The Language of Dance

Henri Cartier-Bresson photographed workers and aristocracy alike, animated in movement

Dancing is intimate — the body’s movement to the music, the physical and emotional connection between two people— dance can enable usually introverted individuals to convey the smallest emotion and express themselves unlike anything else. Emotion and movement are both evident in the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Famed for his street photography, especially of children, in naturalistic states, his work communicated a sense of kinetic energy and flow, just like a dance in motion. His subjects seemingly never stopping their activities, not even for him. His photographs of ballroom dancing are a fascinating example.

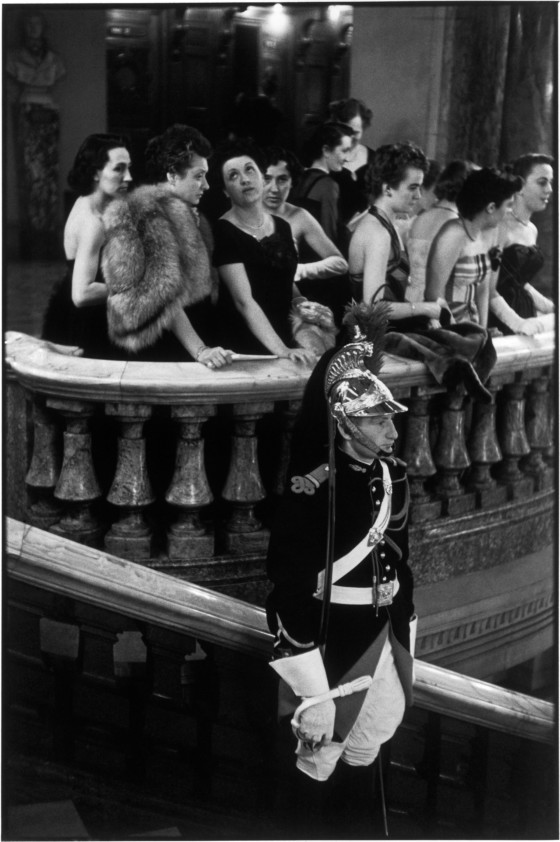

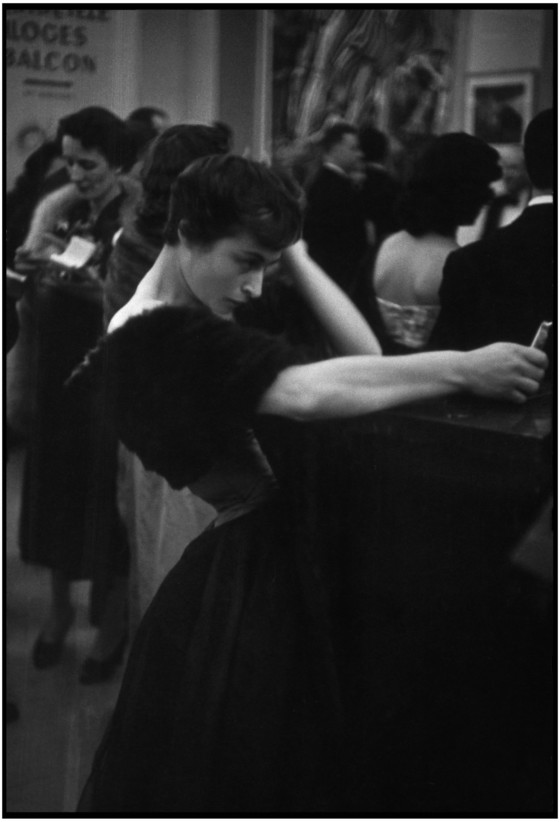

Like the surrealists whose circle he moved in, Cartier-Bresson had an eye for the unusual and the uncanny, injecting the marvellous into the smallest of details. In the words of art historian Peter Galassi, the surrealists “saw that ordinary photographs, especially when uprooted from their practical functions, contain a wealth of unintended, unpredictable meanings.” Whether capturing attendees at Parisian society balls, royal functions in London, debutantes in New York or workers in the Soviet Union dancing in their canteen, Cartier-Bresson always applied the same keen eye and intimate detail. Every image, each moment of dance, presents an emotional connection between people.

