In the Balkans: States of Transit and Transition

30 years after the fall of the Iron Curtain, Nikos Economopoulos discusses the paradoxes and complexities of the Balkans and the work he made there

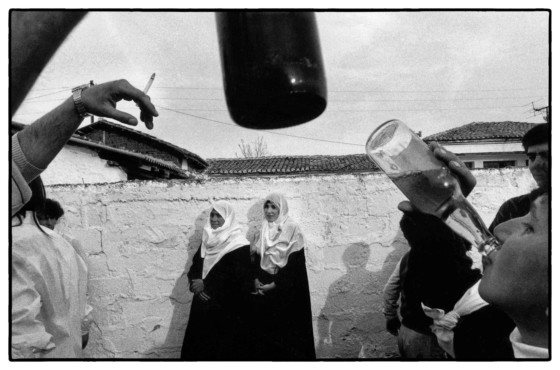

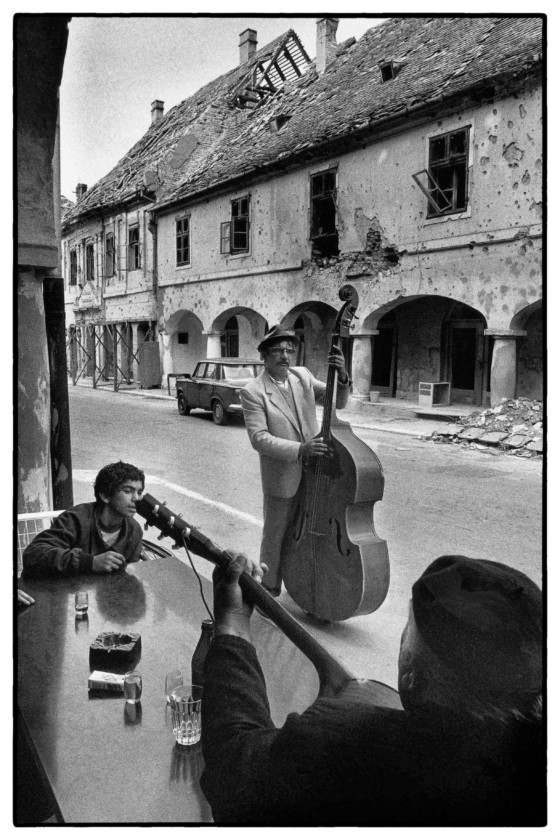

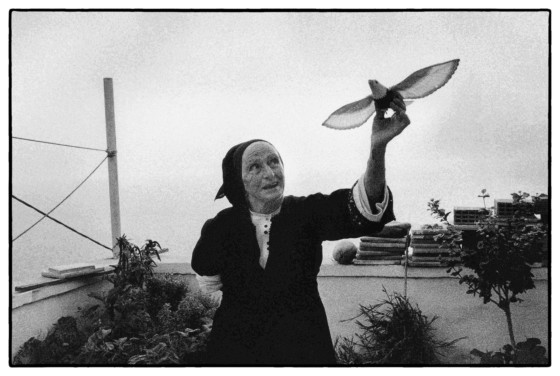

Many in the West look back on the fall of communism and immediately think of the fall of the Berlin Wall, recalling vivid snapshots of emotional celebrations among the masses who gathered in that city, the joy in the faces portrayed on TV screens and newspapers. Instead of turning his attention to the events unfurling in Germany, Greek photographer Nikos Economopoulos turned his gaze toward the less-explored aspects of the story: the fall of communist regimes in Albania, Bulgaria, and Romania, the concurrent financial crisis in Turkey, the lives of minorities in Greece, and growing tensions in the former Yugoslavia. The work he produced in the region between 1987 and 1995 became the book, In the Balkans (also published in Turkish as Balklanlarda).

