In the Camps

Erich Hartmann’s work documenting the crumbling artefacts and remnants of Europe’s concentration camps

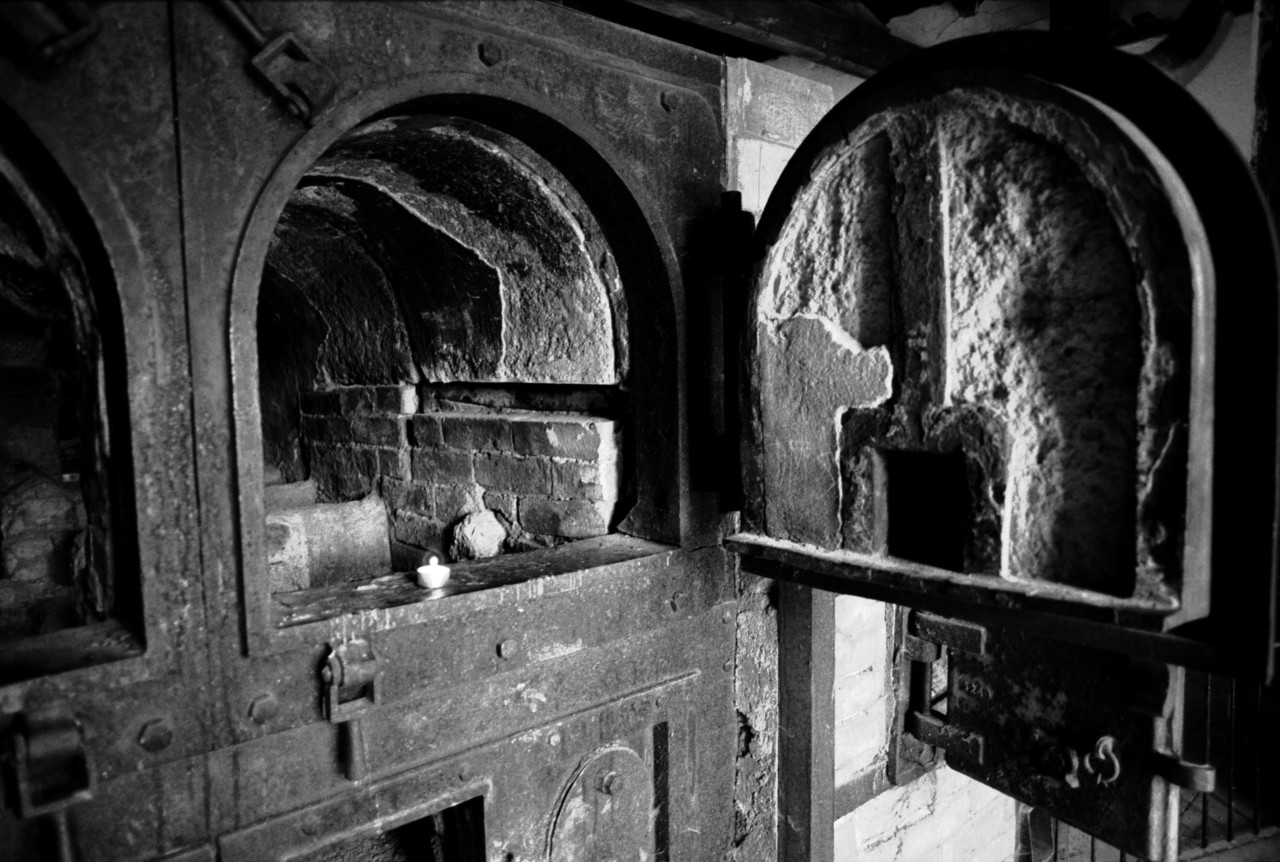

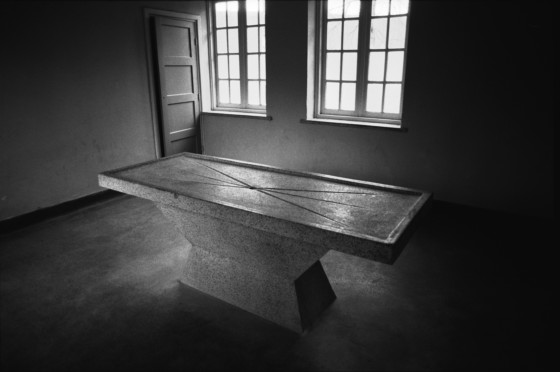

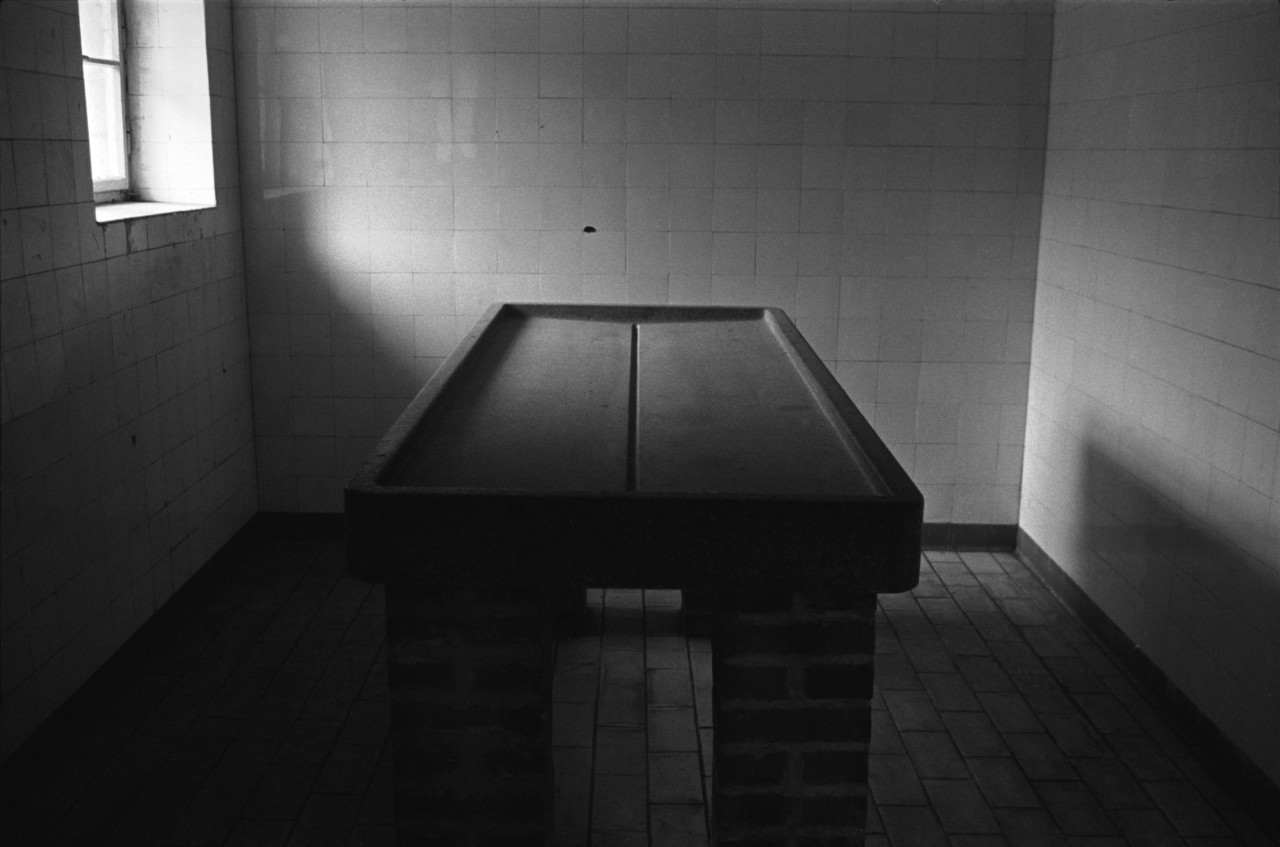

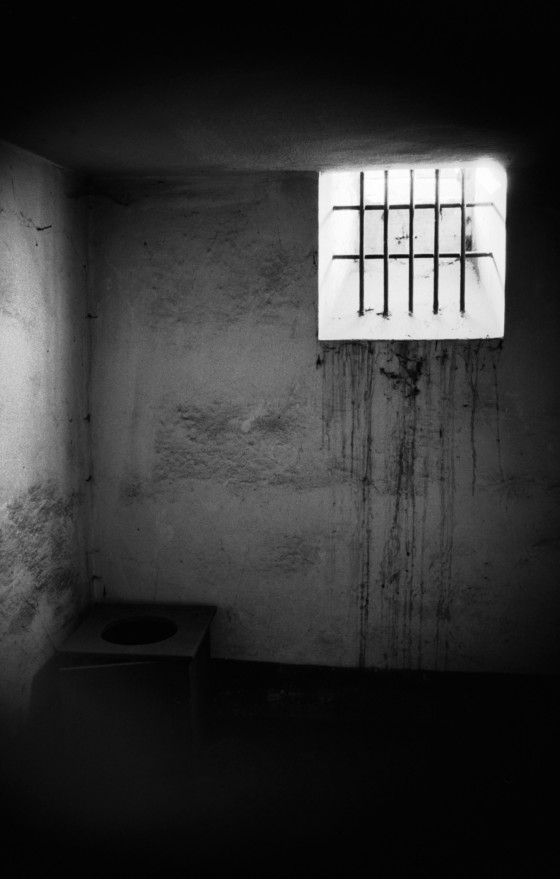

After escaping Nazi Germany in 1938 along with his family, Erich Hartmann served in the US Army during the liberation of Europe. For some time he felt that through his role in those events “whatever debt [he] owed those who had been tortured and killed there had been paid”. Yet over time the feeling that he needed to return to the concentration camps, as a photographer, grew. Finally – near what he described as the end of his working life as a photographer – he did so, photographing 22 camps before their original artefacts and structures crumbled to be replaced by educational replicas and museums.

Here, to mark the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau and Holocaust Memorial Day, we reproduce an unedited version of Hartmann’s essay from his 1995 book, In the Camps.

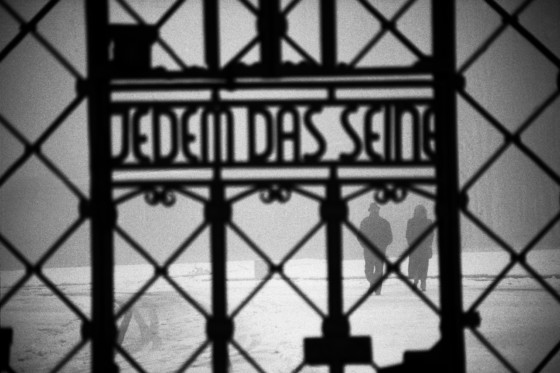

