Refining Your Practice

Former students of the Magnum x London College of Communications Intensive Documentary Photography Course on how the tips they learned have influenced their subsequent practice

Each summer Magnum Photos teams up with the photography department of the London College of Communication (LCC) to offer an intensive short course in documentary photography. Led by LCC’s teachers and Magnum photographers and staff, students develop their skills in conceptualising, photographing, editing and presenting their work as well as building their knowledge around the business of professional photographic practice. After the course, students go on to apply what they’ve learned to their photographic projects, approaching them with a renewed sense of direction and confidence. Here we present the work of five LCC x Magnum students, selected by course tutors Stuart Franklin and Chris Steele-Perkins, sharing the tips most impacted on their practice.

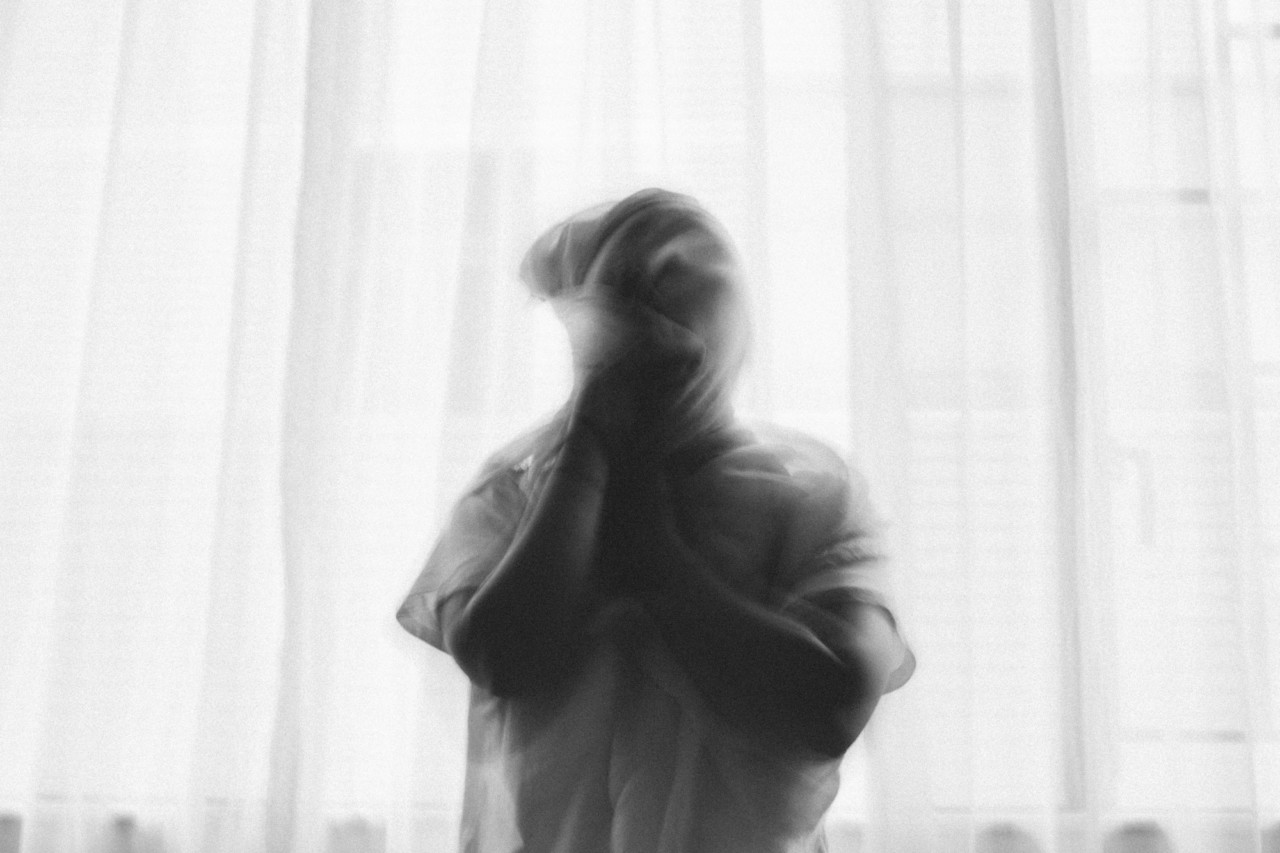

Emotionally engaged editing

Alejandra Edwards explores femicide in her ongoing photographic project. Since September 2018, she has been visiting homes of women or girls who have been killed, photographing their belongings and relatives, and the spaces they left behind in an attempt to get to know the women who have died. “You can feel the emptiness, the silence and pain with which the relatives of the victims of femicide live, the anger and impotence they experience knowing that their loved one has been brutally taken away from them,” says Edwards.

