When Walls Talk

Thomas McMullan explores the significance and the symbolism of walls in the work of Magnum photographers

Walls speak, walls silence. For a photographer, walls are barriers; to people, to places, to light. But they also form backdrops. Walls are theatrical. Walls perform, often loudly, even though they are motionless, even though they divide, demark, and contain.

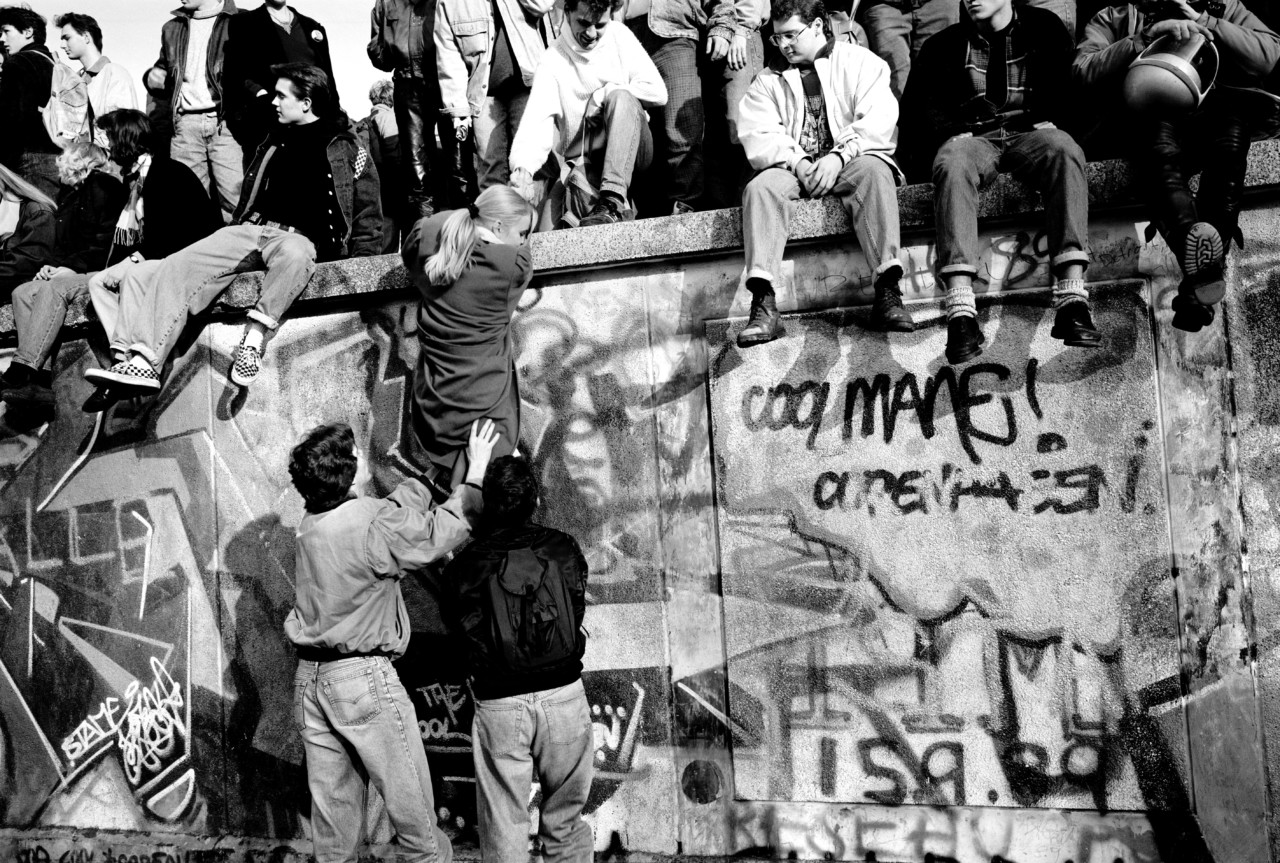

Mark Power’s photographs of the fall of the Berlin Wall are noisy with crowds, perched on concrete clamorous with graffiti. Taken on the opening between East and West Berlin on 9 November 1989, and in the days that followed, these pictures capture guards, revellers and journalists on and around the wall.

In one shot, hundreds of people sit and stand above a group of East-German guards; the wall a tide breaker against the West. In another, a man and woman climb a makeshift ladder to join a row of happy straddlers. They scale a literal wall of text.

