Photography and Modern Conflict

Jérôme Sessini, Thomas Dworzak and Julian Stallabrass discuss the changing role of photography in covering wars

Magnum Photos is an agency whose very beginnings are rooted in the coverage of wars; co-founder Robert Capa was named “the greatest war photographer in the world” by Picture Post, and his coverage of the Second World War included the only photographs of the D-day landings. Not long after, the Magnum Photos agency was formed. “As those wars were fought from the 1930s onwards, the role of photojournalism evolved with them. War became seen as the ultimate testing ground of the new photography as published in illustrated magazines,” said writer, curaor and critic Julian Stallabrass, speaking at a Magnum Photos Now event on the topic at the Barbican in London.

As he observed, “The battle lines, both military and ideological, were quite clear, as was the role of the photojournalist as an image-making handmaiden of war.” Warfare has changed drastically since those days, and yet Magnum photographers have continued to document its manifestations. Magnum photographers Jérôme Sessini and Thomas Dworzak, who have both photographed conflicts throughout their careers, discussed how the role of photography has changed.

"War became seen as the ultimate testing ground of the new photography as published in illustrated magazines"

- Julian Stallabras

Willingness of participants of war to give access

The willingness of the people participating in a war to give photographers access depends on their personal motivations and the perceived benefit of them doing so. Stallabrass described how Susan Meiselas’ famous work documenting the successful revolution in Nicaragua became a political tool for those who wanted to use the work to gain support for the radicals fighting the dictatorship:

“30,000 people were killed, overwhelmingly by government forces, in twelve years of civil war. This violence was meant to be visible locally: mutilated corpses were dumped in the street or by the roadside, as warnings to those who would resist… Exemplary violence was supposed to terrify ordinary El Salvadorians into passivity, but neither the dictatorship nor its US sponsors wanted images circulating more widely. In the US, Meiselas’ pictures became tools in a political controversy, in which radicals sought to expose the rampant human rights abuse that came with support for the El Salvadorian dictatorship.”

"In the US, Meiselas’ pictures became tools in a political controversy, in which radicals sought to expose the rampant human rights abuse that came with support for the El Salvadorian dictatorship."

- Julian Stallabras

More recent, and complicated, revolutions have not been as clear cut, as Stallabrass exemplified with Tim Hetherington’s coverage of the civil war in the Congo. He explains that in situations like this: “the ideological issues at play are far murkier, if they are drivers of war at all. The competing sides are generally composed of small, informal militia forces, which may suddenly shift allegiance, and what these forces want from photojournalism is far from certain. These militia groups usually avoid direct combat with each other, preferring to conquer and hold territory by terrorising civilians, and then exploiting their captive populations and land to the hilt. The resulting wars divide people by ethnicity, tribe or religion as groupings from which to loot an area of diamonds, gold or coltan, funding continuing warfare and enriching militia leaders. Violence is often extravagant and put on display—a dismembered and tortured body is dumped in the street, for example—to frighten people into compliance or drive them away. Usually, a wider display of that violence in the media is unwelcome.”

A tool of warfare

Jérôme Sessini concurred that it is hard – and getting harder – to get access to the front lines, but explained that participants in war might grant access to photojournalists as a strategic tool: “When the Libyans give you easy access to the front line they think your presence is good for them. It’s the same in Syria. And then when they realise that it doesn’t make any difference for them it starts to be more difficult for us – and now it is impossible.”

And while groups fighting in civil wars may shun documentation from photographers, some are publishing images of their own via social media. Islamic State (Daesh) militants have been documenting their own acts of war and torture, publishing them via social media for some time, and it is a well-discussed theory that many of their attacks are so targeted for the likely media attention they will attract.

It is against this backdrop of a shift in the way modern warfare interacts with the media that Magnum’s Stuart Franklin criticised the awarding of the 2017 World Press Photo to Turkish photographer Burhan Özbilici, who went to cover a press conference at an Ankara art gallery on the way home from work on December 19, 2016 and ended up photographing the moment the Russian ambassador to the country was murdered by a gunman, shouting, “Don’t forget Aleppo.”

In a piece for Magnum, Stuart Franklin explained that he didn’t vote for it because it allowed terrorists to use the photography in their way; “by awarding this image the top prize it would be furthering the compact between martyrdom, or lone wolf acts of terror, and publicity; that in glorifying in some higher way the image would be playing into the hands of the perpetrator by replicating his ‘performance’ and expression of power.”

