On Female Representation

Susan Meiselas addresses how photography can be used as an agent of change in visual representations of women

There has never been a more topical time to talk about female representation in photography, not only the number of female photographers working in the male-dominated photojournalism industry, but also with regards to how women themselves are depicted. Magnum photographer Susan Meiselas has first-hand experience of both of these aspects of the issue. Speaking at a recent event, where she discussed female representation, Meiselas referenced how her own “dwelling” within these two worlds has influenced her work: “The dwelling is the more mysterious place that interconnects you, and the work you find yourself doing.”

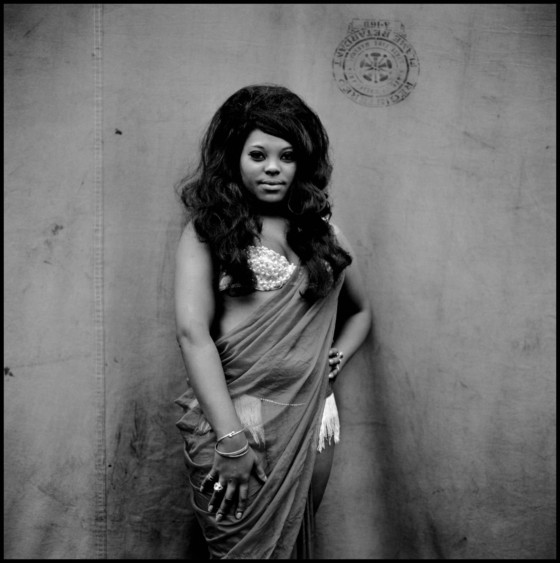

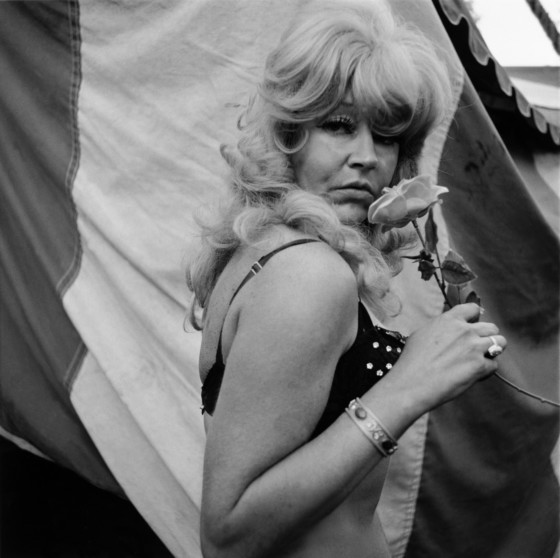

One of the thirteen female photographers who have been a part of Magnum, Meiselas frequently places women at the center of her photographic projects. Over four decades, her wide-spanning practice has evolved across boundaries, from photographing young girls who hung out in her neighborhood of New York, to the women of America’s traveling girl shows of the 1970s to more recent portraits of rooms within a domestic violence refuge in the UK. Throughout, Meiselas has offered an alternative to the default position of the male gaze, asking, ‘Who has the power to look, and why?’

Meiselas spoke at a Magnum Photos Now event at the Barbican Centre in London, in April 2018, along with Amy Sherlock, Editor and Deputy Director of Frieze. Here, we present some of the ways in which Meiselas has made interventions in the photography world to expand the way women are represented, as discussed at the event.

Giving a voice to female subjects

Meiselas is often drawn to those women considered most vulnerable and marginalized in society. While visual representation of closed worlds can often slip into voyeurism, or as Sherlock describes it ‘aestheticization,’ Meiselas ensures the authentic voice of her subjects can be heard. In Carnival Strippers, she explains: “I did a sound collage early on, recording the women, their managers, and clients. It’s the way I felt my photographs should be experienced.” For the photographer, introducing subjectivity into a series is vital. “To mediate is to bring their voices forward, with their own deep knowledge,” she asserts.