In times past the word Dachau referred to the picturesque old town a short train ride from Munich, the nearby moors long a favorite motif of landscape painters. Beginning in early 1933, when I was a teenager, shortly after the Nazis were elected to power in Germany and until the end of the war in 1945, Dachau came to mean the concentration camp that they had built on what were the potato fields at the edge of town. Its official name was “Labor and Re-education Facility,” but soon there were whispers, then rumors, and finally eyewitness reports that it was a place of brutality, of random violence and systematic destruction.

Dachau was destined to be the first of many such places, part of a precisely planned and organized system of concentration camps with clearly defined purposes – to eliminate all political opposition to the Nazi regime by means of terror, to use all able-bodied prisoners as forced labor for German industry until they were exhausted from starvation and overwork at which point they would be killed, and, finally, to destroy the spirit and the body of and man, woman, and child decreed undeserving of life according to the racial laws of the self-proclaimed “Master Race”, among them homosexuals, Gypsies, members of charismatic Christian sects, and those handicapped in body or mind. And, of course, all Jews.

I had an early encounter with Dachau whose memory has never left me. I had a small accident in a fall from my bicycle and as I entered the waiting room of the nearby clinic two men were already there, one standing, the other sitting at the edge of the bench. The one standing wore the black uniform and boots and death head insignia of the SS, the other wore the grey-blue striped pajamas and wooden clogs of a Dachau inmate. His head was shaved, his face was gaunt and showed bruises. Neither spoke. I don’t know why they were there. The SS guard looked out to the spring garden, the prisoner looked either onto the floor or, occasionally, also out of the room. They did not look at each other. Once the SS guard looked at me, without interest. In his eyes I saw the calm that comes from the possession of total physical power. My eyes and those of the prisoner did not meet, but I saw in them an emptiness that I had not ever seen before and in his face no expression of any kind. What I saw was the absence of expectation or hope – an expression of nothingness. I was soon called and my knee bandaged and on my way out the two men were no longer in the room. I saw neither of them again: I would recognize the prisoner to this day.

