Three Perspectives on Ethics in Image-Making

Following an Ethics and Images Study Day at Tate Britain, three industry experts reflect on questions raised by participants

In March, Magnum Nominee Sim Chi Yin – alongside Hilary Roberts of the Imperial War Museum and photographer and educator Anthony Luvera – led a study day at London’s Tate Britain on the topic of Ethics and Image-making. Here the three speakers reflect on areas of questioning raised by the study day’s participants over a number of question and answer sessions, focusing in turn on representation and aestheticization in documentary photography, the curation of conflict images, and questions around collaborative practice.

Sim Chi Yin

Magnum nominee Sim’s practice integrates multiple mediums including photography, film, sound, text and archival materials, as well as performative readings to explore projects dealing with issues of history, memory, conflict, migration and their consequences.

What are some of the ethical issues you have dealt with in your own work, and where do you think the field is on ethics at present?

Questions of ethics in their multiple forms are ever-present for any photographer working in the “concerned” realm — whether in documentary or non-fiction, journalism or in art, whether the work is made for reportage, the press, or a museum or gallery. As I titled one of my presentations in the Tate Study Day, I’m “guilty as charged” — on matters of representation, intervention, aestheticization and censorship.

The question of representation is often on my mind when I’m researching for a project and before I begin making the work. I ask myself: is this my story to tell? How am I portraying this issue, these people, this place? There aren’t always easy answers and one still has to make split-second decisions sometimes while in field, but one does one’s best.

As for the golden rule of “do not intervene (with the scene)”, I broke it 100 per cent when I worked on the story of “Black Lung” disease in China. I documented what turned out to be the final three years of the life of gold miner He Quangui, and became more than a fly on the wall in his home in the remote mountains of Shaanxi, got very personally close to him, his wife and their son. Six months into the project, his wife called me in tears at 4am one day and wailed “He’s dying, you have to help him.” I raised funds through a Chinese NGO, flew out there to pick him up, took him to hospital, and was his secondary caregiver for a tearful and harrowing week in hospital as his wife could not make the trip there. That’s intervention… one that helped him live another three years. I thought “human being first, photographer second”; and if we’re purportedly trying to bring about social change for the community we’re documenting and when faced with the task of helping one of them, we didn’t do it, it’s unconscionable. I was then open about the fact that I’d intervened, with editors who were interested to publish the story or curators who were keen to exhibit the work. I spoke openly about it in interviews too.

One of the biggest changes for me when I quit a decade-long career as a writing journalist and foreign correspondent for The Straits Times to become a freelance documentary photographer focused on long-form, self-directed projects was that I could choose not to be “objective”. In a newspaper, there’s the notion of impartiality, of being objective, but in doing long-form documentary work of my own, I’m following an issue or a person/subject for years because I care deeply about it, or it makes me mad, or upset, and I have something to say about it — and not necessarily to represent all sides of it. I don’t strive for “objectivity” even if I try to be fair (at least in text). Just our presence as documentarians changes reality. When photographers (including Don McCullin whose retrospective at the Tate this Study Day was organized around) talk about being a dispassionate observer just bearing witness, I understand what they mean, but looking at it with a finer lens, it’s not really possible in reality. Any sort of representation is subjective anyway… the minute you raise the camera, there’s manipulation involved — but that’s a topic well covered by scholarly critics of photography!

"Aestheticization — an old chestnut that gets thrown at photographers and photography. We make bad things look “too beautiful”"

- Sim Chi Yin

Aestheticization — an old chestnut that gets thrown at photographers and photography. We make bad things look “too beautiful”. In making my series “Most People Were Silent” on nuclear landscapes of North Korea and the United States, the choice of mood, color palette and an overall aestheticized look for the images was intentional. I got an email from a collector asking, “How does it feel to make something so horrific look so beautiful?” My reasoning is that if the aesthetics are a hook, a way in to opening a conversation on this highly-polarizing, tired issue, then the work does something. If I’d photographed nuclear victims’ burnt skin, deformed babies etc. yet again, I doubt people who were pro-nuclear in the first place would contemplate stepping into the gallery from the get-go. I don’t have the answers but am experimenting with different strategies of speaking to people across the divide — and I think we need ever more of that in these polarized times — rather than shutting down the conversation before we even begin.

