Philip Jones Griffiths: A Legacy in Photobooks

How book publishing gave Philip Jones Griffiths the freedom to portray the Vietnam War as he saw it

When Philip Jones Griffiths’ seminal book Vietnam Inc. (1971) was reissued in 2001, American writer Noam Chomsky wrote: “If anybody in Washington had read that book, we wouldn’t have had these wars in Iraq or Afghanistan.” The book, published the same year that The Washington Post published the leaked Pentagon Papers, laid out the horrific brutality of the Vietnam War, which built up, along with photographer’s notes and essays, to a searing indictment. He described the effect of war on the country was as if “a mechanised monster had despoiled an innocent landscape”.

Philip Jones Griffiths’ lifelong relationship with Vietnam began in 1966 when, at the age of 33, he left London behind to photograph the war. Previous to this, Griffiths, originally from Rhuddlan, a small village in rural Wales, was living in London as a pharmacist-turned-photographer. Griffiths remained in the war-torn country until 1968, and then returned again in 1970.

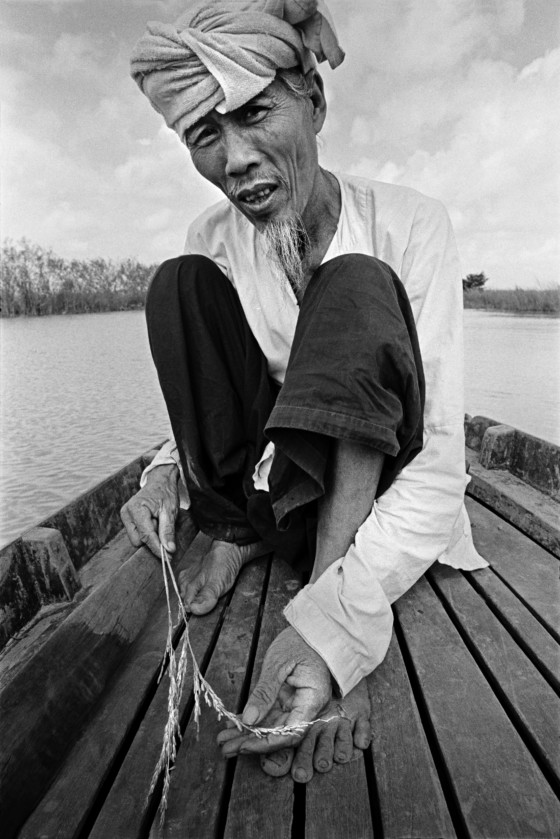

His pictures from the Vietnam War depict all sides of the conflict: American troops with the South Vietnamese and their opponents, the Viet Cong, as well as civilians, who tried to continue with their daily life while the war that would take the lives of an estimated two million civilians raged on.

“Philip was a very different sort of war photographer. In fact, he hated being called a war photographer,” reflected Hannah Watson, publisher of Trolley Books and director of TJ Boulting, during the latest instalment of Magnum Photos Now, a lecture series on photography held at the Barbican Centre in London.

Marking ten years since Griffiths’ death in 2008, Watson was joined at the Barbican event in March 2018 by academic Julian Stallabrass and Griffiths’ two daughters, Fanella Ferrato and Katherine Holden. The latter notes,“a lot of photojournalists in the Vietnam War were there to take photographs for the front pages of newspapers. Philip’s motivation was to make a more durable collection of work. He realized very quickly that the war was such a complex series of events, and he believed a photobook would be the ultimate way of showing and analyzing the nuances of the war. He wasn’t interested in the immediate consumption of the war, and he was willing to throw out the idea of being an objective reporter. He wanted to present a finished, full account of what he believed had happened there.”

"He realized very quickly that the war was such a complex series of events, and he believed a photobook would be the ultimate way of showing and analyzing the nuances of the war."

- Katherine Holden

In looking beyond made-for-front-page images, Griffiths’ work, although graphic and deeply affecting in parts, creates an authored perspective on the war that is more nuanced, more thorough and comprehensive than newspaper clippings could be. “He understood from very early on that a book would be the longest-lasting document and presentation of his thought-process, and he was instrumental and exacting in every aspect of putting the book together,” explained Watson, explaining that the photographer went to Vietnam with the specific intention of creating a book.

“He believed in photography books because he didn’t want his message to be controlled,” Ferrato emphasized. “He didn’t want the media to control him in any way, to control the story or to control the truth. It was his way of staying free.”