I had heard the phrase “blood running cold as ice”; now I knew what it meant. In that encounter I felt real fear and real terror for the first time in my life. I understood not only in my brain but in my guts what the Nazis were making of the Germany that was my home and that I loved – “an icy hell,” as one Dachau survivor wrote. For a few minutes, even in that clean and antiseptic setting, I got a whiff of what it must be like to be a prisoner of the SS and I realized only later that I had seen the two faces of Nazi Germany – both the faces of death – that of the killer and that of the victim. The Nazis were turning a traditional and often overwrought German romanticism that had produced great literature and art into a worship of death that let loose on their enemies and ultimately on their own a systematic and barbaric order of killing. Death became the main instrument of the “Thousand-Year Reich” and the burden of its legacy to this day.

"Apparently some debts are not easily settled. Over the years and increasingly in the recent past I came to feel a summons to return to the remains of the camps. It did not come suddenly and it was never precise, rather it consisted of subtle, sometimes ambiguous, and always unexpected “messages”..."

-

In the more than fifty years since then that I have lived in the United States I have never found an explanation for why my father was not put in a concentration camp. Like many others who were taken away, he was a middle-class Jew, successful in his work, a lifelong if passive Social Democrat, known and respected in the community. Perhaps he was spared because he had served and had been decorated for his years in the trenches of France as a soldier of the German army in World War I; in the beginning, at least, the Nazis seemed to have a respect for patriotism, even for that of Jews. But if my mother had not had generous relatives in America who enabled the whole family – parents, two boys, and a little girl – to leave Germany in the summer of 1938, none of us would have escaped the camps much longer. Those of our relatives and many friends who could not leave – or would not leave – did not escape the camps and few survived.

I was sixteen when we left Germany, it was a wrench to lose what I had believed was my country and my language, it was difficult to begin growing new roots in a new home – at least it seemed so at the time. But soon, as bits and pieces of news drifted over from Europe, we came to understand that we had been spared a fate that was unbelievable even in the light if what we had experienced between 1933 and 1938: a legally elected German government was making of the country that had produced great philosophers and artists an instrument of systematic terror, brutality, slave labor, torture, and killing that consumed, like a wildfire, millions of innocent people, Jews and many others, in a frenzy of destruction. Eventually there were over a thousand camps and subcamps, a vast and dismal landscape of barbed wire across Germany and conquered Europe.

Not only we and other refugees from the Nazis, but the rest of the world, too, came to know of these deeds long before the end of the war, and soon everyone also knew that the majority of Germans had done little to protest, and very little to defeat the increasingly violent seduction of their own country and the rape of many other countries in Europe. In Germany the phrase “we did not know that they did” is still current and my response still is “how strange that you did not know – we knew what they were doing.” The phrase “we did not want to know what they did” is not often heard.

"Every day that I spent walking through former camps I wanted nothing more than to leave them again as quickly as possible, and every day I was grateful that instead of just being there I had a camera, a machine without feelings of its own, with which to attempt to express what I felt"

-

I volunteered for military service on the morning after Pearl Harbor and had to wait a year to be accepted since I was still an “enemy alien” and classified as a “premature antifascist.” But finally I was inducted and spent three tears in the US Army, most of them in Europe, the usual “Grand Tour” – England, France, Belgium, Germany – and when the war was over and we had won I believed that I had paid off a debt of gratitude to the United States, the country that had taken us in and thus had saved our lives.

Not long after V-E Day, while I was stationed in Augsburg, I drove to the concentration camp in Dachau. By then the many dead that had been found piled up on the ground by the liberating Allied troops had been buried and most of the barracks had been emptied and leveled to stop the further spread of diseases. As a part of the makeshift display for visitors in one of the remaining barracks a prisoner’s uniform had been put near the door, with a sign hung from the neck that said “ICH BIN WIEDER DA,” “I AM BACK,” recalling prisoners who had tried to escape and been recaptured, made to stand with that sign hung on them on the parade ground, then been slowly and systematically beaten to death in the presence of the entire prisoner population that had been assembled for the purpose.

I remember feeling that the sign also referred to me, that I was once again where I had been born, returned from my safe new home, confronted with what had happened to people like me. I knew then that the terror I had felt when I saw the prisoner and the SS guard in the clinic had been an accurate omen of a fate that could have befallen me as well, and that I did not know why it had passed me over. For a long time afterward I believed that by having served in the liberation of Europe I had also helped to stop any further suffering and slaughter in the camps and that whatever debt I owed those who had been tortured and killed there had been paid.

