The Red Scare

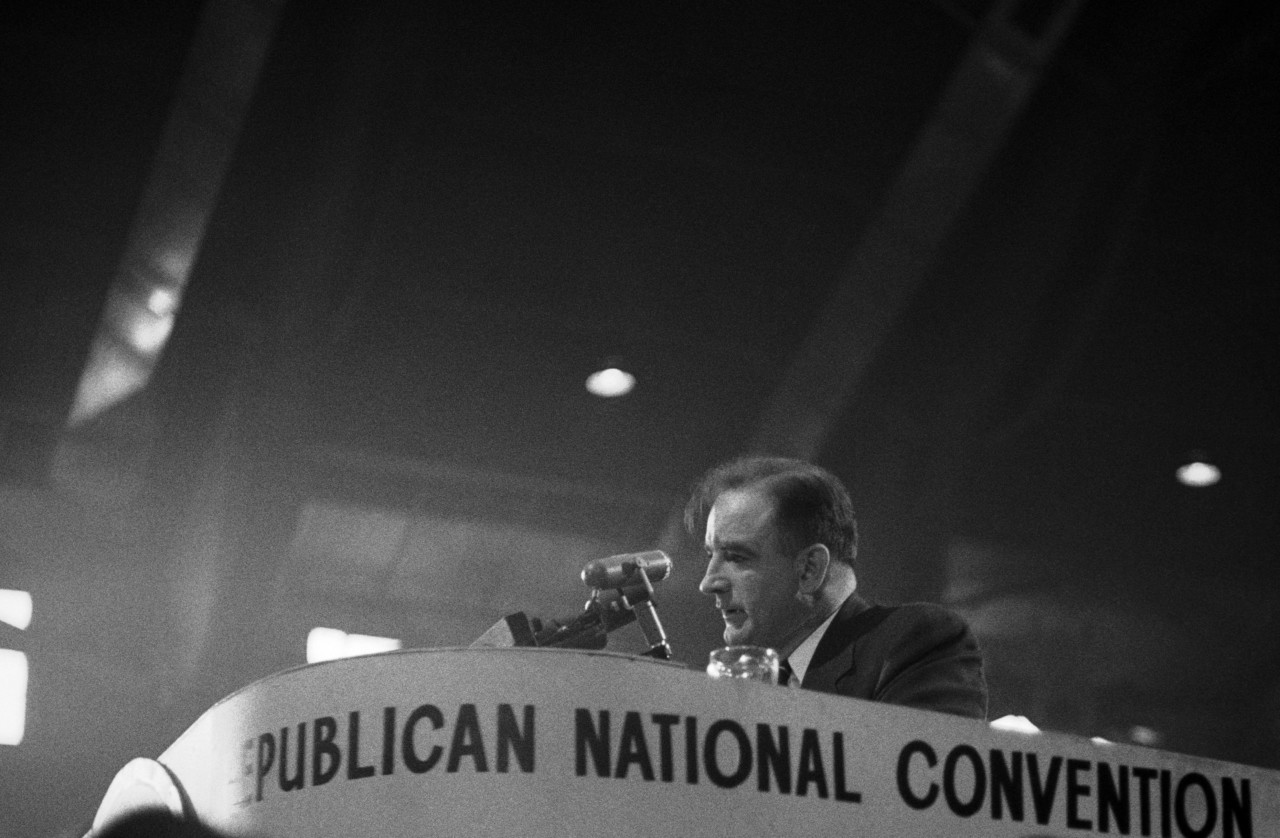

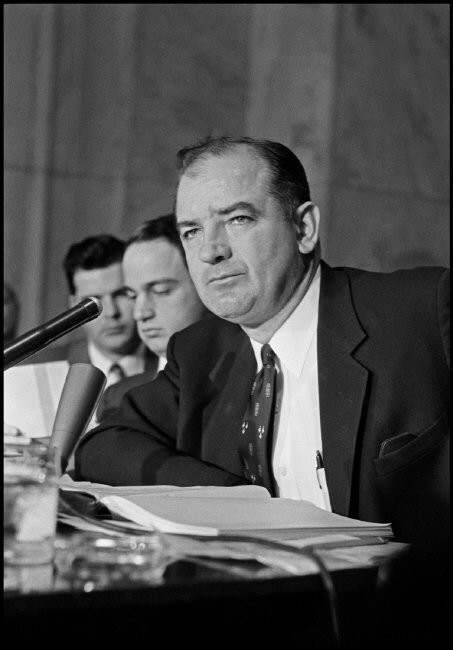

70 years ago, on February 9, Senator Joseph McCarthy made his infamous anti-communist speech, we explore how Magnum photographers captured the politician as well as the atmosphere he helped to instill in America during the 1950s

McCarthyism refers to a period of American history spanning 1950-1956, also known as the Second Red Scare, which immediately followed Senator Joseph McCarthy’s speech on February 9, 1950. In the speech, McCarthy brought the nation’s attention to what he believed to be a growing communist ideology amongst cultural and political figures in the United States. The Senator drew the nation’s attention to a piece of paper which he claimed contained a list of 205 individuals working in the State Department who were members of the Communist Party. McCarthy never produced the names of the officials he claimed were listed, nor any evidence of their membership.