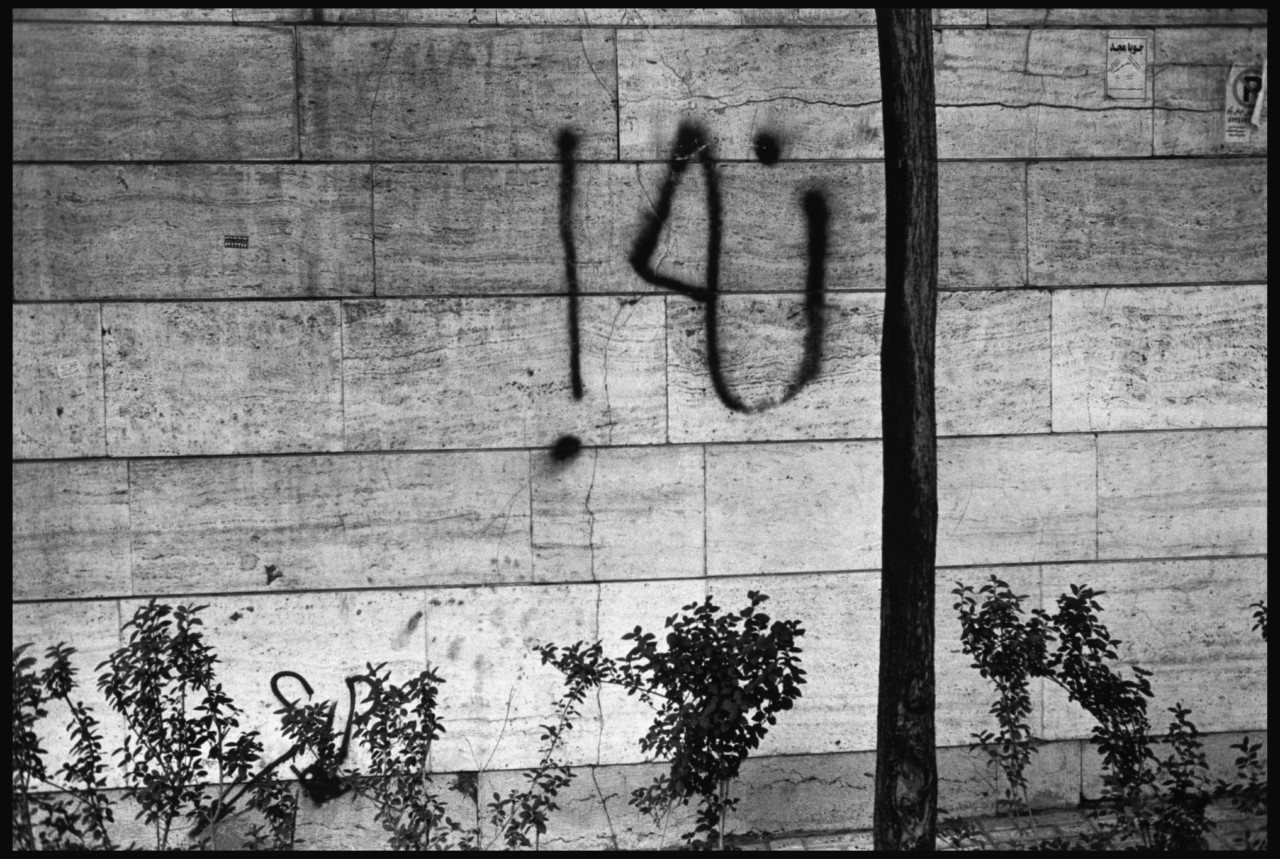

Walls might have ears, but they also have mouths. Speaking about a photograph of graffiti he took in 2001, Abbas recalled that: “During the Iranian Revolution, the walls of Tehran spoke”. On the walls of the city, he said, you would find poems jostling beside slogans, besides rallying shouts. “Years later, this simple cry, NA (NO in Farsi) appeared on a wall in Tehran… History has come full circle. The walls are speaking again.”

