Richard Kalvar: A Question of Feeling

The photographer discusses framing, composition, and the peculiarities and pressures of working in the street

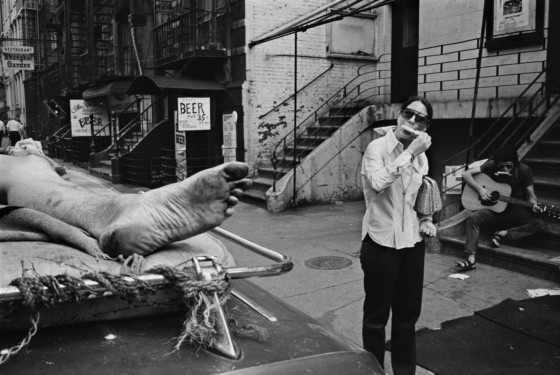

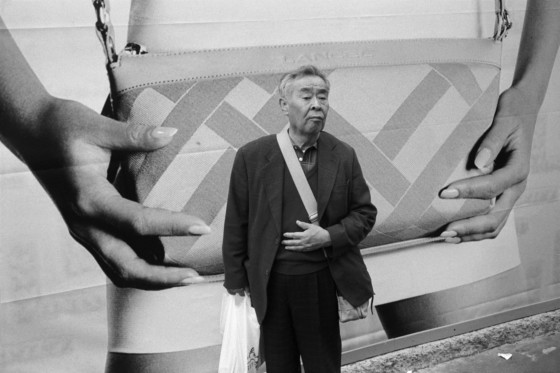

Richard Kalvar, one of seven Magnum photographers who lead the Art of Street Photography online education course, describes his approach to photography as “more like poetry than photojournalism”. Monographs of Kalvar’s – like Earthlings and the recently released Photo Poche and Photofile books – captured humanity’s inherent strangeness, and played with the abundant ambiguity of the everyday.

Here, Kalvar discusses his approach to photographing on the street: the demands of frenetic subjects, the importance of framing, composition, and focus – as well of course as the need for patience when pursuing fleeting moments. “Once in a while, I take a whole bunch of pictures and it was the first picture that was the right one, but that’s pretty rare. More often, it’s closer to the last picture.”

More information on the Art of Street Photography online course can be found here.

How important is composition in street photography?

You have to get the framing right. Without good framing you’ll have a picture that might be interesting only from certain standpoints. There may well be elements in the image that are interesting or that work, perhaps the subject is interesting, but the picture won’t be. Making it interesting involves getting everything right. And getting everything right quickly.