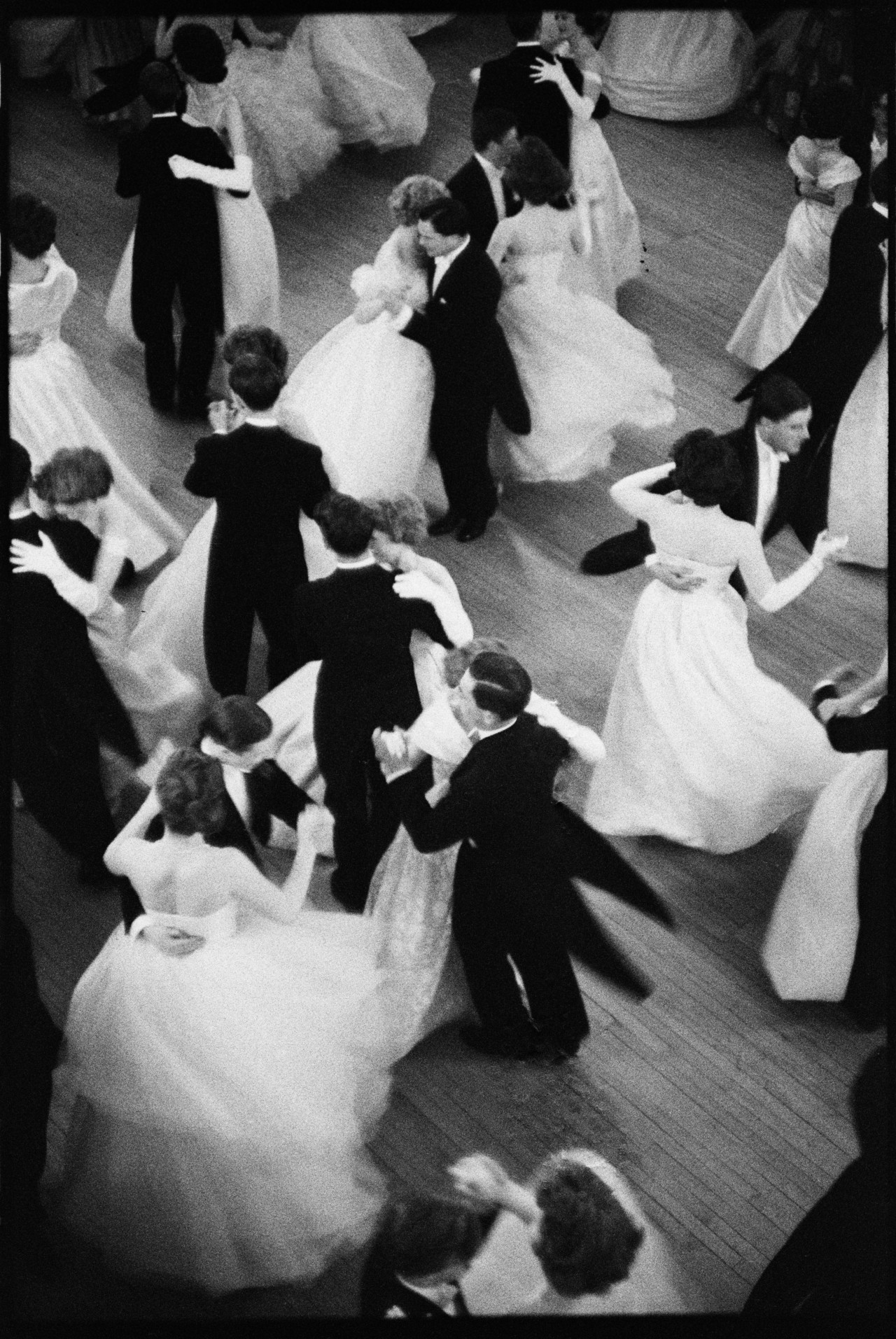

In the image of Queen Charlotte’s Ball from 1959, the camera captures a scene from above the dancefloor. An annual debutante ball that took place in London from 1780 to 1976, and was resurrected in the early 2000s, the function served to ‘promote’ young women of prominent social ranking and to celebrate their places as newly-recognized adults in high society. Cartier-Bresson’s scene attracts our gaze to the voluminous taffeta of the young women’s dresses moving as they spin in time to the music, their partners’ suit tails mimicking their motion. The scene is alive, filled with possibility for the women in the scene for whom the dance is a social ritual signalling their next steps into a new life stage.

"Every image, each moment of dance, presents an emotional connection between people."

-