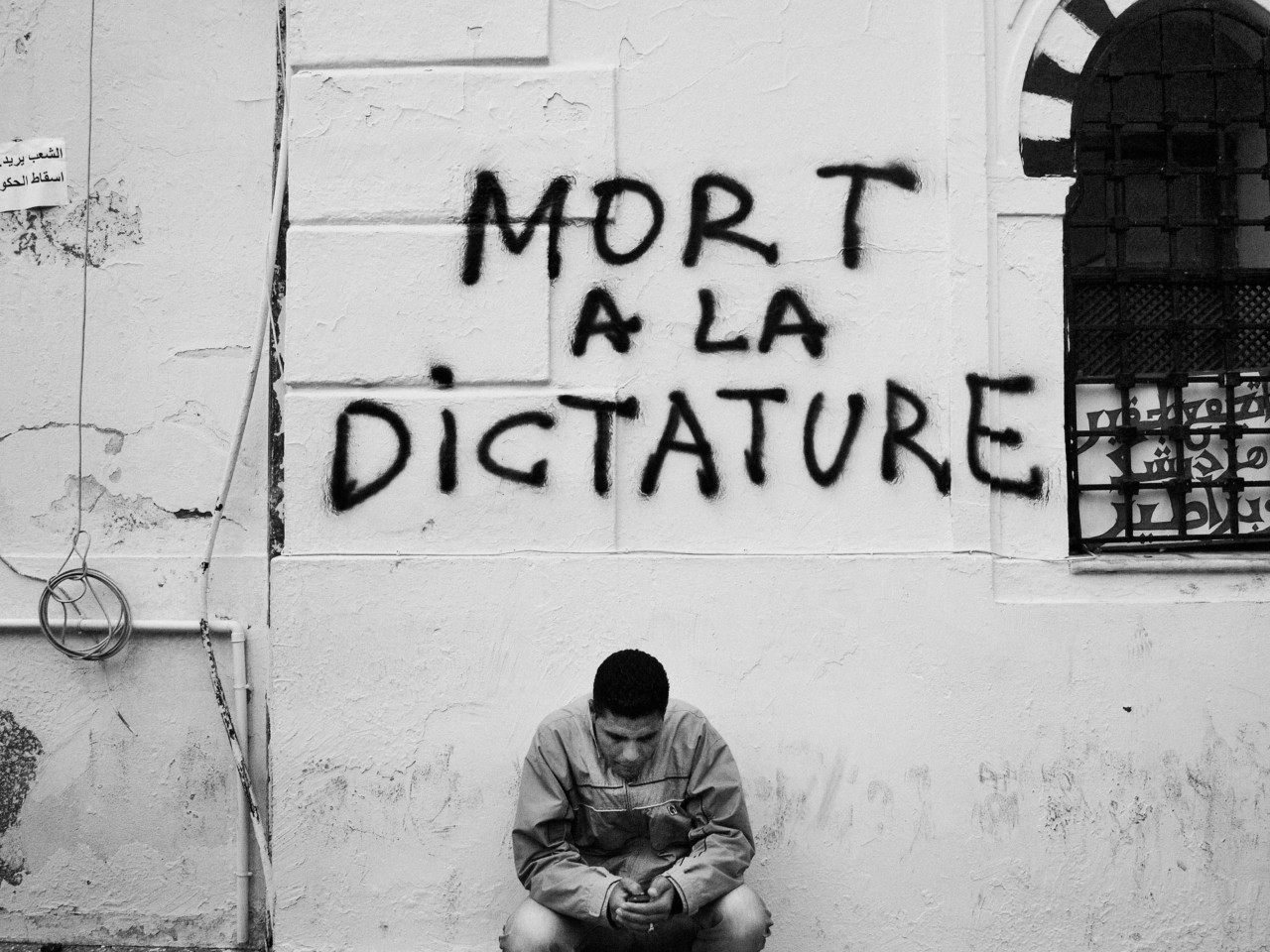

Abbas’ speaking wall finds a brother in a 2011 shot by Alex Majoli, taken during riots in Tunisia. A man squats against a wall staring at his mobile phone. Above him the words MORT A LA DICTATURE (death to the dictatorship) loom like a comic-strip speech bubble. The framing of the person and the wall creates a kind of expressive scenography. Is it the wall who speaks here, or is it the man?

A similar relationship was created in Majoli’s first book, Leros, which documents the occupants of a psychiatric hospital on the titular Greek island. Throughout the collection, the peeling walls of the institution, formally a political prison, are a near-constant presence; broad and bare against the bodies of the inmates.

In a number of shots, however, these walls become canvases. In one picture an elderly patient is sat against a white expanse, punctured by a pair of flowers. In another, a juddering man wearing trousers too big for his legs stands in a rubble-strewn corridor, a drawing of Jesus floating above his head. These walls speak for the inmates, they become expressions of the minds constrained by them; the internal perceptions made external.

“Leros is a little chapter from a long story of Franco Basaglia’s work,” says Majoli, referencing the Italian psychiatrist who was fundamental in abolishing mental hospitals in Italy. “It’s all about breaking the walls of perception.”