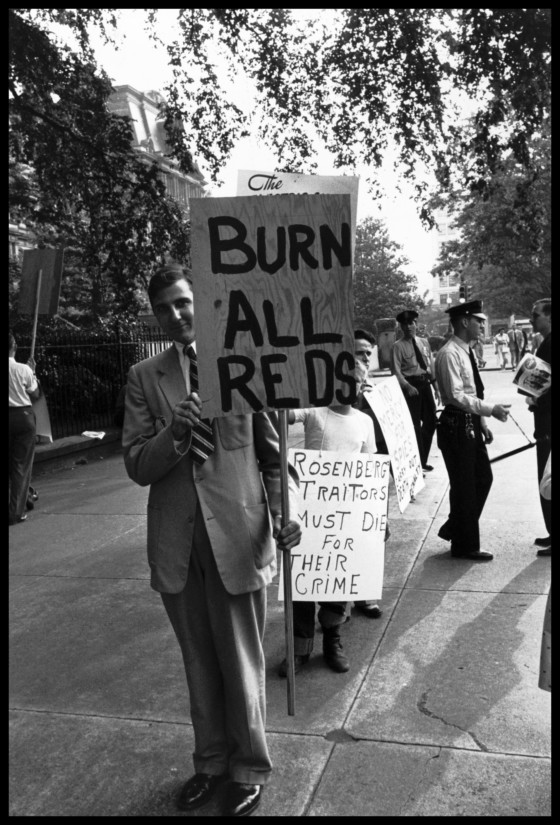

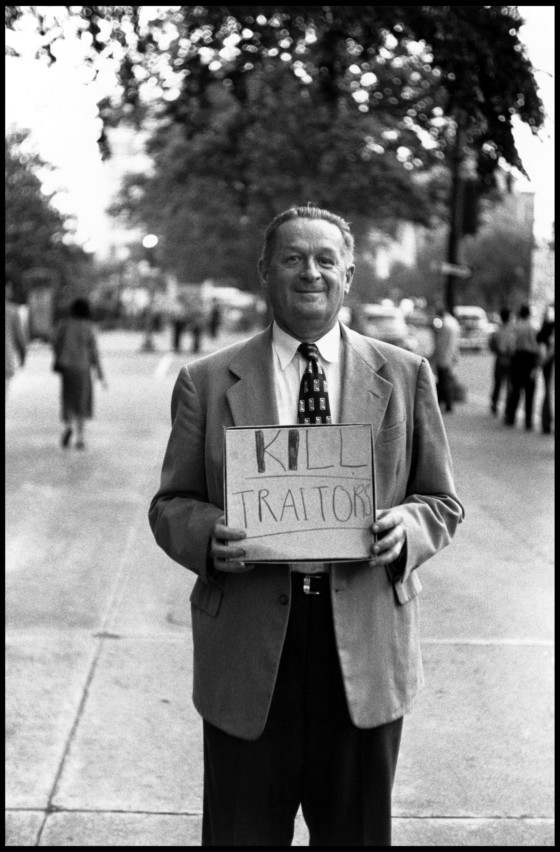

Persecution and blacklisting of individuals from professions including education, entertainment and the military occurred during the period of McCarthyism. The first high-profile case of this was the Rosenberg trial, beginning on March 6, 1951, captured by Elliott Erwitt, in which Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were accused of providing the Soviet Union with nuclear secrets in the lead-up to the detonation of the first Soviet nuclear bomb in 1949. The Rosenbergs, who denied accusations of collusion with the Russians, were sentenced to death.

Throughout this period the media faced widespread witch-hunts, with many influential figures in Hollywood made subject to televised hearings. The increased scrutiny also affected Magnum, as Eve Arnold details in her book, In Retrospect:

I chose to photograph Joe McCarthy, who in the fifties was holding America to ransom for his witch-hunt for Communists. When I came up with the idea, I spoke to Robert Capa about it. He was silent for a moment, then asked me if I minded waiting a bit before starting on the story: he said he had an important reason for asking me to wait—unfortunately, the reason would have to wait as well. He spoke to me a week later: he was leaving for Paris in a few days and would cable me from there. It all seemed mysterious and worrying, but the day he arrived in Paris he cabled thumbs-up so I could proceed. The reason, which I only heard years later, was that he was having trouble with American immigration authorities, who were threatening to lift his passport. As far as I can check, friends rallied to his aid, the situation changed, and he could step back from the shadow cast by McCarthy and okay my story. He had not wanted either Magnum or me involved in his troubles.