During this project the photographer spent time with women and families who have suffered unbearable loss, which presented a challenge in how to sensitively and accurately portray such emotions photographically. “This has brought me face-to-face with a reality which everyone is aware of, but which it is very hard to truly comprehend and even harder to communicate to the outside word,” she said.

“Once I had assembled enough photographs, I really spent time on choosing the ones that communicated the emotion and the idea that was driving my project,” she says. “Doing this, I learnt to discern which photographs worked best together and that my appreciation of which photographs and which order to present them in changed constantly as I developed a clearer understanding of what I wanted to say and how I wanted to say it.”

Although Edwards still works in a highly intuitive way, she is now more aware of how her images fit into a visual narrative. She also says that she has become more aware of her role as a photographer, in telling a story that is intensely painful for all those involved, “while remembering the loss of their loved ones is harrowing for the families, by registering their sorrow, rage and dignity I have told the story that I set out to do at the start of the project.”

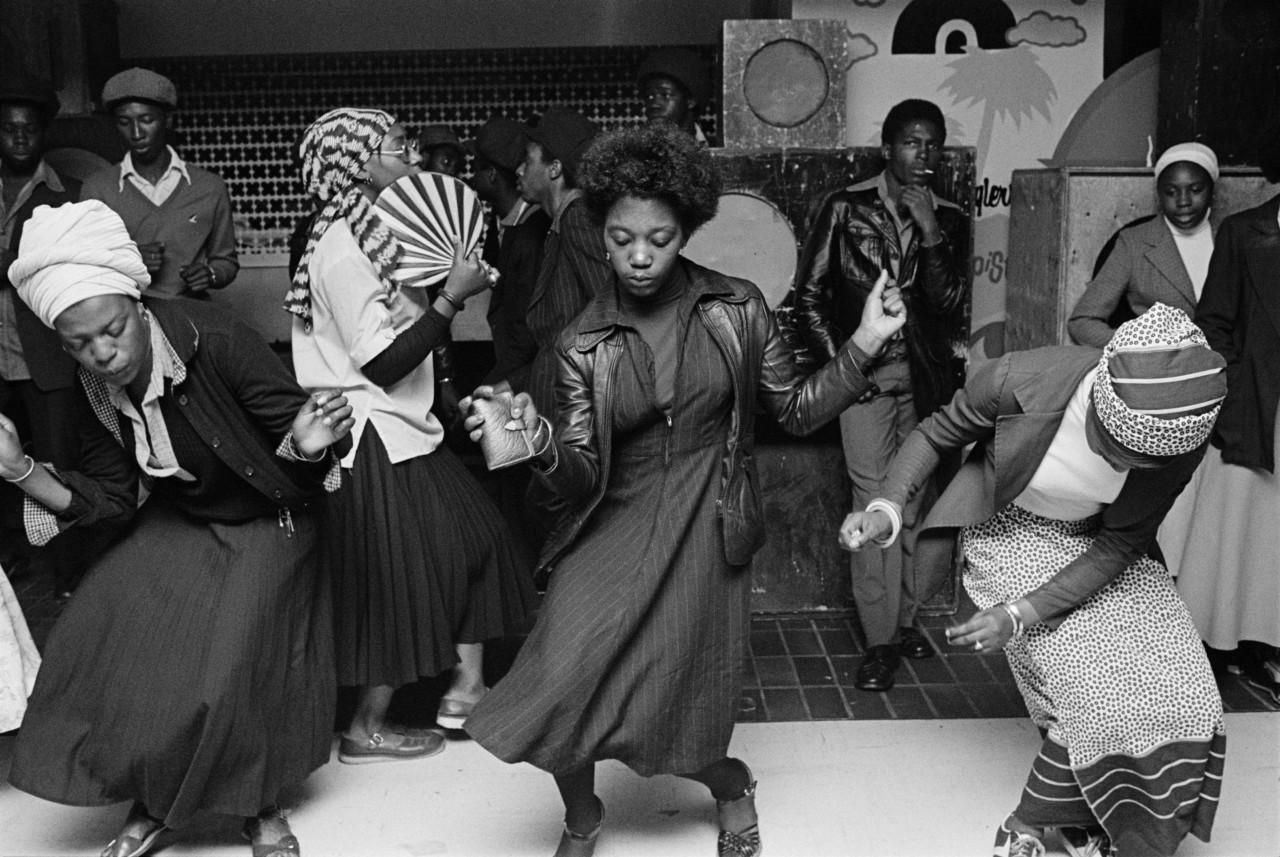

Holistic and interpretative storytelling

Stephanie Teng, motivated by an interest in psychology and human behaviour, explores photography as a form of therapy. In this project she applied this approach to the survivors of sexual harassment and assault in Hong Kong, a city where surveys show that many victims do not report incidents. The ongoing project aims to dismantle shaming culture by empowering survivors to step forward and heal from their past traumas.