The subjects of Bruce Davidson’s Subway are also shot against walls of graffiti. Writing about the collection, he says: “I wanted to transform the subway from its dark, degrading, and impersonal reality into images that open up our experience again to the colour, sensuality, and vitality of the individual souls that ride it each day.” The walls of the New York subway carriages are a key part of this. At turns claustrophobic and intimate, the tight spaces of the underground squeeze their occupants, but the graffiti, signs and adverts cast these faces in a cacophony of expression. WELL DAMN, one wall blurts behind an elderly woman wielding an accordion. In another shot, a right-angle of near-incomprehensible lettering spreads above a woman with a gold earring. The subway becomes a stage.

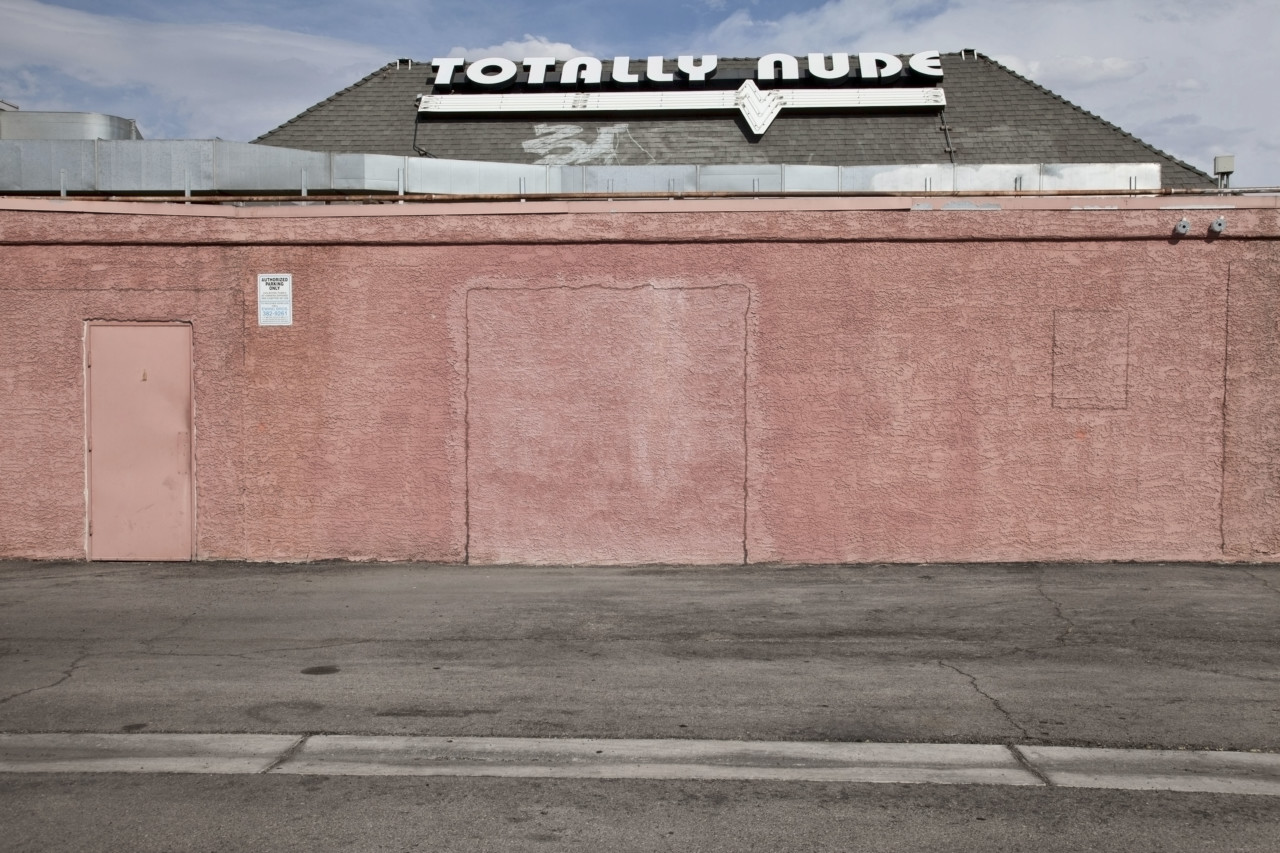

In Susan Meiselas’ shots of the American West in 2011, the stage is built from strip clubs and shop windows. A pink wall encircles a building that claims to be TOTALLY NUDE, the ghosts of bricked up entryways are clear to see. Elsewhere, paint peels from a facade of a naked woman on a cliff edge (which also seems to be a woman’s head). Elsewhere still, a billboard on a truck for a topless bar renders its model monolithic against a man in a checked shirt, who is positioning a cardboard cutout of another man. These walls are beguiling; as a fantastic as film sets.