"The media gives a very binary view on wars. This is the reason I was not really interested in war itself but to confront myself with reality and to look to find a truth."

- Jérôme Sessini

A different perspective on war

Whilst early war photography captured the on-the-ground experience of conflict and brought the realities of the violence of war to largely unaware audiences via magazines and newspapers, the rise of rolling news, citizen journalism and social media means there is little demand – and money – in this kind of conflict photography now. Instead, war photographers are offering different perspectives on war. For example, Tim Hetherington’s “Sleeping Soldiers” in Afghanistan, and sitting portraits, taken on a Hasselblad, of rebel fighters in Liberia hint at the conflict surrounding them, whilst offering an insight into the personal worlds of those involved; and Paolo Pellegrin’s extensive work charting the conflicts of the Middle East aimed to unpack the complexities of the motivations of those involved.

Jérôme Sessini, who also covered the Libyan conflict, is taking a long-form approach to documenting the conflict in the Ukraine. After the main revolution in May 2014, a counter revolution emerged in the east of the country in the Russian-speaking Donbass, where Sessini decided to focus his work.Talking at the Magnum Photos Now event, Sessini said: “The way I approach photography has changed since the Libyan conflict. The media gives a very binary view on wars. This is the reason I was not really interested in war itself but to confront myself with reality and to look to find a truth. Libya changed my vision because I was a little bit naïve about revolution, like a lot of people. It sounds very nice and romantic but once I was there I realized very quickly that something was wrong and maybe it was not the good way to change the country. Of course Gaddafi was wrong, but now I look at what’s happening in Libya five years after and the change is far from perfect. I tried not to follow my emotions, but to find a distance with the subject and I tried to anticipate what could happen after. I am trying to gather evidence, and maybe I will reach a point where I will understand.”

A tool to contextualize

A longer-form documentarian approach enables a broader perspective on a conflict, but with the rise of social media there is another space which is occupied with imagery for and from wars, a world which is largely undocumented. “On Instagram and other platforms, war imagery could be shown to numerous followers, far and near, military or civilian, in close to real time. Images of war were also jumbled in among all the other typical contents of the Instagram feed: celebrity portraits, pets, selfies, meals and snapshots of loved ones,” observed Julian Stallabrass.

