The Lost Head & the Bird

Sohrab Hura discusses the fluid interplay between photography and film, and channeling the growing chaos and absurdity of life in India in his work

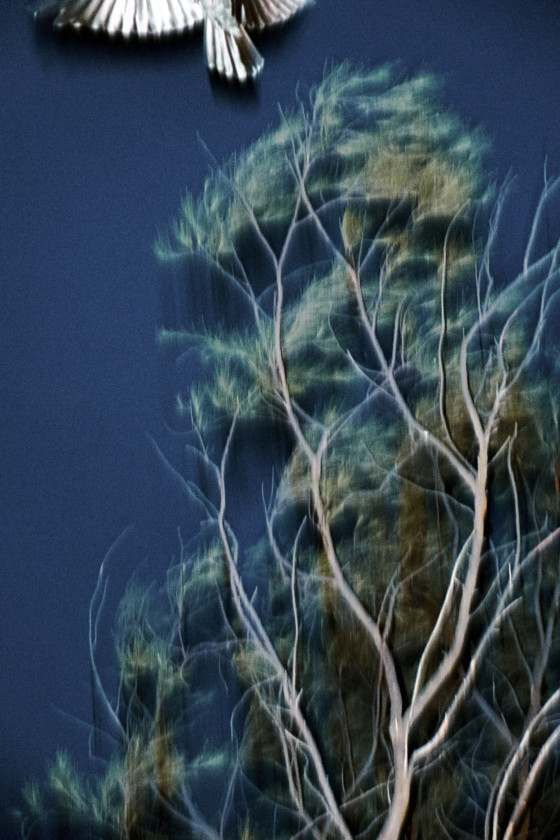

Sohrab Hura’s project The Lost Head & the Bird uses India’s coastline as a lens through which to re-examine the nation’s changing politics, and society – the growing and pervasive sense of caste, sexual, religious and political violence. The project, accompanied by his unnerving short story of the same name, morphed into a new short film. Here, Hura discusses the advantages of moving image, the use of sometimes brutal found imagery, and his working process.

Can you explain how this project started, and some of the ideas behind it?

Around ten or fifteen years ago I had started to sense a growing murmur of dissonance around me here in India. It didn’t seem as explicit back then and was more an undercurrent. It was in the way people talked, their body language, the gaze, and behavior in general. I couldn’t really put my finger on anything specific, but an uneasy feeling always lingered.

Maybe as India’s economy had started growing in the late 90s into the early 2000s, a certain sense of pride seeped into people, which became more aggressive with time before turning into the rabid nationalism, accompanied by violence, we see today. By 2013 the build up of all of that had become extremely heavy. I couldn’t help but want to spill out my reaction to it. At that time there was already a visible shift towards this new vitriolic socio-political landscape that had been exacerbated by the current political disposition. Everything had started to feel unreal and absurd because of the extremities of polarization and violence and also the silent habituation of it – it had started to affect the way I photographed.

When you first published this work, it was accompanied by a short story you wrote – a strange, eerie, and slightly unnerving story. Why was it that you felt this the best accompaniment to the work – does it tie into that absurdity you mention?

What I was trying to photograph was a pulse of the world that I was living in, here in India. That was something I could only allude to and not straitjacket down into something more definitive. Giving a straightforward explanation of the project would have removed all other possible entry points into the work. That would have negated everything the work is trying to do in the first place, which is to take the audience to a place out of doubt, because that is the situation today – we don’t know what to believe or not.

So, I created that short story which could live alongside the photographs as its own being, and build toward a specific atmosphere, along with the photographs. The story in its metaphors is political and concerns characters at different ends of the power structure where that hierarchy is defined by gender as well as a dependence on superstition and religion. Madhu, the main character, has had her head stolen by her past lover out of spite because he could not have her to himself. She is lonely and gives in to trusting this fortune teller who repeatedly takes advantage of her not being able to see by selling her a crow telling her that it is a parrot with a horrible cough. An ‘idiot photographer’ also passes through the story. He wants to photograph ‘the woman without the head and all the other wonderful and vicious things he sees along the coastline’. Today that boundary between voyeurism and active participation is more blurry than ever. You and I both are that ‘Idiot Photographer’.

The story itself gets caught in this never-ending loop when it finishes with the woman going back to the fortune-teller to – again – buy a crow thinking it is a parrot. This text part of the work allows me to open up spaces that wouldn’t have been possible if I had written something more informative and led by the images.

"Everything had started to feel unreal and absurd because of the extremities of polarization and violence and also the silent habituation of it - it had started to affect the way I photographed"

- Sohrab Hura

Was the work shot in a specific area, or focusing on a particular social group? Or is it as open and ambiguous as your text suggests?

The work is not about any specific region or people. I mean, it’s all in India and I travelled to different points of the Indian coast to find my material, but I’m not trying to make the work factual in any way. The work was initially called The Coast, but the coast was always about the edge, the periphery, the margins, a sort of a tipping point.

The actual coastline that I photographed was just a window into this psychological landscape of the entire region which this presumably calm border of a coastline holds together. I think of the work as a balloon which I keep blowing air into. What one sees is the surface of the balloon that keeps inflating. At some point if I don’t stop blowing air into it, that balloon will burst, but what I want to do is to try to take you to that point from where you start to sense that that balloon might burst at any moment. That point that is my place of interest.

