Telling Stories: the Single Image vs. the Series

How can you capture a story in just one image, and how does narrative unfurl in a long-term photographic project? Patrick Zachmann and Matt Stuart weigh in

Magnum Photographers

The difference in the practices of Magnum photographers traces right back to the agency’s founding: Henri Cartier-Bresson was the artistically inclined street photographer; Robert Capa the archetypal photojournalist; George Rodger the tireless traveller; and David ‘Chim’ Seymour concerned himself with humanitarian causes. This respectful difference of interests and opinions continues to define the diverse approaches of the current active Magnum membership. This was brought into sharp relief during a recent talk at the Barbican as part of the Magnum Photos Now series of events. In a discussion chaired by acclaimed writer Geoff Dyer, Magnum photographer Patrick Zachmann and Magnum nominee Matt Stuart deliberated their diametrically opposed positions on the use of a single image or series of images as a tool for storytelling in their work. Here, we present their reasoning for preferring each of their approaches.

Matt Stuart

Quoting Magnum co-founder and street photography forebear Henri Cartier-Bresson, Matt Stuart explained what underpins his approach boils down to the following words from Cartier-Bresson: “Sometimes there’s a unique picture whose composition possesses such vigour and richness and whose content so radiates outward from it that the single picture is a whole story in itself.”

Stuart explained, “I’ve spent the last 20 years or so walking the streets of London hunting the single image and the only thing that links these single images together is the place.” Examining some of his own best-known photographs, Stuart explained how single images of his contain a depth of narrative.

"There’s often one picture that I find that you can pull from something if you absolutely have to, and my daily grind is to try and get one picture from the day of what actually happened."

- Matt Stuart

“Sometimes, especially with street photography, stories can be implied, and in this particular picture I think there’s an interesting collision between these two people. There’s a man who is pretty evidentially lost in the foreground, and you can tell he’s lost due to the fact he has a map, he’s on the telephone and he’s covering his mouth. Body language is something that I’m quite interested in and something that I look at a lot when I’m out on the street, so I realize when people appear to be lost. The two young men behind him know exactly where they’re going, or at least that’s the implication because one of them is pointing confidently. The difference between the two has made this strange swirl of gestures of two men who know where they’re going and one man doesn’t.”

Even when taking on more traditional reporting commissions, Stuart is still drawn to creating images that, within them, capture an entire story. The Grenfell Tower fire and the London Bridge terror attacks both provided Stuart with the challenge of capturing the complex and emotionally charged narratives of difficult events. Discussing the images he shot on the morning that commuters returned to work on London bridge after the terror attacks on June 3rd, 2017, Stuart pounded the area with his camera, searching for a shot that, for him, summed up the mood of the city on that day:

“I decided to get up very early in the morning and go to London Bridge. I was there at 5 o’clock in the morning; I was looking at people walking along the bridge and coming to work, and at about 8 o’clock, which I know is a busy time on London bridge, I saw a woman walking with a Union Jack in her bag. It was just the stick poking out, and I thought, ‘That’s strange that she is walking with a Union Jack in her bag,’ so I followed her, which is something you do a lot as a street photographer, and took two frames that I find interesting. I found her very relevant to the day. In another moment she pulled out the flag and just walked across this bridge with it, so there’s two images with different moods – one potentially positive and one more sorrowful.”

For Stuart, these moments of kismet represent often a whole day – or even longer – of leg work. Returning to the words of Cartier-Bresson, Stuart says, “There’s often one picture that I find that you can pull from something if you absolutely have to, and my daily grind is to try and get one picture from the day of what actually happened. Working in Magnum and having more of a drive to get the picture than ever before, I find that I am getting pictures quicker and I’ve learnt to be a better photographer already.”

Patrick Zachmann

Identifying more with photographer and filmmaker Raymond Depardon, and with the deeply involved and decade spanning work of immersive and nomadic photographer Josef Koudelka, Patrick Zachmann’s approach is the polar opposite of Stuart’s. Zachmann takes a long-term approach to building a story, and his curiosity for his subject guides his exploration, incorporating cinematic ploys in his documentary work, interwoven with narrative strands of fiction. It is through getting to know his subject matter over a long time period, and entering into it from multiple angles and perspectives, that Zachmann’s multi-layered storytelling comes through.