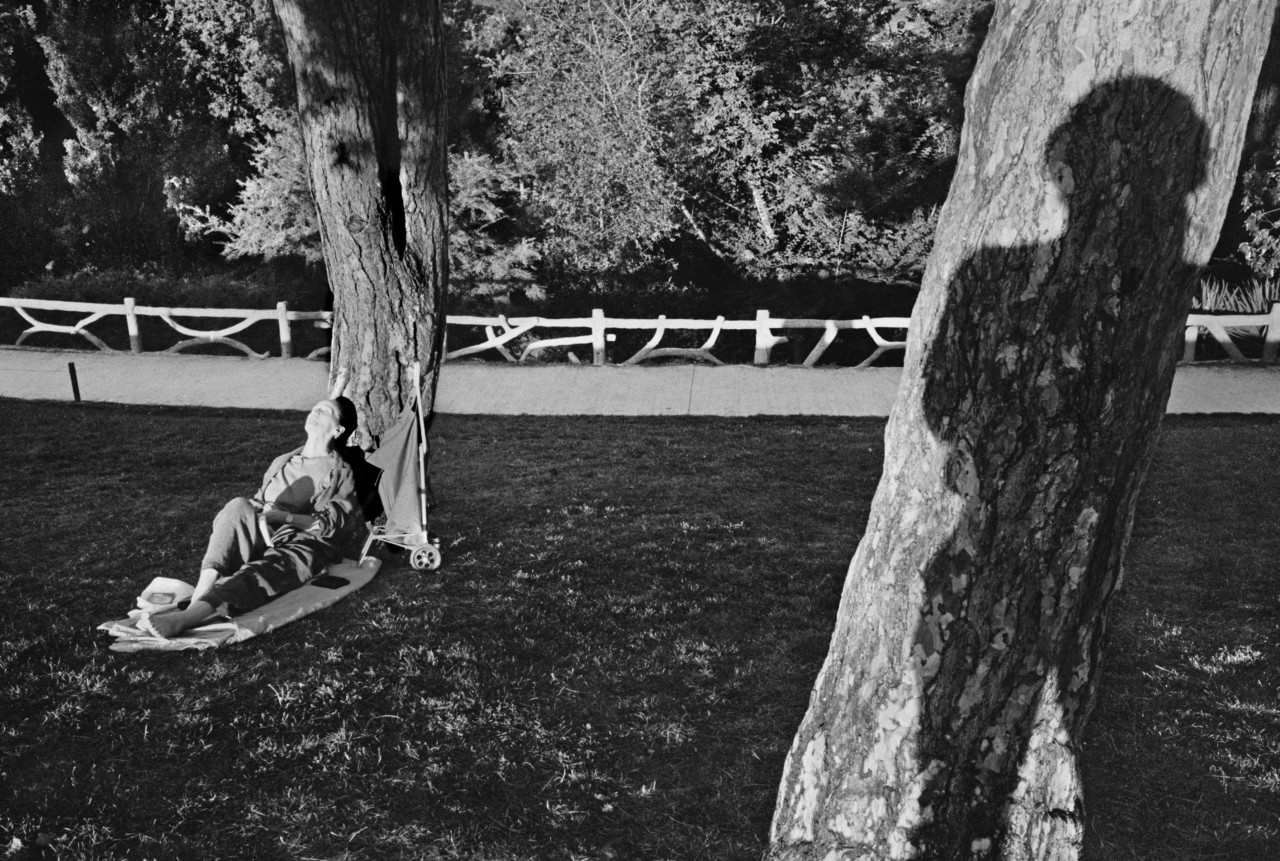

Photographs are abstract – they are an extracted piece of reality which is transformed into something that doesn’t move, something that’s limited in space within four walls. In this rectangle there are elements: the things that look like people, the things that look like dogs, things that look like buildings, trees or whatever… And these elements have a relationship within the rectangle. For me, a successful picture is one in which everything works together, or potentially against each other, but there must be relationships among everything in the picture, even if the connection is only visual. One of the elements, strangely enough, can be empty space, but it has to be there for a reason.

"One of the elements, strangely enough, can be empty space, but it has to be there for a reason."

- Richard Kalvar

Do you feel you have reached a point where you are almost framing and reacting without consciously thinking about it?

I think I have an instinct for the organization of my rectangle, whether innate or learned. I’m working with life: with the spontaneous and unexpected, where things suddenly change, where I suddenly change. I don’t know, I guess it’s self-discipline, or maybe it comes from experience, but you have to be thinking about the frame constantly, and you have to be quick on your feet. You have to do several things pretty much simultaneously.

I have to change my framing all the time because people are moving all the time. I have to be discreet – I have to pretend I’m not taking the picture and, you know, I’m dancing around, while the people I’m photographing are dancing around. It’s not easy. But you have to do it, because if you don’t then your photos don’t hold together, like a movie where the sound is bad. And no one wants to watch a movie where you can’t hear what people are saying.

"If you work with unposed subjects moving quickly and doing unexpected things in a complex environment, you have to make a lot of decisions rapidly and as instinctively as possible"