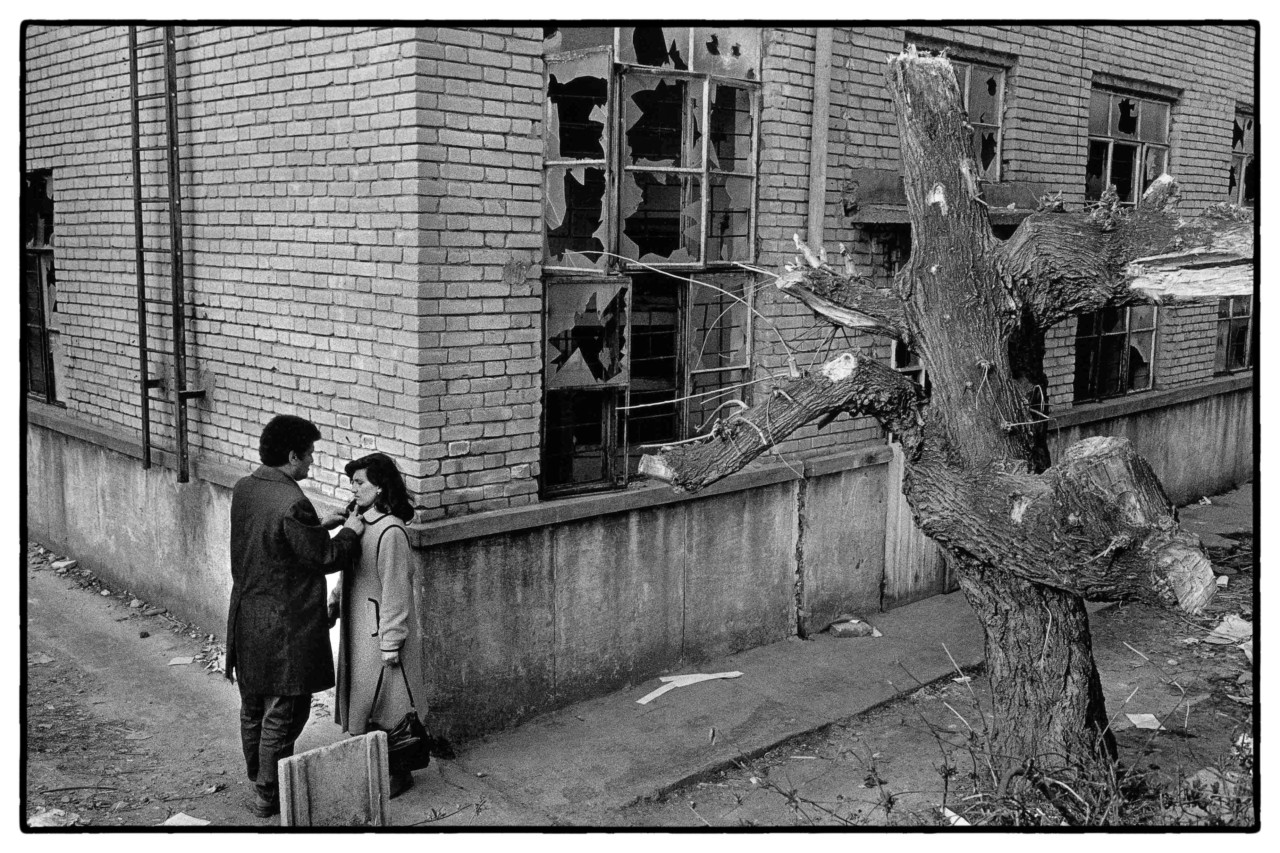

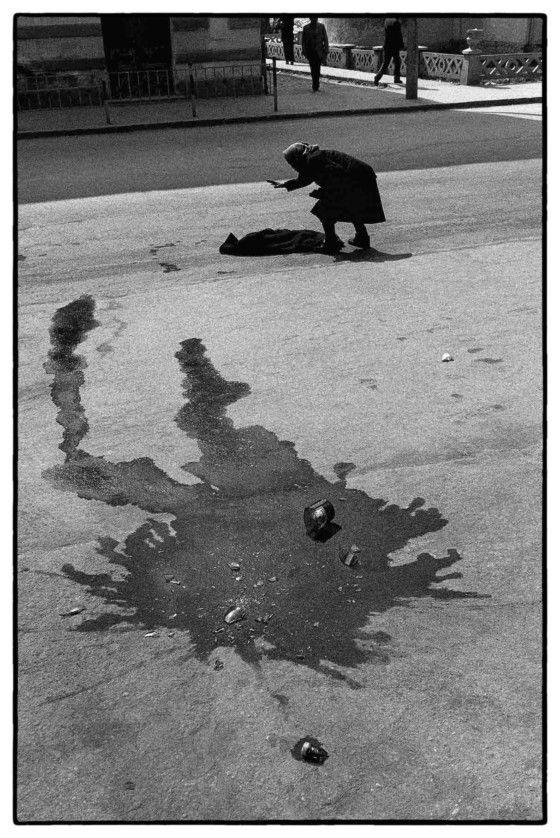

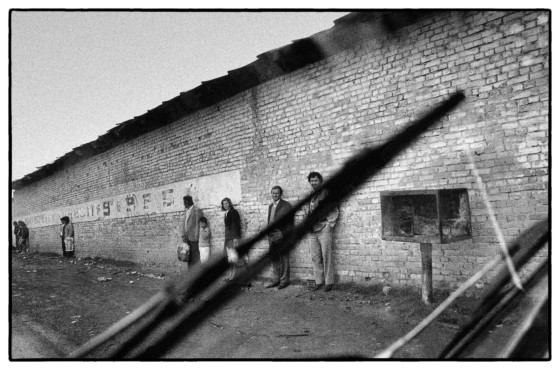

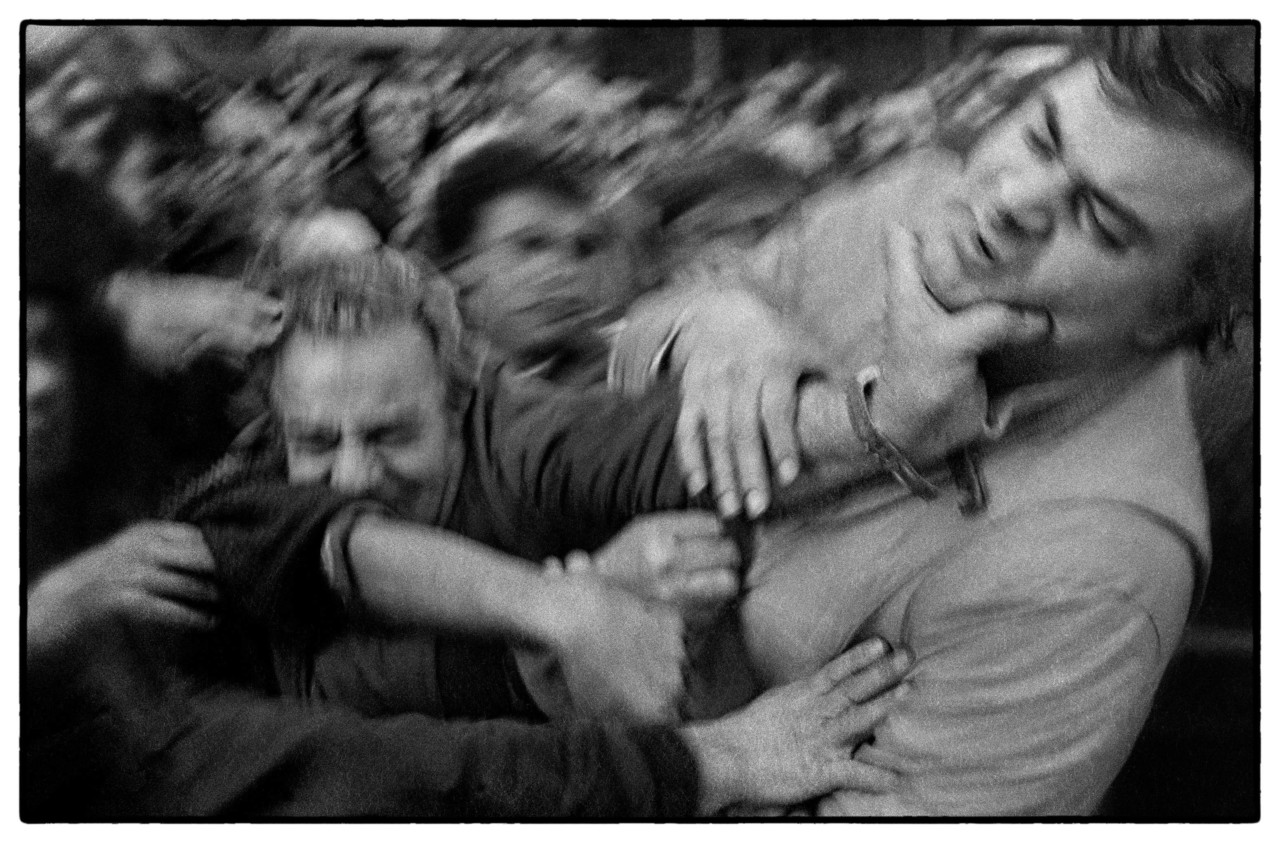

Various communities in the Balkan peninsula shared the impacts of a broad-scale redefinition of the geopolitical map, the burdensome transition to free-market economies, and war throughout the late 80s and 90s. While Greece had become a full member of the European Union by 1981, the other new-born or transitioning countries were aspiring to catch up with the West. Many Balkan states faced a stark post-communist reality: the privatisation of utilities and state-owned factories, and simmering resentments over unresolved crimes committed by communist regimes – all of which resulted in harsh socio-economic conditions and politically divisive landscapes. In the midst of an uprising in Turkey, the war in Yugoslavia and the assassination of the communist leader Nicolae Ceaușescu in Romania, many personal stories might have been lost. Economopolous attempted to suspend that loss by documenting lives in the region.

