Exploring the Relationship Between Nature and Society: Stuart Franklin’s Analogies

The photographer's new book sees him create an non-didactic work that allows the viewer to react to visual metaphor and the vagaries of memory

Stuart Franklin‘s Analogies, newly published by Hatje Cantz, is a continuation of the photographer’s exploration of how we react to visual cues and metaphors in landscape and naturalistic forms, and how man has impacted nature over millennia. From anthropomorphic rocks, to abstracted vistas, twisted trees and the ancient landscaping of pagan religious sites – humanity’s visceral reactions to images allow us to find the familiar in images left open to interpretation.

Signed copies of Analogies are available now on the Magnum Shop.

There are photos in the book spanning the globe, what unifies this disparate assortment of places in the work?

I see this work really as a continuation of my last book, Narcissus, in the making of which I was liberated from all expectations and looked hard at the landscape, mostly in Norway. That was an attempt to try and figure out what it was I was responding to in the landscape. It became clear to me that I was being driven to forms and things that were part of my deeper memory – either conscious or subconscious. Memories of things in the landscape. So, I carried on working in that vein. This book is a development of that. It’s a very honest search for a kind of poetry about the relationship between nature and society.

I am trying to keep the work very open. That is something I have recently understood from reading the thesis that Umberto Eco wrote: The Open Work. The idea of which is that a work should really speak to the viewer, and allow that viewer or reader to tell his or her own stories. In this case, about the images. So, the photos aren’t didactic. They aren’t waving a flag, or trying to tell you what to think or what to believe. But they hopefully allow you to reflect, wonder, or dream.

You mention in the book the idea of “landscape unshackled from place”.

I am using elements that I find within the landscape, not really to talk about place, but to talk about form and images. And this isn’t new. Faye Godwin was doing the same thing when she was working with the writer John Fowles in the Scilly Isles. Several photographers in the United States – from Edward Weston and Tina Modotti to Aaron Siskind and Minor White – were all exploring metaphor in images of natural forms.

Going further back, in 1928 Walter Benjamin – when writing his first piece on photography – reviewed a book of photos of plants. He began to see how the forms of things like curled up fern fronds were reminiscent of an archbishop’s staff, and so on. He described these ideas as ‘hissing up’ like a geyser, these reactions from below the surface, to images. I just followed this idea.

"I am using elements that I find within the landscape, not really to talk about place, but to talk about form and images"

- Stuart Franklin

And what of the more obviously sculpted or man-made subjects in certain photos, how do they fit alongside or interplay with the comparatively pristine landscapes?

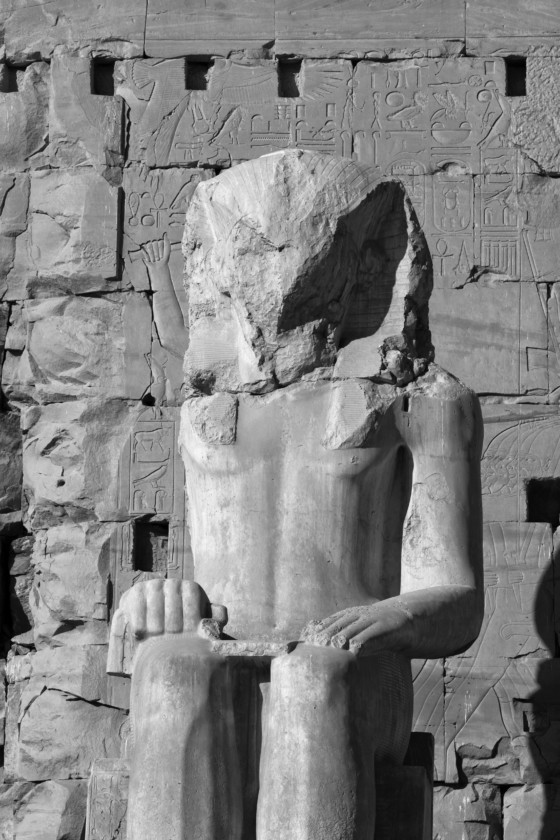

When I came to Egypt what was interesting was that you had these very figurative statues in the landscape which had become weathered. They became, or rather they returned to, their core – to their rocky elements. Then on the other hand you have other forms in, say the Atlas Mountains (and I could have photographed the same thing in the Lut Desert in Iran) where natural structures are being weathered into strange, almost recognisable or decipherable forms.

Mix all of that in with menhirs and standing stones all over Europe – which have the hints of early pagan worship and of a certain attention to the sun and stars, lines of energy – and you have an idea of the complex mix of things that I was dancing around with in making this book.

" Even in places where humans aren’t, say in a photo of sinuous branches , the image invokes in me the idea of dancing figures"

- Stuart Franklin

A number of the places in the book have those hints you mention, of ancient man’s influence and worship. How does the tracing of humanity tie into the book?

I think in most of the images there is the trace of humans… In virtually all of them I suspect. Maybe there are one or two from Norway where that is less the case. But generally there is a touch of human presence in every picture. And, even in places where humans aren’t, say in a photo of sinuous branches , the image invokes in me the idea of dancing figures.

There are images of bending trees in Białowieża Forest, in Poland, which look almost like calligraphy. The reason I shot those trees was that it looked to me like Arabic calligraphy. When I showed that photo to people in Oman they said, “Oh, yes! That’s the letter ‘e’”.

I am fascinated about images, form, and the places they take us to when we look at them. There are images of the standing stones in northern France which are almost human. Looking at them I almost feel that they may stand up and strut off across the landscape.

Do you think there is an over formalised idea of what landscape is, or what it can do? If so, how much is the book a reaction against the strictures of ‘landscape’ as an idea?

Well, firstly many of the pictures aren’t by any stretch of the imagination landscapes. There’s a picture in the book of a painting, for example. But all of the images suggest the idea of landscape. That painting I photographed depicts a familiar trope in the history of art. It is a painting of Susanna and the Elders – which scholars have often read as being voyeuristic – people were interested in painting that particular bible story because it offered the chance of showing a naked women being leered at. In my photograph it’s a further iteration of that process where all we see is the cracks on her torso. And that image became something closer in looks to an aerial or landscape photo. Its that sort of ambiguity that I particularly enjoy. The playfulness of photography, the fact that it is so open.

"When you see these images they throw up other ideas, other thoughts – and that’s what I find most fascinating about photography"

- Stuart Franklin

It is not a book of landscape photography, but it’s a book that explores – in visual terms – the relationship between nature and society. Landscape is a specific genre, at least it was when the Dutch came up with the word in the 17thcentury. It is about ‘a view’. These photographs aren’t that. But on the other hand, in the introduction I do talk about landscape because when you have people looking at rocks in Yosemite say and describing them as ‘cathedrals’, there’s that interesting overlaying of a very human idea onto the landscape. Or take ‘Monument Valley’, it’s just rocks, but it has been humanised, and in some cases there’s also a Christianising of the landscape. These layers of pre-text or thought that come with particular landscapes interest me also.

The word ‘analogies’ is about comparison. That’s what I found interesting, when you see these images they throw up other ideas, other thoughts – and that’s what I find most fascinating about photography. As John Berger said, photographic images are discontinuous – they leave you wondering…