Three Graduates Discuss Crafting Photographic Projects

We explore the work of three photographers who participated in the 2018 Creative Documentary & Photojournalism course in Paris, developed in partnership between Magnum Photos and Spéos Photo and Video School

2018’s one-year program in Creative Documentary and Photojournalism in Paris was delivered by Spéos Photo and Video School alongside photographers and staff from Magnum Photos. Coming to a close in July 2019, the intensive course was aimed at providing students with the historical and contextual framework required to develop and engage in critical thinking about documentary photography, as well as providing technical guidance and tutorial support to develop individual documentary practices.

Magnum photographer Patrick Zachmann mentored the course participants, and selected three graduates to have their work featured on Magnum. Below, they share their experiences of taking part in the program and speak about the processes of crafting a long-form documentary project over the course of a year.

Zachmann shared the following thoughts on teaching the course:

According to me, the most important moment in the photographic process is, paradoxically, what happens before and after the shooting itself. This is because, if you haven’t given enough thought beforehand to your subject and who you are, you won’t get the best pictures or you’ll waste a lot of time trying to get the right situations. And if you don’t pay enough attention to the editing process, you may choose the wrong images. Editing is essential. That’s mainly what I try to teach the students.

I like the idea of transmitting my experience to the younger generation, helping them to find a personal approach to a subject, and working with them on the development of their own visual language. As a practising film director as well as photographer, I try to enlarge their vision and help them to structure the narrative of a story.

With the Spéos-Magnum course, being the photographer who follows up the students’ main projects allows me to witness their improvement over the course of the year, which is very exciting.

Tim Aspert – Being Angela

Tim Aspert’s project, Being Angela, was initially influenced by the 2018 murder of a trans woman, Vanesa Campos, in Paris. Sympathetic towards such public struggles, and thinking about personal acquaintances of his who do not identify in terms of binary gender, Aspert decided to document trans lives in an attempt “to testify to the trials and resilience that punctuate their journeys”. With help from a trans rights group, Acceptess-T, he met Angela, a Brazilian trans woman who had been living in France for five years. “Angela let me access her life with great sincerity,” he says.

“Struggles to live and to affirm trans identity are intimate and unknown. My project seeks to testify to the strength and universality which emanates from the battles engaging identity, which everyone should be able to express at their convenience.” He elaborates: “By documenting Angela’s daily life, by showing her body and her soul in these ordinary battles, it seems possible to me to raise awareness and advocate for people’s freedom to exist.”

Aspert says extended projects working with individual subjects can present creative challenges: particularly, interpersonal doubts and uncertainties. “I try to establish emotional bridges that translate my sensitivities through my subject, to express them in my photos, to create connection through emotion,” he says, “with patience, there is always something magical or unexpected that happens that can generate an encouraging picture.”

His ambitions are for Being Angela to continue in a published or exhibition format. “The project is written as it goes along, at its own pace. I experiment a lot, while fixing myself to certain protocols in order not to get lost on the way.” He continues, “working so close to someone is extremely enriching; it is an exchange, a fragile alchemy in which you give as much as you receive. Incredible links are created, within and around the project.”

The course was valuable to Aspert as it provided an opportunity for him to consider the motivations and approaches of contemporary visual practitioners: “to understand better why and how photographers [represent] the world today.” He has learnt the importance of the modes of expression that reflect our current era. After having previously worked mainly in black and white, Aspert became more aware of the roles that color, and experimental techniques with light, could play in visually translating his subject’s personality and environment. For Aspert, a piece of guidance from the course which has stayed with him, and which he now takes as his mantra, was Antoine d’Agata’s advice: “Follow your obsession”.