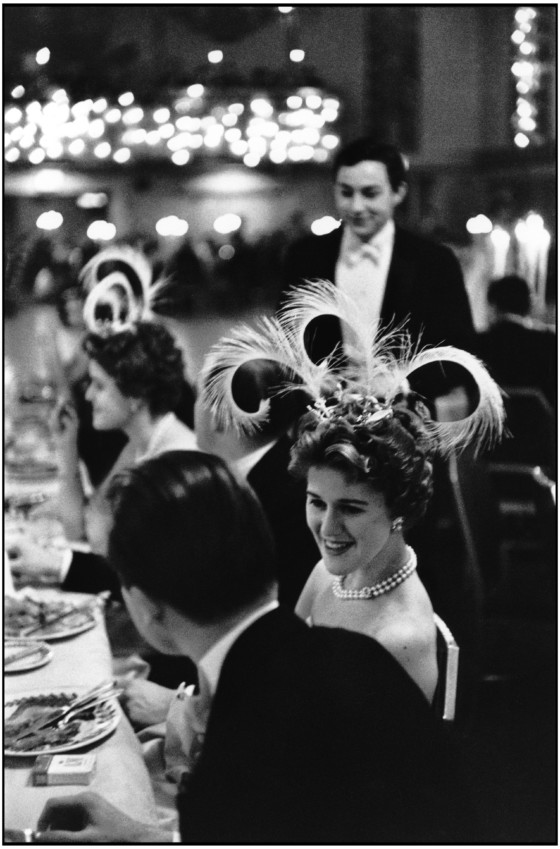

In another image, we see a dinner scene inside the Palais de Chaillot, where the annual Bal des Petits Lits Blancs is taking place. A guest appears to be serving herself and her companion, a dutiful waiter holding the tray of meat and vegetables over her shoulder. Although we don’t see dancing, Cartier-Bresson has captured the life and movement in the scene: the waiters serving their guests as they move from table to kitchen, and the guest directing his companion about which particular morsels he desires from the glistening silver platter. It is a moment of action, of emerging personalities, bustle and movement in the background. It is not a dance in the traditional sense, but of the servers navigating tables, dancing across the frame. Cartier-Bresson has demonstrated how dancing is not always confined to the dancefloor.