But, apparently, some debts are not easily settled. Over the years and increasingly in the recent past I came to feel a summons to return to the remains of the camps. It did not come suddenly and it was never precise, rather it consisted of subtle, sometimes ambiguous, and always unexpected “messages” such as what happened a few years ago when my son and I were in Munich at the same time on separate work, a rare occurrence. We decided that afterwards we would take a short holiday together, “but first,” he said, “show me the camp at Dachau,” and that is where we began the journey. Like me he prefers solitude to tour guides, hence there was little talking or explaining and as we left he took my arm and said, “I was thinking that I might have lost you right here.”

"I knew that my being in the camps or photographing in them would bring no one back from the dead or ease the suffering of any survivor. I simply felt obliged to stand in as many of the camps as I could reach, to fulfill a duty that I could not define and to pay a belated tribute with the tools of my profession"

-

Finally I came to the realization that now, toward the end of my working life as a photographer and close to the fiftieth anniversary of the liberation of the last camps, the persona and the photographer had to come together as never before to make images in what remains of the camps and of what there is still to be seen in them. I had photographed in some camps occasionally and casually during earlier trips to Europe, but now it was to be a journey undertaken for this purpose alone. I had no illusions; there would be nothing of fact that I could add to the existing voluminous documentation of the camps, and I knew also that my being in the camps or photographing in them would bring no one back from the dead or ease the suffering of any survivor. I simply felt obliged to stand in as many of the camps as I could reach, to fulfill a duty that I could not define and to pay a belated tribute with the tools of my profession.

In the middle of last winter I journeyed to the camp sites and to the other places which are shown in this book. The weather was fitting – nearly always overcast and wet; often there was snow on the ground and sometimes heavy fog in the air. The days were short and most of the time it was half dark even at noon. In the stillness I heard little except the barking of dogs, the crunch of my shoes on the ground, sometimes the throb of my pulse. Even when my wife was along it was voyage of silence; words are of no avail there. Visitors, if any, were few – it was the season of holidays and school vacations.

I was surprised at the intensity with which even after so many years the camps seemed still inhabited by the echoes of the dark and bitter past. Every day that I spent walking through former camps I wanted nothing more than to leave them again as quickly as possible, and every day I was grateful that instead of just being there I had a camera, a machine without feelings of its own, with which to attempt to express what I felt. I am convinced that I would not have survived in any of the camps.

"The passage of time is unstoppable. The number of survivors diminishes every day and soon there will be no one – neither victim or perpetrator – who was there"

-

The journey took a little over eight weeks. In Poland, where we had never been before, we had a driver / guide / interpreter; we travelled to Theresienstadt by night train from Germany to Prague and drive the rest of the way; elsewhere I rented cars as I needed them. There were occasional days of housekeeping and rest, even of celebration. We spent New Year’s Eve in Hamburg in the quiet lounge of our small hotel in the company of two other couples presumably also far away from home and watched over by a gentle bartender with a generous supply of the traditional crullers and Sekt, the German champagne. If there was any music it was so soft that it did not disturb and there was little talk; each person was respectful of the others’ private thoughts. Mire were predictable – I had spent Christmas alone in a thick and cold fog in the Buchenwald concentration camp before driving to the vicinity of Bergen Belsen in the early dusk; at this moment I was in a festive place in the comfort of beloved company; in a day’s time we were leaving for the death camps of the SS in Poland, not only designed to do away with the Jews and Gypsies and homosexuals of Europe, but designed also, later on, to get rid of the millions of Soviet prisoners of war whom the German army expected to capture, and later still, to empty the fertile Polish and Ukrainian plains of their inhabitants so that German immigrant settlers would have “Lebensraum” once Germany had won the war. I felt warm and cold at the same time, I was at my ease and on edge at the same time, it was a breather between the unjoyous memories of weeks past and the anticipation of weeks to come.

"Before the abominations of Treblinka, of Sobibor and Belzec, of Dachau, Birkenau, Chelmno and all the rest, one can feel anger, sorrow, pity, rage, nausea, anxiety for the human race, but in the rose garden behind the Bullenhuser Damm School one can only weep"

- Ruth Bains Hartmann

When we returned a month later I thought that I had been to the bottom of the Nazi’s inhumanities but I had not; it was at an obscure memorial in Hamburg not long after we came back from Poland where the full extent and enormity of the Nazis’ deadly rage flooded over us. Ruth Bains Hartmann, my wife, wrote about it in her journal:

Each time one thinks to have looked into the farthest depths of human cruelty, the abyss awaits. After all the horrible things I had seen, all the places of human suffering – at the hand of man – I had witnessed, how could I imagine anything worse?