Speaking at the Barbican event Zachmann said: “I’m not like Matt Stuart but I really like his work as a street photographer. I have never identified with street photographers. From the beginning, my commitment to photography is to tell stories – about the world, about others, and about myself and my own family, often through that work.” For example, Zachmann’s long-term study of Chinese diaspora has proved a vehicle for him to consider his own family history. “I am very often asked if I consider myself more a photojournalist or an artist and I have never been very clear on my answer, and I’ve recently come to think that I am both,” he said.

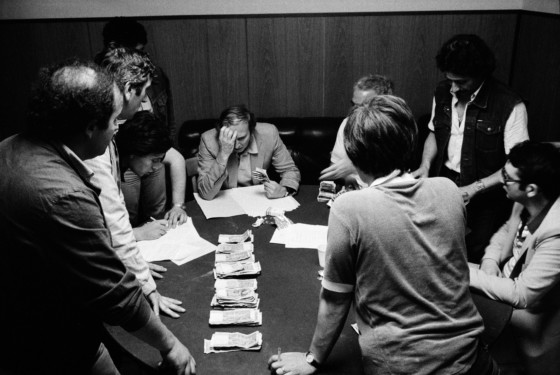

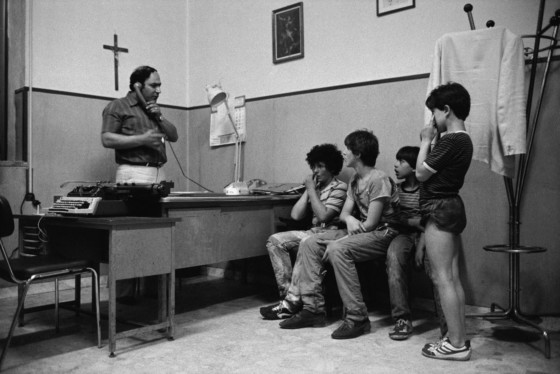

One of Zachmann’s earliest projects to bring him acclaim was his work on the police and mafia in Napales. Originally inspired by a small newspaper story that caught his imagination, the project led to a collection of cinematographic photographs that became his first book Madonna! in 1982, which was accompanied by a fictional novel inspired by the experience, and illustrated with the images, published a year later.

