Chernobyl: Survival in the Exclusion Zone

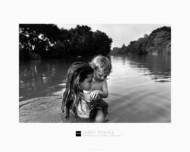

Larry Towell visited the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in 2017 to photograph longtime residents who refused to leave, as well as new arrivals drawn by cheap land and those fleeing conflict in Ukraine's east

On April 26, 1986, the Number 4 nuclear reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, near Pripyat in modern-day Ukraine, exploded as the result of a power surge during a systems test. The ensuing meltdown and fire resulted in the release of radioactive materials into the atmosphere, up to 30% of the plant’s 190 metric tons according to National Geographic, making for the worst nuclear accident in history. The event forced the relocation of hundreds of thousands of people from a 30km zone around the power plant, the Chernobyl Zone of Alienation, over the following weeks.

2017 saw Magnum photographer Larry Towell working in the regions of Ukraine surrounding the Chernobyl disaster zone, documenting and abandoned settlements and those still living in lands rendered radioactive by the 1986 disaster. These residents are made up of those who refused to leave their homes in the wake of the disaster, as well as more recent arrivals – persons displaced by conflict in the east and those lured by cheap real estate.

A selection of those images are shown here, alongside an extract from Kate Brown’s new book, Manual for Survival: A Guide to the Future, which examines the aftermath of the Chernobyl meltdown, and what the author describes as the “plot to cover up the truth”. Brown is a Professor of Science, Technology and Society at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), her focus is on the creation of “modernist wastelands” brought into being through combinations of bio-politics, history and science. The following extract deals with the experience of rural and agricultural workers in the region around the Chernobyl plant following the disaster. Many were pressed into action in the weeks, months, and years that followed the disaster – provided with post-fallout safety guidelines they were often ill-equipped, if not totally unable, to follow. Others continued to live and work unaware of the risks posed by their engrained means of existence.

Manual for Survival, by Kate Brown, is published by Allen Lane. Copyright © 2019 Kate Brown

"Much of the industrial age had passed this part of the world by, until it rained down all at once in the spring of 1986"

- Kate Brown

Modern disasters require a modern state to clean them up. The problem was that rural Ukraine and Belarus, where the greatest volume of fallout from the burning reactor landed, had few of the resources necessary for overcoming a high-tech disaster. Most villages within eighty kilometers of the plant lacked plumbing and central heating. The electrical wires that pulsed from the Chernobyl reactors missed many hamlets. Villagers carried water from open wells in open buckets. Taking a bath and doing laundry involved a lot of work and so occurred only occasionally. Heating came from burning contaminated peat and wood. Dirt roads generated dust carrying radioactive particles. The region was swampy. During spring floods, some villages were cut off for weeks or months.

Rural shops carried salt, kerosene, and matches but little else. Farmers ate what they produced on their private plots. Everyone worked the fields, including pregnant women and children. The few hospitals and clinics were understaffed. Much of the industrial age had passed this part of the world by, until it rained down all at once in the spring of 1986.

As regulations from Moscow stipulated that collective farmers become modern consumers of food, fuel, and medicine, while following safety regulations designed for workers at nuclear power plants, it became clear this would be a losing battle.

Half a million people resided after April 1986 in areas of Belarus and Ukraine with high and very high levels of radioactivity. Radiation levels in Belarusian villages surpassed those at nuclear reactors No. 1 and No. 2, restarted in the fall of 1986 at the sullied Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Measures to combat radioactivity telescoped onto the village—usually a cluster of two dozen to several hundred houses sur- rounded by vegetable patches, sheds, and small barns with an outer ring of fields. A village household doubled as a site of food production. Large kitchen gardens generated fruits and vegetables. Sheds held chickens, cows, goats, sheep, and pigs. Farmers hauled hay to store in their barns. They herded animals from pastures to stalls in the village. Residents gathered mushrooms, berries, and herbs, carrying them home. They cut wood from the forest and brought it to the village. They used ashes and manure, exceptional radioactive concentrates, for fertilizer. Trucks, horse carts, and buses tracked mud into the village. They washed the trucks and tractors, and radioactive puddles formed near garages. Flies that fed on manure swarmed into kitchens and onto food. A farm’s battle against flies took on new import after Chernobyl; so did dirt tracked home on boots. Day by day, radioactive isotopes were drawn into the village, the center of the rural economic vortex. Residents’ households became the spleen where radioactive isotopes moored. To deal with this exceptional circumstance, agronomists churned out survival manuals to teach farmers how to live and work in a postnuclear world.

