Bruno Barbey’s Morocco: the Color of Memory

Carole Naggar reflects upon the photographer's use of distance, light and color in photographing the country of his youth

French-Swiss Magnum photographer Bruno Barbey was born in Morocco, and grew up in various parts of the country: Rabat, Salé, Marrakech and Tangiers. It is, “a strangely still, almost timeless land”, Barbey wrote in the introduction to his book, My Morocco, which also includes a text by Nobel Prize winning author J.M.G Le Clézio and his wife, Gémia. The Moroccan author Tahar Ben Jelloun provided the text for another of Barbey’s books on the nation, Fez. Here, Carole Naggar reflects upon the body of work, and Barbey’s unique and beautiful approach to photographing the varied nation.

A collection of fine prints from Barbey’s Morocco work is available now on the Magnum shop.

A woman sits in front of a vibrant orange-painted city wall dotted with hundreds of white palm imprints that make it look like a prehistoric cave. Held in front of her face, her hand echoes their shape, protecting her eyes from the sun, while also reminding us that in Morocco, photographers are not often welcome.

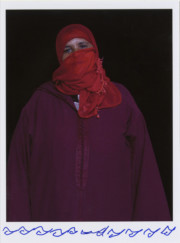

Barbey explains: “It is very difficult to photograph there, because in Islam photography is supposed to bring the evil eye.(…) You have to be cunning as a fox, well organized, and respect some customs. The photographer must learn to blend with the walls. Photographs must either be taken very quickly, with all the risks involved, or only after a very long waiting period.”

Barbey wrote in the introduction to his monograph, My Morocco: “Here, it is sometimes so difficult for a photographer to do his job that he must learn to merge into the walls. Photos must either be taken swiftly, with all the attendant risks, or only after long periods of infinite patience. Such was the price of these images… The memory of Morocco can only be captured with respect.”

In the course of a long career, Barbey has traveled all over the world, but Morocco keeps attracting him like a magnet. Whatever the difficulties inherent to working there, he has chosen to return time and again after a first trip to Fez in 1972. Attracted by the slower rhythm of life and by artisanal and architectural traditions that remain almost untouched in modern times, he often stayed for long periods of time without an assignment. “The Moroccans have so far succeeded in preserving their sense of human society and humanity with nature. They have adapted to the ‘modern’ world while retaining their own culture,” says Barbey. In Morocco, he experiences a sense of freedom and sensual recognition, as if his body was already familiar with the light, the colors and the textures; and he feels in harmony with his environment, most probably because he was born in Morocco and spent his first twelve years between Salé, Rabat, Marrakesh and Tangiers. His Mediterranean physique – Barbey is olive-skinned with dark hair – has probably helped him to blend in and adapt to his surroundings, as did his patient study of Moroccan culture and customs.

"The Moroccans have so far succeeded in preserving their sense of human society and humanity with nature. They have adapted to the ‘modern’ world while retaining their own culture"

- Bruno Barbey

When he started photography, Barbey was shooting in black and white. In 1966, very few photographers at the Magnum Photos, the agency that he had just joined, were making serious use of color —Ernst Haas being an exception, as well as Brian Brake, whose color reportage on the monsoon in India, published in 1960, made a strong impression on Barbey. Cartier-Bresson, for one, was very dismissive of color, maybe because you can’t control it the way you can black and white, or because color reproduction in magazines was then quite mediocre.

"Barbey has seldom, if ever, made portraits in close-up in Morocco. He prefers to shoot his subjects from a distance"

- Carole Naggar

But while working on a Vogue assignment in Brazil in 1966, Barbey began to shoot with color film, pioneering its now prevalent use in photojournalism. He explains: “I had brought a lot of film, including Kodachrome… I started working with this film which is very slow—25 Asa—but is resistant to heat and humidity.” The shift to color proved essential to Barbey’s life and career, and he never looked back. His ongoing work in Morocco, started almost fifty years ago, bears witness to a deep commitment to color, that he has applied to most of his assignments in other countries.

"[Barbey's] ongoing work in Morocco, started almost fifty years ago, bears witness to a deep commitment to color"

- Carole Naggar

Because of his respect of local customs, Barbey has seldom, if ever, made portraits in close-up in Morocco. He prefers to shoot his subjects from a distance as– maybe unaware or dismissive of his presence– they sit, dream or concentrate on daily tasks such as riding a donkey or a horse, goat herding, shopping, picnicking, playing the oud, repairing nets, preparing for a wedding by rolling grain and grilling meats, washing in a medieval hammam; he even managed to get permission to shoot inside mosques, and to catch intimate, tender moments such as a woman combing a small girl’s hair on the roof of their house.

"In Barbey’s Morocco, shadows have as much weight as people and objects, introducing the mystery of another dimension"

- Carole Naggar

In Barbey’s Morocco, shadows have as much weight as people and objects, introducing the mystery of another dimension. In numerous images, he has used the shape of the palm tree, its rough scaly trunk, and supple, finely detailed palms that sway in the wind. In a photograph taken in Tiznit, for instance, the tree’s shadow towers over the silhouette of a man in white djellabah.The darkness traverses his body, covering his torso. In a photo taken in Essaouira, the crenelated shapes of the citadel ramparts projected on a wall ascend over two seated women, with an arch of light framing them. In another street scene, a man is reduced to a dark backlit silhouette, leaving out any details of his appearance. In a striking photograph taken in Ksar el Maadid, a small, hooded, white-clothed silhouette is framed four times in a series of decreasing nested rectangles of light and shadow, as he disappears in the distance of a twisted street that looks like a labyrinth.

In another recent photo, a covered souk’s latticed roof projects stark parallel lines on people’s faces and bodies, giving a sense of both mystery and movement. It reminded me of a passage of Le Clézio’s text on Barbey’s photographs where he describes thesouk, linking color and light with the sense of smell ”What you love more than anything in the souk is the light that filters through the canvas and across the stalls—powdered sunlight mixing with the perfumes and descending to the cold earth.”

Barbey often employs unusual perspectives that flatten the images and merge figures and background. In one case he plunges into the scene from above, with several blurred figures moving around the central round shape of a courtyard fountain as in choreographed moves. In another photo, also taken from above, the deep black fabric of a man’s djellabahand his white shesh, as well as the overcoat he threw on the floor, become geometric elements that merge into the courtyard’s black and white zelliges, the mosaic tiles typical of Morocco. In the tanners’ quarter, clusters of brown and crimson- dyed sheepskins drying on an old city’s ocher walls seem suspended in the air like strange flowers, and the surface becomes two-dimensional, lending the scene a surreal feel. In a photograph of the women quarters inside a home, Barbey uses the flamboyance of the red, yellow, blue and green silk and cotton fabrics and their geometric or flowery designs, merging their folds into the rug’s patterns, as if all the women were fused into a single mass.

Recently, Bruno Barbey has started streamlining his subjects: the people and sites he photographs have become closer to abstractions. It is as if he wants to get to the essence of color. As if traveling through time, he produces serene, musical compositions pulsing with a mixture of longing, memory and emotion, but also suggesting a darker world of secrets behind closed doors. He knows that the modern world is encroaching little by little on the traditional ways of life, and that what he photographs may soon disappear: this is why his images also hold a sense of poignant nostalgia. But in their harmony, they echo what Henri Matisse once said: “All the colors sing together; their strength is determined by the needs of the chorus. It’s like a musical chord.”