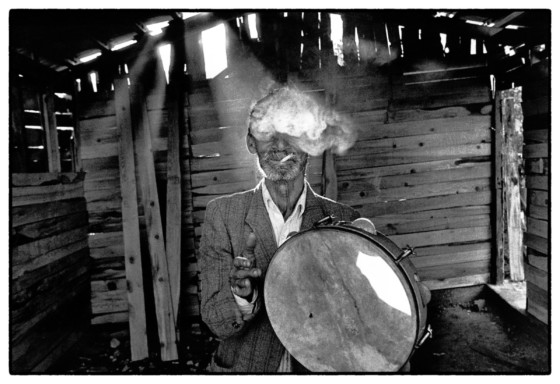

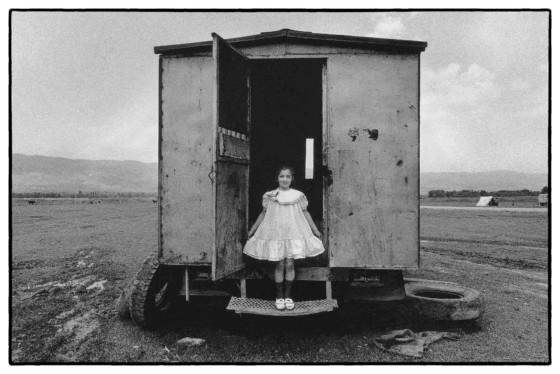

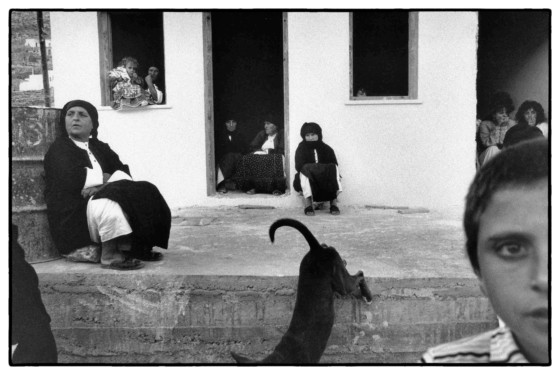

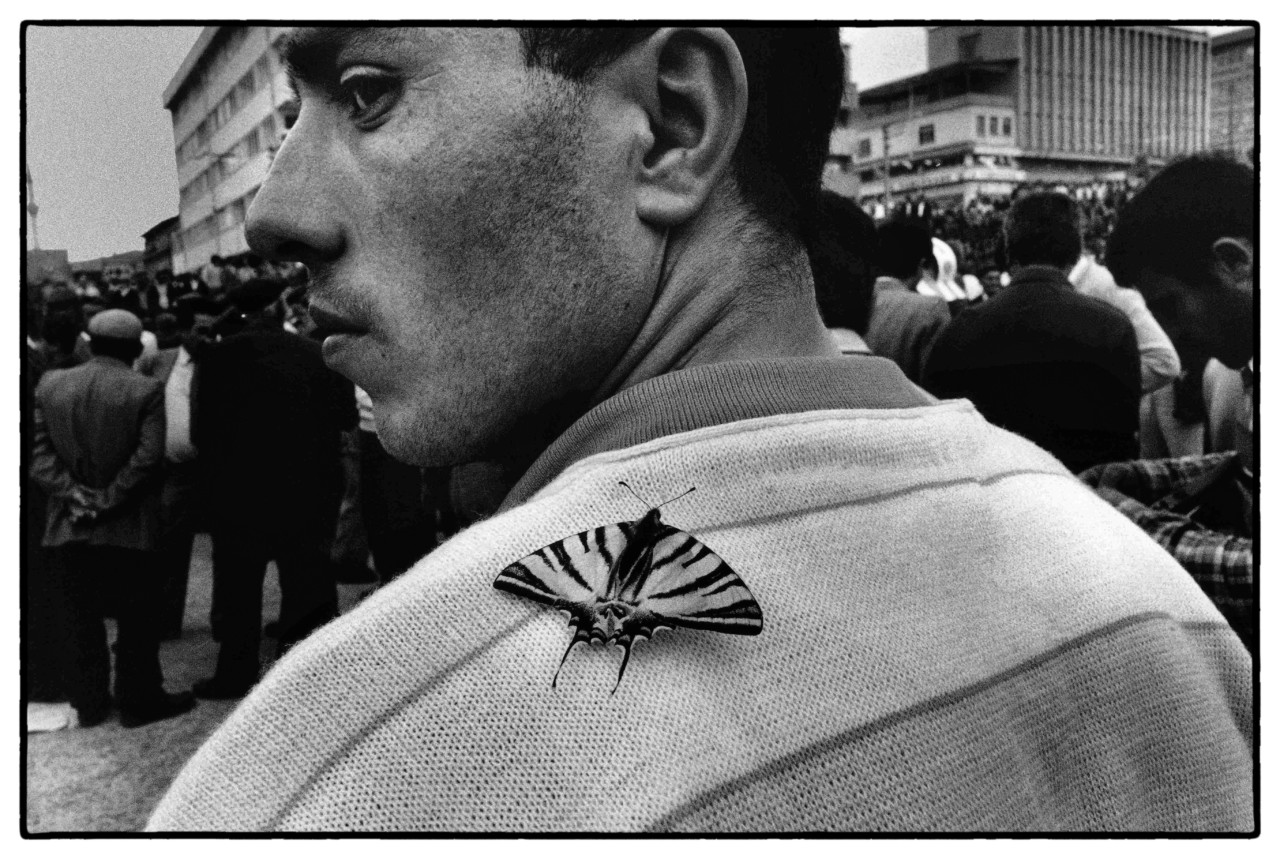

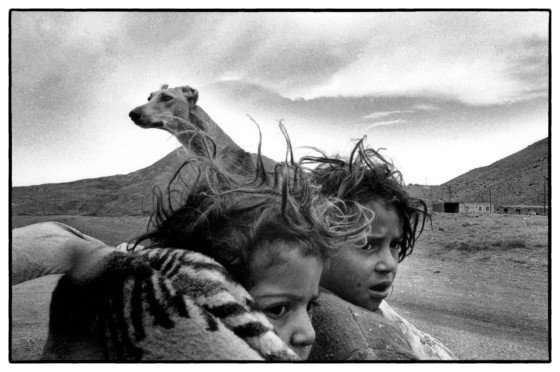

Economopoulos presents the region as a fragmented and multidimensional story. As he noted in the book’s foreword – the name of the region is itself a contradictory combination of the Turkish words for honey and blood: “bal” and ”kan”. In the Balkans explores the paradoxes of the region: it depicts similarities between people and tensions between nations in this area of the world that straddles the borderlands between Asia and Europe. Economopoulos explores the possibility of new beginnings that follow the coexistence of war and peace, celebration and slaughter, intimacy and hatred. He calls attention to marginalized communities, the Romani and Pomak, living throughout the peninsula. The latter section of In the Balkans explores how life for some became mired in poverty during the failure of various welfare states and the consequent economic crises that engulfed the region.

Here, 30 years after the fall of the Iron Curtain, Economopoulos looks back at In the Balkans.

Leafing through In the Balkans, one feels a clear sense of loss, disillusionment and displacement. On the other hand, people from across the Balkans can likely identify with these images, they may feel familiar to them. Can you talk a bit about this notion of the Balkans as a place where similarities and fragmentation between peoples coexists?

This is the Balkan paradox, the ground on which they stand, the fundamental contradiction that shapes the history of this place. Warmth, expressiveness, heartfelt hospitality, comradery, community spirit – these are things you can identify with. And yet, at the blink of an eye, the same emotions are overturned and are replaced by hostility, divisiveness, hatred, fury – things you cannot control or comprehend. It is as if it’s a place that enables and nurtures both. Roaming around this territory is an exercise in seeking familiarity and at the same time navigating deep waters.