- Richard Kalvar

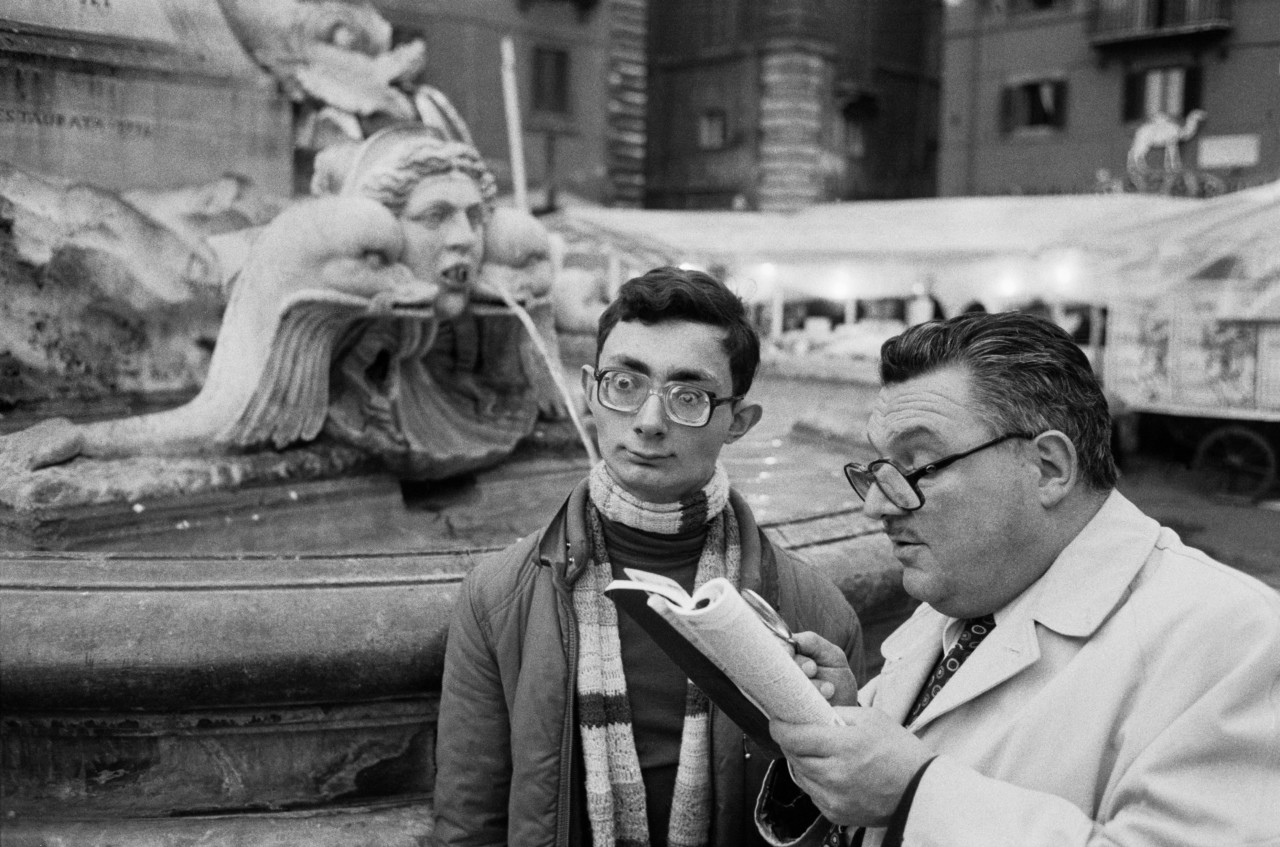

You also have to focus – this is of course very important – and you have to organise your picture. When you have elements at different distances from the camera, choosing the thing you focus on is critical. In a conversation among three people, say, which one will you have the most in focus? It makes a big difference to the meaning – and to the success – of the picture. After 50 years of doing this I still make stupid mistakes. When I see the results, I ask myself why I focused on that unimportant guy on the right instead of the key person over on the left? It’s something to be aware of.

The more you master – through education or experience – the technical side of things, the more you can control the way the picture will look to other people, which is the finality of photography. If you work with unposed subjects moving quickly and doing unexpected things in a complex environment, you have to make a lot of decisions rapidly and as instinctively as possible. Which shutter speed? Which aperture? Where to focus? How to balance the trade-offs among shutter, aperture, and film or sensor sensibility? How to hold the camera? If these things become automatic or semi-automatic, you can then concentrate on the more interesting stuff.

You generally use a 35mm lens when creating your personal work; and you have said that this forces you to get close to your subjects. How does that impact composition?

Getting closer, particularly with a slightly wide-angle lens like the 35mm, intensifies and simplifies the composition, and makes for a more intimate image. There’s less unwanted extraneous stuff going on. I don’t crop my photos, so I have to do the organisation of the frame in the viewfinder while I’m taking the picture. Being closer helps.

I often take a lot of pictures. If you look at my contact sheets you’ll see a lot of crap. I don’t know what’s going to happen but I’m on the lookout, and I’m starting to press the button. You can see that I’m getting in closer, moving towards something that can be external, or it can be that I suddenly understand – internally – what I can do with this picture. I’m seeing something that I’m trying to get into the frame. In general I don’t make it. Every once in a while, I get there.

What else does the 35mm offer over, say a zoom, when working in the street?