Josef Koudelka started his career with commissions from theatre magazines. It’s an influence that ripples beneath his work. Writing in the exhibition publication for Exiles, Anna Fárová says: “Here, for the first time, Koudelka has placed alongside his humanistic photographs shots of the vacated backstage of the city, the theatre of tragic abandon.”

There are many walls in Exiles, many unyielding backdrops for people, animals and shadows. One photo, taken in Ireland in 1976, has four men with their backs to the camera, stood apart against a strange warren of concrete. It could be a Magritte painting until you realise the men are pissing. In another picture, taken in London in 1977, a man with hands in the pockets of his jacket stalks an underpass. The wall behind him climaxes: SEX SEX SEX SEX SEX SEX SEX SEX.

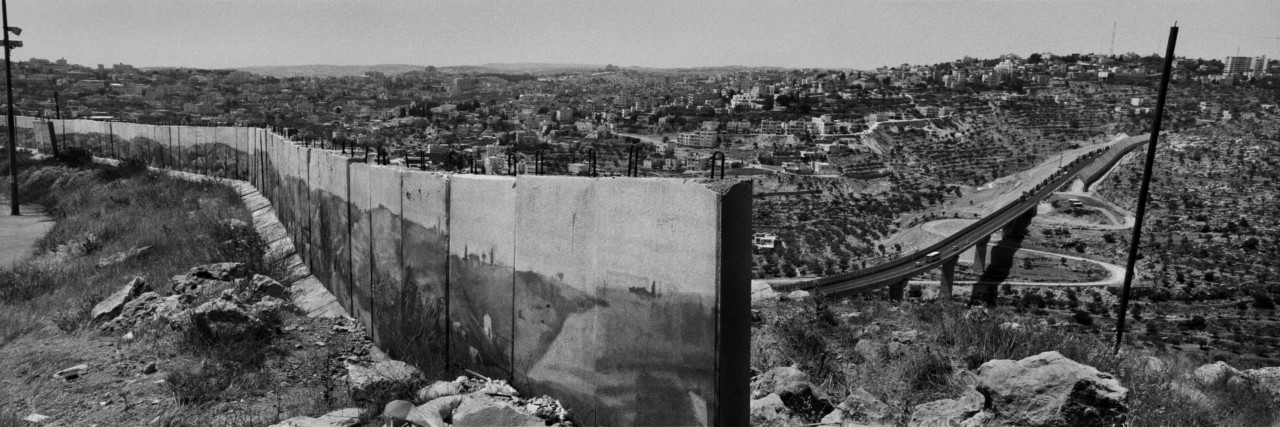

Walls babble, but they also muffle. They control. For a photographer known to wander; who for a long time was stateless and “learned to sleep anywhere and under any circumstances”, the boundary of a wall holds a particular reverberation. Koudelka’s 2013 collection Wall brings together panoramic shots he made from 2008 to 2012, centred on the West Bank barrier separating Israel and Palestine. Instead of a theatrical backdrop, the wall in these photos is the subject, snaking across East Jerusalem, Hebron, Ramallah, Bethlehem and various Israeli settlements, splitting the landscape, preventing free movement.

The use of a panoramic camera allows Koudelka to create photographs that mimic the monumental quality of the barrier. “The panoramic format corresponds with the human field of vision and it underlines the horizontal forms in the landscape,” writes Frits Gierstberg in the newsprint publication for Koudelka’s EXILES and WALL. “Indeed, Koudelka sees his pictures of the wall as, first and foremost, landscape photographs showing the devastation inflicted on what is for many people a ‘holy’ land.”

There are hardly any human figures in Wall, but there is graffiti and murals; scenography sans actors. In one photograph, a partly dismantled section of wall in Giro settlement is painted with a bucolic landscape that masks the reality of the neighbouring town. In another, the concrete slabs of the wall on the Israeli side of East Jerusalem are covered with “aesthetic panels”, creating the illusion of building facades and, most hauntingly, of entrances and windows. In reality, these shadowy passage are nothing more than black paint.