That’s what the Balkans are for me: a modest abode that shelters light and shadows and stark darkness altogether in an explosive mix. It is what the name indicates: the blood and the honey.

This is a situation that cannot be explained with rationalism, or the tools of the Enlightenment. The only way to approach it is through instinct: the survival instinct of entire communities which have had to struggle in order to subsist on the edge of – and yet so close to the heart of – Europe. In societies where rules and functional centralized institutions are not in place to provide the tools for coexistence, people retreat back to instinct in order to handle the chaos around them – often expanding that chaos more. This absence of rules stretches and accentuates the emotions. For bad, for worse – yet, also, for good.

All the negative stereotypes associated with the Balkans somehow contain their inverse. There is a strange sense of pride that entails profound attachment and affection, which at the same time can turn against itself. Things that reason deems incomprehensible. Ultimately this interests me more than the narratives which can fit into neatly organized boxes. You have to step out of your own box to even begin to comprehend, let alone accept these contradictory realities for what they are.

"What I recorded was the direct, raw aftermath of the wars. The period when the dust starts settling and life starts picking up again, but everything still remains shady and uncertain"

-

Another of the book’s qualities is its representation of specific Balkan nations during the fall of communism. Was there a sense of contagious optimism, of hopes for a better future among the crowds of those times?

What I mostly recall is the anxiety. What you just described was not yet there, or at least it was not yet as visible – that must have come along later, around the mid-90s. What I recorded was the direct, raw aftermath of the wars: the period when the dust starts settling and life starts picking up again, but everything still remains shady and uncertain.

