Beyond The Dream: The Radical Politics of Martin Luther King Jr., 50 Years On

Fifty years after his assassination, Harvard scholar Brandon M. Terry makes the case for the intellectual and political significance of Martin Luther King Jr. and his radical ideas

Magnum Photographers

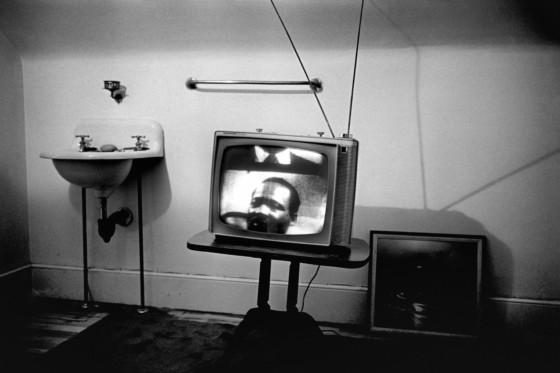

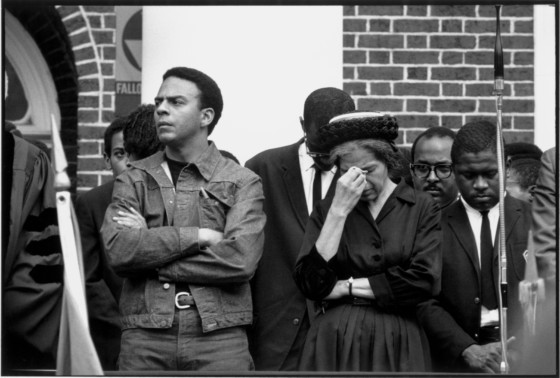

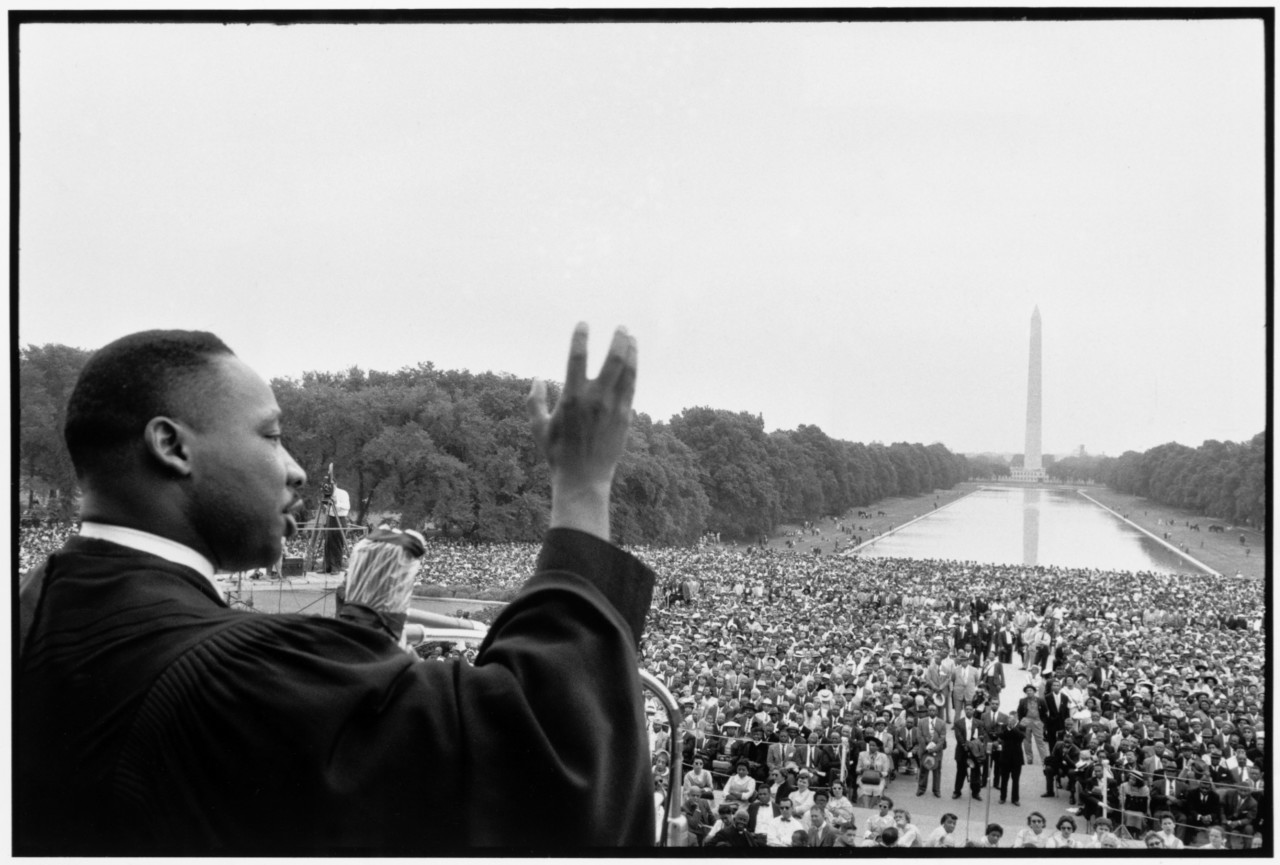

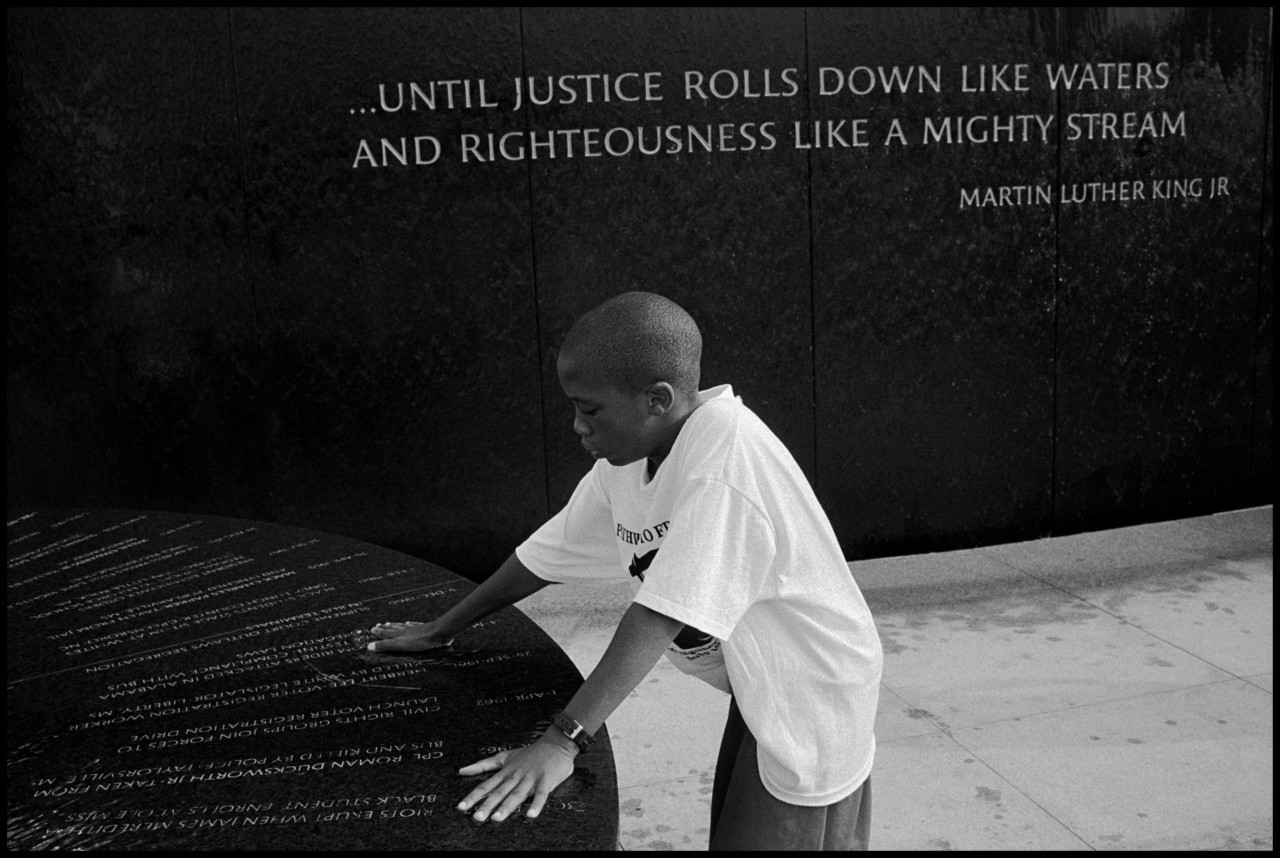

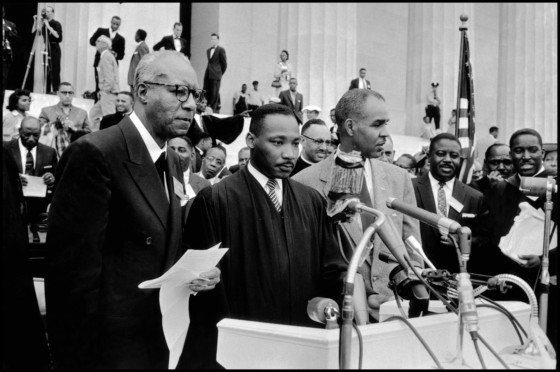

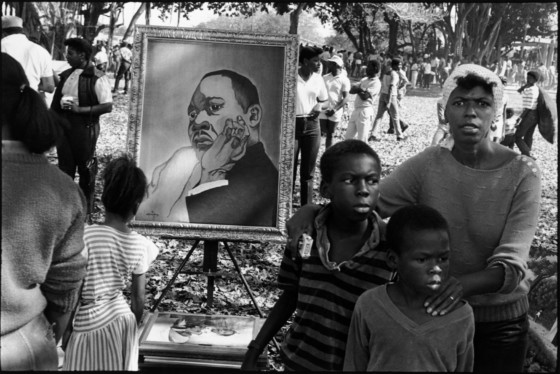

