España Oculta: Hidden Spain

Cristina Garcia Rodero recalls befriending postmen and bakers to access remote Spanish villages, documenting their rites and traditions, and the disappearance of the hidden Spain that she loved

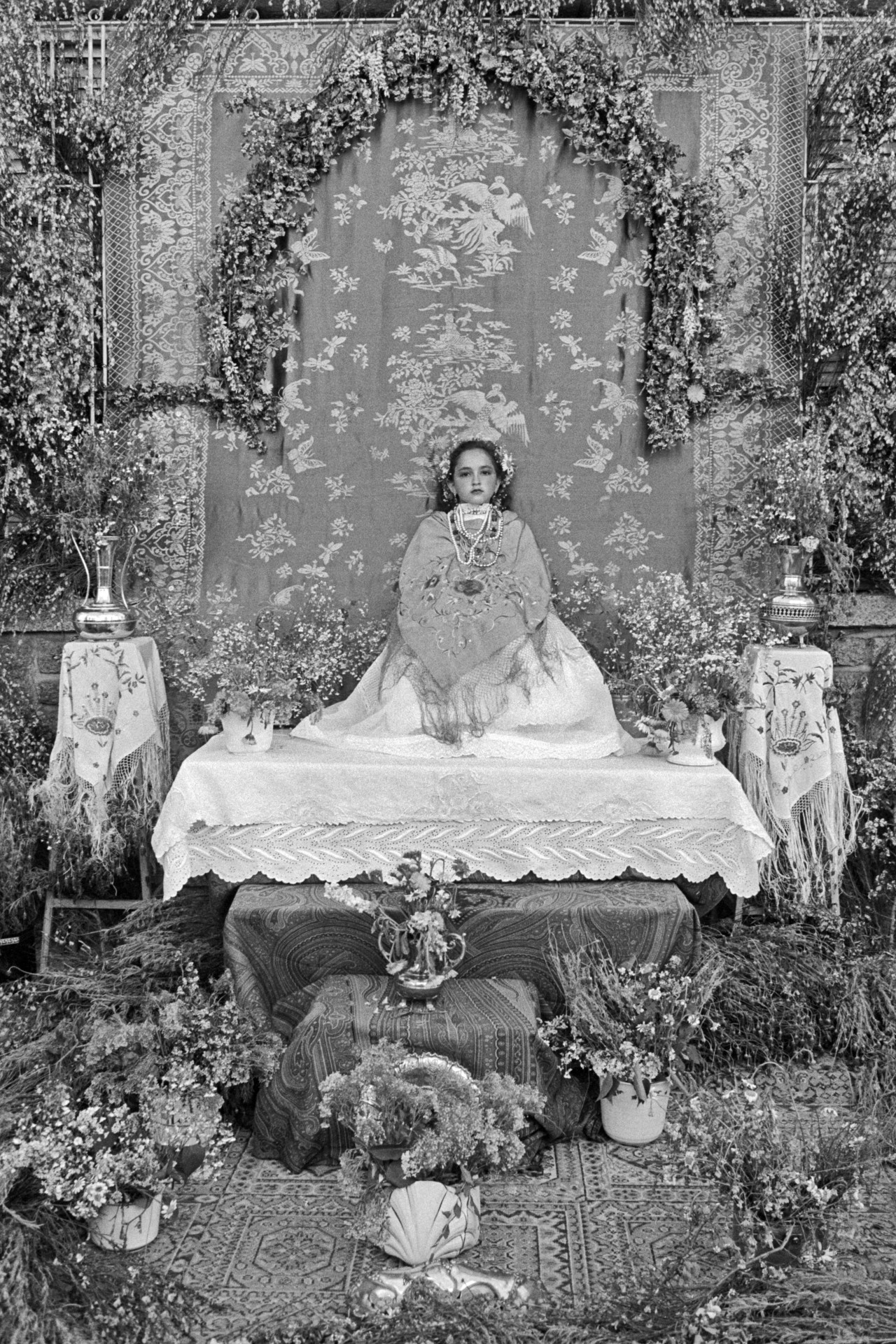

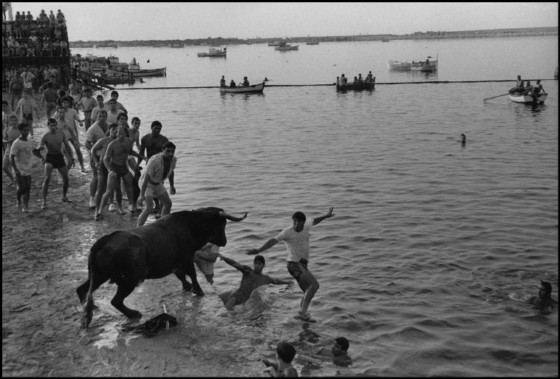

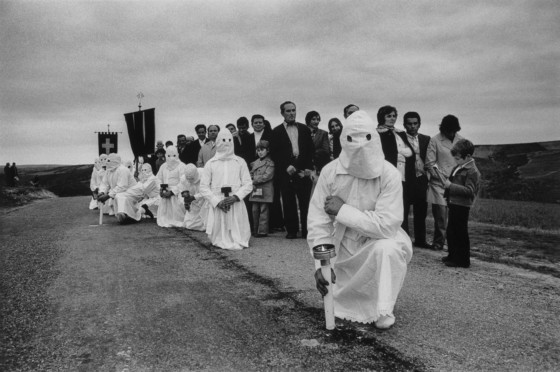

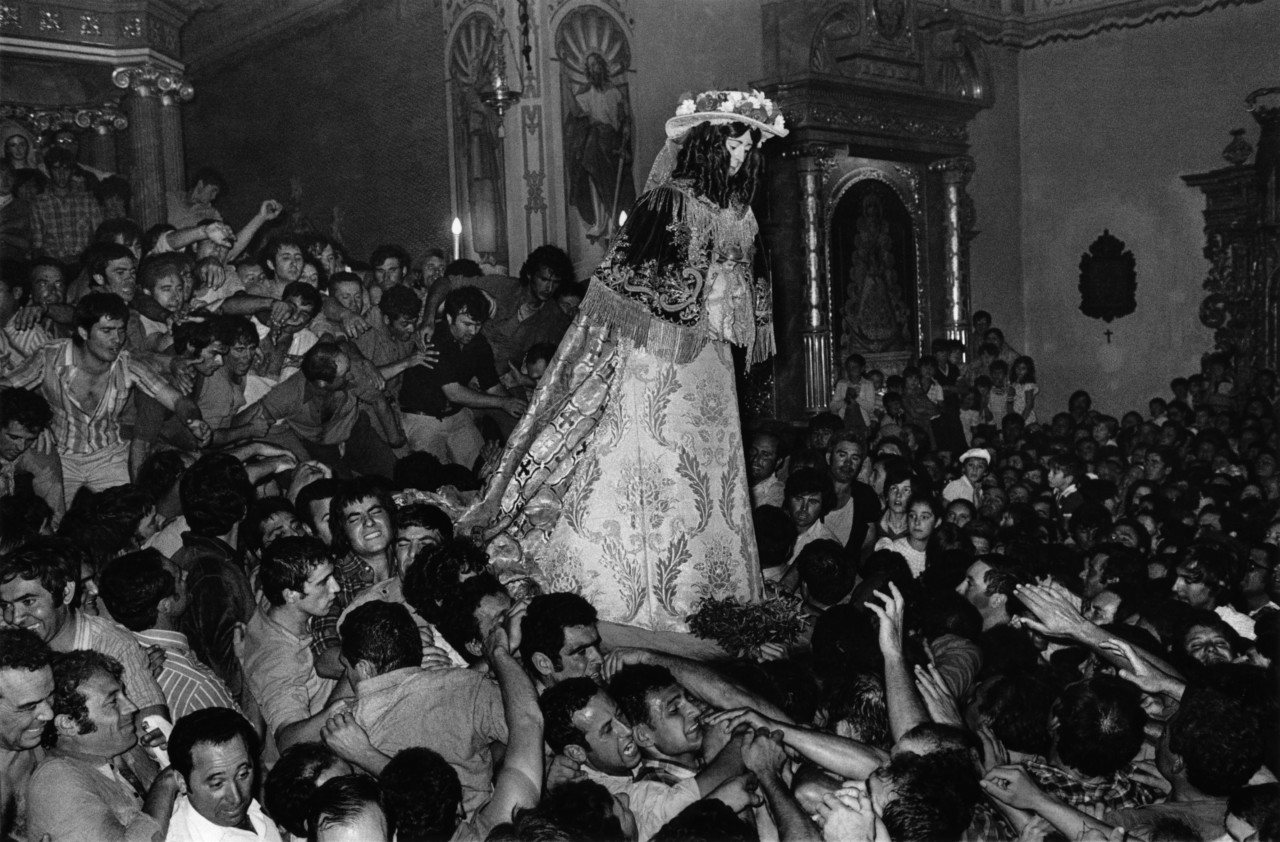

