Slow Journalism: Jesse Lenz

The Creative Director of The Collective Quarterly on immersing yourself in your subject

Jesse Lenz is the Creative Director and co-founder of The Collective Quarterly, a printed publication that develops each issue by immersing a team of writers, photographers and creatives into a specific location. The resulting work is an in-depth exploration that uncovers stories using what Lenz describes as ‘slow journalism’. Lenz has also worked as an editorial illustrator, creating covers for some of the most well-respected titles in media around the world, including The New York Times Magazine, Newsweek, Rolling Stone, Entertainment Weekly, and many more. He lives in Ohio with his wife, three boys, and two puppies. Lenz spoke to Magnum as part of our Photography Insiders series, where industry experts share their insights and inspirations. His interview is accompanied by a curation of images by Lenz, along with his commentary on them.

Do you have a favorite body of work or photographer?

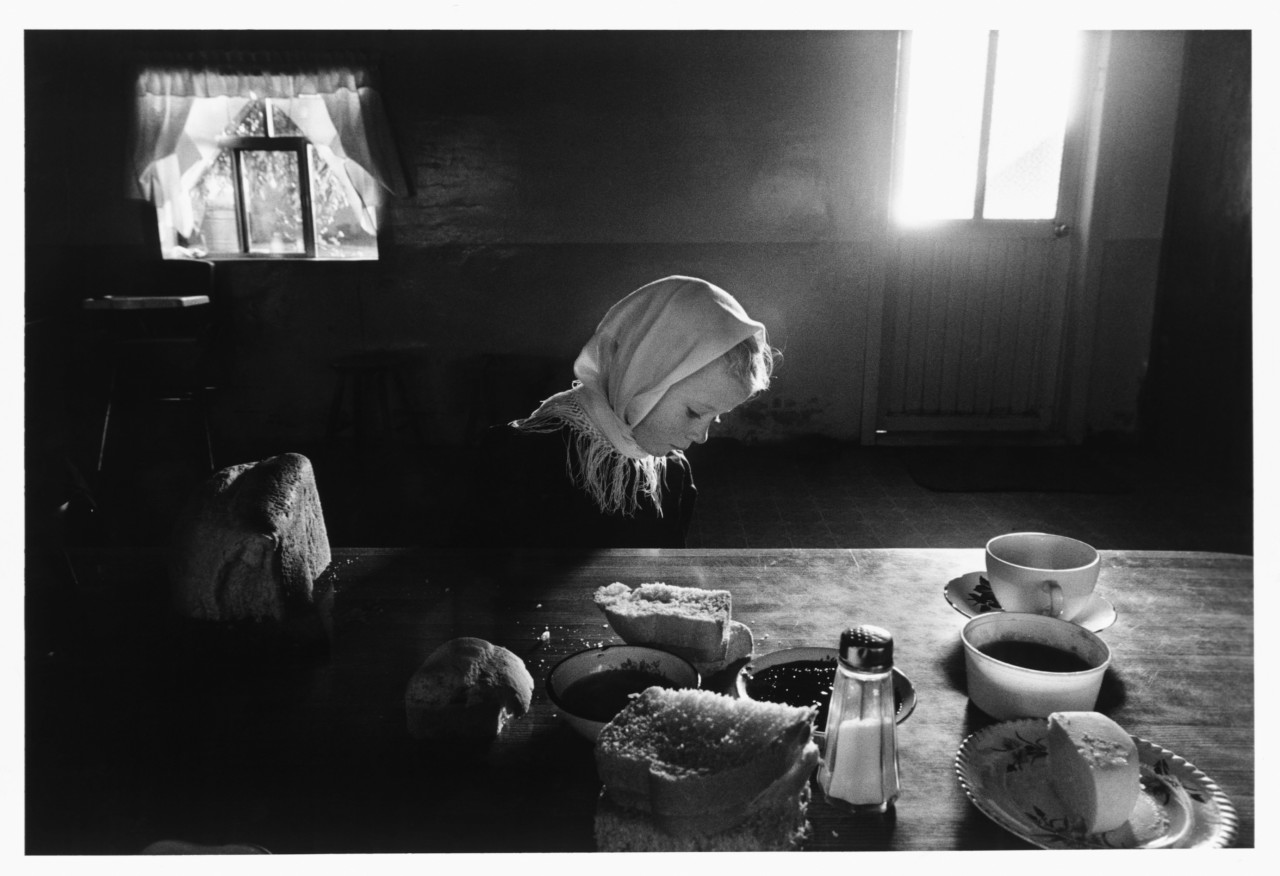

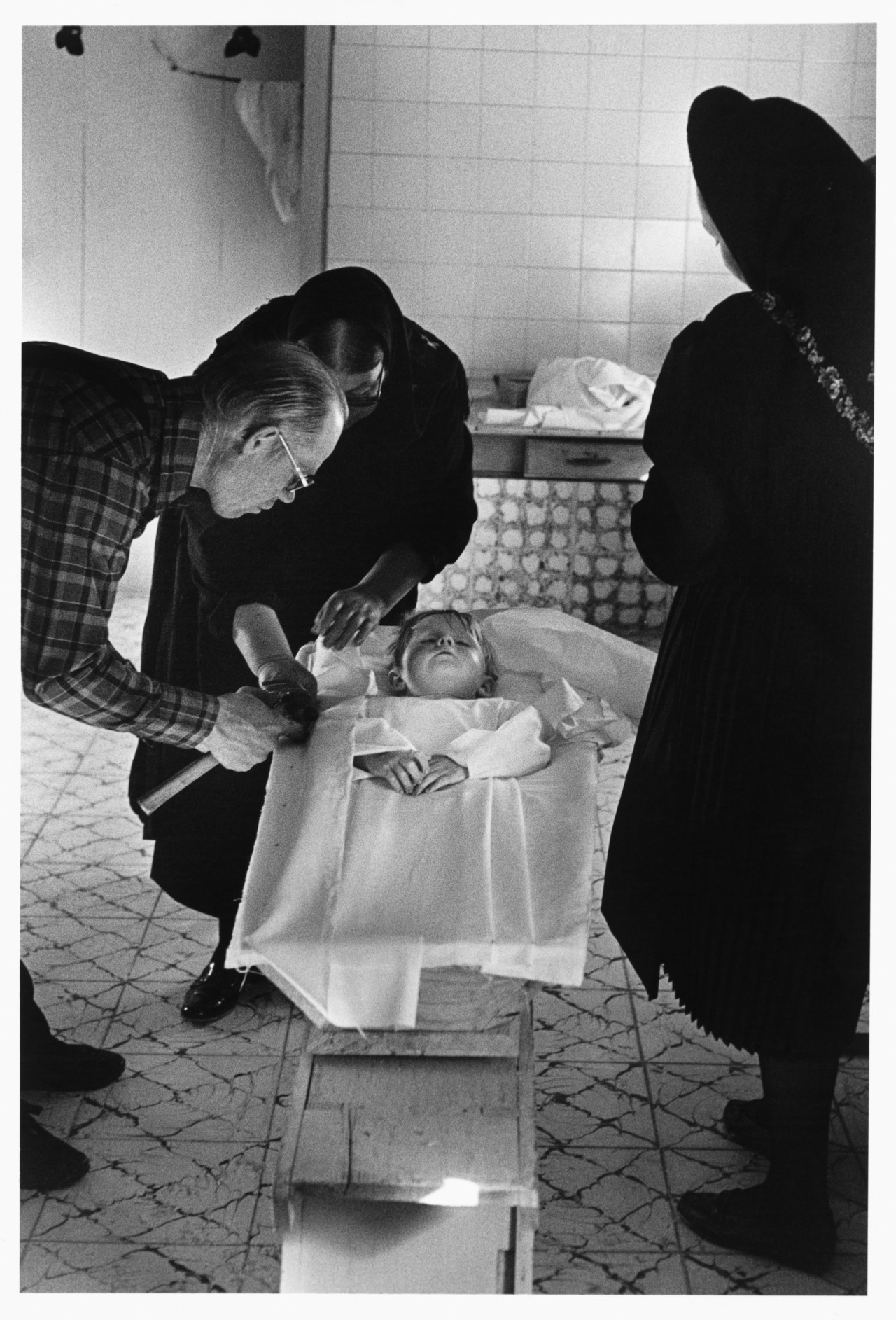

Right now, it’s Larry Towell’s work on the Mennonites. Larry’s work is unique because there is such tenderness to it. In photojournalism, it is easy to revert to ‘shock-and-awe’ photos, but his work conveys dignity and respect, regardless of lifestyle and personal choices.

Having founded a company that is run by young creative professionals, how important would you say collaboration has been to your success?

Incredibly important. Collaboration means you have a team of equals and each have their own pride, insecurities, and strengths. You have to navigate these things gently because usually there isn’t much money involved. Most people will stop when things get difficult, but if you push through that (as you do when you are doing a paid job and you disagree with the editor or creative director) you can arrive at a final product that is truly unique and special.

Your approach with The Collective Quarterly involves going to a location and really immersing yourself there for a period of time – could you explain what the process is and how this results in editorial work?

It starts with lots of research into a region where a movement is happening. We believe that a good profile article figures out the central challenge in a person’s life and how they’re trying to overcome it on a daily basis, and we try to apply that approach to places.