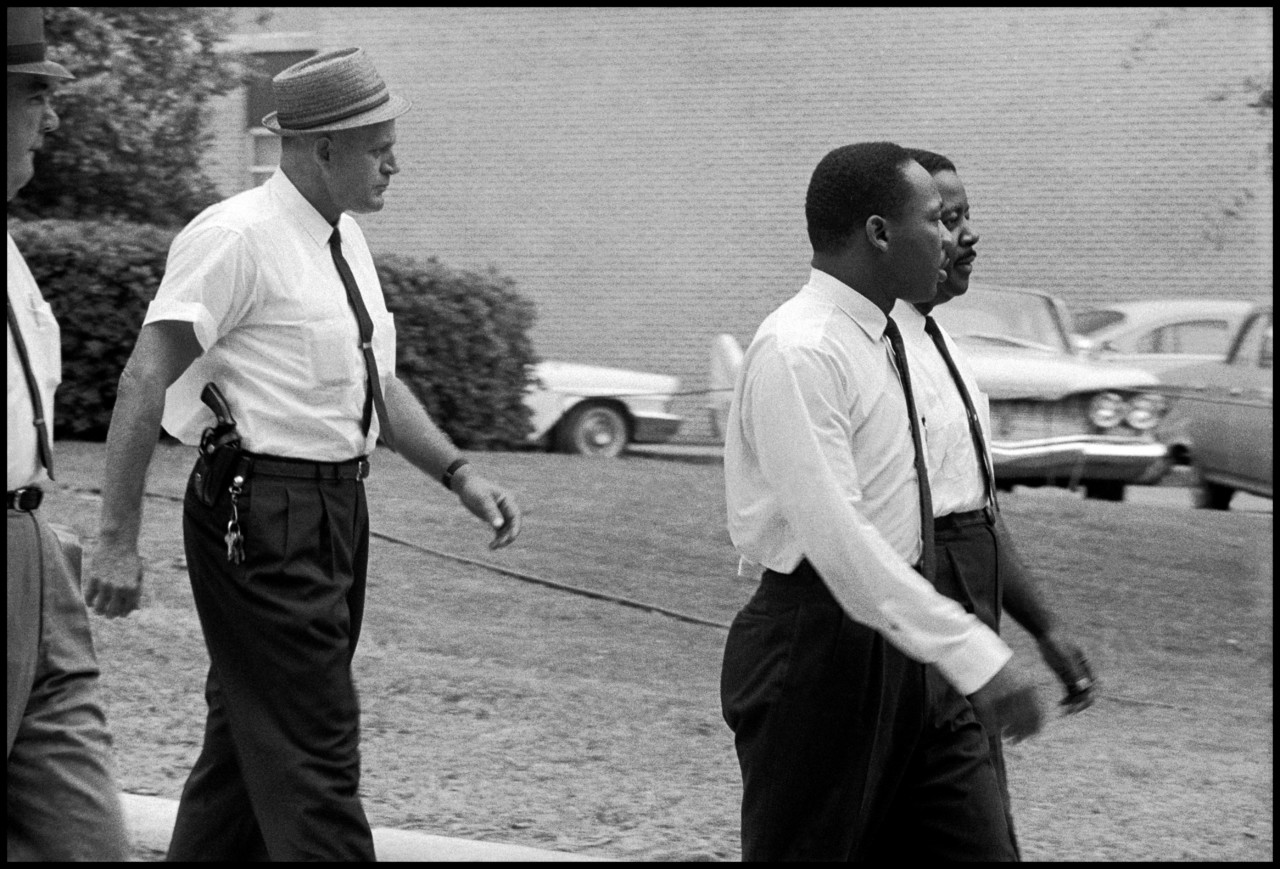

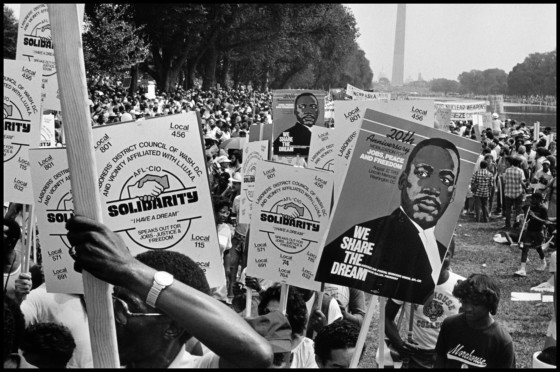

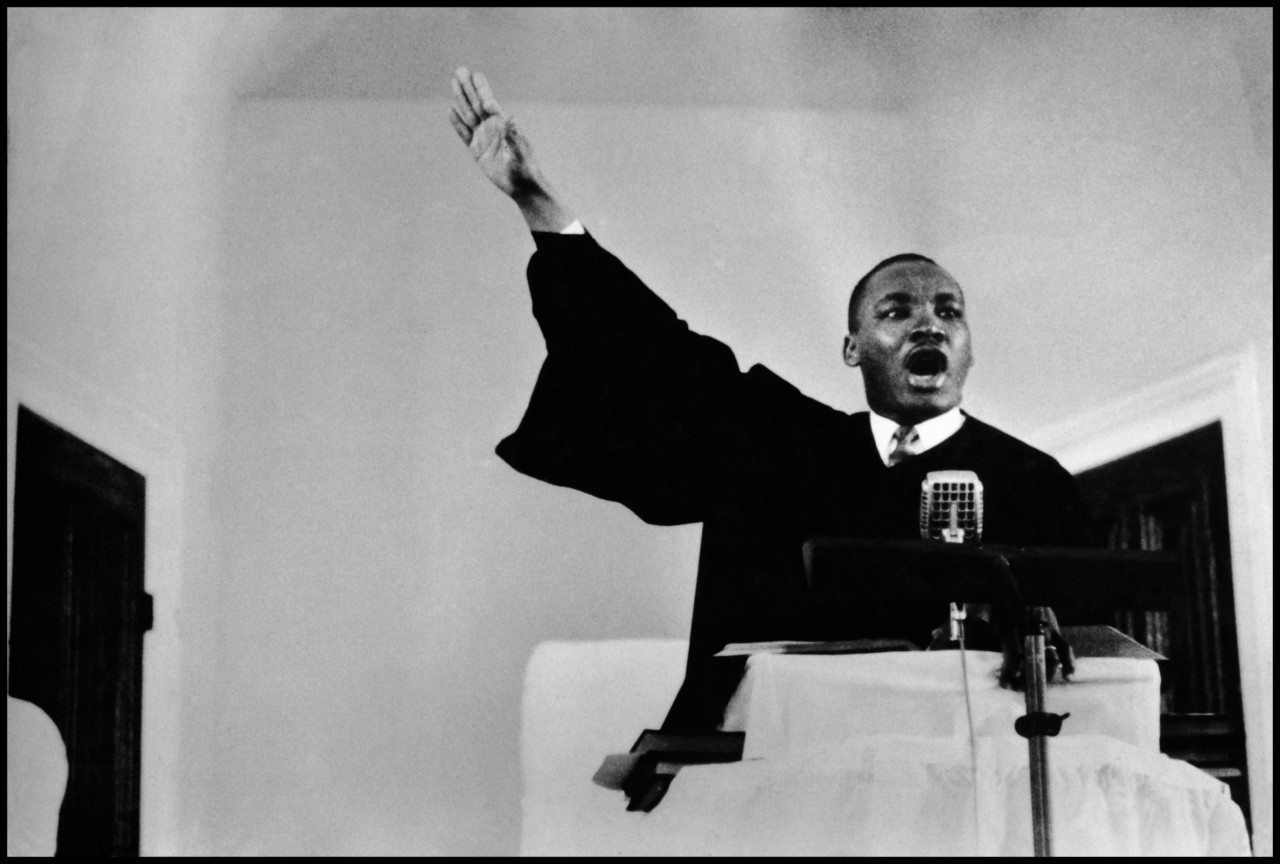

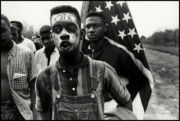

On April 4, 1968 Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot while he stood on the balcony of a Memphis motel. Magnum photographers had spent years documenting King and the pivotal role he played in the civil rights movement in the United States — and in the aftermath of his death, they continued to do so, capturing the country’s response and his legacy as an icon.

