The Language of Pictures: Exploring Sequencing With Mark Power

The Magnum photographer teamed up with Stuart Smith, director of Gost Books, to seek a new visual approach to 21 years of his archive

“Anybody who has ever tried to arrange a bunch of flowers, to shuffle and shift the colours, to add a little here and take away there, has experienced this strange sensation of balancing forms and colours without being able to tell exactly what kind of harmony it is she is trying to achieve. We just feel– a patch of red here may make all the difference, or this blue is all right by itself but it does not ‘go’ with the others, and suddenly a little stem of green leaves may seem to make it come ‘right’. ‘Don’t touch it any more,’ we exclaim, ‘now it is perfect.’ Not everybody, I admit, is quite so careful over the arrangement of flowers, but nearly everybody has something she wants to get ‘right’.”

Excerpt from Ernest Gombrich’s, The Story of Art.

Last month in Lisbon, Magnum Photos collaborated with BCG Henderson Institute to organise a five day Live Lab on book editing that presented the creative process of making a new body of work within the context of a conference, the House of Beautiful Business, whose programme explored man’s relationship to technology.

Magnum photographer Mark Power and director of Gost Books, Stuart Smith, worked through Power’s archive of twenty-one years of photographs made on construction sites and in factories, reassessing the work and producing a new narrative for potential publication. Power is vocal about the importance of his commissioned work in general, how it sits comfortably alongside his self-generated work, and specifically about its use as material for this project, “I felt it should be a celebration of the work I’d made, all on commission, to show that it’s possible to make your own work under such circumstances. Just because I was getting paid for doing it didn’t mean I took it less seriously, or made less valid work. I believe this very strongly.”

This project was conceived as a practical demonstration of the collaborative creativity between Power and Smith as they worked to meet this specific challenge. It also used the methodology of book editing to explore the bigger question of why we select certain images over others, and the means by which we sequence photographs to build narrative.

The Lab itself was structured around the architecture of the conference and the book making process. Further historical context was provided by Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Man and Machine, a book project that resulted from a commission by IBM in 1967 for the photographer to explore human relationships with technology around the world. At its heart were three days themed to reflect the different tasks of the editing process: Editing, Sequencing and Narrative. The work in the Lab followed this structure and alongside the Lab, short experimental workshops were held for conference participants, under the guidance of Smith and Power, to engage with these same tasks applied to a pool of ‘man and technology’ themed images from Magnum’s archive.

Power’s interest in documenting man made environments began in 1996 with his project on the construction of the Millennium Dome. First viewing it on a one-day assignment, he subsequently gained access to the site, by persuading the company behind the project of the Nineteenth Century standard of photographing large scale public buildings ”I was making the point that back then it was normal practice for a single photographer to follow the process of a build from beginning to end. In fact, some of the most sought after photobooks are these very albums… often printed in editions as small as ten or twelve, with copies given to the architect, the builder, the mayor”. The subsequent book of Power’s work on the Dome, ‘Superstructure’, was to be the first in a long collaboration with Stuart Smith, a well-respected book editor and publisher who, having worked for many years as a book designer, set up his own company Gost Books, in 2013 to produce and publish artists books.

Of his relationship with Smith, Power says: “Although we’d worked together before on my book edits he’d be the first to acknowledge that I’m usually pretty tricky to deal with. I tend to arrive at his office with a tight edit because I’ve usually been working on a very specific subject over many years, and throughout that period I’d be constantly re-editing and re-sequencing the work”. Prior to Lisbon, Power had in fact tried to create his own edit of work on the built environment but found the task “overwhelming and, ultimately, hopeless. I was simply using all my big-hitting pictures… So, in Lisbon, I was willing to ‘let go’, and pass much of the editing over to Stu.”

As Smith says of the Live Lab, “The House of Beautiful Business was the catalyst in terms of the theme of Man and Machine and fitted in with all the work that Mark had done, [it] gave us the opportunity to spend 3 to 4 days in a room without interruptions from our normal everyday work, it was an intense time where we worked from 7 in the morning to 7 or 8 at night, and this environment enabled us to concentrate in this unique way.”

Of his approach to the theme Power explains: “I’m less interested in the literal relationship between man and machine [as explored by Cartier-Bresson] but instead I’m more concerned with human achievement. I guess I want to celebrate the beauty and wonder of making things.” He and Smith had already chosen the title ‘Fashion’ for the book prior to Lisbon, referencing the hand made nature of the subject.

