The Ordinary Made Extraordinary: Martin Parr in Black and White

A new photobook charts Parr’s early work - much of it made in the British Isles - from Butlins holiday camps to the isolated chapels of Yorkshire and Manchester’s working class terraces

Perhaps best-known today for his vibrant, color work, Martin Parr spent the late years of his education and early years of his photographic career documenting fast disappearing aspects of life in the British Isles in monochrome. Institutions as disparate as the Church of England, Butlins holiday camps and soon to be shuttered mental homes offered the photographer settings in which to hone his approach and define his areas of visual interest. These images of the urban working class and isolated rural communities are collected in a new photobook, Early Works, alongside some images from his early photographic travels abroad.

Val Williams is the author of Martin Parr, first published by Phaidon in 2002, and the curator of the 2002 Barbican Art Gallery retrospective exhibition Martin Parr: Photographic Works 1971-2000. She is UAL Professor of the History and Culture of Photography at the London College of Communication and co-editor of the Journal of Photography&Culture. Here, Williams reflects on Parr’s early work made in the British Isles.

Early Works is published by RRB Photobooks and Martin Parr Foundation, and available here.

"Parr is attracted to the territory which change marks out, he is fascinated by taste and the choices that people make"

-

When Martin Parr began photographing in the early 1970s, the photographers whose work he most admired – Gary Winogrand, Tony Ray-Jones, Robert Frank and Bill Brandt – worked primarily in black and white, adopting a quiet methodology to observe the world around them, concentrating on gesture and idiosyncrasy. For Parr, photography in the 1970s was primarily an exploration of hidden worlds and obscure practices, all under the mantle of ‘the ordinary’.

Parr is attracted to the territory which change marks out, he is fascinated by taste and the choices that people make. Like many of his contemporaries, he was a product of a cultural revolution in Britain, propelled by the emergence of the post-war Welfare State and the growth in the scope and accessibility of further education. Shaking off the patrician mindsets of art history and connoisseurship, there was increasing interest in the ‘democratic’ arts, film, photography and video and a corresponding rejection of high culture.

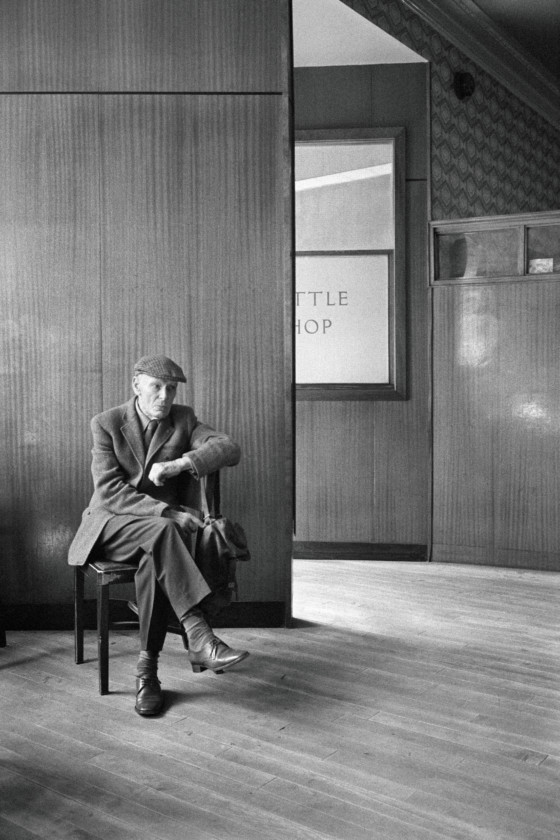

Parr’s first cohesive photography project was his documentation of Prestwich Mental Hospital (1971), in the North West of England. Though he had grown up just outside London, in suburban Surrey, it was the North which inspired his work throughout the 1970s. He photographed at the hospital for three months at the same time as continuing his studies at Manchester Polytechnic not far away. The Prestwich project introduced him to the idea of immersion – spending concentrated periods of time completely engaged with the subject, returning again and again over time, contrary to the prevailing photojournalistic approach popular at the time. Parr’s self-set early assignments, carried out with all the rigor of a professional, were a test of his ability to gain and retain access to privileged areas, and to emerge from the project with a coherent and effective body of work.

The partnership between Parr and fellow Manchester student Daniel Meadows produced two remarkable bodies of work in the early 1970s: June Street in 1972, and Butlins by the Sea in 1971. Parr and Meadows were fascinated by the northern values epitomized, for them, by the ITV soap opera ‘Coronation Street’. June Street, a row of terraced houses in Salford, Greater Manchester, became their ‘Coronation Street’ and together, they photographed the residents of each home, producing a set of photographs which, almost 50 years on, remain a testament to the power of collaborative, community based documentary of ‘ordinary’ lives.