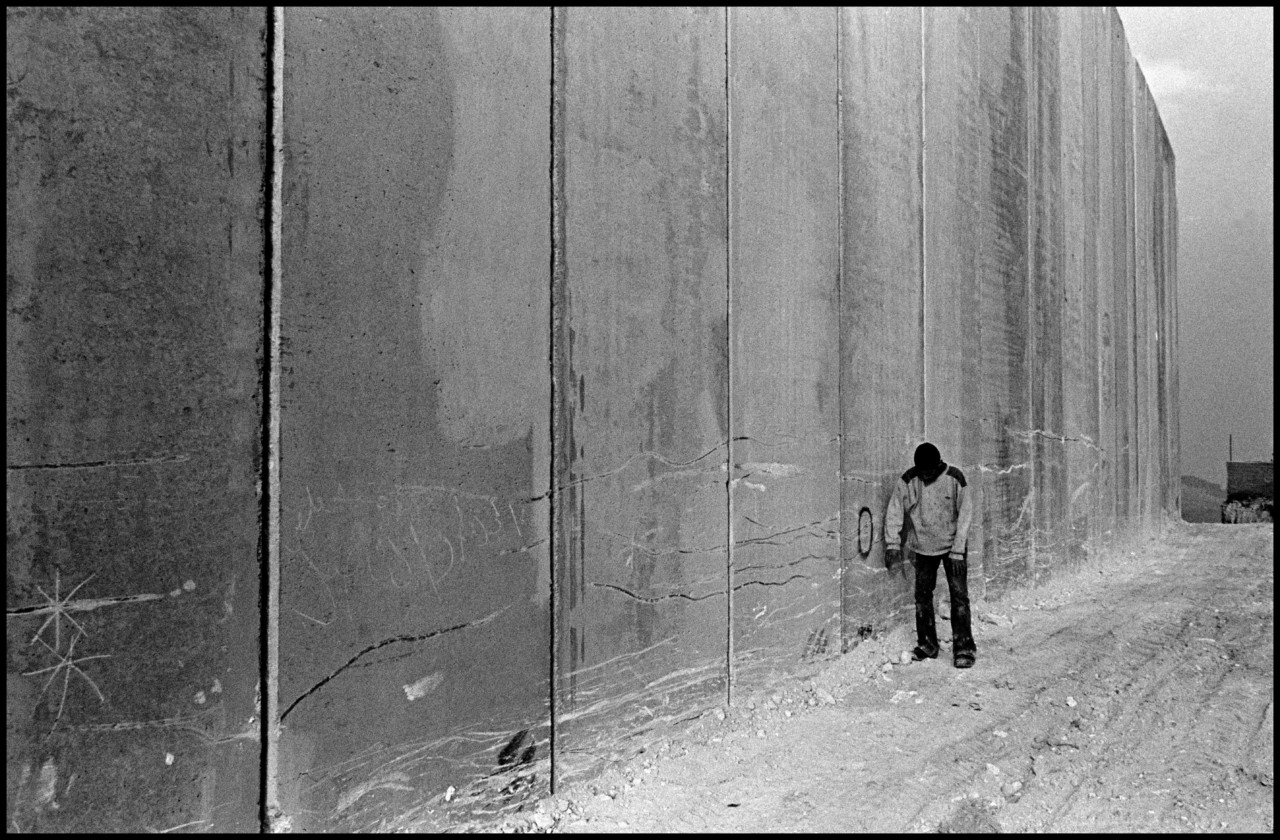

In No Man’s Land, Larry Towell pictures the physical and psychological walls of Palestine. The battered landscape is full of barriers, for control, for enclosure, for cover. There are the walls of old cities, the boundaries of Israeli checkpoints and the broken walls of Palestinian refugee camps.

“Walls have dual meanings,” he says. “They either keep you in or they keep you out. They either protect you or they deny you protection. They either take your land away or they affirm your possession. They either wall you in or they wall you out. Their purpose depends on who built the wall.”

The West Bank barrier looms large in several of Towell’s photographs. In one image a Palestinian worker stands beside a newly constructed section of the wall, staring at a circle painted on its surface. The circle is the shape and size of a man’s head, level with the worker’s stomach. Is it a piece of graffiti? Is it an imaginary porthole to the other side?

In another photo, shot in panoramic, a man is actually about to make it through. The final concrete slab is yet to be set in place, and its gap casts a strip of light across the ground, over the boulder the man is about to leap from.

