would have been ludicrous given her previous experiences.) Whatever the reasons, Magnum was still unaccustomed to a woman photographer.

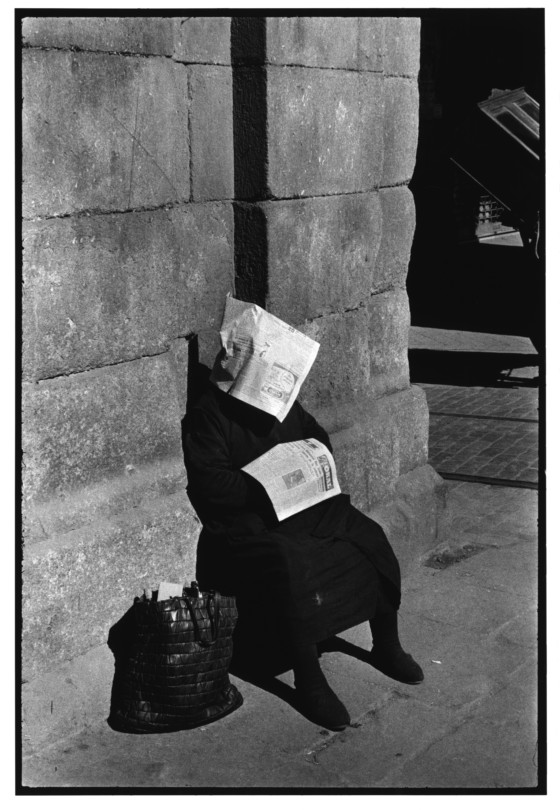

The highlight of the Holiday piece was Spain, and Morath ever after felt a special connection to that country. So Capa got her a Spanish project of her own, another Holiday feature, this one on “Women of the World.” He had identified the formidable Spanish feminist lawyer Mercedes Formica for one of the profiles.[ii]Before Morath left, he urged her to get better clothes—influenced perhaps by the fashion photography he had been doing.[iii]Her wardrobe apparently still consisted mainly of a black skirt with different blouses. Capa may have been trying to warn her about Spain’s conservative gender culture, and indeed, she met some difficulties in working as a woman there.[iv]

For that reason, beginning with Formica was a piece of luck, for she was respectable enough to introduce Morath to the right people and unconventional enough to like her. Born in 1913 to a wealthy family in Cádiz, Formica was an early member and leader of the Falange, a fascist party founded by Primo de Rivera, yet also an outspoken advocate for women’s rights. In the fascist Franco regime, she became notorious for defending a woman’s right to divorce and challenging the double standard regarding adultery. Morath may not have been surprised at this combination of fascism and feminism, given her mother’s support for the Third Reich and rejection of conventional gender standards; in any case, she did not comment on Formica’s politics. She spoke with respect of Formica’s integration of “emancipation and femininity,” as if a possible loss of femininity produced anxiety—hardly an unusual fear among women in the 1950s.

————-

[i]Inge Morath, interview by Russell Miller, 11; Inge Morath, Spanien in den Funfziger Jahren (Altzella, Germany: Batuz Foundation, 2000), 7.

[ii]Mercedes Formica-Corsi Hezode (her full name) was a prominent figure in Spain: editor of the weekly Medina starting in 1944, winner of the Fastenrath Prize from the Royal Spanish Academy. She felt nevertheless that her association with the Falangecost her some recognition.

[iii]Bernard Lebrun and Michel Lefebvre, Robert Capa: The Paris Years 1933-1954, trans. Nicholas Elliot(New York: Abrams, 2011), 238.

[iv]Inge Morath, interview by Russell Miller, 8.

"Over time, she made thousands of photographs in Spain, returning again and again, but even the earliest lot contained many stunning, beautifully composed images"

- Linda Gordon

Arriving in Madrid in 1954, Morath planned to follow Formica through her working days. Upon being admitted to the woman’s vast apartment in an exclusive Madrid neighborhood, where the maids wore uniforms and the fine furniture gleamed, she was nonplussed when Formica ignored her and continued signing papers while Morath moved around making photographs. She soon charmed her subject, however, with what an American friend called her “exquisite Old World manners”—a skill that helped her produce many celebrity portraits over the following decades.[i]Her most arresting photograph shows Formica standing on her balcony, the perspective evidently taken from an adjacent balcony. Though at home, the woman carries a small purse and wears a mantilla of lace covering a high pompadour hairdo. She stands at the far left of the image, her black dress and hair and long white earrings completing the vertical line of the building’s wall, while two-thirds of the photo shows a Madrid street scene. The composition, combined with Formica’s elegance, beauty, and downward gaze onto the street below, accentuates her upper-class standing and her exclusive neighborhood.