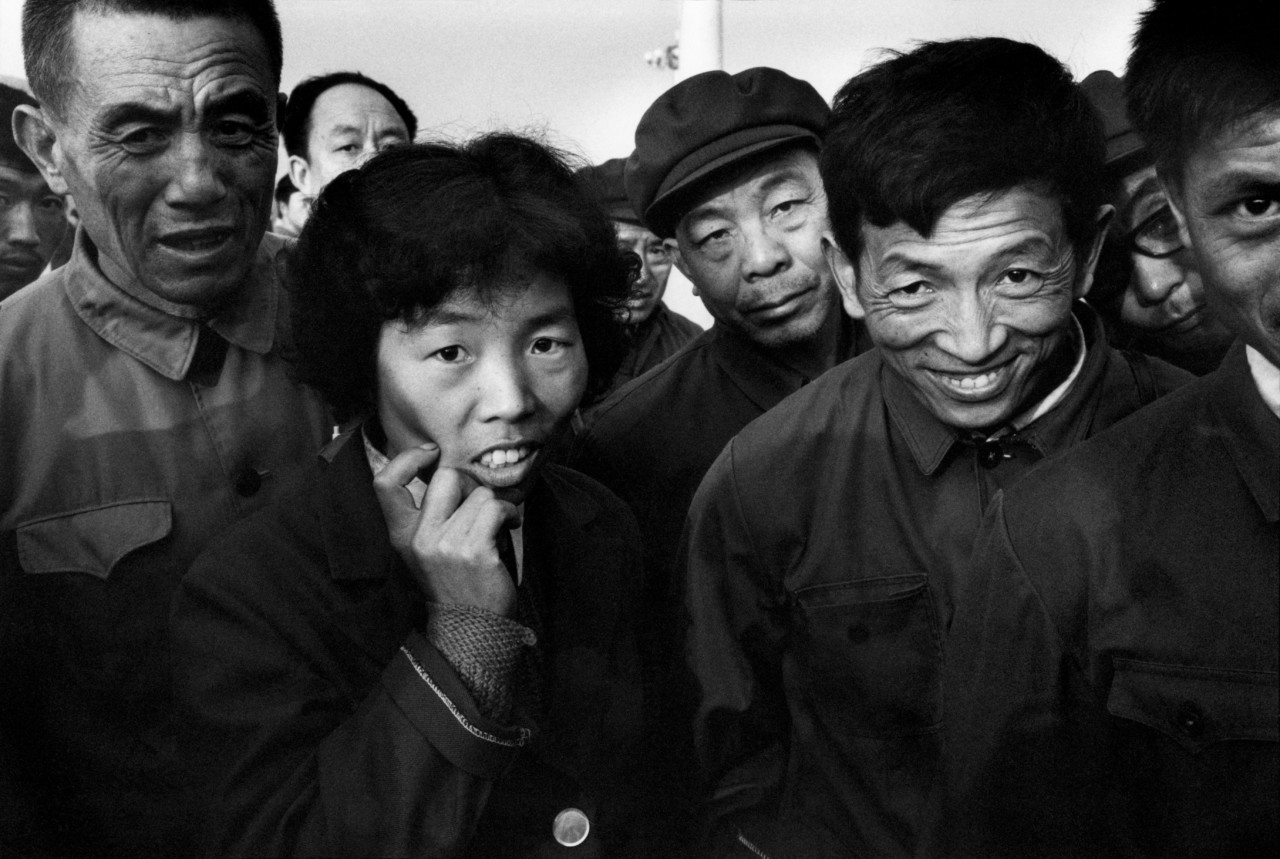

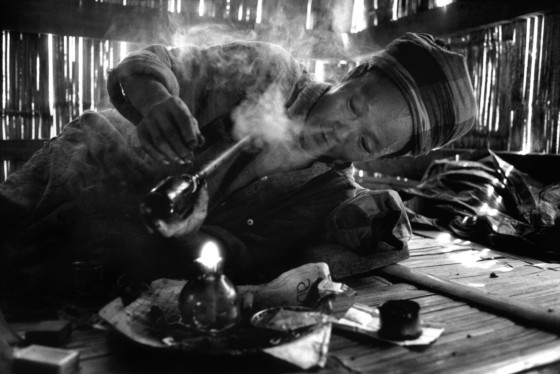

Around this time, Zachmann made his first trip to China (1982), which he would return back to over the decades that followed. His interest piqued and stylistic approach inspired by Shanghai film noirs of the 1930s, Zachmann’s study of China led him to the underbelly of the city.

"I am very often asked if I consider myself more a photojournalist or an artist and I have never been very clear on my answer, and I’ve recently come to think that I am both"

- Patrick Zachmann

"When you’re a journalist you cannot be led by your unconscious or by interesting light or faces, but you have to look for information"

- Patrick Zachmann

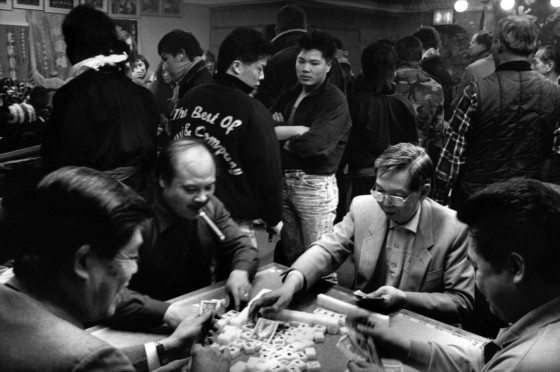

“I really found a love for these movies, which were dealing with the underworld of the Triads – the Chinese mafia, secret societies, prostitution and illegal gambling; all these things interested me as a photographer, visually. Then, when I started my work on Chinese diaspora and then I continued working in China, I realized that, consciously or unconsciously, I was inspired by this images. Actually, I was looking for these images in my unconscious. That’s also what I think makes the difference between a journalist and an artist. When you’re a journalist you cannot be led by your unconscious or by interesting light or faces, but you have to look for information.”