Commencing the edit of this group of images, made with a singular vision, but sourced from a number of different locations and projects, Smith describes the process “like pick up- sticks, I need to look at everything first to think about what the book might be”. This visually led approach de-emphasised Power’s attachment, as the author, to the photographs context and thus freed the work up for experimentation. On day one in the Lab, the pair began by looking at over 4,000 pictures to get to an edit of 600 prints, from which 196 were finally selected. During this process the pair began by making piles based on themes. Power says of the collaboration: “Stu encouraged me to bring in pictures that weren’t necessarily my ‘favourites’, and of course he was right. You can’t have a relentless sequence of ‘big pictures’. There have to be moments of quiet as well.”

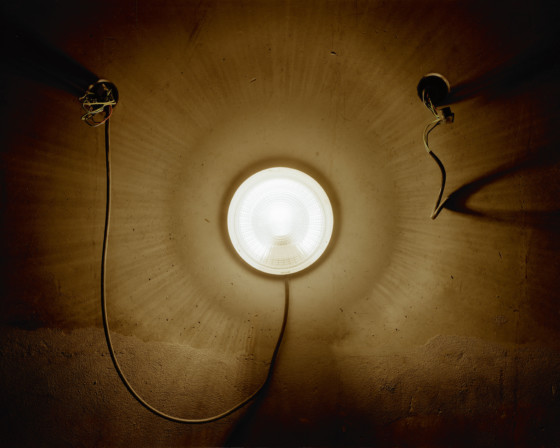

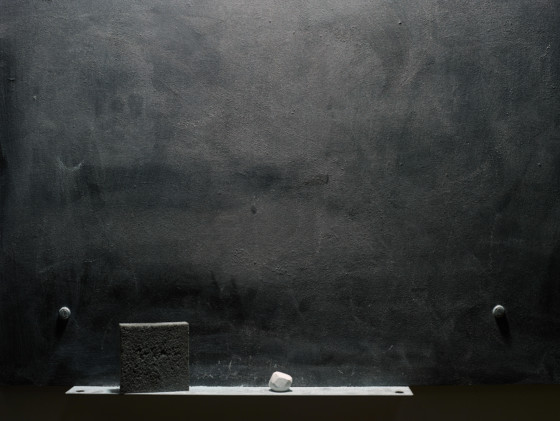

On Day Two in the Lab Power and Smith began sequencing, in which pairs or triptychs of images took shape. Of the particular magic of these visual relationships Power says: “Photographs are a fantastically complex visual language all to themselves, but you have to be careful: pairing two pictures you might be sure would work together often don’t; for whatever reason they might cancel each other out. On the other hand two pictures that might not individually be so remarkable can each lift the other to be much better… and suggest a sort of ‘third thing’ floating somewhere between the two.” As they worked, the Lab exploded in a riot of photographs, as prints were laid out on the floor and walls of the space, the pair both in socked feet, arranging and rearranging combinations in a physical demonstration of their thinking through this complex visual puzzle.

The final day with its focus on narrative saw the book begin to take shape. As Power explains: “John Gossage, the great American bookmaker, once said that it was impossible to sequence more than six or seven pictures before you have to start all over again. There’s a lot of truth in this, but we tried to increase that to nine or ten, in 16 page sections, each with a beginning and an end. Essentially we were sequencing visually, but we both wanted to veer away, as best we could, from simply sequencing because of similar colours, or repetitious shapes. If we could incorporate subject, irony, colour and form then we were onto something.”

The nature of this storytelling process is unique to the chemistry between the participants. As Power says “The important thing to remember is that there isn’t just one correct way of sequencing pictures. There are many, and it’s very subjective.” This potential variety of routes through material was also highlighted in the workshops run alongside of the Lab during which participants, in a very short window of time, instinctively found diverse ways of building a story with Magnum images – by theme, by using pictures to illustrate a preconceived narrative, by form, texture, colour or mood.

The prints in both the Lab and workshop presentations were uncaptioned, and it is notable that Smith and Power have been consistent in their layout for the book in maintaining this decontextualized narrative in their non-linear, non-chronological sequences. As Power says: “we don’t want captions describing where each picture was made, either underneath each image or even at the back. The other extreme would be to reveal absolutely nothing, but we think a good compromise would be to list, somewhere in the book, a set of locations without being specific about which is where. Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel did this in their seminal book, Evidence, which is an important touchstone for us”.

Of his time in the Lab Power says “it was wonderful to have Stu’s undivided attention for three whole days. We’re normally both too busy for that to happen. It demonstrated how much it’s possible to achieve if you switch off from everything else and give total concentration to just one thing”

Power’s photographs delight in man made forms, their structure and detail rendered beautiful in the play of texture, colour and light. In the current draft of ‘Fashion’, Smith and Power have created sequences of nuance and subtlety, whose juxtapositions are witty, playful and imbued with a sense of the uncanny. The book’s narrative remains purposely inconclusive – the project, like the lab itself, a photographic journey through process, giving space within its architecture to accident and experimentation, and in doing so demonstrating the essential human joy of making things.