"Radioactive fallout landed in the wells from above and seeped in from the groundwater"

- Kate Brown

Farm workers in areas with more than two curies per square kilometer were advised to dress like nuclear operators in jumpsuits, respirators, hats, gloves, and personal dosimeters. Farm bosses, who had neither dosimeters nor the training to use them, were told to somehow set up radiological control posts in every village. Farmers were to shower after work, could not lie down on the grass, eat outdoors, or ride in horse carts or in trucks with the windows rolled down. They could not burn branches or leaves, graze livestock in June and July, or use local wood or peat in stoves. They could not fertilize their gardens with manure and ashes or gather herbs, mushrooms, and wild berries in the forests.

Better not to even enter the forests, which were often the most heavily contaminated areas. To follow the survival manuals, in short, farmers were expected to give up the means of survival they had relied on for generations.

Soldiers and prisoners conscripted for dirty work dug up tainted topsoil and dumped it on the outskirts of villages in “temporary waste treatment areas,” which were just pits that were not lined, fenced, or posted as radioactive. To make up for lost nutrients in the topsoil that had been removed, agronomists told farmers to add more nitrogen fertilizers to the fields. Farmers poured on hundreds of thousands of tons of chemical nitrates. Agronomists noticed that in abandoned fields inside the evacuated zone pests that fed on unharvested produce proliferated “massively” after the accident. Collective farm managers sent workers into the Zone of Alienation to gather crops to stop the parasite explosion, while pilots from the farm-chemical service buzzed the fields, sending down a shower of pesticides, including DDT that had been formally banned. The volume of fertilizers and pesticides spread on radioactive land grew impressively in the post-accident years.

"As rainwater rolled off the roofs, radioactivity concentrated in the puddles pooling under downspouts"

- Kate Brown

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant was built on the southwestern edge of the great Pripyat Marshes, Europe’s largest swamp, in an area called Polesia. The surrounding terrain was marshy and boggy. Village wells in the region were shallow and open to the sky. Radioactive fallout landed in the wells from above and seeped in from the groundwater. Agronomists wrote more regulations, stipulating the need to dig deeper, artesian wells, cover them, and construct sewer systems for indoor plumbing. One of the first rules of nuclear emergencies involves simple hygiene. A contaminated person should wash up in the first hour or minutes after exposure. The longer radioactivity lingers on hair and skin, the more damage it does. Farm administrators wrote up plans to build village bathhouses and laundries for a new regime of “radiological hygiene.” It took years to build those bathhouses.

In the spring, ice dams clogged up the hundreds of rivers and streams of Polesia. In the floods, water spread horizontally across the marshy plains. In a healthy environment, seasonal floods are good. Inundating water spreads silt from river bottoms and refreshes soils with nutrients. Farmers staked their animals on the fertile floodplains where the grasses grew best. After 1986, spring floods became a problem because they liberated and spread radioactive isotopes that had settled in river bottoms. Hydrologists decided it would be better not to have any more seasonal floods, so they ordered crews to build dams lined with filters to channel water into dozens of holding ponds. In the summer of 1986, bulldozers rolled into contaminated territory to build new dams. Moving masses of earth for dam construction kicked up a lot of dust, which was picked up in the breeze, rode along on airstreams, and returned radioactive isotopes to communities that soldiers had just stripped of contaminated topsoil.

The conscripts fought the dust using a green, foamy chemical sprayed on houses, fences, tractors, barns, and schools. They pulled down thatch roofs and installed corrugated steel that insulated poorly but was easier to scrub with long iron brushes. As rainwater rolled off the roofs, radioactivity concentrated in the puddles pooling under downspouts. Engineers sketched plans to lay gas lines so villagers could heat and cook without radioactive wood and peat. Instruction manuals directed mayors to pave dirt roads, streets, and playgrounds, entombing the earth under asphalt.

The new plans called for farms to specialize in either meat or dairy production. They drew up schemes to monitor village food. They announced that villagers must give up their private livestock because villagers had no funds to purchase commercial feed. Leaders outlined budgets for village shops to receive “clean” food supplies. (Officials in Ukraine referred to “clean” food in quotation marks, expressing their understanding that all food had become at least a bit dirty.) This was a fast-tracked modernity. Polesians were told they should no longer grow their own food as they had for centuries through plague and war, drought and famine. In the postnuclear age, rural producers would become consumers. The only problem was that consumers are not made overnight.

Manual for Survival, by Kate Brown, is published by Allen Lane. Copyright © 2019 Kate Brown