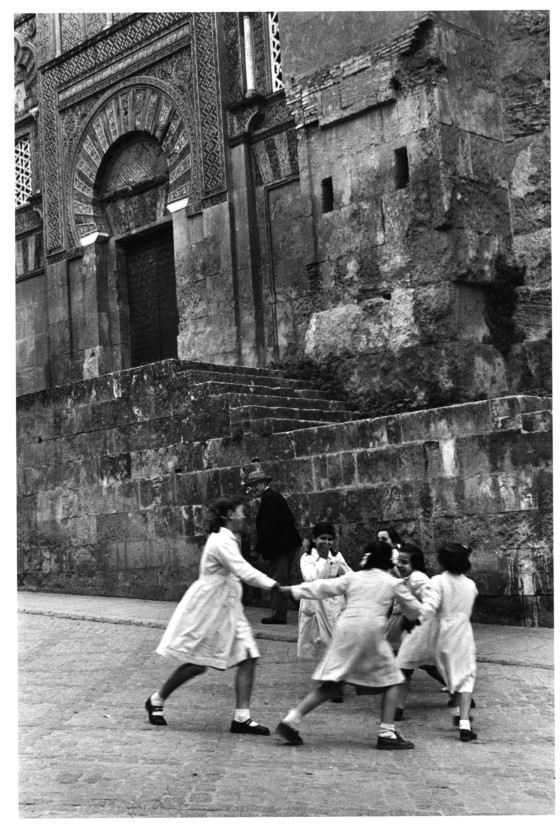

Spain promised superb photographic opportunities, so with Magnum’s permission and a loan from her brother, Morath extended her stay for three more weeks. She was in love with the country. Over time, she made thousands of photographs in Spain, returning again and again, but even the earliest lot contained many stunning, beautifully composed images. In Cartier-Bresson she had the greatest of teachers, and she was a pupil who not only absorbed lessons, but soon developed her own style and mastery.