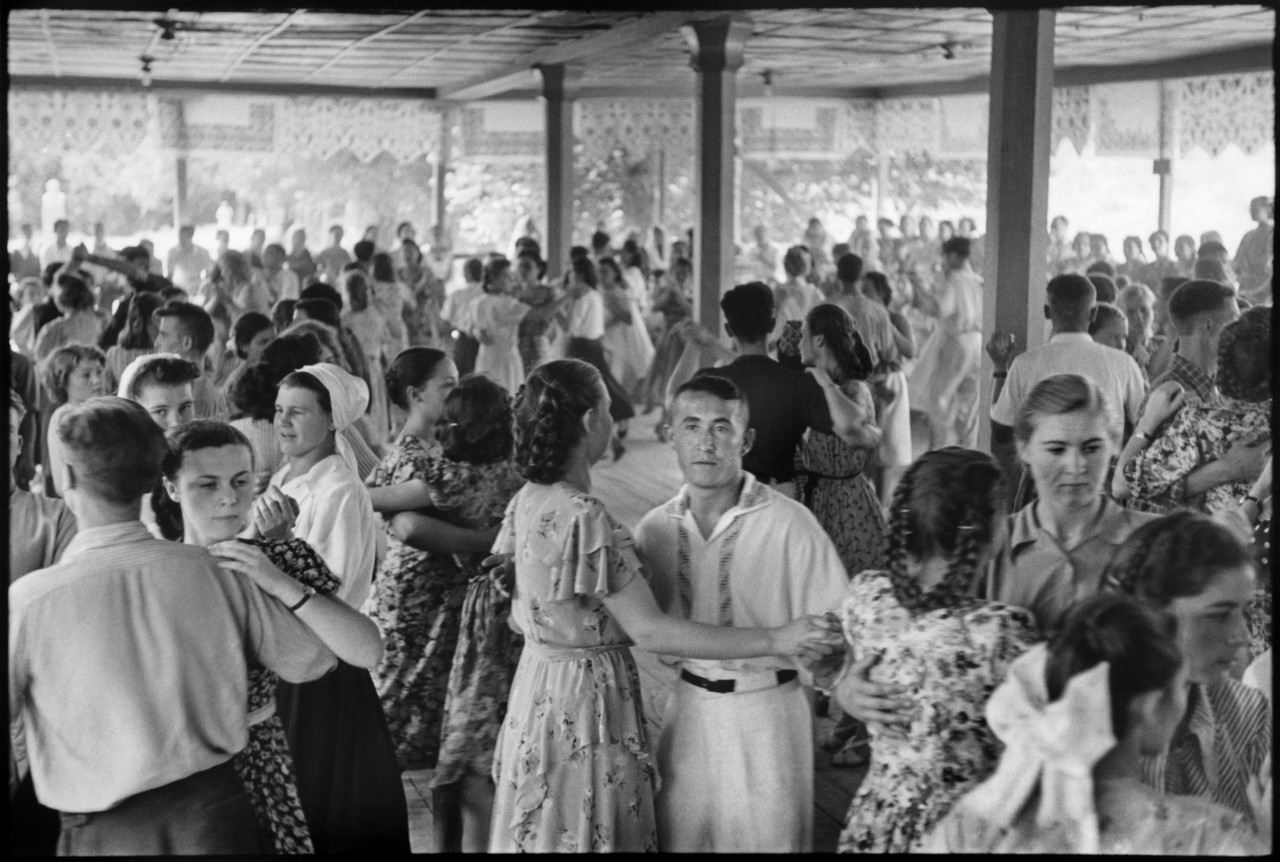

Although this is a busy moment, there are also the quieter moments of introspection. A young couple at a debutante ball in New York dance their bodies tight together, their movements small, the understated smile across the young debutante’s face, as though we are witnessing a private moment of introspection. Another young woman is present, slightly blurred in the background, her facial expression more open and exuberant. It’s a beautiful moment highlighting the connection between the couple.

"...we are peeking into something secret, we are unseen observers, yet once again it does not feel like an invasion. "