Overall, it seems to me there’s a lot of concern over issues of ethics in our field in recent times. Ethics cover such a broad range of issues, across the making of images, their distribution and their consumption. In the documentary genre, the aspects that seem to generate most concern of late are: representation and the lack of diversity (in both photographer and the photographed), manipulation in the process and post-production of images, for instance. In the case of diversity — in gender and geography — and how we represent the “other”, I think the industry is very conscious of the need for change, but we might still have a long way to go… Apart from those concerns, the other issues are not new, even if there seems to be more buzz about them. These often stem from the “truth claim” of the photograph. On manipulation, I think setting up pictures — and passing them off as found moments — is much more difficult to find out than post-production manipulation for which there is forensic tools. There are rules out there like the World Press Photo’s which try to police what’s allowed or not. I think those rules try to set some sort of benchmark for that genre of work. Documentary forms themselves have evolved and some would say setting up or manipulating the imagery gets us closer to the truth or more evocative of the intended emotion, action or social change. I think that’s all ok and we do need to evolve to find forms that better represent our changing world; just be open about it. If a photographer still wants to submit their work for competitions like World Press or distribute their work for reportage use, then those are the current rules that the industry broadly holds on to. But one can always opt out of that award system (which is itself not unproblematic) and those methods of distribution. One just needs to be honest and transparent about one’s intention and process, and also choose the appropriate distribution channels for one’s work.

Issues of ethics in image-making touch us all these days as we live in a highly visual culture. Whether we’re makers, distributors or consumers of images — and we today often play at least two of those three roles — they were ever-present and call on us to reflect more deeply on our actions and choices.

HILARY ROBERTS

The Imperial War Museum’s Research Curator of Photography, Roberts specializes in the history of war photography, the history of modern conflict and the management of both analogue and digital archives.

To what extent has a growing popular awareness of issues of ethics in photography changed the way that curators and museums approach the handling of challenging images today – especially relating to images depicting conflict and violence?

An awareness of ethical issues in photography has always been required of curators and institutions wishing to engage with challenging images, regardless of the genre, style or purpose of such images.

Ethical questions, revolving around distressing images and issues of authenticity, were first raised amongst curators in the mid-nineteenth century. They also confronted the basic curatorial conundrum: how to evaluate the essential purpose of a photograph (whether it be to bear witness, to serve as an art form or do both simultaneously) and interpret it appropriately for the benefit of the audience.

These questions have been revisited regularly ever since, in response to events and new developments in the medium. The conflicts of the 19thand 20thcenturies did much to enhance awareness of the complexity of ethical issues associated with photography. Curators also realized that the passage of time can raise new concerns about historic photographs and that images which are not obviously challenging may also present dilemmas. An acute awareness of the broader context – social, cultural, political, commercial and technical – within which images are created and disseminated is therefore essential for any curator and always has been.

Digital technology and internet publishing have changed the ways in which the world perpetrates, experiences and observes violence. It has also changed photography and the way in which the public engages with the medium. Established commercial models no longer apply, creating new pressures for photographers and publishers. The speed and flexibility of these technologies have created new opportunities to bear witness and create art but have made it harder for audiences to evaluate images. A heightened public awareness of ethical issues has been the consequence of these changes.

In response, curators and institutions are becoming more open and transparent in their handling of such issues; communicating the rationale behind curatorial decisions and interpretation more clearly to their audiences. Professional standards and guidelines for museums and curators who work with photography are now published more widely and are reviewed more frequently. Regardless of the frequency with which institutions and curators engage with photography, it is imperative that they maintain a current awareness of associated ethical issues and communicate accordingly with the public.