“As a survivor myself, I wanted to ensure that each session with these women was created collaboratively – through conversation and collective healing,” says Teng. Her subjects choose how they are photographed and if they are identifiable it is their choice. “The women got to decide where to do the shoot and each portrait is a depiction of a key moment in their emotional journey towards healing.”

Teng learned to think about her storytelling in a “more holistic and interpretative way” during the LCC short course: “In a series rather than a single image; in a story rather than a moment; in a feeling rather than a thought.” She was particularly inspired by some guidance that Chris Steele-Perkins gave on finding a subject to photograph: “If it grabs you by the throat and doesn’t let you go, you’ve found something.”

“That spirit has inspired me to embark on a new (ongoing) project on sexual harassment upon returning to Hong Kong. I wanted to shine a light on a serious societal and cultural issue that often gets overlooked or pushed aside. By continuing to explore photography as a form of therapy in my current practice, I hope the project can empower survivors to let go of a piece of their past.”

Returning to a story and digging deeper

Simon Childs’ project was created during a trip from Newhaven, on the South East coast of England, to Dieppe in France. With no agenda in mind, Childs photographed what attracted him. The real work was to be done later, when it came to editing. Magnum Education Manager Sonia Jeunet helped guide him through the editing process. “I worked on different edits and sequences, but I felt I was not getting it right,” Childs says. Jeunet suggested he focus on the images themselves and what they represent, and the photographer developed a sequence of images which, despite not having a linking narrative, sit together.

For Childs, the editing process training in the LCC course was the most useful. “The course encouraged me to work intensively on my chosen project and to keep going back and digging deeper and finding more pictures,” he said. “This laid the foundation for setting my own projects and having the confidence to work on them, going beyond my normal comfort zone.”

Striving for visual coherence

Between October and December 2018, Christopher Preece photographed three seaside towns of his childhood family holidays: Weston-Super-Mare, in Somerset, and Aberystwyth and Borth in Wales. “As a six to eleven-year-old boy growing up in landlocked Herefordshire, these annual explorations to seemingly ‘exotic’ places were the highlight of the year.”

Stuart Franklin’s advice on visual coherence has stuck with Preece the most. Visual coherence is the idea of making a series of images that look like they are made by the same person, that have a consistent style. “The point was forced home that trying to make a single image that appears on social media for a few hours is so different to producing a body of work on a specific subject that tells a story, is coherent and suitable for publication in print or in an exhibition,” he says.

This has influenced the way Preece now approaches the shooting of his work, taking into account weather conditions, lighting, time of day, equipment, camera setting and processing. “When shooting over multiple days I look for consistent weather and lighting, which is not always easy to do in the UK, and can be frustrating when you have to travel some distance to a location. Mark Power touched upon this when he spoke to course students about his project ’26 Different Endings’, the importance and difficulties in getting the weather right to get the consistency he needed.”

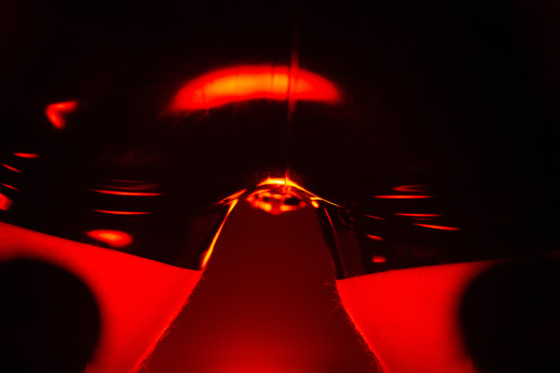

Embracing Ambiguity

James Barkley turned his lens to a world that was unknown to him, and usually considered taboo – kink. “As a society, we may have these desires deep within us, but they are often repressed through societal norms and other forms of oppression,” he explains. “I’m interested in dismantling this and instead of hiding away from it, exploring it and celebrating it.”

The photographer found that learning about the concept of ambiguity was useful to draw upon. “I obviously knew of the word before, but didn’t necessarily correlate it to my own photography. It really hit home that photography doesn’t need to explain everything. And in fact, if it raises more questions than answers, that’s a good thing.”

This new mindset has helped the photographer in his approach to all his shoots, particularly when it comes to the editing process. “Maybe in the past I wouldn’t select a shot that someone wouldn’t understand. But I kind of go with my gut, and choose shots that I myself find interesting. And hopefully others do too.

Prospective summer 2019 students can apply to this year’s LCC x Magnum Photos Intensive Short Course in Documentary Photography here.