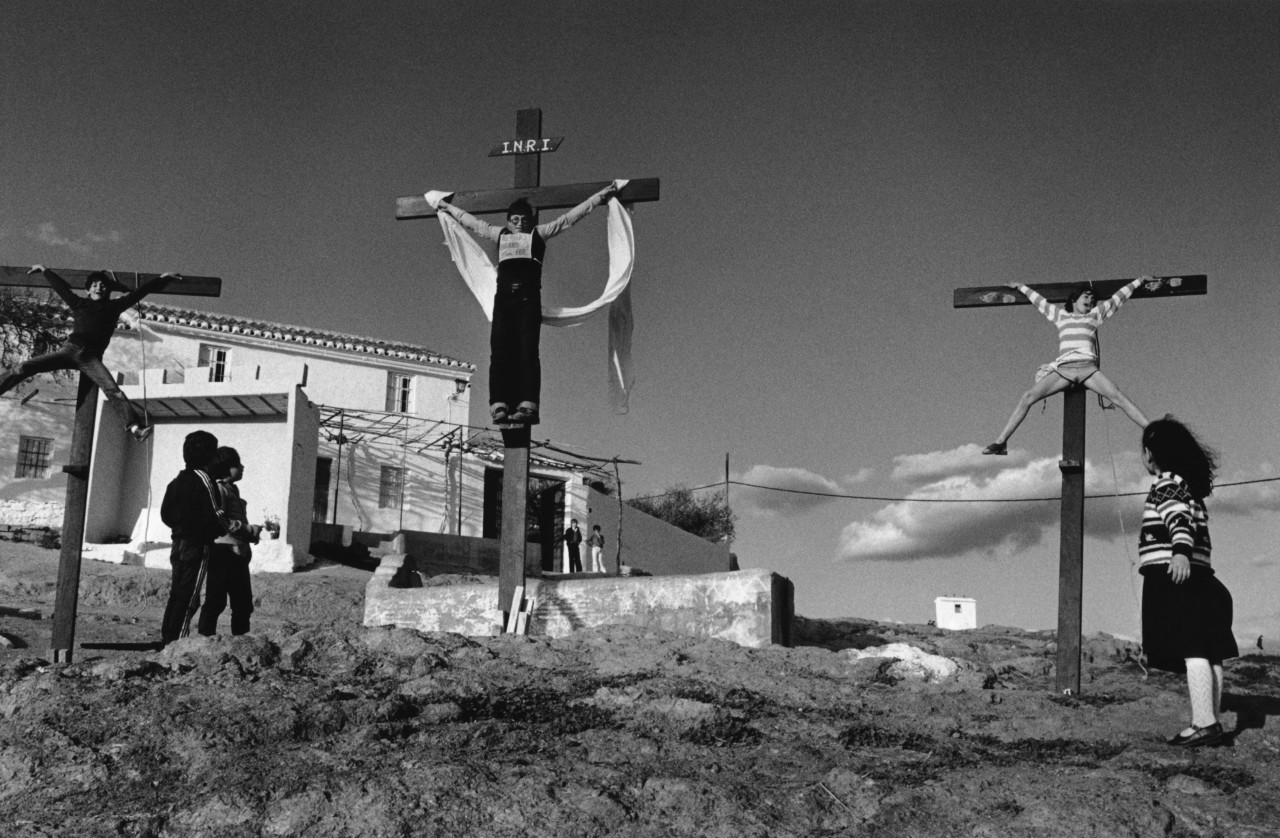

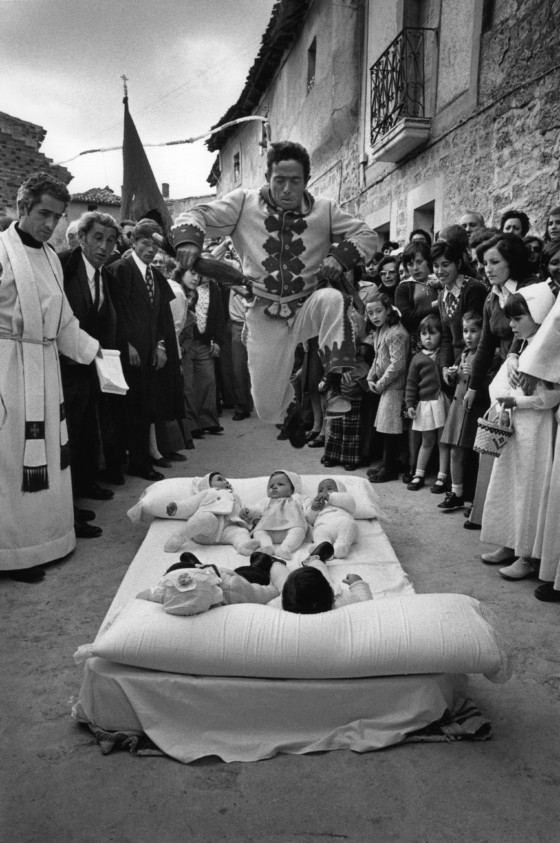

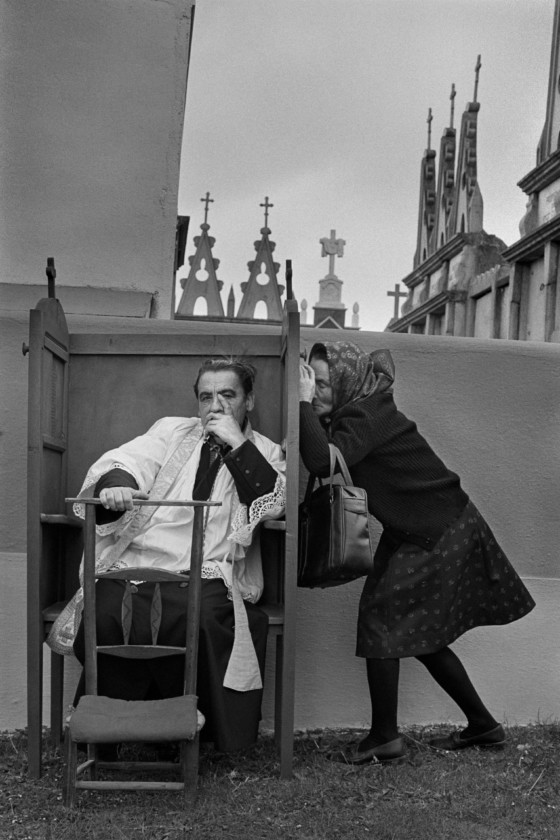

When Spanish photographer Cristina Garcia Rodero went to study art in Italy, in 1973, she fully understood the importance of home. Yet her time abroad formented a deeper interest in was happening in her own country and, as a result, at the age of 23, Garcia Rodero returned to Spain and started a project that she hoped would capture the essence of the myriad Spanish traditions, religious practices and rites that were already fading away. What started as a five-year project ended up lasting 15 years and came to be the book España Oculta(Hidden Spain) published in 1989. At 39 years old, Garcia Rodero had managed to compile a kind of anthropological encyclopedia of her country.

The work also captured a key moment in Spain’s history – with Spanish dictator Franco dying in 1975, and the country commencing a period of transition – something that would come to have a huge effect on the way the nation’s cultural traditions and rites were experienced and performed from then on.