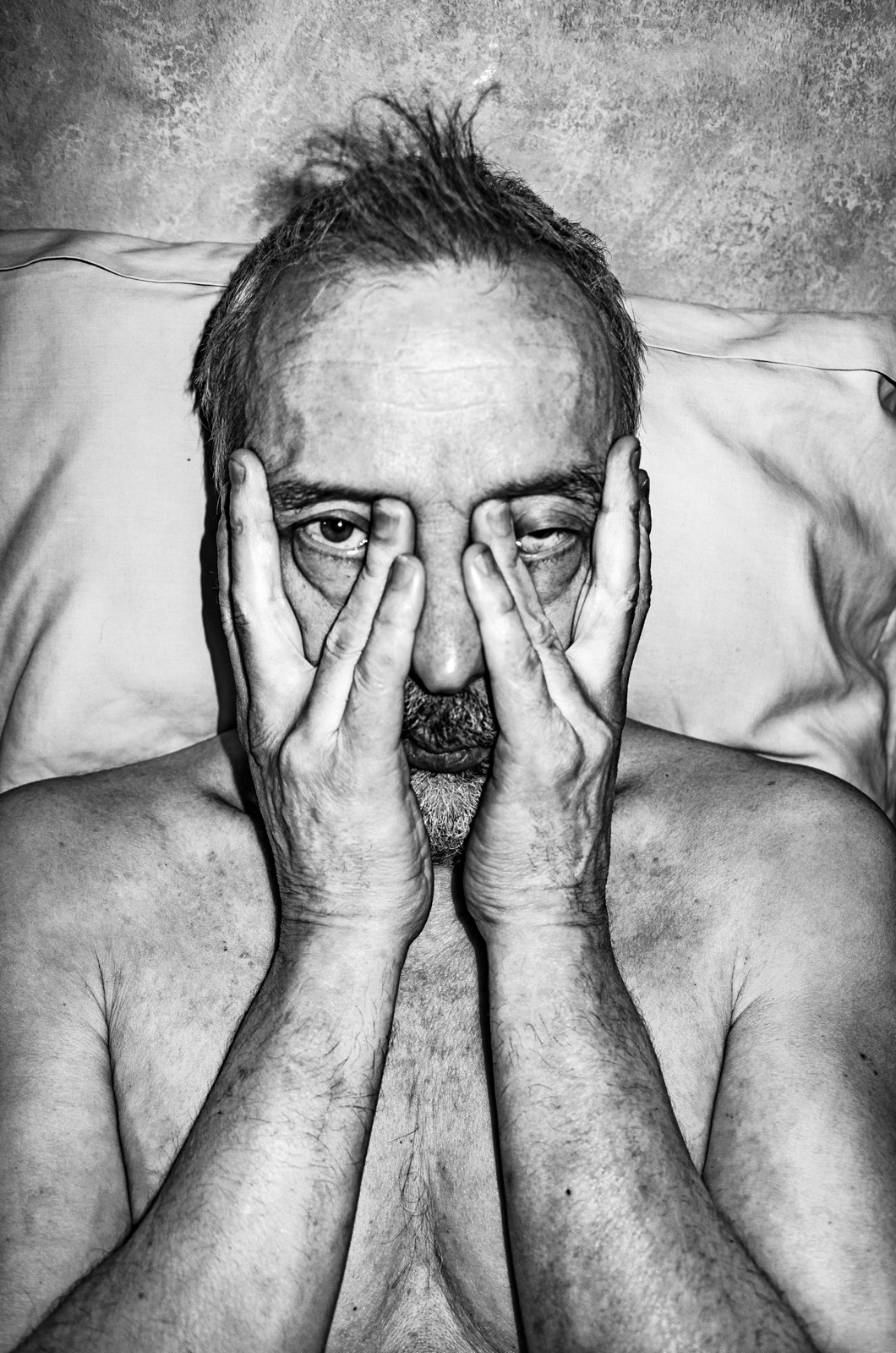

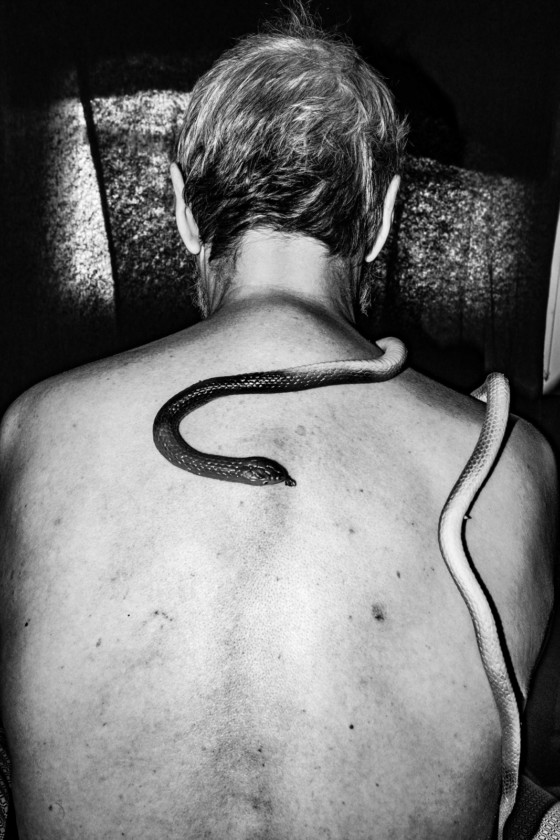

Tayla Corney – The days when the sun goes cold

Having been aware of friends and family members’ experiences with depression, Tayla Corney began his project, The days when the sun goes cold, to document experiences of mental illness which he felt were often “elusive and well-hidden”. He also wanted to experiment with photography’s potential to represent human experience. “I wasn’t too sure whether, at the end of the day, my work would have a life — but it was a process I needed to begin in order to know what photography could and couldn’t explain.” The project focuses on the physical appearance and transformation of Philippe, a man Corney met at a suicide prevention clinic in Paris. Shooting his images of Philippe in black and white, drawing on the clinicality of x-ray images, Corney nevertheless preserved a sense of intimacy in his approach, in an attempt to capture the internal trauma and isolation that arises from depression. Of his interest in black and white photography, Corney explained, “it has a harshness and softness to it. It’s balanced for me.”

Corney’s favourite aspect of his experience on the course was the human connection he took away. “Throughout the year, people got to know Philippe through the stories and pictures I shared during critiques, and to have him [attend the end-of-year exhibition] after all of it was special. He got to engage with people who had found a bond in him and the work.” Sharing meals and time together working collaboratively on the project, the two developed a friendship.

A challenge for Corney was learning to work with the inherent invisibility of the subject matter, “finding the proper visual language which would explain this illness which lies beneath the skin”. He says, “often the work didn’t transmit the trauma and severity of Philippe’s illness. The success of the work lay in finding the balance between intense images and images of everyday life. Not over-emphasizing or exaggerating everything in order to achieve a certain atmosphere. It was something as a novice artist you have to learn. Truth and simplicity are the key to a body of work.”