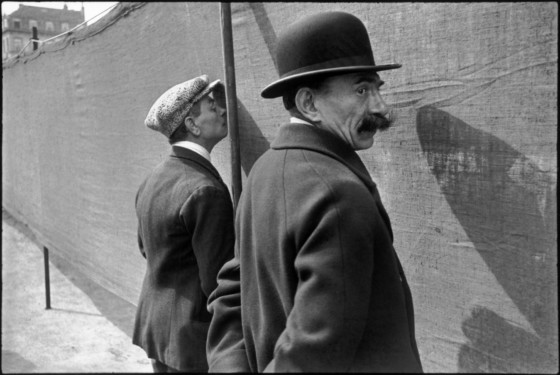

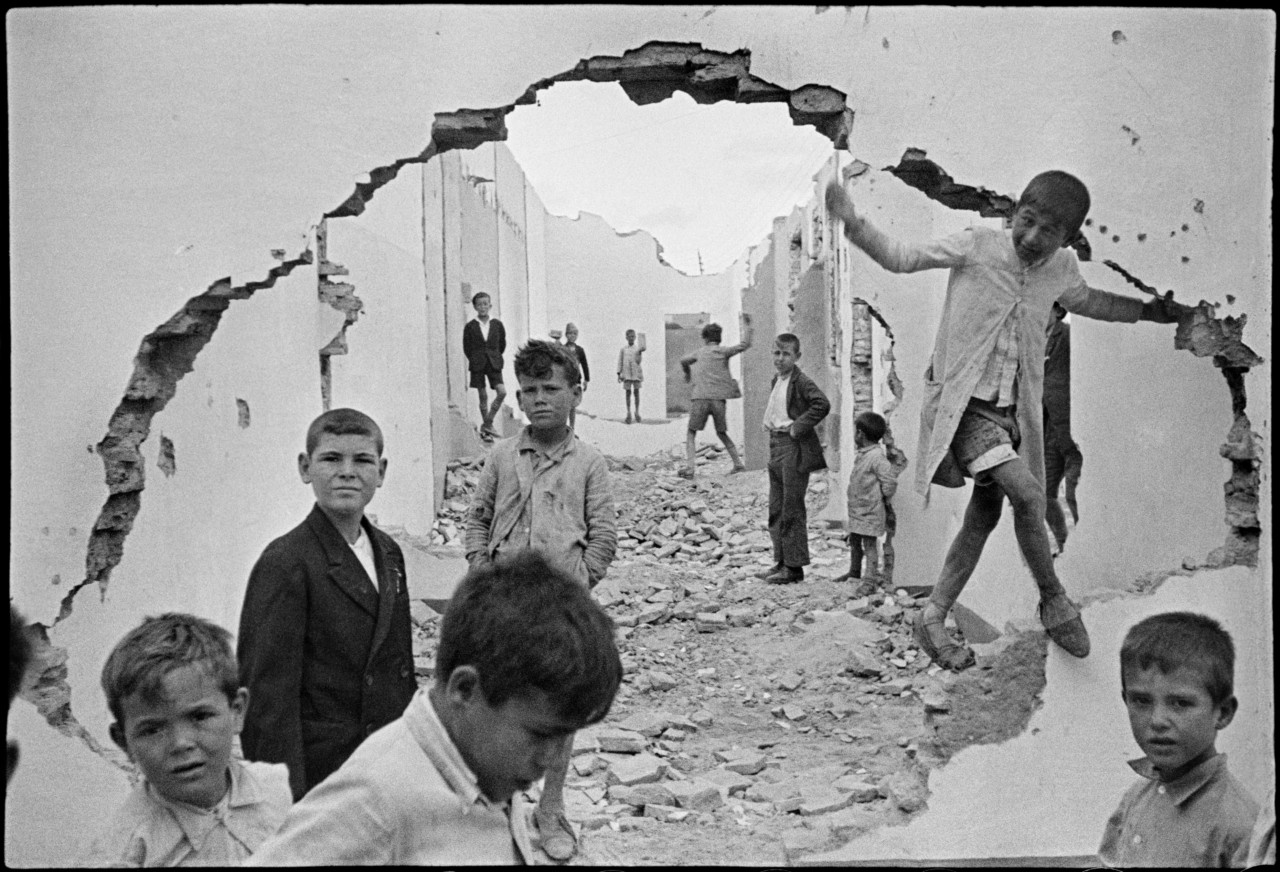

What lies behind the wall? For an artform centred on fields of vision, occlusion can be a powerful photographic technique. Henri Cartier-Bresson knew this, with his pictures that hint at spaces tucked behind city walls.

In his 1932 photograph of two men peeping through a fabric wall in Brussels, for example, the viewer is left to wonder exactly what they are so surreptitiously spying on. Similarly in his 1962 picture of three men stood atop a plinth and staring across the Berlin Wall, the source of their interest is hidden from view. What is happening on the other side of the wall?

Perhaps it is children playing, as in his iconic picture of Seville, where a hole in a wall frames youth amongst the ruins. Here the viewer is privy to what would otherwise be hidden, the riotous children seeming to burst from the photograph itself.