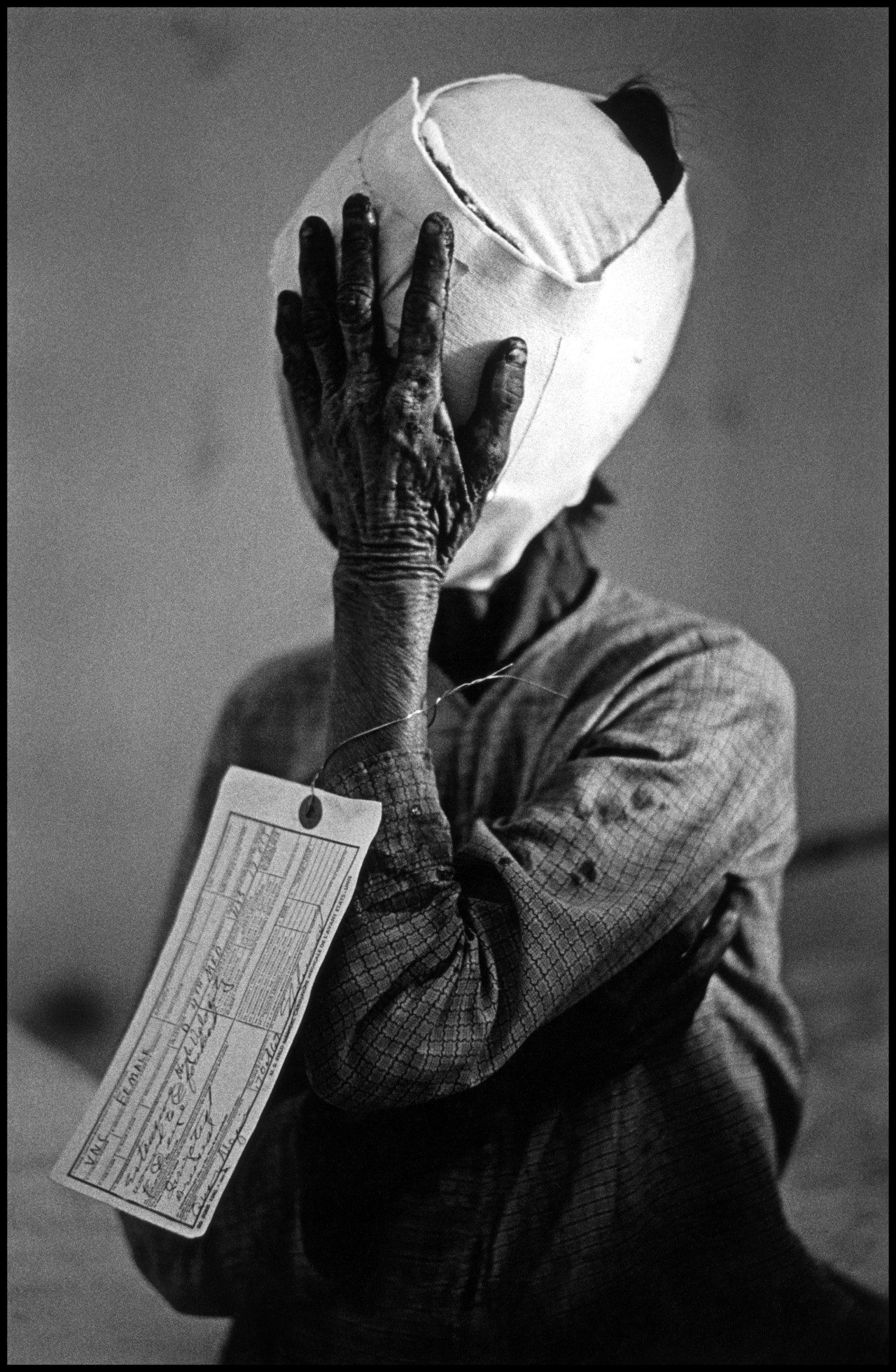

Griffiths’ reporting from Vietnam resulted in the publication of Vietnam Inc. (1971). The images were harrowing and unflinching, featuring charred bodies, obliterated homes, and the now iconic image of a burned woman ghoulishly swathed entirely in bandages. Her only means of identification is the most impersonal and remote of labels: “VNC female”.

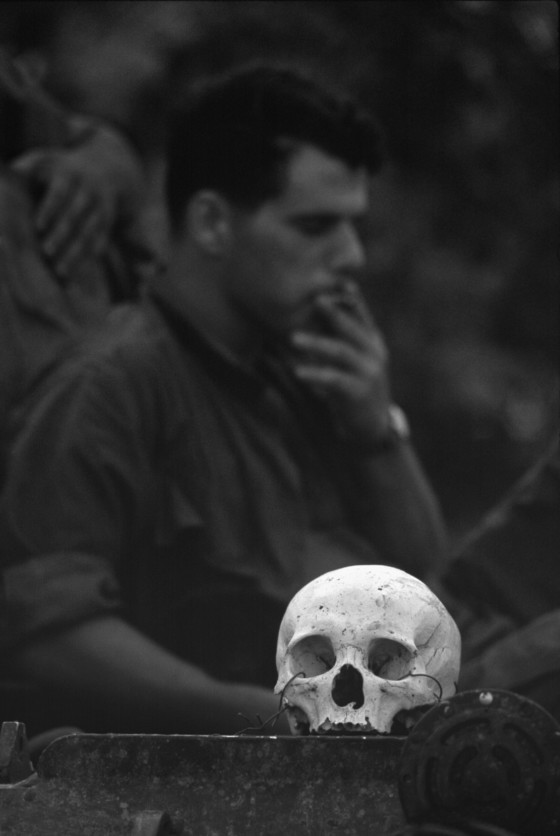

“They were,” Stallabrass says, “amongst the bleakest and most disturbing of the war. It’s a fascinating and remarkable example of publishing because it has a very concerted view of the war. It’s a highly structured book, with a lot of essays and captions and very careful sequencing of images. It’s a very argumentative book, which is a very unusual thing to find.”