One particularly valuable piece of guidance came for Corney from Sohrab Hura during one critique session. Hura challenged him to think deeply about his artistic voice. Corney realised, “[The project] wasn’t going to get to where it could if I continued with it in the direction it was going. It would have just been average. And I think this penny-drop made the biggest difference.” He adds, “you have to make work which is truly yours. You cannot compromise your work based on opinions or trends. Sometimes you have to wait your turn, but when it happens for you, you will feel proud of yourself.”

Eleonora Bendi – Night Beasts

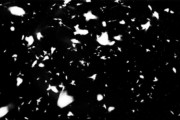

Eleonora Bendi’s project focused on industrial harbours across Europe. It saw colossal and looming coastal infrastructure transform, at night, into elements of a bestiario (bestiary) – the term for catalogues of fantasy creatures which were written and illustrated in volumes originally compiled by classical and medieval scholars. “In the post-industrial era, [the harbours] come into sight as a vestige of another time, part of a contemporary mythology that I try to put into light,” Bendi says.

She explains, on the intention behind putting the project together over a series of nocturnal shoots: “The nightfall sublimates [the architecture’s] transition from the status of object to the status of subject.” Bendi carefully considered her usage of shutter speed, aperture and tripod, in attempt to capture the buildings as posed subjects, and applied the same protocol to her image-making through each photograph in the series.

A challenge which Bendi found most interesting was securing access to the industrial sites her project focused on, often places under protection as sites of national interest. “Finding the perfect spot to shoot often requires research and sometimes sneaking in,” she says. “I love driving in the night and finding myself in inaccessible places gives a “detective” dimension to the shooting process. That amplifies the feeling of intimacy with the photographic subject.”

Bendi found that working intensely on a landscape-based photographic project can provide an immense sense of peace and fulfilment, “I enjoyed the time spent in front of these magnificent structures, absorbed in the silence and the solitude of the night.”

Asked about how the course influenced a change in her working practices, Bendi said “I gained a broader and deeper understanding about all the steps implicated in the process of creating a photographic project and I developed a passion for working with a large format camera.”

The Creative Documentary and Photojournalism course from Spéos and Magnum Photos is currently accepting applications for 2020-2021. To read more information, visit this link.