The Tet Offensive: The Battle for Vietnam’s Cities

Revisiting Philip Jones Griffiths’ searing account of the moment that opinion on the Vietnam War tipped

Vietnamese lunar new year, Tet, is traditionally marked by nationally-observed, lively, community-based celebrations. In 1968, however, when the Vietnam war had been rumbling on for 12 years, the late January holiday was strategically chosen by the North Vietnamese and communist Viet Cong forces as the date to launch a coordinated attack on more than 100 cities and outposts in South Vietnam, including the capital Saigon. It was an attempt by the North to inspire a rebellion of the South Vietnamese people that would force back the scale of the United States’ involvement.

Although the U.S. and South Vietnamese sustained heavy losses, they did achieve a strategic victory, but the huge number of casualties sustained, and the shocking news coverage that Americans saw, turned public opinion on the war, and ultimately marked the beginning of the slow withdrawal of American forces from the region.

Welsh photographer Philip Jones Griffiths documented the war in Vietnam from 1966 to 1971, and was present for the Tet offensive and subsequent fall-out. His book Vietnam Inc. (1971), which he dedicated to fallen fellow photographers, was published in the same year that the Washington Post broke ground by publishing the Pentagon’s secret papers on decision-making in Vietnam. While the papers included details of government concerns that the war was unwinnable at a time they were publicly positive about the war, Philip Jones Griffiths’ own writing on the situation revealed an insight that seemed to echo much of what the U.S. government would seem to have known.

“To the people of South Vietnam and America, Tet 1968 marked the point when the American involvement in Vietnam lost its credibility. To the American people, who had continually believed the ultra-optimistic progress reports on the war, it was the news from Saigon that destroyed their faith in the honesty of their leaders. To the Vietnamese people, caught up in the battles, it was the final disillusionment,” wrote Philip Jones Griffiths.