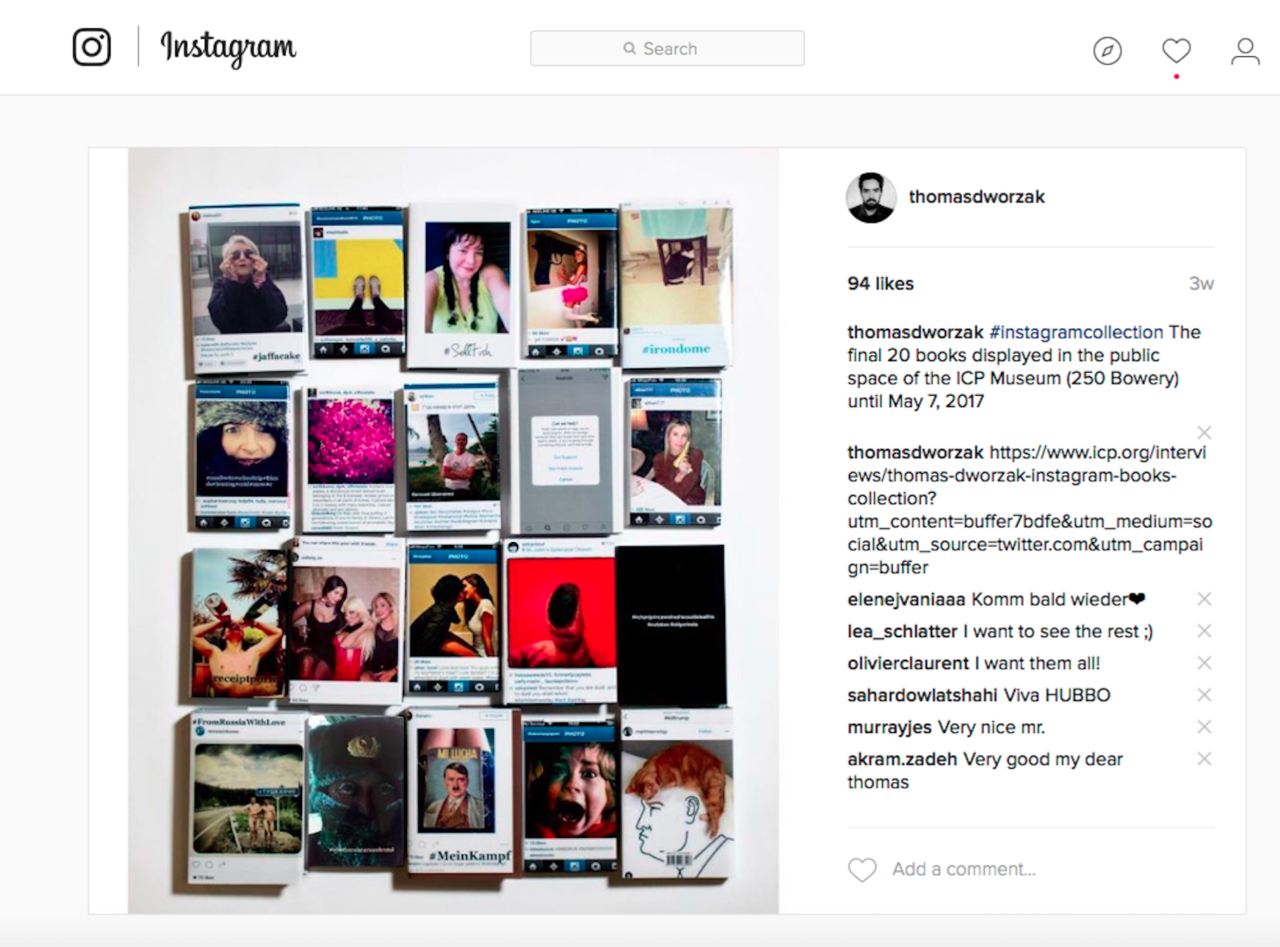

Magnum’s Thomas Dworzak, who has documented conflicts in the Caucasus and Afghanistan, amongst others, has a fascination with the digital space. Much of his current practice is concerned with the digital realm, and he has attempted to document and make sense of this with curations of Instagram feeds, which has manifested in a series of 20 self-made books, recently shown at the ICP Museum.

Some of these books focused on the war in the Ukraine. One was a curation of images from the account of a man who was a commander in eastern Ukraine. Dworzak dug back into his subject’s account to discover a life that was utterly banal and normal before it slowly drifted into war. “What’s interesting for me is there are pictures of his very banal life – I think he was an advertising executive – travelling around eastern Europe in his Passat, visiting Krakow and spending his holidays in Bali, and slowly there are little blinks of war: first he has a black eye, and then he starts buying a flight jacket, and learns how to shoot, and then over the course of one year he ends up being in the forces. Usually when you cover a war you come at the point when people are already in the war, you don’t usually meet them before the war breaks out,” he said.

These explorations came into their own during the 2013 Boston Marathon attack, which played out live on social media. “The feeds began featuring runners, and quickly turned ugly, and then the man-hunt happened in a place which had a high concentration of Instagram users, so these people were documenting from inside the houses when the SWAT teams were going through the streets,” says Dworzak. “It’s something I like to do and I try to do in my normal life,” he says, “but I cannot imagine that I’d be able to be in someone’s kitchen when the SWAT team comes in.”

"Usually when you cover a war you come at the point when people are already in the war, you don’t usually meet them before the war breaks out."

- Thomas Dworzak

Documenting the digital world itself, Dworzak’s Instagram explorations become more than just an access point to information and images, but are a vehicle for exploring the rules which govern this digital world, its practices, customs and dark corners. In the days and weeks following the Boston attacks, Dworzak’s hunting led him to uncovering teen girls obsessed with the perpetrator of the attacks, who had built a whole community around specific hashtags.

Another project saw him exploring the Instagram posts of school trips to Auschwitz. Having grown up as a school kid in Germany, going to concentration camps on trips was something he’d experienced himself, and as a photographer, he has thought about how these places should be dealt with photographically. Delving into the world of Instagram hashtags of school trips to Auschwitz revealed “a very strange mix” of teenage preoccupations, excitement, crushes and selfies, jarring with the gravity of the locations they are set against. A similar delve into hashtags saw Dworzak looking into pro gun-ownership posts during the days following a high-profile shooting in the United States. The resulting self-made book collated images of American teens posting with guns, pieced together using the public images they had shared on their Instagram accounts.

Read about more discussions from the Magnum Photos Now events here.

For a photojournalist figuring out how he might document a world that exists solely in a digital realm, Dworkak’s Instagram curations have given him a way to chronicle something that is “very hard to report on in a classic way”.