Brandon M. Terry is an assistant professor of African American Studies and Social Studies at Harvard University. This is an edited excerpt of an essay published in Boston Review’s print issue, Fifty Years Since MLK, exploring how Martin Luther King’s influence on generations of activism and contribution to political thought today.

On February 23, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr., took to the stage at a sold-out Carnegie Hall. He had not come to rally the flagging spirits of bloodied civil rights demonstrators, shake loose the pennies of liberal philanthropists, or even to testify to God’s grace. A more solemn task was at hand.

King was the keynote speaker for a centennial celebration of W. E. B. Du Bois’s birth. Arguably the greatest political thinker and propagandist black America ever produced, Du Bois spent his last days in relative ignominy in Ghana, his passport canceled by the U.S. State Department in retaliation for anti-nuclear, anti-racist, and socialist politics. Du Bois died on the eve of the 1963 March on Washington, denied the chance to witness the moral authority of the civil rights movement crystallize before the world.

Stating that Du Bois was “a genius and chose to be a Communist,” King insinuated that Americans’ reflexive aversion to political radicalism remained an obstacle to critical thinking and good judgment. Spoken barely forty days before King was shot dead on a Memphis motel balcony, the remarks honored Du Bois’s trailblazing politics and, in hindsight, suggest worries King may have been harboring about his own legacy.