"Martin Parr’s early black and white photographs of the North of England are a remarkable record of an all-but disappeared society"

-

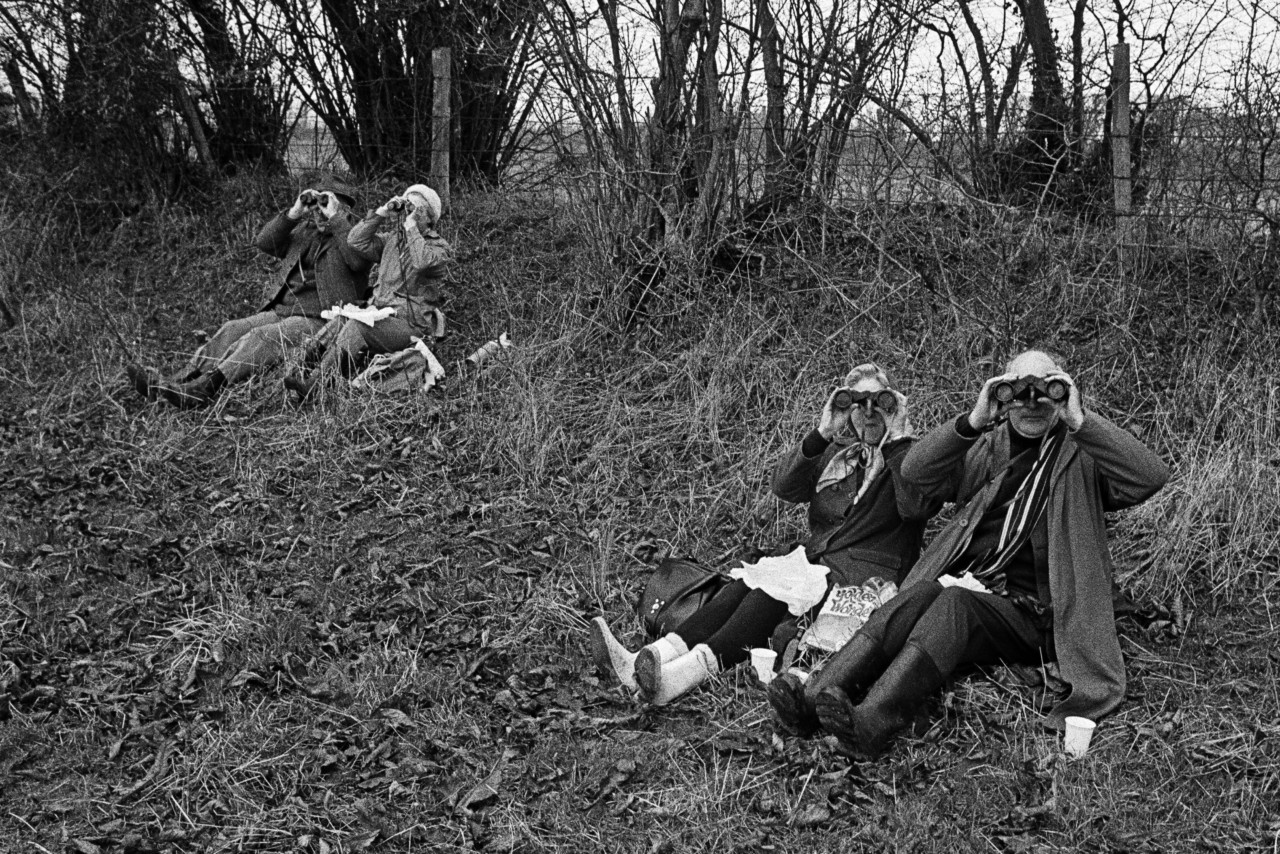

Parr’s photographs of Butlins (a British chain of family-focused seaside resorts) made in East Yorkshire in the early 1970s, while still a document of working class Northern lives, are of a different order. The elaborate scenarios invented by Butlins for its primarily working-class guests – comedy competitions, non-stop entertainment, high camp themed bars – were set in juxtaposition to homely wooden chalets and vast communal dining rooms. Parr reveled in the contrasts.

In 1972, he settled to the north east of Manchester, in the west Yorkshire mill town of Hebden Bridge. Though the mills were rapidly closing, the back-to-back houses and the social fabric of the smaller mill towns remained.

Hebden Bridge was an intricate fabric of social organization, and Parr was fascinated by the many clubs and societies which flourished there. With some fellow ex-students, he rented a small shop and set up the Albert Street Workshop, which showed photographs, paintings and ceramics. Though he photographed Hebden Bridge life with great enthusiasm (one of his favorite subjects was the Ancient Order of Henpecked Husbands) and produced many memorable images in the town, the great achievement of his Hebden Bridge years was his documentation of Crimsworth Dean Methodist Chapel, high up on the moors above the town. Together with his future partner Susie Mitchell, Parr immersed himself in the life of the chapel, photographing, interviewing and taking part in events there. For him, the chapel was ‘the icon of Hebden Bridge’s dark and gloomy, rather miserable past’ and the photographs he made at Crimsworth Dene and other Methodist chapels were an elegy to a passing way of life, somber and poetic, with an occasional whisper of humor.

"In the late 1970s, Parr moved to Ireland, where many intriguing photo opportunities awaited him"

-

In the late 1970s, Parr moved to Ireland, where many intriguing photo opportunities awaited him: abandoned Morris Minor cars became homes for nesting hens; brand new bungalows built by aspiring farmers, weekly dances at country ballrooms, sheep fairs, hay sales and bad weather. Parr’s Ireland photographs were the last of his black and white documentary series.

When he returned to Britain in the early 1980s, he began to photograph almost entirely in color, entranced by the radical work of American photographers such as William Eggleston and Joel Sternfeld. The Britain to which Parr returned after his years in Ireland was changing rapidly; consumerism was rampant and the social fabric which he had admired so much in northern England was rapidly fraying.

Martin Parr’s early black and white photographs of the North of England are a remarkable record of an all-but disappeared society. When we remember the 1970s, our vision is informed by Parr’s photographs: lyrical, solemn, respectful, full of longing; the ordinary made extraordinary.