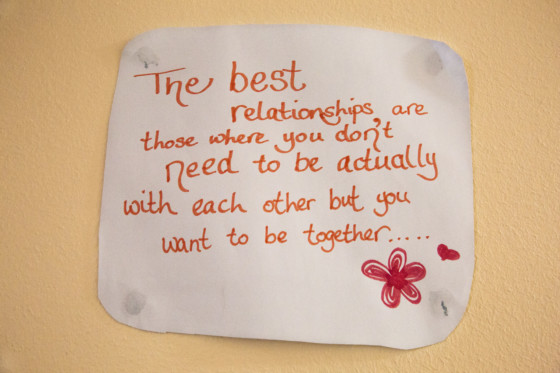

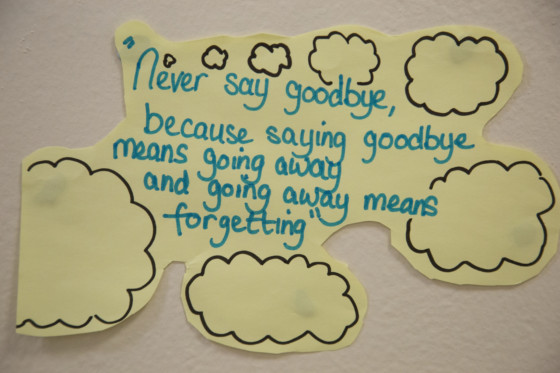

With A Room of Their Own (2015-17), a project that focused on a women’s shelter in the Midlands, UK, Meiselas describes her approach in photographing a protected place of refuge. Establishing trust was vital, not just between herself and the women involved, but also with the institution whose space she entered. “You can’t reveal the place or their identity; these shelters are refuges,” she says.

Meiselas was hyper aware that her photographs caught ‘moments’ in a painful process; “I know how fragile, and how vulnerable the women are.” As she explains. “I didn’t know to what extent the women there, who are transient, were going to be interested in sharing any of their stories. It’s a test of trust.”

The collaborative project included collages and diary notes made by the women and their children, which were created in group workshops. “In each workshop we hoped to create a space where women could participate as little or as much as they were comfortable and willing to commit time for,” wrote Susan when the book was published. The book is much more than a photo documentary publication, it is a printed testament to Meiselas’s characteristic inclusion of of the people she photographs. The women pointed out which corners of the room could be photographed and the images were presented in the book alongside writing and collages they had made.

Changing perceptions

Similar to Carnival Strippers (1972-1975), whereby Meiselas brought her lens to expose a private world filled with sexual desire and complex power dynamics, Pandora’s Box (1995) focused on an S&M club. Although set decades apart, both worked to upend stereotypes, presenting highly sexualised worlds, built on and for the male gaze, from a female perspective, sympathetic to the experiences and conditions of the women working in them.

Meiselas interviewed Pandora’s Box manager Mistress Raven and her female employees. The photographer cut through the constructed sexual fantasy playing out within the confines of the loft, and in a wider context, preconceived ideas about sex and power in society. “The women felt empowered,” she describes. “Mistress Astrid was a musician, for example. They had other lives; this was just their part-time work. It was a case of what do people do, to do what they really want to do. There’s a duality working within themselves. We are all familiar with that.”

Through extensive interviews with the mistresses and through letters from their clients, Meiselas was able to delve deeper into their worlds and offer an insight into Pandora’s Box that challenged contemporary attitudes towards S&M, sex and power. “Some people will say that it is kinky, perverted sex and some that its role play, and others even a lifestyle. Because it’s really not definable except by the person who is engaging in it,” explained Mistress Delilah. Drawn from all walks of life, the majority of the club’s clientele were working professionals — doctors, lawyers, and stockbrokers — unanimous in their willingness to give themselves over to the control of these women.

Experimentations with Control

Meiselas thinks seriously about her responsibility as a photographer, taking into consideration the wider impact both making, and later publishing an image may have on the lives of those featured, and even those outside the frame. Meiselas says what she finds most problematic in photography today “is often the lack of any kind of exchange and understanding with the subject.” She explains that “people take images of anyone, at any time, with no reciprocity. There is a no real sense of subject as presence, rather than an object for one’s self.”