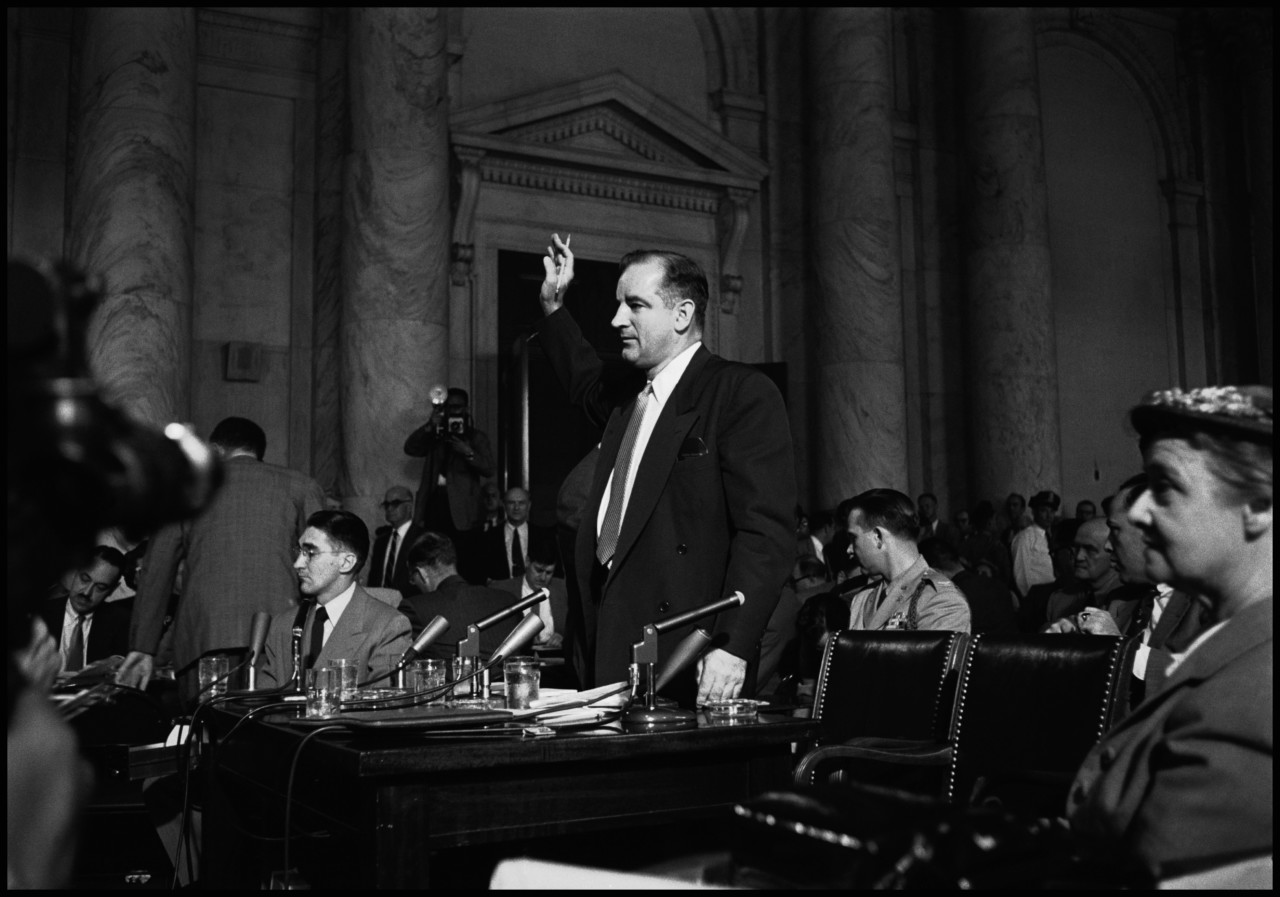

The end of McCarthy’s influence in office was marked by the Army-McCarthy hearings during 1954, photographed by Eve Arnold and Eric Hartmann, in which McCarthy was officially held accountable for corruption for the first time. Arnold, who described the politician as “exud[ing] an oily charm” detailed her encounter with McCarthy at the trial:

The senate hearing room where the McCarthy investigation was being held was a crazy circus complete with heavy press, television crews, batteries of lights and on a dais McCarthy flanked by his cohorts, Cohn and Schine, and various senators. Under the table where they sat were crouched two photographers, Speed Graphics at the ready, to pounce on the witnesses they faced. At noon when we broke for lunch Senator McCarthy held a press conference. He came over to me (I was the only woman there) and put his hand on my shoulder as he asked me whether I had any questions. I instantly put my hand up to remove his, but my brain telegraphed that this wasn’t a good idea, so we remained for beat, my hand covering his.

As gracefully as I could I managed to extricate myself by saying I had to get to work. Later when I went down to the Senate dining room to get a bowl of the famous bean soup, the thirty or so newsmen who sat at the same table ignored me, because they had witnessed the scene with the senator. Such was the climate of distrust that I didn’t dare tell them what had happened for fear of betrayal. Looking back now it’s hard to believe the climate of terror that existed in the fifties in America.

[…]

I found it very exciting to be doing political reportage, to be where history was being made, to be able to express what I felt about the injustice being practiced. The ugliness of it all was evident in the faces of McCarthy and his henchmen, and I tried to capture it on film.

Anti-Communist sentiment in film and media, in response to the perceived threat, was also prominent. The 1956 science-fiction film, Invasion of the Bodysnatchers, for example, told the story of citizens of a California town who are insidiously replaced by alien doppelgangers, a thinly-veiled political allegory for alleged left-wing subversion on the rise in America. Anti-communist feeling preceded the McCarthy era — tensions around the perceived threat of communism had begun after World War I, when the First Red Scare of 1919 to 1920 saw unwarranted searches and the arrests of thousands of suspected radicals following strike actions in Seattle and Boston. And whilst the sphere of McCarthy’s public influence ended officially with his censure in 1954, the sensationalism stirred up during those years is still evidenced in the culture and legacy of the years following.