Hotel Afrique

Dr. Mark Sealy MBE on the post-colonial trauma explored in Stuart Franklin’s study of service workers at hotels across Africa

“The aim of the project is to examine an aspect of contemporary Africa: specifically, the hybrid space between global culture and Africa’s past and present identity,” wrote Stuart Franklin in the foreword to his book Hotel Afrique. The book sees hotels – locations for international business and political meetings, where the world of privilege meets that of the service worker – becoming a conduit for exploring the relationship between the West and Africa, indigenous and globalized culture, and capitalism and community. In his essay ‘Label Cultural Baggage’, also published in the book and presented here, Dr. Mark Sealy MBE laid out the historical and cultural context within which to understand Franklin’s depiction of contemporary Africa.

It’s hard to imagine a discussion about Africa without Europe being part of the equation. The two continents have been in a constant flux and negotiation since time immemorial. However, the enlightened European thinker conveniently forgot to recognize the inhuman and genocidal nature of Europe’s exchanges with Africa. The dark side of European progress, the slave trade, provided much of the human resources necessary for Europe’s development into a full-scale economic and military power. It is estimated that 15 million people were forcibly removed from Africa to fuel Western capitalist aspirations.

The Berlin Conference of November 1884-5 was to be the defining moment in the ‘scramble for Africa’. The ‘formal’ regulation process of European domination over the entire continent was being carved out. For three months Europe haggled over establishing geometric boundaries within the interior of the continent, negating the cultural and linguistic boundaries of the indigenous African population. The misrepresentation of Africa’s indigenous cultures – as backward and savage – is a defining marker of the colonial presence, a literary and visual legacy that has become part of the dominant ideological Western construction of Africa and its peoples today. As one critical observer writes:

“Amongst your characters you must always include The Starving African, who wanders the refugee camp nearly naked, and waits for the benevolence of the West. Her children have flies on their eyelids and pot bellies, and her breasts are flat and empty. She can have no past, no history, such diversions ruin the dramatic moment.” (1)

(1) Binyavange, Wainaina. How to Write about Africa. Granta 92, Winter 2005.

"The hotel, by definition, has always been a site of privilege"

- Mark Sealy

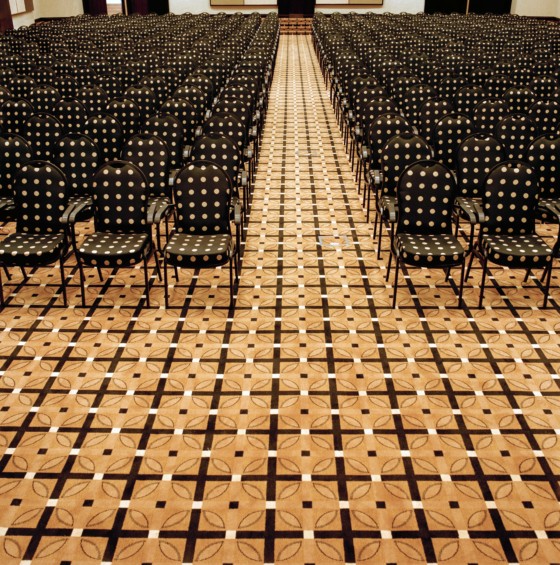

The hotel, by definition, has always been a site of privilege, a space where one is greeted by reception and hopefully a secure welcome, where one expects service. The status of where you stay and how you travel: first class, five star, business class, or standard class has obvious echoes of colonial regimes. Status and privilege also have a huge bearing on how one is perceived or how one imagines one is seen. European perpetuated mythologies surrounding and endorsing hierarchy, functioning alongside the management of fear and the displays of arrogance, form part of the necessary conditions required to maintain colonial power. The ‘wind of change’, however, was unstoppable. By 1960 most of black Africa following Ghana’s lead in 1957, had fought for and won independence.

Both the terms and conditions of independence and the theatre of Cold War politics impacted hugely throughout the new states in Africa. Europe and the United States were determined to influence the political direction of the newly independent African states, and through covert neo-colonial operations managed to hang onto and determine the future political direction of many of those new countries. The divide and rule policy, utilized by the West, was epitomized by the brutal murder of Patrice Lumumba in 1961. Lumumba was the first democratically elected prime minister of Republic of the Congo and a pioneer of African Unity.

"These photographs connote the complex condition of African modernity, framed somewhere between the past and the future"

- Mark Sealy

It’s not surprising, then, that when we look back at this series of photographs, we recognize traces of colonial subjugation and post-colonial trauma. These photographs connote the complex condition of African modernity, framed somewhere between the past and the future, between tradition and progress. The fact that the old and the new Africa can actually exist simultaneously is rarely recognized: a condition that marks the continent as being on the one hand strangled by what Fanon identified as:

“A bourgeoisie similar to that developed in Europe [that] is able to elaborate an ideology and at the same time strengthen its own power. Such a bourgeoisie, dynamic, educated and secular, has fully succeeded in its undertaking of the accumulation of capital and has given the nation a minimum of prosperity… This get-rich-quick middle class shows itself incapable of great ideas or inventiveness. It remembers what it has read in European textbooks and imperceptibly it becomes not even the replica of Europe, but its caricature.” (2)

(2) Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of The Earth. 1961. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 141.

"The Afropolitan knows that nothing is neatly black and white, that to be anything is to be sure of who you are uniquely"

- Taiye Tuakli-Wosornu

And on the other hand, released through the recognition of an Afropolitan perspective of the self, aimed at a future that must unhinge the stereotype, confidently claiming that:

“There is that deep abyss of Culture, ill-defined at best. One must decide what comprises ‘African culture’ beyond filial piety and pepper soup. The project can be utterly baffling – whether one lives in an African country or not. But the process is enriching, in that it expands one’s basic perspective on nation and selfhood. If nothing else, the Afropolitan knows that nothing is neatly black and white, that to be anything is to be sure of who you are uniquely.” (3)

That is part of the tension that resides in ‘Hotel Afrique’. We know that under the lavish veneer there is a deeply troubled and complex body politic that cannot be covered up.

(3) Taiye, Tuakli-Wosornu. Bye-bye, Barbar or, What is an Afropolitan? The Lip No. 5 March 2005 (www.thelip.org)

Explore more stories on how society holidays on Magnum here.