We make as many connections on the ground as possible, then we go for a 10 to14 day scouting trip. The scouting trip is about meeting people, letting them see you around so when you come back they remember you, like a first date.

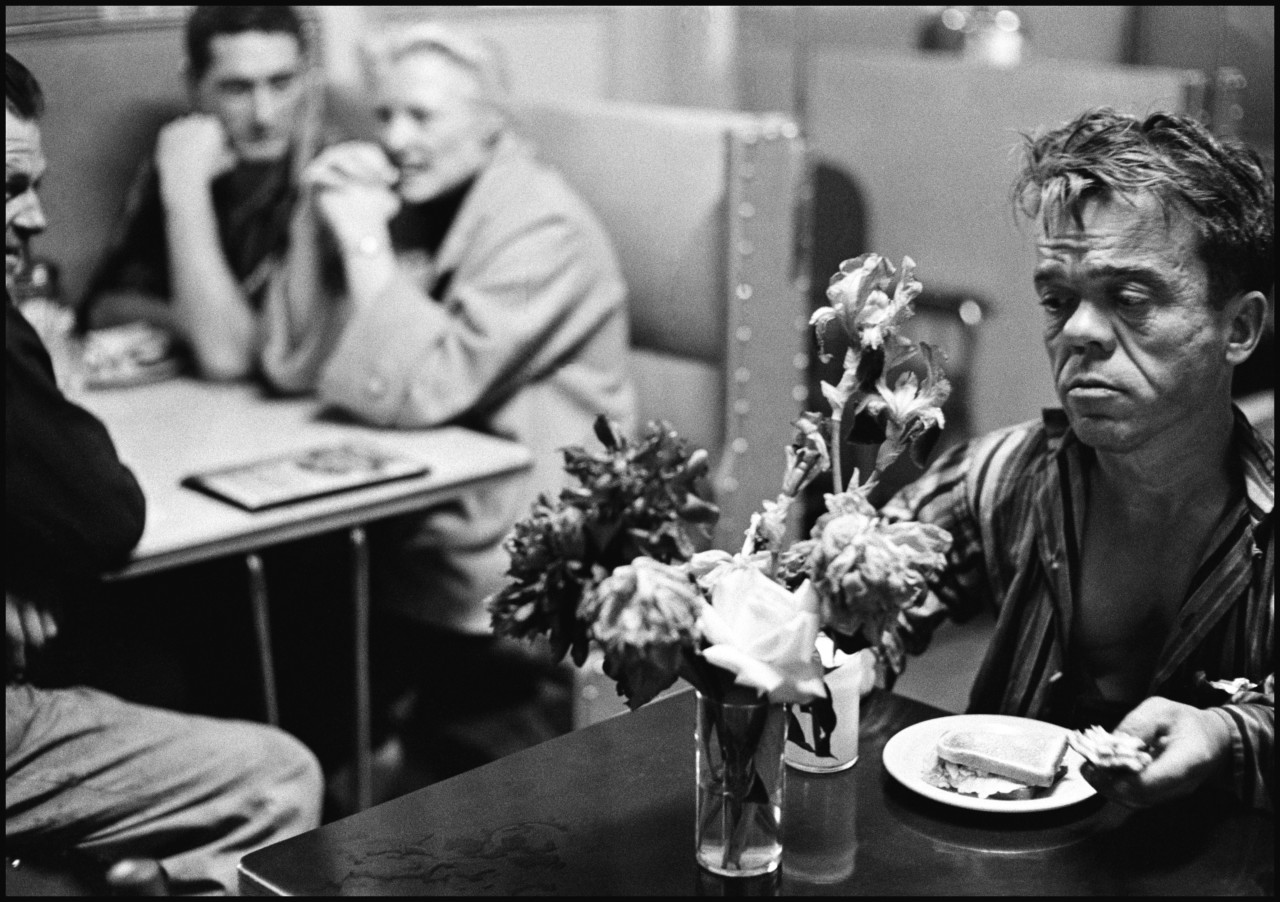

We hang out in the local diner and talk to the old timers and waitresses. We go to dive bars and talk the the most interesting people we can find. We hang out at skate parks. We get to know people, ask them questions about their life and the place, and ask them who they thought the most interesting person around was, then we go looking for that person.

After two weeks of that, you know a few people. They’ve invited you to dinner at their house and you have their phone numbers. You let them know you are coming back in a few weeks and you’d love to meet back up and do something cool or fun with them. You stay in touch and build the friendship.

By the time we get home we have a pretty good idea of what the ‘feel’ of a place is and what stories need to told to reflect that feeling. From there you can plan a concerted approach to a place in print.