The literal coastline of this country that I’m using in my work is only that surface of the balloon. But the work is actually about all that air being pumped into that balloon and that point where one might sense that the balloon might burst.

"I had been experimenting with a specific paired sequencing of images, or diptychs. I like to imagine that the photographs in that sequence are able to move forward in this way - like the way we walk - with one leg following the other"

- Sohrab Hura

How did this body of work move toward being a film? Was that always in your mind or something that developed after-the-fact?

I don’t really plan on anything when I start working on something. In the beginning I need to feel my way about in the dark and to make sense of the world that way. Once the work has some body to it then the ideas and plans start to seep in and the work starts to morph into different forms with all the back and forth I have with it over time.

I had already started working photographs into films a long time ago, so the form itself wasn’t new. In the case of The Lost Head & The Bird I had been experimenting with a specific paired sequencing of images, or diptychs. I like to imagine that the photographs in that sequence are able to move forward in this way – like the way we walk – with one leg following the other, with each new juxtaposition forming a new meaning.

In that simple paired sequence pace was never an affecting factor, but it was something that I wanted to experiment with. In 2016 my friend Wendy Marijnissen of Bending the Frame introduced me to two musicians – Hannes d’Hoines and Sjoerd Bruil – for a live performance with my work. That is where I first tried to move that sequence forward at an increasing pace to point where it was nothing more than a flicker and it worked quite beautifully. From then on, I started to build the work into a film where that spiraling would become a gateway to the last part of the film where I finally wanted to take the audience to. I continue to use a recording of that first live performance as the film’s soundtrack and Hannes and Sjoerd continue to extend their experimentations with their music along with the video in their performances. A lot of my work comes about this way, by just trying things out.

"There is this vortex of information where everything is getting mixed up and sometimes it’s difficult to discern what is real and what is not and so there is a need for a re-evaluation"

- Sohrab Hura

What extra aspects do you bring to the project with moving image, how does the format expand the photographs’ impact?

Hopefully the experience of the audience with the film is completely different as compared to just looking at the photographs in a book or as print. In the film I’m using my photographs to just create a path, to lead the audience into a space embedded in the real world. That space is made of videos and photos circulating on Whatsapp, Facebook, Youtube and other such social platforms; images spanning across pop culture, history, propaganda, protests, weird viral images, stupid and funny things trending online and all the way to images of violence that are in high circulation today.

There is this vortex of information where everything is getting mixed up and sometimes it’s difficult to discern what is real and what is not and so there is a need for a re-evaluation. The film is, in that sense, far more precise than the book – which I plan to publish next year – and I hope that it is only in the echo that one is able to step back into it and try and make sense of it. Where as in the book I’d like one to be able to step into the writing and the photographs as and when one wants to. There is more looseness and space for imagination in the book than there is in the film. The form can change the work completely and I love how malleable photography can be.

Your use of found footage – as you mentioned – leans toward some very brutal images. What’s the power and advantage of using that found footage?

I think all the material and information being produced out there, in the real world, that is so easily accessible is also scarily powerful. A lot of it gets created with no agenda, but agendas lie more in how that material is used. That is making the world quite scary, because control over information is completely slipping out of our hands. It was always an illusion that we had any control over information in the first place, but now we are just a lot more aware of that lack of control and its consequences are a lot more visible.

Some years ago my parents, being really new to social media like Whatsapp, would forward me messages that they thought were real news. To them those messages were at times a lot more real than what the newspapers or news channels had to say. That has been the one great success of the government here: a break downof the validity of the idea of ‘the press’, a system that could have potentiallyheldthem accountable. Instead, today we have a situation where at the behest of rumors engineeredon Whatsapp and Facebook people, who more often than not belong to minority communities are lynched by mobs and we are slowly being pushed into a state of a New Normalwhere somepeople have even started finding excuses to justify such occurrences. The film spirals into a maelstrom of all that collected imagery towards its end. That is me vomiting out of my brain all the information that I’m constantly getting bombarded by.

What are the rewards of working in photography and moving image simultaneously – do you find that your photographic practice develops alongside your film work, or do you see them as separate things?

I’d rather think in terms of images than photographs. Images can be still, they can be moving, they can be text and they can also sound. For me the possibilities are endless. Stills (photographs) are just a part of the larger idea of an image.

I only end up consciously separating between the photograph and the moving image depending on my intent. I think moving image made it a lot easier for me to play with time and pace and that helped in consciously bringing rhythm into whatever work I made. My first book Life is Elsewhere led to me making my short film Sweet Life and my last book Look It’s Getting Sunny Outside!!! was born out of that film. Likewise, there are films that I’m currently building that are affected by the stillness of a single photograph and that helps to break away from the narrative element that can burdens films.

So, each form can help affect the narrative engine of the other. But this movement across the different forms is organic and my expectation from each form is different.

The Lost Head & the Bird will be screening at the following events:

Berlin Atonal, on August 30.

HMKV Dortmund, throughout September.