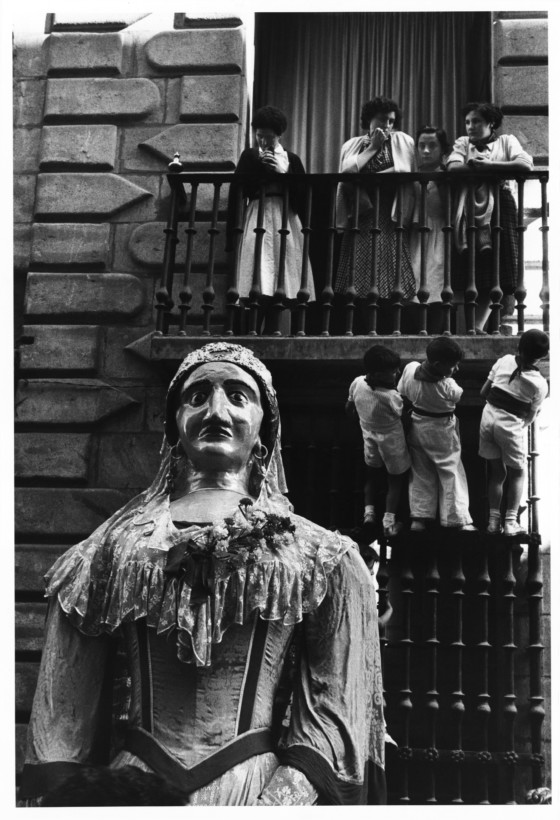

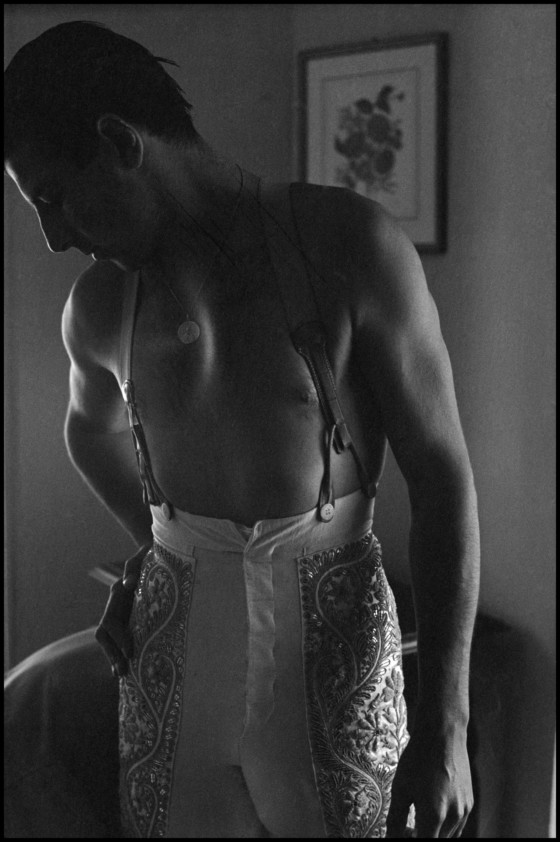

Morath delighted in Spain’s vivid folk and religious rituals. Formica was being honored by a falla, a festive event in which a papier-mâché effigy of the honoree is erected and then, after a few days, burned under a canopy of fireworks. (For this particular festival, Dalí had made one of the falles.)Through Formica she met Gonzalo Figueroa, the Duke of la Torres, who was almost immediately infatuated with Morath—one of many doors that Formica opened for her. Insisting that her plan to travel around Spain by herself was simply impossible, he offered to drive her. He began the trip as he always traveled, with two Cadillacs, one for him, his valet, and secretary, the second one with a library from which his secretary read aloud to him, as he was blind in one eye. When he understood that she wanted to go into the countryside, he switched the Cadillacs for a Land Rover.[ii]Morath’s beauty and graciousness proved useful in creating photographic opportunities for her.

————-

[i]Olga Andreyev Carlisle, in “Instantaneous Forever,” in Inge Morath, Russian Journal 1965-1990 (New York: Aperture, 1991), 119.

[ii]Inge Morath, Spanien in den Funfziger Jahren (Altzella, Germany: Batuz Foundation, 2000) 12–13.

"Lola and her three grown children were drinking and smoking, playing piano and guitar, with a massive Picasso oil of a First Communion in the background"

- Linda Gordon

Back in Madrid, Formica hosted a party that proved to be lucky for Morath. An elegant Spanish man, to whom she had not yet been introduced, asked her what she thought of the clothing of the fashionable women in attendance; she replied that while she admired the styles on display, she would stick to her black skirt until she could afford “something really great.” The man turned out to be legendary fashion designer Cristóbal Balenciaga, and he invited Inge to his atelier, where he gave her two suits and a grey dress. Her height and slim build no doubt made her the perfect model for his clothes. When she returned to Paris, she found it delicious to show off her new clothes to Capa. “It was great to see his face,” she wrote, “when I showed up in my first Balenciaga.” She would wear Balenciaga clothes whenever possible for the rest of her life.

She soon received another Spanish commission from the French art magazine L’Oeil—to photograph Picasso’s sister at home with some of his early paintings. When she arrived for the shoot at the appointed time, midnight (Spaniards eat supper very late), Lola and her three grown children were drinking and smoking, playing piano and guitar, with a massive Picasso oil of a First Communion in the background.[i]Some of the photographs she made there are like family snapshots, homey, except for one portrait of Lola Ruiz Vilato herself, with the strong facial features we recognize from images of her brother.[ii]The family’s lack of reverence for the Picasso art they lived with appears in one of these images: a Picasso drawing hanging somewhat casually on a wall, under a broken glass frame, with a little cartoon inserted into a bottom corner of the frame, underneath a large black-veiled marble sculpted head of the Virgin—probably mass-produced—which someone had crowned with a halo of artificial flowers. More Picasso paintings lay on the floor. Morath evidently enjoyed this nonchalance toward great art.

————-

[i]Ibid., 20.

[ii]When Ruiz Vilato asked “how do you want me to look?” Morath answered “As you would look at Pablo.” Ibid.,20. Critic Sabine Folie calls the images labeled “family snapshots,” “mysterious genre” pictures because of their unsettled feeling, as people change places around the small room. Sabine Folie, “Inge Morath: A Visual Historiographer,” in Inge Morath: Life as a Photographer (Vienna: Kunsthalle Wien; Munich: Gina Kehayoff Verlag, 1999), 29.