In the former Yugoslavia, there was a heaviness related to [growing] nationalist sentiment, a sanitizing element of correctness, a heavy investment in minor things which were elevated out of all scale, revered and sanctified.

In contrast, one of the most interesting things I recall from that era is the bitter sarcasm and self-deprecating attitude towards the future that one encountered in Albania, which, at least in my eyes, registered as a healthier reaction [to the situation]. It was as if they didn’t take themselves so seriously, standing almost in awe of what they had tolerated, and astounded by the amount of time they let it last. Like children in a dystopian wonderland. Still, they were putting themselves in the equation, taking on a role that entailed at least some – belated – sense of agency and responsibility.

Meanwhile, in Romania and to an extent in Bulgaria, there was a widespread sense of victimization. At the same time, Serbs, Bosnians and Croats continued to be part of the problem due to the upsurge of nationalism. Optimism wasn’t allowed to kick in before efforts to eliminate opposing forms of nationalism did, which inevitably led to the elimination of each other. Turkey, on the other hand, was going through a period of innocence regarding its feelings toward the West: looking at it as a beacon of light, democratization, and human rights.

Of course, not everything went as planned. There can be a sense of post-communist nostalgia in those who have lived under communist rule: at the same time as people are fighting for and dreaming of a better future, some have inherited a desire to go back to the old times. What is it that makes faith in the future and longing for the past so intertwined in this region?

So true. All these emotions were intertwined with great expectations for an imagined future. Something the people of the Balkans had constructed in their minds, or in their collective consciousness. They invested in this, possibly expecting a fast-track transition to something resembling a capitalist paradise. Even if that ever existed, such a transition, or any transition, would not happen overnight, it would require a long duration.

Waking up to that reality, they probably felt betrayed – a sentiment common around the Balkans – and dealt with it in their different ways. Often they resorted to the comfort of whatever little they had before: limited yet concrete. Things may not have been great, but they were what they were, and the little that they had was suddenly safer than uncertainty. All this change, and the insecurity it brought along, was ever so confusing.

"Nationalism is the monolectic answer: what Milosevic did then, what Erdogan does now. Once ignited, the snakes come out."

-

You have mentioned the paradox of the Balkans, the establishment of visible and invisible borders in order to define and separate communities that bear so many similarities to each other. In your opinion, how did that paradox impact the collapse of Yugoslavia during this period?

Nationalism is the monolectic answer: what Milosevic did then; what Erdogan does now. Once such movements are ignited, the snakes come out. Whole communities and people are manipulated to serve political agendas on the basis of a sentiment that is not at all organic within communities because it does not nurture and sustain real bonds, only abstract allegiances.

Why were you interested in capturing the lives of people on the fringes of society, the Romas and Greek Muslims?

The margins are part of the whole. What you encounter there not only sheds a better light on the rest but also defines it.

"The Balkans are a bridge between the north and the south, the east and the west. Who belongs on a bridge? And to whom does a bridge belong? "

-

Through your images, it seems that you attempt to situate and reclaim a place of transit and transition, in contrast to works by outsiders that have depicted these communities as errant or deviant. Overlooked for too long, neither European nor Asian, what is the Balkans’ place in the world? Who does belong there?

The Balkans are a bridge between the North and the South, the East and the West. Who belongs on a bridge? And to whom does a bridge belong? Antagonistic elements that contradict each other, and agonizing emotions. A place that haunts you, while remaining your reference, your source, or your place of ultimate belonging. After all, it is in such rawness that we can all recognize a part of ourselves. Not the cradle of civilization, but the rawness of the womb.

For me this work is a self-portrait: my work in the Balkans depicts my own sense of belonging, the place where I can stand closer to my own emotions and live by them. It is as personal as it can get, how I try to make sense of the world, what keeps me alive, what nurtures my soul. And by that, I don’t mean the Balkans per se, but the place of one’s imagination: a place in the sense of the emotions that inhabit it, what I look for wherever I go, what I live my life seeking.