There is a small rose garden in an industrial area of Hamburg, not far from one of the city’s many canals. Irregularly shaped, the garden’s wooden fencing separates it on one side from a busy highway, on the other from the play-yard of a nursery school where on a wintry morning brightly dressed toddlers splashed happily in frigid puddles until a teacher shepherded them towards less dangerous play.

On the far side of the playground is Bullenhuser Damm School, in the Nazi time a sub-camp of Neuengamme, the concentration camp near Hamburg, now renamed as the Janusz Korczak School, for the head of the Warsaw orphanage who died with his children in the Treblinka gas chamber.

A few days before the end of the war twenty Jewish children were taken by the SS to the Bullenhuser Damm School together with two French doctors and two Dutch men, their caretakers, all prisoners. In November 1944 these children, ten boys and ten girls (the Nazis were ever methodical) aged from five to twelve years, had been brought from Auschwitz to Neuengamme where they were subjected to medical experiments by the SS doctor Kurt Heissmeyer. The children were injected with TB bacillus, making them very ill, then their lymph glands were removed for analysis.

On the night of April 20, 1945, with British troops not far from Hamburg, the SS took these children, together with the four men, to the furnace room in the cellar of the school where they were hanged. Hanged. The youngest ones were five years old.

There were millions of victims at Auschwitz; one struggles to imagine even one million. The reality of these millions of tortured lives and horrible murders can hardly be grasped. In the atrocity of the hanging of twenty young children one’s imagination is vivid. Some of these children were perhaps as young as three when they were taken from their homes in Italy, France, Poland, Holland, Yugoslavia, transported hundreds of miles in filthy railroad cars, separated from their families, transported again, tortured methodically and lengthily and then destroyed, hanged in a cellar. This one can imagine; they can stand for the millions:

Marek James, six years old, from Radom in Poland

H. Wassermann, and eight-year-old girl from Poland

Roman Witonski, six years old, and his five-year-old sister Eleonora, from Radom in Poland

R. Zeller, a twelve-year-old boy from Poland

Eduard Hornemann, twelve years old, and his brother Alexander, nine years old, from Eindhoven in Holland

Riwka Herszberg, a seven-year-old girl from Zdunska Wola in Poland

Georges André Kohn, twelve years old, from Paris

Jacqueline Morgenstern, twelve years old, from Paris

Ruchla Zylberberg, and eight-year-old girl

Edouard Reichenbaum, ten years old

Mania Altman, five years old, from Radom in Poland

Sergio de Simone, seven years old, from Naples

Marek Steinbaum, ten years old

W. Junglieb, a twelve-year-old boy

S. Goldinger, an eleven-year-old girl

Lelka Birnbaum, a twelve-year-old girl

Lola Kugerman, twelve years old

B. Mekler, an eleven-year-old girl

Before the abominations of Treblinka, of Sobibor and Belzec, of Dachau, Birkenau, Chelmno and all the rest, one can feel anger, sorrow, pity, rage, nausea, anxiety for the human race, but in the rose garden behind the Bullenhuser Damm School one can only weep.

The weak winter sunshine picked out the bright green of the early shoots of spring flowers among the sleeping rosebushes. Then a black cloud came over and freezing rain poured down over the garden as I stood there reading the names on the memorial plaques that line the fence.

As the murders of these children can stand for the murders of millions, so can the inscription in their memorial garden speak for all the places of terror and death:

WHEN YOU STAND HERE, BE SILENT;

WHEN YOU LEAVE HERE, BE NOT SILENT.

The passage of time is unstoppable. The number of survivors diminishes every day and soon there will be no one – neither victim or perpetrator – who was there. Soon the entire physical fabric – buildings and authentic objects – will have disintegrated and will have had to be completely replaced by reconstructions, as for instance the seemingly endless miles of rusting barbed wire are already having to be replaced every few years. Hence, the functions of the camp site will change from being mainly places of memory and reminder to becoming mainly museums and educational sites, their physical area to be reduced in many places. Photographs such as these may not be possible much longer.