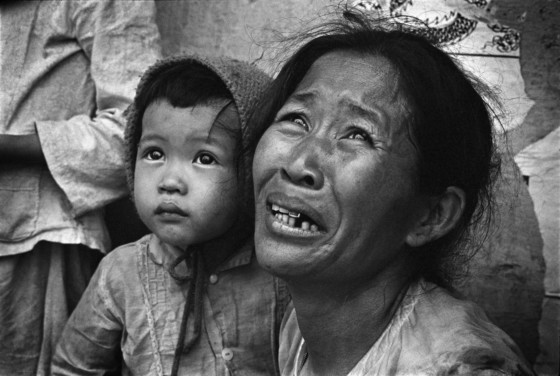

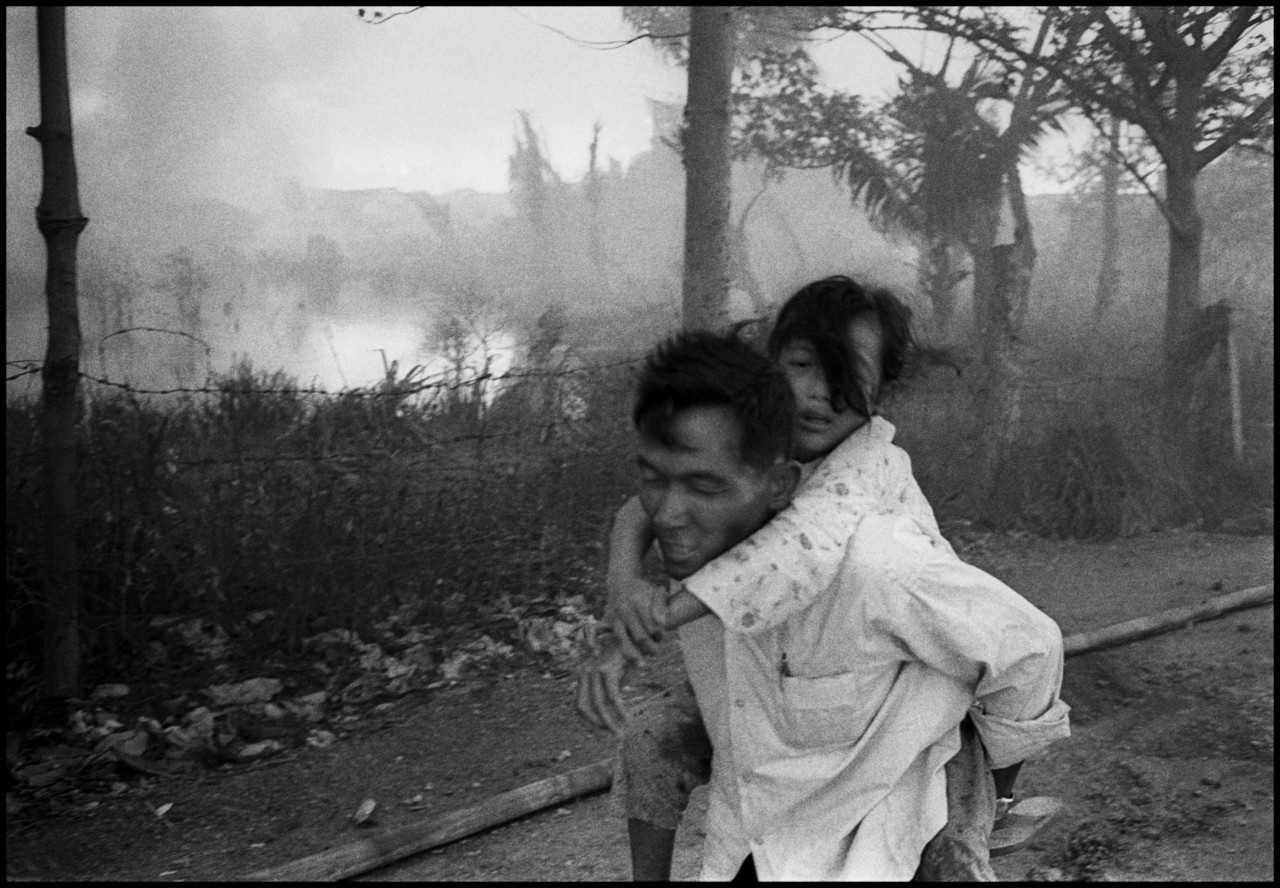

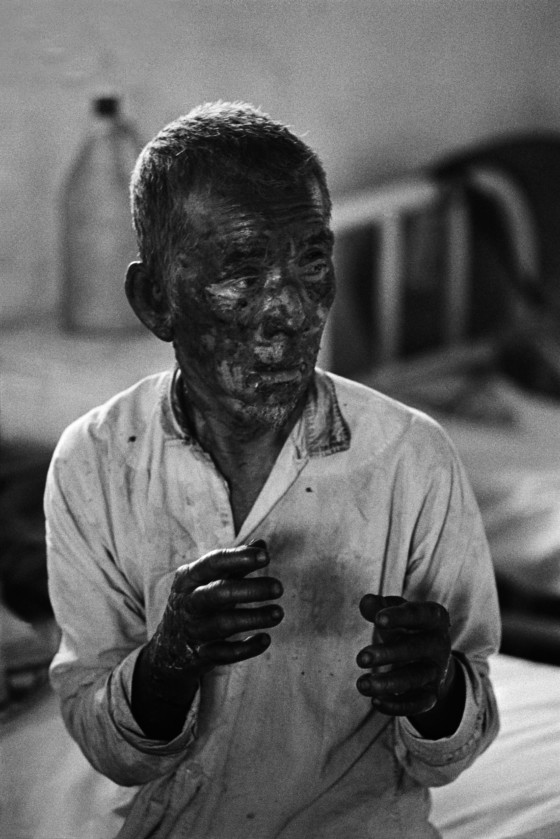

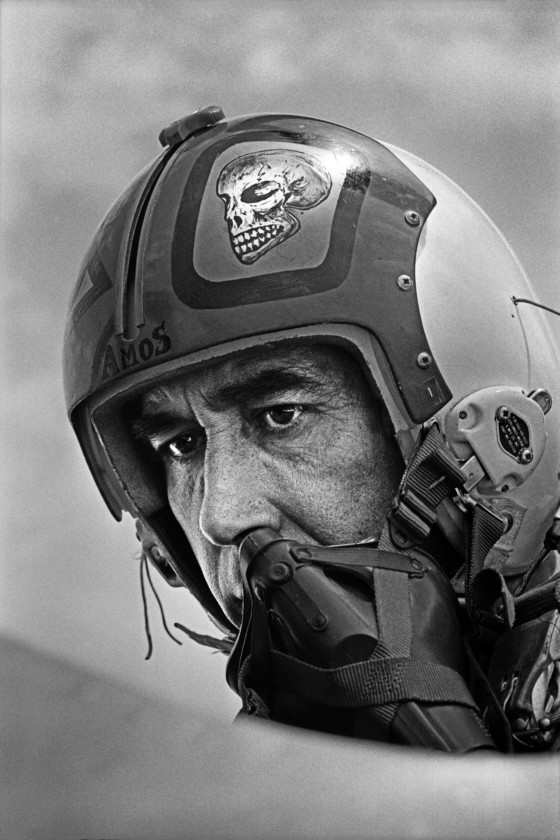

Through his affecting images of war, which depict such devastating scenes as family members with dead and injured loved ones, child victims, fleeing families, and portraits of American military with haunted expressions on their strikingly young faces, he built a picture of the war that only someone deeply entrenched within it could. And his reflective, acerbic writing unpicked the disconnect he identified between what was communicated by the U.S. government and the strategy he saw playing out before his eyes.

"To the people of South Vietnam and America, Tet 1968 marked the point when the American involvement in Vietnam lost its credibility"

- Philip Jones Griffiths

“What the Tet and May offensives did was to negate the central promise on which the logic of the relocation policy was based. This is that the urban centers are haven from the death and destruction meted out to those still living in the countryside. In the spring of 1968 this fallacy was exposed. The sacrifices villagers had made in leaving their ancestral lands for the horrors of city life were in vain. With grim irony, the very same pilots who had bombed them out of the countryside were now bombing them in the cities. The sanctuaries were no more.

That the success of guerrilla warfare depends largely on outwitting the enemy is no secret except, so it seemed, to the American military machine. Not only do the Vietcong rely upon this ignorance to score the more conventional military ‘wins’, but also to manipulate the Americans into unwittingly helping them to achieve their objectives. Never was this more plainly seen than during the Tet and May offensives. It was particularly obvious even to those correspondents in Saigon who’d allegedly ‘got it all wrong about the war due to sitting drinking on the roof-bar of the Caravelle Hotel instead of getting out the paddy fields.’ For the roof-bar of the Caravelle offered a grandstand view of the Phantom jets dropping bombs and napalm on the homes of the only pro-American Vietnamese Saigon.

That the Vietcong should have launched their attacks on the towns and cities of South Vietnam during the spring of 1968 was a logical and predictable step. The degree to which one was surprised by it was directly proportional to the extent one had believed the U.S. information network.”

