The Public and the Private: Photography’s New Digital Territories

Magnum photographer David Alan Harvey, Magnum’s Digital Director Anne Bourgeois-Vignon, and Rory Blain, the director of digital art platform Sedition, discuss how the digital space has altered our ideas of privacy and ownership of the still image

Does a private act of viewing an image become a public one when you click the like button? And how much has our drive to tell a public audience our stories changed since the days of talking by a campfire? These questions and more were discussed by Magnum photographer David Alan Harvey, Magnum’s Global Digital Director Anne Bourgeois-Vignon, and Rory Blain, who is the director of Sedition, an online platform for buying, selling and collecting digital artworks by world-renowned artists, such as Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst, and now a curated collection by Magnum Photographers. In a Magnum Photos Now event at the Barbican in London, chaired by artist, writer, and curator Aaron Schuman, the speakers discussed photography in the digital space from their own perspectives, often relating back to the complicated relationships we have with photography. Here, we present some of the key issues that were touched upon.

"What’s interesting about the transgression between the public and the private is that it probably creates a bigger distance between the things that are actually private and actually public"

- Anne Bourgeois-Vignon

Paper vs. Pixel

“The relationship you have with a book, when you’re sitting in the chair or in bed with a book in your hands is a very similar experience to an iPad or a laptop, in terms of the intimacy, and yet, it doesn’t seem to fulfill the same thing,” states Aaron Schuman, comparing the solitary pursuit of scrolling through one’s Instagram feed to looking at a photobook – both private experiences, but yet one becomes public with the act of ‘liking’ the image. “What’s interesting about the transgression between the public and the private is that it probably creates a bigger distance between the things that are actually private and actually public,” Anne Bourgeois-Vignon adds.

Sedition’s Rory Blain offers some explanation as to why we still hold more reverence for the printed image: “A photography book offers you more context, whereas on an iPad, you swipe and that same space is taken over by another image, there isn’t the same contextual relationship in the way you would have in a book,” he says, also citing a study that found that you use a different part of your brain when looking at a screen from when looking at a page, even if that’s text. “It proves that you actually take in and retain information better from a non-digital source.”