Anthony Luvera

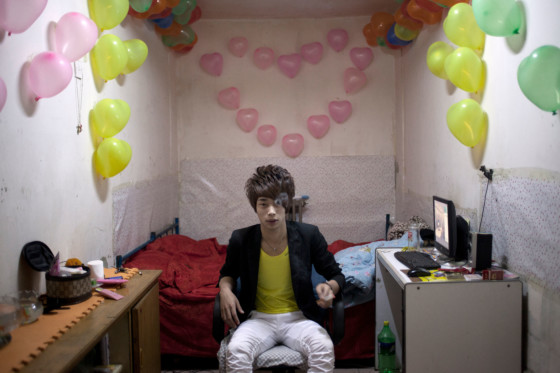

Australian photographer and lecturer Anthony Luvera’s work often exists within the collaborative realm – including his ongoing project on assisted self-portraits.

What is the point of collaboration, and how does a collaborative approach relate to issues of representation?

Photographers are storytellers. We speak about the world through the imagery we create. In doing so we hold power to shape narratives and influence preconceptions and understanding about the people, places and situations we depict. One of the ethical dilemmas a photographer has to contend with is speaking on behalf of other people, particularly when they have little or no first-hand experience of the lives of those represented. With this in mind, the use of collaborative methodologies to enable subjects to become active participants in the creation of their representation can be seen as an appealing way to seek a salve for the problems of representation. However, collaboration does not guarantee more ethical conduct, an honest approach, or more truthful work. So, what then, is the point of collaboration?

Inviting people to be participants, actively informing or co-creating representations of themselves, rather than passive subjects, can serve a number of purposes. It can enableaccess and insight into their lives and the habitat and the socio-political forces that shape their environment. It can enable rapport to be developed, trust to be engendered, and for the participant and artist to become familiar with each other. It can be used as a means to locate, infiltrate, observe, organize, consult, listen, and converse. Throughout this process, learning from failure, reflexive decision-making, reasoning, and adjustments can take place. By enabling the participant to develop technical skills to photograph and write about their lives, degrees of distance can be bridged by the artist and this can enable the artist to elicit more, or different, information that might otherwise be inaccessible or influenced by their direct presence.

One of the challenges of undertaking a collaborative practice is articulating the dynamic of the dialogical process and co-production that gave rise the creation of the work. That is, the time spent inviting people to take part, the conversation that ensues, how relationships are developed, how equipment is used, and how issues such as representation, consent, context, and authorship are addressed. There are no guarantees about the ethics or honesty with which the artist navigates these dialogues, particularly when a description of this process is provided without the contribution or inclusion of accounts by participants.

"As a symbolic act of emancipation that seeks to forge collective subjectivity, I would argue collaborative photographic practices do not enable a utopian negation of the problems of representation"

- Anthony Luvera

While the display of photographs and other materials created by participants may appear to give an unmediated or more authentic view of ‘reality’, what it effectively does is assert the subjectivity of the participant more directly in the artist’s representation of themselves as subjects. This affirmation of presence conjures a more resolute impression of ‘the real’ through the situatedness of the participant in a particular place and time, displaying their ‘having been there’, evidencing ‘this is how it was’. Handing over degrees of control, power, and ownership to the participant through the process of the creation of the work, a collaborative practice may be seen as a process in which ideological divisions between the photographer and participants are renegotiated. However, despite intentions to infer equality through a co-productive methodology, collaborative practices are unavoidably contained within a hierarchy. Distinctions can always be made between the artist and their participants, and dissemination of the work after its creation will largely be driven by the artist, albeit with degrees of consent and consultation with participants. Issues of agency, control, and power balance, cast a different set of questions for the outcomes of the work, and the accounts and documentation of the temporal processes that gave rise to its creation. What is the intention of the artist? How are the participants elicited and acknowledged? How does the methodology employed by the artist enable or limit the agency of the participant? How does the artist reflexively address their own assumptions, and challenge dominant preconceptions about the participant and the subjects of their imagery? Where does the artist disseminate the work, and how do these contexts affect the representation of the participant? How has the artist used models of documentation to make the questions, problems, constraints, and subjectivities explored throughout the duration of the practice explicit?

When considering the ethics and aesthetics of collaborative practices, rather than viewing the process employed by the artist as a means to uncover authenticity, reality, or truth, it is more productive to see collaboration practice as a way to harness and present a plurality of perspectives. However, as a symbolic act of emancipation that seeks to forge collective subjectivity, I would argue collaborative photographic practices do not enable a utopian negation of the problems of representation inherent in the act of speaking for another.