What does this approach give you that is missed when a journalist or a photographer just go in and out to get a job done?

Curiosity. When you go somewhere with preconceived notions, you aren’t curious about anything that doesn’t line up with that. When you are reporting at the behest of an editor, you already know the ‘story’, and you are getting exactly what you need and then you are getting out. I made this mistake at the beginning.

How do you identify the places that have what you call the “X-factor” and are deserving of a deeper delve?

This one is hard to explain, because it’s a combination of a lot of factors that have to come together:

- A place has to be somehow isolated or hard to get to and hard to make a life in;

- It has to have some sort of limiting factor (weather, economy, isolation) that guarantees it never really growing too much—in fact, sometimes the population is actually decreasing; It has to be self-aware in some way. These are places that have been points of convergence for centuries, and typically exist in the periphery of some geographic beauty: mountains, islands, etc. Places where people passing through are so deeply moved by something in their soul that they forsake their old life, move there, and spend the rest of their lives solving the creative problem of “How do I make a living here?” When leaving is not an option. That conflict creates a desperation resolved by creativity that influences every aspect of culture in that region. People are open to new ideas, and they are working together as a community to survive.

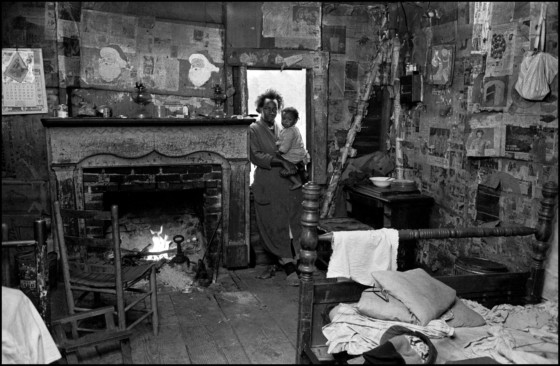

- There are plenty of small, remote places that do not have an X factor, I grew up in a place like that in West Virginia. It was a region that the culture defined by the act of extraction, taking something from the land and not giving anything back, without any stewardship. People view the land as a ticket out to a better place. Places like that are harder to find a symbiotic relationship between people and land. No one is trying to figure how they can stay there, only how they can leave.

Do you think this long-lead ‘slow journalism’ as you call it, is lacking in the media landscape these days?

Certainly. If it wasn’t, we could be making much more money doing it for someone else! It still exists, but everywhere it is strained and breaking down. Publishers aren’t making the insane profit they were when magazines and newspapers where the only news outlets. These institutions are built upon a profit-focused system, where the people at the top are not storytellers, they are investors. To do journalism correctly, you must have strong values and want to do it the right way, not the cheapest way.

In many ways, we feel about storytelling the way that people we document feel about the place they live. We know this is the right way and the right thing to do so we have to solve the creative problem of how do we sustain to continue doing it. It’s not about living the good life, but it’s about having the needed resources to do the job the way it needs to be done.

In the latest issue of Collective Quarterly you explore the Mojave and Sonoran deserts, what kind of stories were you able to develop that the causal visitor just passing through might miss?

Quite a bit actually. One of our photographers lived with a cowboy in a mud hut in the middle of the desert for about three months. But in all honesty, sometimes it isn’t that the casual visitor couldn’t find these stories, but they simply don’t take the time to or lack a reason to. If you think about it, most of what artists and writers do is show people the incredible world around us that we pass everyday and never really see.

Most people travel from point A to point B because they are on a mission to see something or to go somewhere, and they don’t take time to talk to the hitchhiker on the side of the road or the guy with an eye-patch walking into a bar at 10 a.m. We do.

In this issue, too, there is a mention of the writer John Steinbeck, who of course travelled with Magnum’s Robert Capa, famously creating ‘A Russian Journal’ together, featuring Steinbeck’s writing and Capa’s photographs. To what extent has this legendary pairing of a writer and a photographer, especially when travelling together to discover new places, inspired what you do?

Ironically, most of these legendary works of art have come on my radar way after we started this project. Not that we were ever under the impression we are doing something new, but the relationship between writer and photographer has always been one based on shared adventure. Now that we’ve been doing this so long, it is a constant point of inspiration to see the legacy we are following—and within that, we see the writer-photographer relationship as an intensely valuable and symbiotic relationship.

Jesse Lenz will be joined by Shannon Ghannam, Global Education Manager at Magnum Photos and other speakers from Time, Patagonia, Wired, Fortune and Men’s Health for the next Collective Quarterly workshop in Pray, Montana in March 2017. Apply now for an exclusive opportunity to network and showcase your portfolio to some of the most respected decision-makers in the editorial, commercial, and fine art industries. Applications close January 7th, 2017.