-

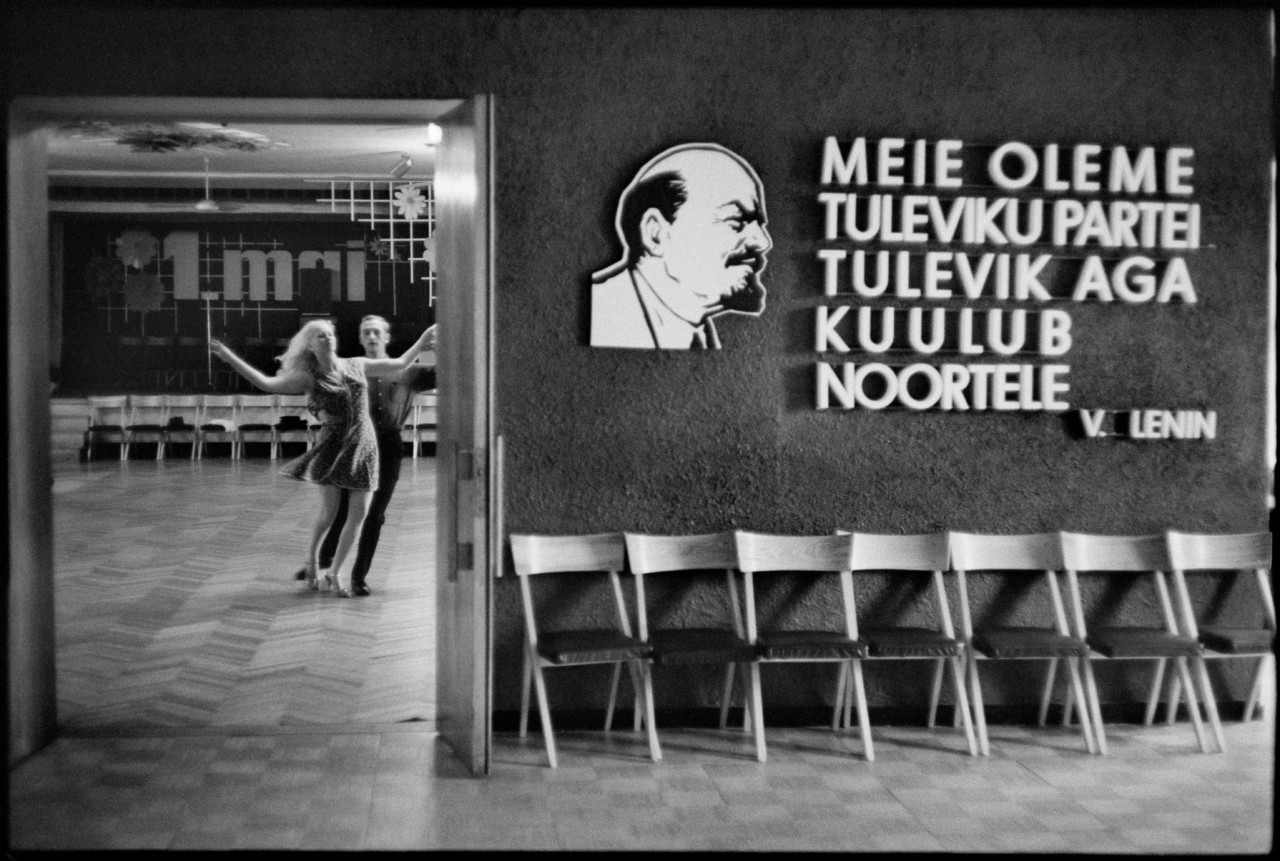

Cartier-Bresson was an artist of people, and whether he was recording the wealthy and aristocratic in European palaces or workers in the Soviet Union rehearsing for a dance competition, his keen eye and finesse of detail treated every subject equally. His photograph of workers in Estonia rehearsing for their dance championship demonstrates what continues to make his art so special: individuals expressing themselves seemingly without any interruption. The framing of the photo – we see them through the door – makes it appear that we are peeking into something secret, we are unseen observers, yet once again it does not feel like an invasion. The woman, immersed in the dance, has raised her arms and her partner guides her around the floor. Outside the room foldable steel chairs are lined up and a quote by Lenin in large lettering — “meie oleme tuleviku partei tulevik aga kuulub noortele” — can be seen on the wall. “We are the future of the party,” it says, “however, the future belongs to the young.” The serves to emphasise how dance can function on a political and social level: these workers are a far cry from the palace and the high class ballrooms. Where once ballroom was the dance for the gentry and folk for the workers, boundaries can be broken; dancing can transcend these social stigmas.