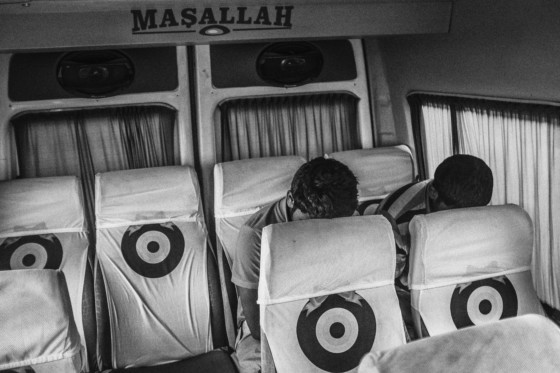

My Turning Point: Emin Özmen in His Own Words

The Magnum Nominee on how documenting unrest in his home country of Turkey was the motivation for his photojournalism career

Emin Özmen joined Magnum as a nominee in Summer 2017. Here, in his own words, the photojournalist explains what drove him to pick up his camera, and why those stories closest to home hit the hardest.

I was in my early twenties when I decided to continue my life as a photographer, documenting social life and witnessing history around the world. I wanted to discover and understand my country and its people.

I documented the Tohuku earthquake in Japan in 2011, and after that, I worked on the economic crises in my neighbour country Greece. That same year I spent some months in East Africa, covering the famine in Somalia and Kenya. I was working for one of the biggest daily newspapers in Turkey; it was the turning point for me, I was able to bring attention to these important crises from my home country.

During my reporting, my company organized a campaign in collaboration with Turkey’s Red Crescent, which became the biggest aid campaign in Turkish history. 450 million TL was collected with the help of Turkish community; hundreds of ships and planes carried emergency aid and I continued to document the changes in East Africa for some years. It was the first time I witnessed the power of photography and journalism.

In 2011, when the civilian conflict started in Syria, I felt the war come home. It was one hour away by plane from my house in Istanbul. I was uncomfortable in my home with this big tragedy happening so close to me. With this as motivation, in 2012, I crossed the Turkish Syrian border to witness and document it. I found myself deep in this bloody war: day and night operations, interrogations, torture.

On my last border crossing I witnessed public executions, in August 2013 in northern Aleppo. This work was published in leading media titles with anonymous credits. After this, I was not the same person anymore; I spent some months psychologically down, not able to work or photograph anything.

During this period, the Gezi Park occupation – the biggest protests of Turkish history – took place in Taksim, the heart of Istanbul. It was the result of long-term polarisation in the Turkish community. Turkish by birth but not Kurdish, I grew up in a culture where the Kurdish issue is ever-present. For years, I have tried try to understand this complex issue, which to date remains sensitive.

I started to document the Kurdish issue in Turkey during the fight between Kurds and ISIS militants in Kobani in 2014, but for Kurds in Turkey, everything definitively changed on June 7, 2015, during the general elections. Hope finally emerged from the polls: the pro-Kurdish party HDP won 13% of votes and at the same time deprived President Erdogan of his party’s hold on Parliament. Expectations were very high, as was disillusionment the next day.

Turkey had seen its old demons resurface. The sound of the bombs was again heard in Suruç, Diyarbakir, Ankara, and in the Southeast, in mainly Kurdish places. The fragile cease-fire achieved in 2013 between the AKP and Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) had been shattered. Again, Kurdish civilians found themselves hostages of a 30-year-old conflict that had already taken the lives of over 40,000 people.

To overcome the PKK and their youth branch, YDG-H and YPS, all deeply established in populated urban areas, the authorities did not skimp on the means. Dozens of local elected officials, suspected of supporting terrorism were arrested or laid off. One by one, the Kurdish cities were placed under curfew: 7 cities and 22 districts affected, tens of thousands of people forced to live holed up at home. More than 350,000 people internally displaced according to Turkey’s Human Rights Foundation.

Then, Turkey witnessed the bloodiest coup attempt in its political history on July 15, 2016, when a section of the Turkish military launched a coordinated operation in several major cities to topple the government and unseat President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Soldiers and tanks took to the streets and a number of explosions rang out in Ankara and Istanbul. 265 people died, including soldiers, police and civilians. The day after, the government announced a state of emergency and more than 100,000 government employees – civil servants, military personnel, police officers and teachers – were sacked for their alleged association with the Pennsylvania-based preacher Fethullah Gulen.

Many Turks refer to Gulen and his followers as the Fethullah Gulen Terror Organization (FETO) and accuse them of leading last year’s coup attempt. Nearly 50,000 people remain in jail pending trial. Several thousand politicians with the predominantly Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party are among them.

Since the beginning of the Syrian civil war, all the dynamics have changed in border countries, especially Turkey, a country moving slowly towards real democracy. Political tension is at the highest level in modern Turkey’s history. Journalism is more important than ever.

Unfortunately, we – all the journalists and photojournalists – continue to work under heavy pressure in Turkey. We have the responsibility to document all of these issues, we have to ask questions and try to find answers. But today, journalists, those trying to shine a light on the darkness, are the main target. More than 150 journalists have been jailed in Turkey since the bloody coup attempt in 2016.

People always ask me if I am afraid. I’m not afraid because I strongly believe that what I am doing is the right thing in the name of journalism and truth – for history. But honestly, I always feel tension while I see many of my friends and colleagues going to jail or being deported just because they do their job. But I feel stronger when I remember the lyrics of the great Turkish poet Nazım Hikmet:

“If I don’t burn

if you don’t burn

if we don’t burn

how will darkness

ever turn

into light?”