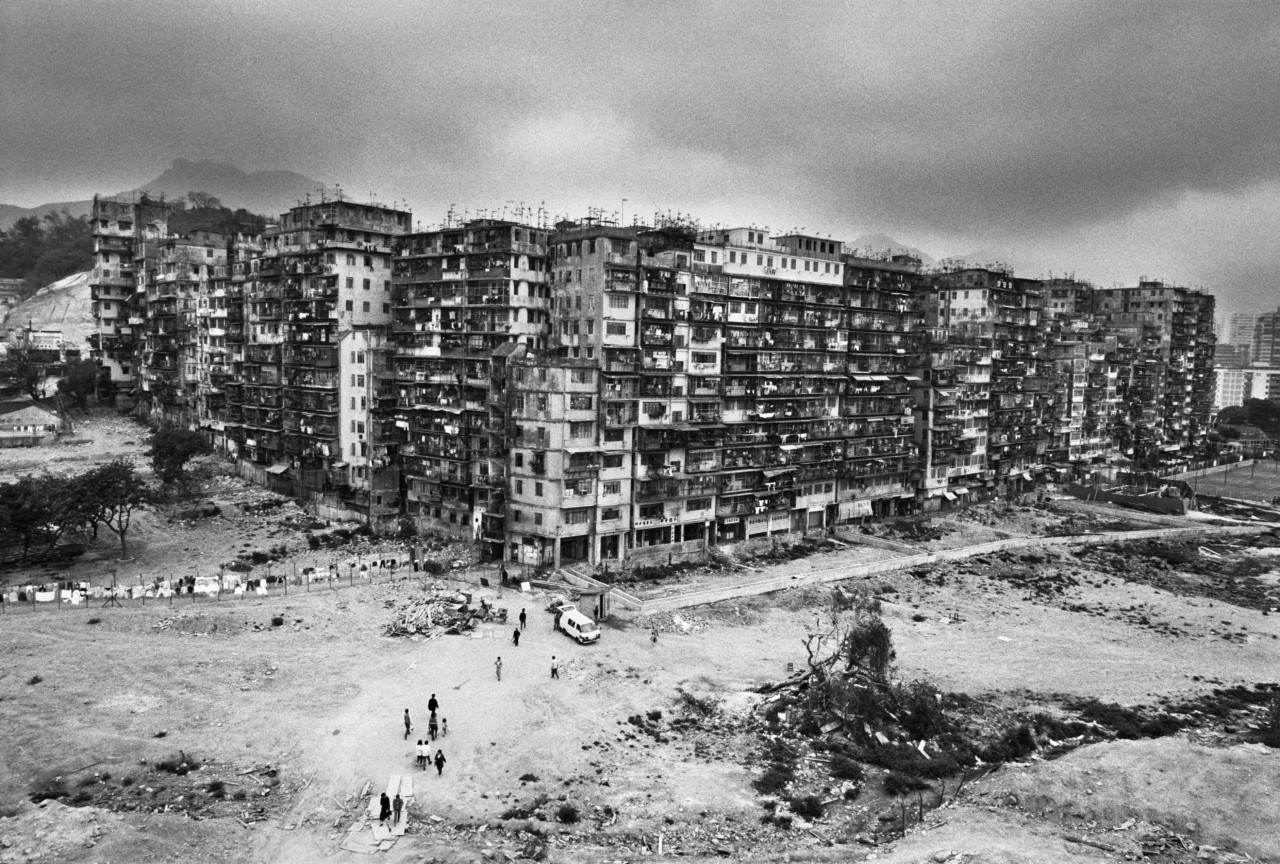

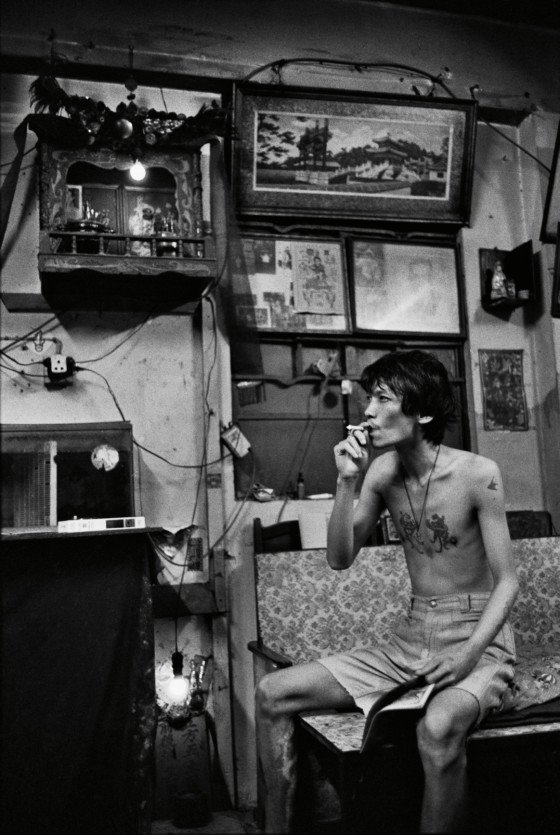

The lure of the dangerous side of city life drew Zachmann to the now long-gone “Forbidden” or “Walled City, a lawless area in Hong Kong that belonged to mainland, communist China. Access was gained through a nervous guide, who Zachmann met during a three-month trip through Asia is referred to only as “W” in Patrick’s seminal books W. Or The Eye Of A Long Nose and So Long, China, “because he was a very mysterious guy and we never knew who he was.” With W’s help, Zachmann photographed the dark world of the Walled City. While the sun shone hot outside, within the rabbit-warren of the complex it was dark and dripping like rain.

"Behind the pictures, I usually also have stories, which I then publish in my books"

- Patrick Zachmann

“Behind the pictures, I usually also have stories, which I then publish in my books,” he says. “When I travel I take a diary and I am often writing during the trip.” Zachmann’s long-term approach provides context to complex stories that may be missed or misinterpreted in the single image. Zachmann was photographing Beijing youth in 1988 to 89, and while many of the most well-known images from this era are those of the most dramatic crescendos of protest, Zachmann captured images of the Tiananmen Square protests at their beginnings, while there was more of a festival feeling. In fact, Zachmann describes it as a “Chinese Woodstock.”

“I arrived in Beijing, I could see groups of people gathered in Tiananmen Square from my taxi, which if you knew China, was very unusual, so I went there and witnessed what was the very beginning of the Tiananmen Square protests. I stayed almost the whole night with the students.” At this point Zachmann switched back into photojournalist mode, but still stuck to his signature style of shooting in black and white with a Leica.

However, having already spent a great deal of time understanding Chinese culture from various entry points, Zachmann’s understanding was, at this point, arguably much more nuanced than the foreign press who flooded in to document the growing unrest. “Most of the reporters, who actually were going from one conflict to another, didn’t understand anything because they didn’t know China, they didn’t know Chinese culture, the codes,” he said.

“Tiananmen Square before the crackdown was like a festival, it was like something absolutely exceptional, full of hope. Years later a Chinese friend of a friend told me he will never forget that time because he was there with his girlfriend, and it was the first opportunity he had to spend the night with her. For reasons such as that this aspect was very important, but isn’t something that was really covered by the media that was there.” It was arguably Zachmann’s long-term investment in Chinese culture that allowed him to photograph moments that may have seemed inconsequential to international press but were hugely significant to Beijing’s youth.

Read tips on working on long-term photographic projects here.