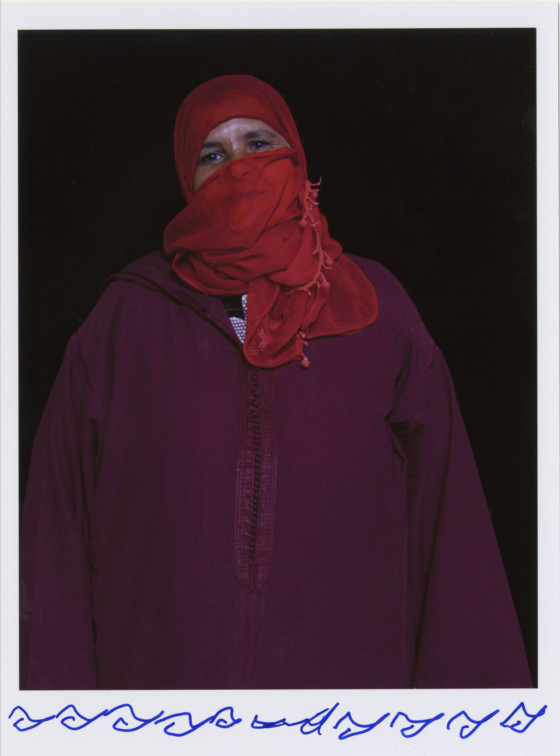

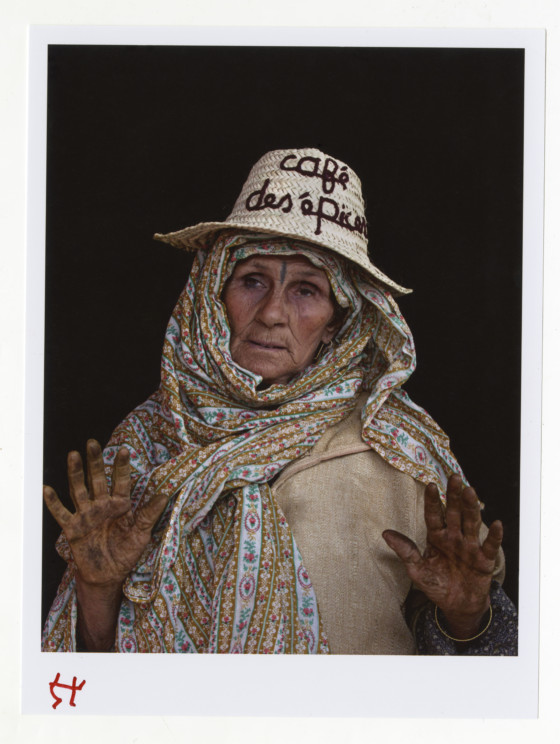

In her project 20 Dirhams or 1 Photo?, Meiselas attempted to give back agency to the women she photographed. Realized as part of a 2013 Marrakech trip with Magnum Photos and MMPVA Foundation, Meiselas tapped into the transaction that takes place between snap-happy tourists and the country’s native women, trading on their image as they sell traditional wares.

Meiselas set up an open air makeshift photo studio on the fringes of a spice market and invited women traders to be photographed there. She then gave them control over what happens to that image; they could choose whether they wanted to keep their picture or receive 20 dirhams (the cost of a local studio portrait) in recompense for loaning their portrait for public view.

“The women in Morocco choose a wide variety of self-representation, fully covered or not, sometimes partially veiled. The question was would they want a picture of themselves made at all? We assume that we know what they feel or want with a photograph. But it is a transaction, they get to choose to interact and participate or not.” Further discussing the issue, she says, “It’s about whether or not they want to be seen publicly, or have their image seen or kept, and if so, kept by whom? Ultimately what value does a photograph offer them?”

Reflecting more widely on the feminist movement, Meiselas said, “Women continue to live in a society that is not the one we would hope to live in; we are still fighting for something fifty years later, that was declared urgent long ago.” “It takes a lot of work to create a more equal world,” said Meiselas, acknowledging her position of both privilege and ongoing responsibility as she added, “That’s why it’s so important to create space for others, to sustain this work and push our ambition forward.”