The private made public

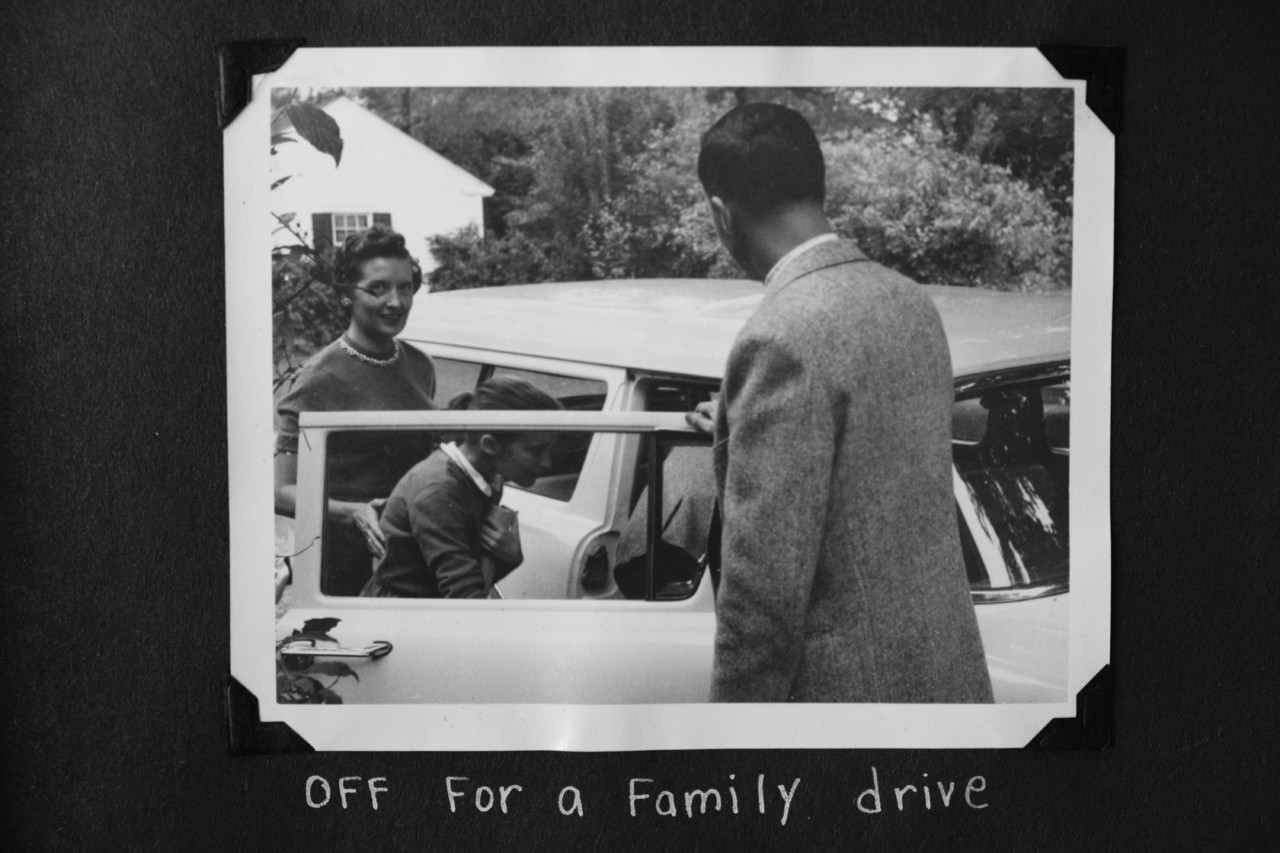

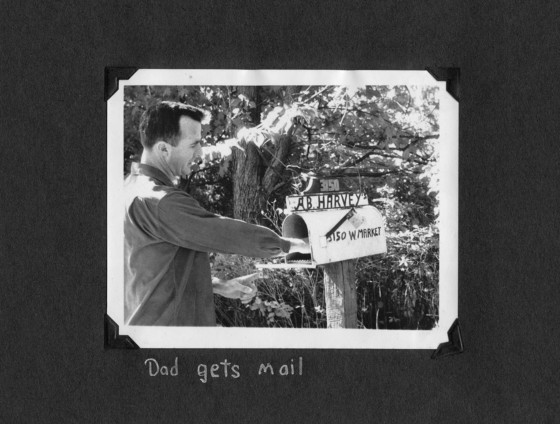

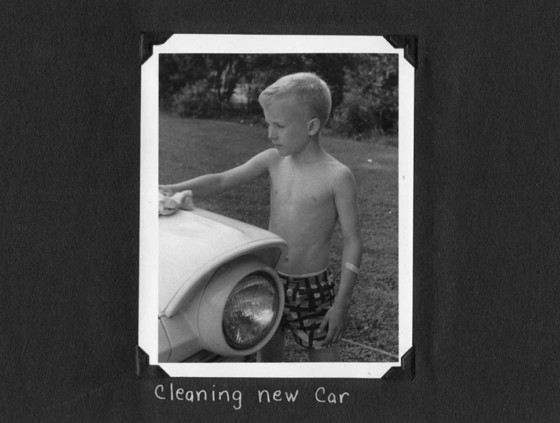

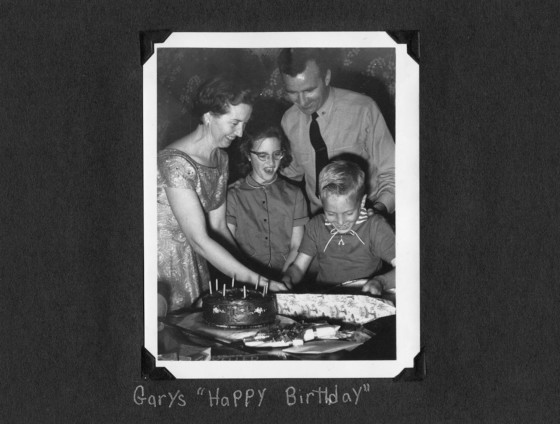

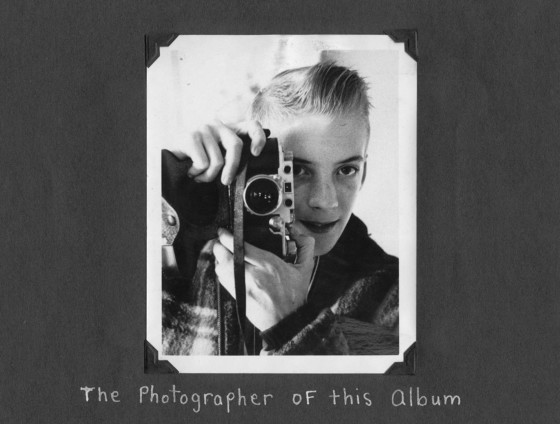

In a presentation about his practice, American Magnum photographer David Alan Harvey went way back to his earliest foray into publishing and sharing his photography. He bought his first camera, a Leica 3F, with his newspaper route money at 14 years old, and with it made Off for a Family Drive, for his grandparents. “Now I realize that it is my most pure work,” he said, “not influenced by anyone or anything; it was just for my family.” Although he says that even back then he approached the project as a professional, “I undertook it as a professional. I wanted to be a magazine photographer. At 14 years of age, I approached the project as I thought a professional magazine photographer would. I didn’t have a large audience – I dreamed of an audience. My audience was my grandparents.”