There is good reason to believe that the function of the existing camp sites will change significantly and perhaps soon. At present their main purpose is to document and to describe what happened there and how. That has been difficult enough because of the Nazi’s often successful efforts to obliterate all evidence ahead of the liberating armies. It is a sanitized documentation at best – what is left of the camps today is clean, where they were filthy when they were in use; now they are quiet, whereas they were filled with noises then – the screams of guards, the snarls of dogs, the sounds of shuffling feet, snoring, coughing, moaning. Today the camps are empty and no trace is left of the endemic overcrowding, lack of water, of heat, or food, and of any of the basic decencies of life that led soon to outbreaks of diseases and epidemics. Many survivors have said that having no privacy of any kind was among the most difficult parts of camp life to bear.

"In Germany [the past] is nearly palpable, the uninvited and often unexpected guest in many phases of public and personal life. The memory of what some Germans did and many Germans chose not to notice remains an irritant, like an open wound that keeps hurting and does not heal"

-

On this journey I realized once more that, even after the many years since the liberation of the concentration camps, the Nazi past has not been put to rest. In Germany it is nearly palpable, the uninvited and often unexpected guest in many phases of public and personal life. The memory of what some Germans did and many Germans chose not to notice remains an irritant, like an open wound that keeps hurting and does not heal. In the casual and sometimes serious conversations that happen during travelling, in which I was usually taken for a German and in which my purpose for being there usually remained unsaid, the past would often and sometimes quickly become the main subject, sometimes with an intensity that verged on compulsion, like an addiction that one fights against but in the end yields to – ever present, allowing no final conclusion, no resolution. I was not surprised that I recognized no consensus of what the Germans think should happen about the Nazi past; I found instead a clear division:

Many, perhaps most, Germans believe that there is a continuing obligation to remember what happened in the camps and the reasons why it happened and was allowed to happen, and who believe also that Germany has a continuing responsibility to try to prevent it from happening again.

But there are some Germans who think otherwise. The remains of the charred “Jews’ barracks” at the Sachsenhausen camp memorial site are one of many examples in Germany today in which a very different view of the past and a very different message for the future are unmistakably voiced. Expressed in the defacement and destruction of cemeteries and synagogues, in fires set to destroy the stores and homes of foreigners and intended to burn their inhabitants to death, it as a message that appears more than occasionally these days not only in such deeds but in the statements of some radical parties and in the speeches of some radical politicians. The words may vary but the meaning is always the same: you Jews and all you immigrants from eastern Europe or wherever else you have come from, you are not Germans, you are not welcome here. Go away and when you leave take with you the memory of what you say was done to you by Germans. We don’t believe most of it, but if anyone did it to you it was our grandparents, not we. We are tired of the mark of Cain that you have put on our foreheads, we have carried the burden of guilt long enough. Go away.

It is hard to foresee which of these messages – responsibility or denial – will prevail in Germany; the circumstances and elements that contribute to such decisions change constantly. It is not a German problem alone. Brutality and the destruction of “undesirables” for political ends have happened elsewhere since 1945 and are still happening – the earth is strewn with the evidence. The idea that was brought to a high state of the art of killing by the Nazis is alive and well and it has been improved upon since 1945.

Standing in the Auschwitz gas chamber I was confronted with the realities of deliberate and cold-blooded killing as never before. Not even during the war. It was an experience that I will not be able to forget, it was a reminder of what human beings were capable of doing to other human beings when passion and rage took the place of reason and basic decency. I realized again how easy it is in these days of high technology for the relatively few without conscience to take away the freedoms and spirit and lives of the many who are at their mercy. I came to understand that I was not safe – that no one anywhere is safe – form these dangers because the line that divides victors from victims – is thin and elastic.

If I had learned any lesson from having been in the remains of the camps it is that thinking or living for oneself alone has become an unaffordable luxury. Except perhaps in dreams, life no longer takes places on a solitary plane, it is now irrevocably complex, and we, whoever we are, have become intertwined one with the other whether we like it or not. Acting on that belief may be a more effective tribute to the memory of the dead than mourning alone of vowing that it shall not happen again, and it may also be the most promising way of doing away with the concentration camps. I am not an optimist , but I believe that if we decide that we must link our lives inextricably – that “me” and “them” must be replaced by “us” – we may manage to make a life in which gas chambers will not be used again anywhere and a future in which children, including my granddaughter, will not know what they are.

Erich Hartmann,

New York, September 1994