Why a 35mm? Well, first of all, I happened to have a 35mm lens when I went to Europe and first started taking pictures. The stuff you get used to when you start out often stays with you. But it turns out that there are better reasons. The 35 allows me to get in very close to people, and I like that, but also, when you’re using a fixed lens you know where the walls are, you know? And I like the fact that a 35 is not a normal lens (it’s heading in the wide-angle direction), but that it feels normal.

The composition of a picture is more difficult to set up, I think, with a zoom. Somehow it feels like there’s more of a flow when you’re working with a fixed focus lens because you know you have to get everything right in the viewfinder – that is, unless you’re going to crop the picture, which I don’t do.

Why don’t you crop images?

When I began with photography and started looking at pictures by Cartier-Bresson and started reading a little bit, there were certain rules that were implied or even explicit. One was: don’t crop your pictures… I was a young photographer and that sounded like a rule, and so I followed it.

I think that was pretty stupid looking back on it now. I mean, why follow rules? Maybe you can follow rules, but it’s better to follow rules that you believe in, and it wasn’t that I believed in it, it was because that was the rule.

With that said I’m really glad, because by following that rule I was able to discipline myself. I learned what would make the picture really work. It meant I couldn’t get rid of stuff I didn’t want in the frame after I had taken the shot, I couldn’t crop, I couldn’t move things around in Photoshop. Obviously, when I began to take pictures people didn’t think too much about photoshopping, but you know what I mean.

I want an intimate connection with the reality that I’m photographing. I don’t want any phoney things happening, because that’s too easy. If you’re going to photoshop a picture, take a guy from one picture and stick him in another one, or take the guy on the left and put him on the right, take a woman and make her a man, whatever, anyone can do that – well, you’d have to learn how to do it in Photoshop, of course – but you know what I mean. That doesn’t mean anything to me, it’s easy – even if it’s technically difficult – it’s easy.

The difficult thing is to take reality and somehow make something out of it that becomes meaningful, without manipulating it artificially.

"I prefer the difficult path of finding unexpected things and wrestling them into a meaningful drama in the viewfinder"

- Richard Kalvar

So the challenge is what makes photography rewarding, especially in terms of making difficult images work?

I find it very hard to take a picture where everything works: all the elements, major and minor; their relationships to each other and to the rectangle and its walls; the implied narrative and its mysteries. How much easier it would be to set the scene up, to choose the people, to tell them what to do. Or to unite various elements from different images via Photoshop. Or to be satisfied with things that don’t really work. But the real interest of photography, for me, lies in the tension between appearance and reality. If you manipulate the reality there’s no more tension. The picture loses its force and its credibility.

I prefer the difficult path of finding unexpected things and wrestling them into a meaningful drama in the viewfinder.

I’m a great believer in things happening naturally in terms of how my own style developed. While I made the conscious decision not to crop pictures, I didn’t decide how I was going to photograph and what my style was. It wasn’t a decision, it was a natural, unconscious outgrowth of my feelings and my thoughts. I think that’s really important. You know, it’s who you are coming out and not who you decide to be coming out, at least in my case.

People are, somewhat unsurprisingly, a common point of focus in street photography. You have spoken about the allure of people in conversation before.

There are conversations every day and everywhere, and most of them are not going to lead to good pictures, but I’m curious, I’m a little bit of a voyeur, I have to admit. That helps if you’re a photographer. So, I like to go up and listen to what people are saying, even though I’m not recording it.

I’m intrigued by it. And then sometimes a conversation starts to get interesting; the way people are talking to each other, the gestures they’re making, the facial expressions, how they’re looking at each other or how they’re not looking at each other changes. At that point maybe I’ll start taking pictures and in general the pictures are not great… it’s just people talking to each other. But then every once in a while I catch onto something.

I have to be lucky to get a good picture. But what I can say that I do, after a lot of experience, is to try to maximise my chances of getting lucky.

How important is tenacity in making good work on the street?

Often you take a whole bunch of pictures and you find you haven’t solved any problems, you haven’t gotten to a place where you have a good picture. But if you hadn’t been taking a number of pictures, if you hadn’t been trying to work something out, then you could have missed the right moment. Keeping at it is essential.

Sometimes when I see young people, I say, how many pictures did you take of this thing? You know, it’s not a very good picture. They say, one. Or two, or four. I say, why didn’t you take 12 or 16 or 32? They had a situation that had potential, but they didn’t make anything out of it. They gave up before they even got started.

Every once in a while, I take a whole bunch of pictures and it was the first picture that was the right one, but that’s pretty rare. More often, it’s closer to the last picture.