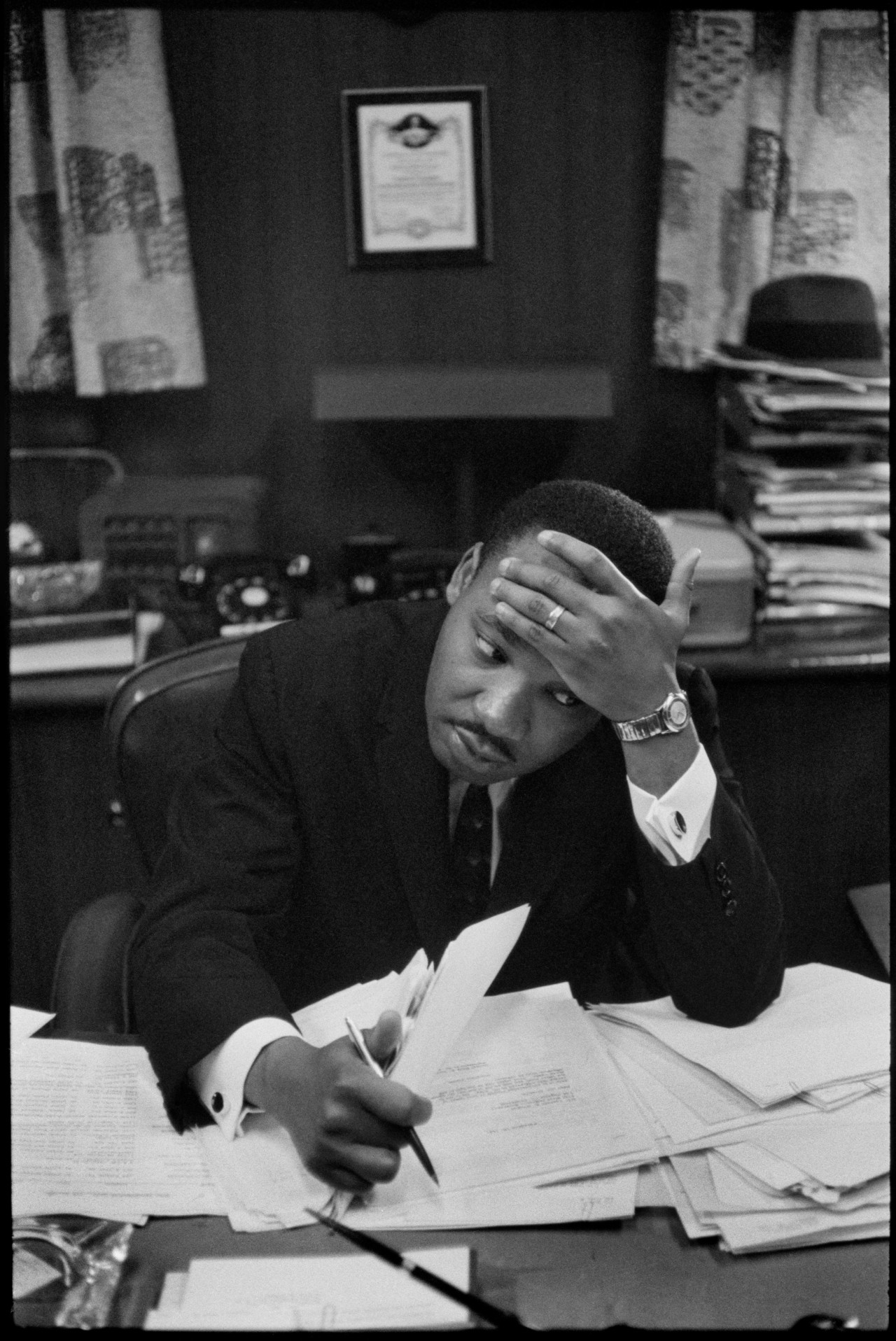

Those worries are easy to understand. In the year before King’s death, he faced intense isolation owing to his strident criticisms of the Vietnam War and the Democratic Party, his heated debates with black nationalists, and his headlong quest to mobilize the nation’s poor against economic injustice. Abandoned by allies, fearing his death was near, King could only lament that his critics “have never really known me, my commitment, or my calling.”

Fifty years after his death, we are perhaps subject to the same indictment. As we grasp for a proper accounting of King’s intellectual, ethical, and political bequest, commemoration may present a greater obstacle to an honest reckoning with his legacy than disfavor did in the case of Du Bois. There are costs to canonization.

The King now enshrined in popular sensibilities is not the King who spoke so powerfully and admiringly at Carnegie Hall about Du Bois. Instead, he is a mythic figure of consensus and conciliation, who sacrificed his life to defeat Jim Crow and place the United States on a path toward a “more perfect union.” In this familiar view, King and the civil rights movement are rendered—as Cass Sunstein approvingly put it—“backward looking and even conservative.” King deployed his rhetorical genius in the service of our country’s deepest ideals—the ostensible consensus at the heart of our civic culture—and dramatized how Jim Crow racism violated these commitments.

Heroically, through both word and deed, he called us to be true to who we already are: “to live out the true meaning” of our founding creed. No surprise, then, that King is often draped in Christian symbolism redolent of these themes. He is a revered prophet of U.S. progress and redemption, Moses leading the Israelites to the Promised Land, or a Christ who sacrificed his life to redeem our nation from its original sin.

"Our saturation with images of suffering (black and otherwise) and the balkanization of the media have altered how we respond to documentary images, raising doubts about whether we remain as receptive to King’s strategies of public spectacle."

- Brandon M. Terry

Such poetic renderings lead our political and moral judgment astray. Along with the conservative gaslighting that claims King’s authority for “colorblind” jurisprudence, they obscure King’s persistent attempt to jar the United States out of its complacency and corruption. They ignore his indictment of the United States as the “greatest purveyor of violence in the world,” his critique of a Constitution unjustly inattentive to economic rights and racial redress, and his condemnation of municipal boundaries that foster unfairness in housing and schooling. It is no wonder then that King’s work is rarely on the reading lists of young activists. He has become an icon to quote, not a thinker and public philosopher to engage.