Magnum’s Digital Director Anne Anne Bourgeois-Vignon also touched on family photos in her presentation: “Vernacular photography holds a special place in our hearts, constitutive of collective identities and memories,” she said “If the family album is no longer in use, has it been replaced by the social media feed, and can the social media feed serve as a suitable replacement?” With moderator Aaron Schuman pointing out that, “all of these things, we do online now: the pinboard is made public, and the book for your granny has been made public.”

However this discussion raised the important point that because we are making public these previously private images, it’s not a simple move of just opening up images that previously would have stayed within a small audience to the wider public, but it actually creates a layer of self-censorship as we decide what to make public and what to keep for ourselves. “It actually creates a bigger gap between the public and the really private,” says Bourgeois-Vignon, and perhaps these personal images will never again have the purity of Off for a Family Drive.

The audience talks back

When sharing and viewing photography becomes public, so does viewers’ feedback. For viewers of the image this, as Bourgeois-Vignon describes, can be “fraught” as one decides what they should be publicly seen to be appreciating, or not. But for the author of the image, there is now the experience of receiving live, perhaps unsolicited feedback from anyone in the world, something that older photographers who began working before the advent of Instagram find novel. David Alan Harvey gave his thoughts:

“For me it’s a whole new concept: popularity and likes. I never had any idea what a mass audience thought of my pictures until the last five years, which is a very small part of the amount of time I’ve been taking pictures. I absolutely didn’t care. I was an art student – I did my thing and I never cared what anybody thought about me. I was happy to get a grant when I could get one. I cared what those people thought, but even then I really put it together in my own way. In fact, the thought of mass appeal was a negative in my art school; to be popular was absolutely not cool, so this idea of likes and popularity is a whole new thing, that I still don’t care about.”

The new campfire

Beyond the new avenues for feedback and conversation that social media brings, there is something incredibly “primal” about the sharing of stories to a collective audience, according to David Alan Harvey. The photographer has spent his career exploring African and Spanish culture and diaspora, and has traced storytelling in African culture to its pre-dating of the written word. He photographed the musician Jally, a kora player with rapper Omar in Senegal (pictured above) singing around a campfire on a beach: such is the way stories are passed down stories through generations. For David Alan Harvey, the digital space is a throwback to those ancient campfires.

“It’s something very primal, even more than we ever thought. It’s about community, it’s the campfire. This is the new campfire, and campfires are where you tell stories to a public. The public could be ten people when we were sitting round the campfire as kids, camping. It’s a larger community now. We’re consuming photography this way – and guess what, we want more, and more and more – we can’t get enough of it. It’s the need to be in touch with each other, and it’s still somehow a private experience, even though the pictures that I made for my grandmother are now going out to millions of people, they are still, in my view, a private experience, and you’re sharing it with a few more people that you used to.”

"This is the new campfire, and campfires are where you tell stories to a public"

- David Alan Harvey

A question of ownership

Another question that is impossible to ignore in this debate is that once images are made public, they are often assumed, wrongly or rightly, to be public property – how then might people own digital photography in the digital space in the way that they might own a fine print, which they’d display in their own personal spaces, homes, etc? Anne Bourgeois-Vignon pointed to a human drive to somehow own images, as she quoted Susan Sontag: “To collect photographs is to collect the world” for “they feel like knowledge… As photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people take possession of space in which they are insecure.”

“This desire to possess,” said Bourgeois-Vignon, “is part of our attempt to own a cultural space, in which a fragile sense of self-identity can be shaped, a performative space in which a relationship between the individual and their culture is born.” On Instagram people build that space through a curation of images they have taken or collected, but the idea of owning a digital image, having more rights to it than somebody else, is more complicated. Sedition is a service that fills this new space in the digital market for photography – allowing people to own digital artworks, of limited edition. “With Sedition, you’re taking something that is assumed to be public and you’re making it into a private commodity, but also a private experience, seen by a small private group,” said Aaron Schuman.

Sedition’s Rory Blain explained that the idea of digital media, particularly the idea of a limited edition of digital media is difficult, and explained how they make sure there is a limited availability to digital files. “Any artwork that is positioned on the site carries with it a digital certificate and a digital watermark,” he explained. The files are also protected with a square of pixels within each image, “which, in order to break down, you’d have to find each of those pixels and attach the code to it.” This allows the digital artworks and fine photos in which Sedition deals to be genuinely of limited supply.

Read about more discussions from the Magnum Photos Now events here.

A limited quantity of limited-edition digital Magnum fine photos are available to own through Sedition. “70 at 70” will see the two arts organizations coming together to present collections of iconic photographic and video works from Magnum’s archives, created over the last 70 years. The partnership will involve the collection of carefully selected works to be released exclusively on www.seditionart.com over the course of 2017, allowing collectors to be able to view and purchase works. Image makers are also invited to place their own works into the digital marketplace with Sedition’s Open Platform.