Griffiths was deeply influenced by the humanistic ideals of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Magnum’s co-founder, who thought photography could be of genuine benefit to the progress and wellbeing of mankind. The appreciation was mutual – Cartier-Bresson compared Griffiths’ images to Spanish romantic painter Goya’s iconic The Disasters of War: “ Not since Goya has anyone portrayed war like Philip Jones Griffiths,” he said.

Like many of this contemporaries, Griffiths was entirely self-taught but became a master of the craft of photography. As Stallabrass said during the lecture: “Griffiths was capable of making photographs dramatically and partially lit against large areas of profound darkness in scenes reminiscent of Rembrandt. He focused on the drama of gesture and facial expression, upon a finely considered integration of figures to background, and the articulation of figures across a scene.”

"Not since Goya has anyone portrayed war like Philip Jones Griffiths."

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

Through his unflinching authored perspective on the war, Griffiths aimed to demonstrate its senselessness. The Pentagon Papers, leaked that same year, would corroborate much of what the photographer’s knowledge gained on the ground would suggest – that the war was ‘unwinnable’.

His work was lauded by anti-war figures, such as British politician Tony Benn, who would go on to write in tribute to Griffiths’ work: “It must be some comfort to you to know that your work will outlast all the speeches and posturings of politicians with their spin doctors, and will reveal more about the arguments of our times, than you can get from leading articles or BBC programmes.”

Throughout his time in Vietnam, Griffiths operated with a relative freedom, and was able to document, from the front lines of conflict, American, Viet Cong and civilian experiences. Stallabrass recalled once speaking to Don McCullin, a contemporary of Griffiths in Vietnam. “Philip was always very intelligent,” Stallabrass recalls him saying. “He didn’t put himself in circumstances where he was likely to put himself in mortal danger, but he still got really remarkable pictures.”

The multi-faceted perspective created a deep and nuanced insight into the war that has become much more difficult to achieve in conflict situations in the years since. Wars have changed dramatically since the Vietnam War. Now, to get access to the frontline, journalists generally need to embed with one of the participants, and the potential influence on the perspective of photojournalists’ coverage is obvious.

"“Griffiths was capable of making photographs dramatically and partially lit against large areas of profound darkness in scenes reminiscent of Rembrandt."

- julian Stallabrass

Is the kind of insight gained by Philip Jones Griffiths in the Vietnam War possible in modern warfare, in conflicts such as Iraq, Syria or Ukraine? “It’s very difficult to do it now, but it was difficult to do it in Philip’s time,” Holden explained. “My message is: ‘Don’t give up. Because the world needs photojournalists. Although it may be harder to get that openness, it’s not impossible’.”

Griffiths continued to return to and photograph Indochina long after American troops had gone home. The war, he realized, was far from over for the Vietnamese – particularly for the deformed children exposed to a chemical weapon known as Agent Orange. The resultant book, Agent Orange (2004), became another body of damning evidence of a campaign that left a legacy of disease and mutilation.

"He had a sustained and enduring affection for and sense of commitment to Vietnam, and he wanted that to be expressed in a way that would outlast him."

- Hannah Watson

Towards the end of his life, Griffiths’ thoughts turned to the legacy of the work he had created. In 2001, not long after he discovered he had cancer, he set up The Philip Jones Griffiths foundation. Run by his daughters Katherine Holden and Fanella Ferrato, a role, revealed Holden, they were being primed for from a very young age, one of the most important gestures of the foundation was to bequeath some of their father’s work on Vietnam to the country.

“He had a sustained and enduring affection for and sense of commitment to Vietnam, and he wanted that to be expressed in a way that would outlast him,” Watson said.

When Griffiths died,Ferrato and Holden travelled to the country to fulfil his wishes to have his ashes scattered there, and, while there, they paid a visit to the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City, where their father had donated prints. It is now seen by an average of 5 millions visitors a year. “It’s incredible to think his photography lives on like that,” remarked Watson.

“Two of the people who had been affected by Agent Orange, and whom he had subsequently photographed, met us at the exhibition,” said Ferrato. “It was so moving to meet them, and it made us realize the importance of his work to the country.”

Closer to home, a large portion of the photographer’s collection of prints, negatives, clippings, notebooks and other ephemera has been housed in the National Library of Wales. “It’s so important to let people see and engage with the work,” said Holden, who hopes the work and Griffiths’ life story can inspire others from his home country.

Killing for Show: Photography, War and the Media in Vietnam and Iraq, a new book by Julian Stallabrass, will be published early 2019.

An exhibition of Philip Jones Griffiths work is on show now at TJ Boulting, the gallery of Trolley Books.