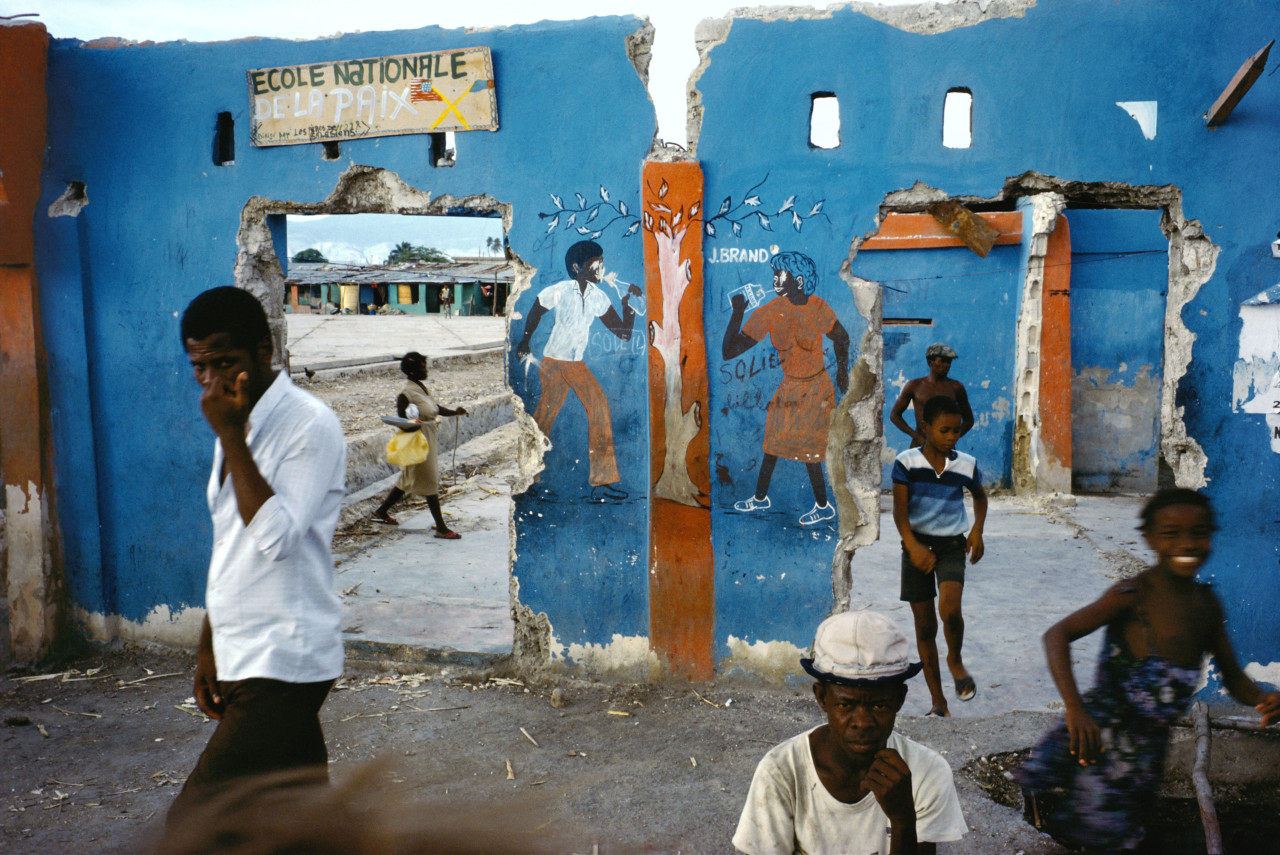

Alex Webb’s shots of Haiti in 1986 and 1987, in the wake of the departure of the country’s dictator, Jean-Claude Duvalier, hold a similar riotous energy. Hope for democratic reforms faced a wave of violent unrest, and Webb captured this period against the vivid colour of crumbling walls. In one particular picture, people surround a mural of a man and a woman beneath a tree. The former Ecole Nationale de la Paix has been blown apart, but this striking blue wall remains. What lies beyond is, if only for a moment, confused by the bodies glimpsed through the doorways and those painted in the mural; as if they have bled into each other.

In another picture, a woman in a pink dress moves in front of a wrecked warehouse. There is no hopeful painting here, only destroyed windows framing dark clouds. The blurred body seems as transient as the pockmarked wall, as if a strong gust of wind will blow both of them away.

In Cartier-Bresson’s 1933 shot of a child stood in front of a damaged wall in Valencia, the surface has not shattered, but it seems as if it might. The paint has peeled, leaving a star-strewn void across the side of a building. The child has one hand to this wall, ecstatic. The wall is at all once a backdrop, a canvas, a division. It is monumental at the same time it is intimate.

If walls do speak, this one has a particularly sonorous voice.

Thomas McMullan is a writer and journalist. His first novel, The Last Good Man, will be published by Bloomsbury in 2020.