"The degree to which one was surprised by it was directly proportional to the extent one had believed the U.S. information network"

- Philip Jones Griffiths

However, it was in the detailed captions of individual images throughout Vietnam Inc. that Philip Jones Griffiths revealed the human, and indeed, inhumane, realities of war. One such note refers to a photograph of a woman lying dead in the street of Saigon, killed by U.S. helicopter fire as she ran out from her home. It appears next to images of American soldiers who arrived the next day. Griffiths notes, “The U.S. troops were from the 9th Division and had spent the whole of their tour wading through the mud of the Delta. Some GI’s were amazed to see multi-story buildings, and many were sobered by the realization that they were destroying the homes of people who, in some cases, enjoyed a higher standard of material comfort than they themselves did in America.”

By the time Vietnam Inc. was republished in 2001, it had come to be seen as one of the most detailed on-the-ground reportages from the region during the war. Griffiths’ insight not only humanized the conflict, but was proved to be an accurate assessment of the situation, vindicated by the leaked Pentagon Papers, which corroborated his take.

“Immediately on closing the final volume of the Pentagon Papers, I returned to Vietnam Inc.,” wrote American writer Noam Chomsky in the foreword to a later re-edition. Considering a pairing of images featuring a victim of napalm next to an image of a pilot with a skull on his helmet, he says, “It is hard to look at the distorted face of a little boy of skin and bones, wailing over the mutilated corpse of his mother. Murder at a distance removes the need for elaborate defensive mechanisms.”

“Writing just as the simultaneous publications appeared, one of the finest war correspondents, Gloria Emerson, expressed her ‘deep, angry suspicion and scorn’ for the backroom boys in the White House and the Pentagon, the diplomats and experts, ‘for among them are some stunning lunatics and liars who have done their own country much damage, and nearly killed this one. Her words capture the contrasting images with grim passion,” wrote Chomsky.