Here, in conversation with Irene Baque – a Spanish documentary film maker living in London – Garcia Rodero reflects not only on how much Spain has changed, but how her passion for photographing rituals and traditions around the world has been affected by globalization, and the Instagram era.

A selection of the images from this story are available as silver gelatine fine prints on the Magnum Shop, here.

You received a scholarship to study photography, in Florence. How did that period feed into the start of the project that would eventually become España Oculta?

I had just finished my BA in fine art and went to Florence to study photography at a school that was, quite honestly, bad. But the lack of teaching there encouraged me to get out on the street, to start making reportage work alone.

The project was born of loneliness. Loneliness which made me think a lot about home. I was yearning for Spain. And I was trying to discover and to learn more about my home country. Through this research I found out about some of the more popular festivals. And with that I discovered a world that was for me so rich, so strange, so mysterious, so happy, so absurd, so ridiculous, so great, so creative, so violent. There were so many things existing at the same time in our traditions, I was surprised that nobody had dedicated themselves to portraying them already.

I thought at the time that I could do something in five years, but it took me 15 in the end. The more I researched, the more I found. And it became a challenge for me, to discover these hidden traditions, to make them well-known, to make ensure they didn’t get lost to history.

"Phone operators - who were all women - became my friends. They would put me in touch with the relevant local councils, the police stations or the small bars in these villages"

- Cristina Garcia Rodero

Considering the sheer amount of festivities and lesser-known traditions that Spain has these days – in every village and town – I can’t imagine what a challenge it must have been for a young woman in her twenties, during a dictatorship and without a resource like the internet, to go and find them.

Finding the information became a real obsession. During those years, any person that would sit next to me on the train or on a bus I would speak to, asking: “Excuse me sir, where are you from? Are there any traditions or festivities in the town where you are from? What about the villages around it?” I asked the same in bars or at any shop I went into. It became truly a necessity for me to find and document these traditional aspects of Spanish life.

Phone operators – who were all women – became my friends. They would put me in touch with the relevant local councils, the police stations or the small bars in these villages who would in turn inform me of upcoming festivals. There often weren’t even taxis that would take me to these villages. I had to befriend postmen and bakers, who would drive me from the nearest big towns to these smaller places. My greatest informants were truck drivers, the homeless, and of course summer fair organizers themselves.

"We were all very conscious that we were privileged witnesses, that the Spain we were in and that we were seeing was about to change"

- Cristina Garcia Rodero

So, this in-depth anthropological study became my life. I wasn’t that aware of the treasure that I was creating, I only cared about the work and effort I had put into it. I didn’t want to miss any small detail – for me everything was important.

I wanted to make our traditions, our festivals, our rituals known. I wanted to show our past. But also, I wanted to reflect our present and our future. Alongside some others who were working documenting these festivities alongside me, we were all very conscious that we were privileged witnesses, that the Spain we were in and that we were seeing was about to change. We knew we had to document both the change and what had preceded it.

"Reportage is a school of life. Your learnings are based on errors and mistakes"

- Cristina Garcia Rodero

Photographically speaking, what was your approach to the project? What moments within these festivals did you want to capture?

In terms of approaching the shoots, I liked to photograph when the day was almost over, and people had relaxed a bit more. When they’ve done their duties and they feel satisfied about their work. Either that, or I like to photograph when they are getting ready and they are distracted or unaware of me. That’s when I could portray the real hidden scenes or family moments. These sorts of images may of course not fully represent the festival or tradition in question, but I feel they speak way more about the human beings involved in them.

When shooting, what was your position towards the environment? How did you find having to navigate among large masses of people? Did these situations present you particular difficulties?

My background at that time, photographically speaking, was in making portraits and I had no idea what reportage was, but festivities meant movement and action. If I wanted to shoot those moments I had to be quick. So, I learnt on the job what reportage was. I learnt to quickly change lenses, what my position should be to not disturb others, to respect the people and events without missing out. Reportage is a school of life. Your learnings are based on errors and mistakes.

"The camera helps you, but the engine is your heart or your head. Having silver cutlery is not gonna make your food taste any better"

- Cristina Garcia Rodero

Festivities and, for me, especially festivities in Spain, are all about color. Why did you decided to shoot in black and white?