This is a tragedy, for King was a vital political thinker. Unadulterated, his ideas upset convention and pose radical challenges—perhaps especially today, amidst a gathering storm of authoritarianism, racial chauvinism, and nihilism that threatens the future of democracy and the ideal of equality.

In the decades following his death, cynical appropriations of King have become such a reliable feature of public discourse that many younger Americans greet his name with suspicion. Indeed, even those in the Movement for Black Lives, despite commitments to nonviolent direct action and democratic politics, have often sought ostensibly more “radical” ancestors to claim, such as Malcolm X, Assata Shakur, Fred Hampton, and Audre Lorde.

Perhaps this is penance that had to be paid. King’s blindness to the gendered dimensions of charismatic authority and hierarchical leadership within protest organizations—and the black church—is surely reason enough to be critical of his example.

Moreover, the black church—which in the nineteenth century Martin Delany called the “Alpha and Omega” in black communities—is today a profoundly weakened institution. The church faces many challenges in our era of political and social integration, prosperity theology, political party clientelism, social conservatism, and heavily publicized sexual and financial corruption. King’s theological commitments were once part of his allure. Now they present an impediment to his embrace among the “unchurched.”

Some of the present eschewal of King, however, seems less fair and more superficial. In a world irrevocably transformed by the sexual revolution and secularism—not to mention urbanity, black street culture, and the ascendancy of ironic art and self-expression—King can appear both terribly staid and uncomfortably earnest. Burdened with utterly unique political responsibility and his own impossible standards of ethical excellence, King’s words and persona seem weighed down, even beyond the grave, with a self-restraint that can make him feel older, less “cool,” and more distant than black male contemporaries such as Malcolm X or Baldwin.

"In a world irrevocably transformed by the sexual revolution and secularism. King can appear both terribly staid and uncomfortably earnest."

- Brandon M. Terry

Engaging King’s ideas about racism, political action, and ethics is, of course, not the same as agreeing with him, much less treating him as the object of uncritical adulation. It is simply to treat him as a profound interlocutor and model of political judgment. King teaches us that the morphology of protest should be treated as a perpetual question, one experimentally and imaginatively rethought in light of technological, cultural, political changes.

This learning will not be easy. Our saturation with images of suffering (black and otherwise) and the balkanization of the media have altered how we respond to documentary images, raising doubts about whether we remain as receptive to King’s strategies of public spectacle. Racial stereotypes have also transformed. Few would now identify blacks with passivity; on the contrary, black protesters are regularly labeled as aggressive, ungrateful, and dangerous. Social media has created a low-cost outlet for every utterance of resentment to gain a hearing. The practice of public assembly has been forever altered by the possibility of terrorism.

And nonviolent resistance has become ritualized, with police trained in forms of protest management that rob civil disobedience of the drama of punishment and sacrifice that once gave it gravitas. Street marches, as King predicted, now need to reach massive levels of participation and organization if they are not to be “mere transitory drama” absorbed by “the normal turbulence of city life.”

Even the geopolitics of protest has changed. Authoritarian rulers are ascendant at home and abroad, European liberals are in retreat, and Donald Trump (as Barack Obama did before him) issues unilateral, global assassination orders from an office decorated with King’s bust. The idea that Americans will be ashamed in the eyes of the world, central to King’s Cold War–era politics, now seems quaint. In recognition of this shift, the longstanding interest among black activists in symbolic appeals to the United Nations and human rights forums has been eclipsed by a mix of domestic protest and electoral politics.

Still King’s call to internationalize nonviolent social justice movements continues to matter in at least one important respect. We face global existential challenges of climate change, nuclear weaponry, war and terrorism, and wealth inequality (abetted by offshore tax havens and attacks on capital controls).

But as we scour for exemplars of struggle, we must not write off the United States’ most peculiar radical and his enduring intellectual and political challenge. King calls on us to think and argue publicly about the crises of our present, and collectively determine the broadest range of nonviolent coercive powers at our disposal.

“Our very survival,” King wrote in Where Do We Go From Here, “depends on our ability to stay awake, to adjust to new ideas, to remain vigilant and to face the challenge of change.” The spirit of King is most alive when we embrace these challenges and endeavor, with courage, humility, and a sense of the great sacrifices ahead, to shape a new world out of divine dissatisfaction with injustice.