Coming from my fine art background, color was fundamental for me. But, I felt that this project needed to be made in black and white because to me it is more expressive. It has less creative elements in it. It takes you away from reality, it gives you a sense of mystery and a poetry that one does not get with color. When you shoot in black and white, the picture has to be good or is useless.

During the dictatorship the country closed its doors to the rest of the world. Foreign magazines and newspapers didn’t reach Spain and American movies would get dubbed and censored. Art wasn’t something one was encouraged to pursue. How did you get the training and cameras?

I was very ignorant, I barely knew anything about photography. I tried to buy photography magazines, but it was really hard to find them in Spain. So, I self-taught with the help of courses I took by post.

I was living in Madrid with my sisters and was teaching fine art during the week. I invested the earnings from my teaching in my first camera, a Pentax, and some rolls of film. My sisters allowed me to set up a photo lab in the small bathroom of the house, so I could develop my own pictures. And every weekend, bank holiday, Christmas, or Easter, I’d get on the road to do my work.

A lot of people would say to me, why are you using a Pentax? You should be using a Leica or something better! But I’ve always tried to demystify the camera. The camera itself is not going to give you everything. The camera helps you, but the engine is your heart or your head. Having silver cutlery is not gonna make your food taste any better.

"You have to believe in yourself. No one else will. I got laughed at by former colleagues"

- Cristina Garcia Rodero

Considering that you had no training in photography or experience in attempting to do such a big project, how did you become so persistent to carry on with it?

Regardless of the little training I had, I still knew I was able to publish a book and make an exhibition of my work. I knew that. It was only a matter of time, I told myself, I know I can. You have to believe in yourself. No one else will. I got laughed at by former colleagues that would say: “She won’t last more than two years”…

My aim was to leave great work behind me. In general, all creators leave the work of a lifetime. They have long-term careers full of obstacles. And many people give up along the way, they get tired of fighting. It requires so much sacrifice and so little recognition.

To be honest, I still don’t know where I got the strength to made such a big effort. I had no money, no car, no information. I just knew what I wanted to do.

Your generation has lived through a lot of change. You were born in a dictatorship and have seen the country evolve into what it is today. Tell me more about that transition period and that change.

Franco died in ’75 and Spain started to change. What we were doing, this sort of reportage work, was utterly disregarded at that time because it wasn’t modern. Modernity was looking at what those in Europe were doing, especially France. Arles, the photo festival, was what setting the trends.

The work I was doing was related to what had been inherited from Franco. To photograph those traditions, that side of Spain, was to photograph what Franco had encouraged. So, we were looked down on and brushed aside. In some way that was true, but for me it was much more than that.

In the ‘80s, Spain witnessed an explosion in freedom and creativity. It seemed that everything was there to be explored – one could do whatever they wanted. And then the rest of the world started to get interested in what was happening in Spain.

"I have seen some festivities that have died as a result of their own success - like the Holi in India. People are just going there, to say they've been there."

- Cristina Garcia Rodero

How has that modernity and the effect of globalization affected the traditions and festivities that you once photographed?

Now it’s very complicated to go to some of those festivities and make work. There’s an oversaturation of information, there is press, the local television stations, the tourists… And they are losing thier authenticity, these festivities. I have seen some festivities that have died as a result of their own success – like the Holi in India. People are just going there, to say they’ve been there.

It’s really hard to work at such events these days. Everyone is already taking pictures on their phones. It is an invasion. You don’t know what to do to compose and create a clean image, an image that is not anchored in time, that is as eternal. Because these traditions are eternal, but they are being placed in a time determined by the telephones that are seen in the photos.

I have been so privileged to live in an authentic Spain. They have welcomed me in all villages with open doors. Now you have to give explanations of why you are taking a photo, where is it going to be published. Or sometimes they don’t let you photograph at all. When I return to the sites, and to see the people with whom I have remained in contact, it is no longer my Spain. It is not the Spain that I have photographed. I don’t have that beautiful intimacy that I used to have with the people. It’s been 50 years, half a century, and many things happen!